Catie Cheshire

Audio By Carbonatix

In 2024 alone, Denver added 160 buildings to the city’s neglected and derelict building list, which documents properties that sit vacant and cause problems for neighbors.

Denver City Council has a new proposal to address the issue – as well as the risk of fires, squatters and debris across the city – so those buildings can be rehabilitated and put to better use, according to a handful of council aides.

“NADB properties are a significant burden on city resources and public health and safety from 911 calls, to 311 calls, to calls to council districts,” Ayn Tougaard Slavis, senior council aide for Councilwoman Jamie Torres, said in a June 10 city council committee meeting. “People are breaking into these properties, starting fires and attracting crime. The current ordinance has not been updated since 2012, which means our approach may not reflect our current needs and challenges.”

Currently, the city has to hold a formal hearing in order to fix the worst offenders of vacant properties, so a new legislative proposal suggests kicking the process off with a fast remedial plan between property owners and the city that would require boarding up neglected properties and taking steps toward activating those properties again.

To give the Department of Community Planning and Development more teeth, the legislative changes would also increase the amount CPD is allowed to levy in citations for neglected buildings from $999 to $5,000 per day.

City councilmembers have long struggled to come up with better ways for Denver to deal with problem properties, which peaked last fall when Councilwoman Amanda Sawyer talked about a problem property “doom loop,”

including a vacant church on Colorado Boulevard that required 165 service calls and the involvement of 260 city personnel before it was demolished.

Other vacant properties around Denver that caught attention include a fourplex that exploded on Lincoln Street and took nearly a year to be demolished and a home owned by Habitat for Humanity that has caused thousands of dollars in property damage to the home next door, according to that homeowner.

Because so many agencies can be involved, there still isn’t a clear path for neglected buildings to be fixed. The proposed legislative changes aim to both make sure CPD has the resources and tools the department needs to enforce the city’s laws and provide a clearer path forward for neglected properties.

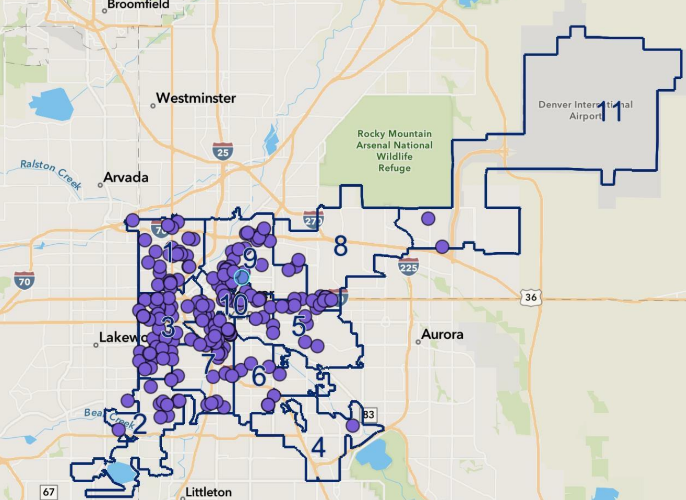

As of April 2025, there were 285 properties on the NADB list. The list is mostly made up of single-family homes, but commercial properties and forty historic properties are also on the list. Every city council district currently has properties on the list, but the top districts are District 3 in west Denver and District 9, which covers parts of downtown Denver, the River North Arts District and City Park. Then comes District 3, which runs along Interstate 25 from 6th Avenue to Ruby Hill, and District 1 in northwest Denver.

A map of neglected buildings in Denver, June 2025.

City of Denver

“I can’t imagine any council person doesn’t get a call or a complaint about an abandoned or neglected property in your district,” Torres said at the June 10 meeting. “We can spend a lot of resources sending our police officers out to do welfare checks, sending the fire department out to do responses to fires that might exist in some of those abandoned buildings.”

The proposed changes were thought up by Tougaard Slavis, Councilman Paul Kashmann’s senior aide, Masha Lior, and Sawyer’s senior aide, Owen Brigner. The three hope to cut down resources the city spends on emergency response to neglected properties by allowing CPD to issue fines if fire, police or EMS services respond to a neglected building more than three times in six months. That penalty could cost up to $5,000, with fines going to the city’s general fund as they currently do.

Under the proposed changes, once CPD designates a building as neglected and derelict, the property owner has sixty days to meet with CPD to create a remedial plan. Right now, the parties must attend a show cause hearing to reach any sort of plan, which council aides find extremely inefficient.

“There won’t be a show cause hearing in this new proposed ordinance,” Bringer said. “Show cause hearings really bogged down the process and extended that timeline. By doing that remedial plan assessment meeting at the beginning, we’re going to, hopefully, be able to bring these properties into compliance much quicker.”

Council aides also stressed that the remedial plan meeting would improve equity in ordinance enforcement: Some properties are owned by bad actors taking advantage of Denver’s lack of enforcement tools, while others are owned by people struggling to afford upkeep or circumstances like incarceration or disability that make home upkeep difficult. A remedial plan meeting would allow the city to consider those factors, according to the proposal.

If a property owner does not meet with the city within sixty days, CPD would be allowed to begin citing the property.

Should a property owner ignore those citations or fail to pay fines within thirty days, the new ordinance would let the city petition Denver District Court to issue preliminary injunctions against property owners from continued violations. If that injunction is ignored and the owner still fails to pay fines, the city can seek court-ordered abatement or appoint a receiver to control and remediate the property.

The exploded property at 457-461 South Lincoln Street was one of over 120 derelict buildings in Denver last June, according to the Department of Community Planning and Development

Catie Cheshire

If successful, CPD could also initiate emergency abatements to put up fencing and establish security measures, like “no trespassing” signs and boarding up homes. If CPD took that action, the department would have to notify the property owner within 48 hours; the department could then require the property owner to reimburse the city for the costs of the abatement.

The ordinance also tackles neglected historic properties, which would have the same process as other properties but CPD would need to notify the Landmark Preservation Commission before any emergency abatement to ensure the work doesn’t interfere with the historic nature of the property.

Under the ordinance, vacant lots would also be included on the registry as CPD has found that after buildings are demolished, vacant land can cause similar problems to neglected buildings. However, the city code isn’t designed to include vacant lots without buildings in the NADB process right now. Lots could be designated as neglected and derelict if they are not maintained, if the property has been vandalized or subject to other destructive activity, or if the property is within 1,000 feet of a school, park or recreation center.

Finally, the ordinance would require a report from CPD to the council each March to increase transparency, inform budget decisions and figure out which other city departments may need more support to help with vacant buildings.

Four members of the public spoke in favor of the idea at the June 10 meeting. None spoke in opposition.

Council aides noted the city’s pending budget deficit could come into play as the changes will likely require CPD to hire more employees and spend some money on internal infrastructure updates. Though the aides said the new fee structure could make up for some of those costs, that is not guaranteed.

The proposed ordinance could take effect in February 2026 if successful, but aides said their councilmembers are open to amending the start date if the city budget can’t accommodate the updates. Councilmembers seemed to indicate they want to pass the ordinance regardless.

“For me, I think it’s essential we move forward with this,” Kashmann said. “People who drive on our roadways don’t always pay attention to the speed limits, and we don’t have police everywhere to enforce that, but we don’t decide, ‘Well, let’s get rid of the ordinance.’ The ordinance is in place because when we do need to enforce it, we’re able to do so.”

The changes passed unanimously out of committee and will be heard by the full council for the first time on June 30.