Patricia Calhoun

Audio By Carbonatix

Almost a year after the Broomfield City Council voted to cut its ties with the Jefferson Parkway, Broomfield is still negotiating with Arvada and Jefferson County on how it can withdraw from the project – and those entities are asking Broomfield for millions of dollars, as well as the right to go ahead and build the parkway through Broomfield.

Back in 2008, Broomfield joined with Arvada and Jefferson County to plan the Jefferson Parkway toll road, working together to create the Jefferson Parkway Public Highway Authority (JPPHA). The parkway is designed to connect state highways 93 and 128, nearly completing the Denver beltway that already surrounds much of the metro area. But the proposed route runs adjacent to the site of the former Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant – which was shut down in 1989 after the FBI raided the facility to investigate allegations of environmental crimes there – and it has drawn a good deal of criticism from residents, even though much of the onetime plutonium-processing plant is now a national wildlife refuge and state officials have said the route is safe.

Broomfield councilmembers cited public-safety worries, along with a handful of other concerns, including the project’s economic viability, when they unanimously voted to withdraw from the parkway in February 2020. By then, Broomfield had devoted about a dozen years and millions of dollars to the effort. But over the years, councilmembers said, they had seen many warning signs, and despite their efforts to get the parkway rerouted away from Rocky Flats, other planners from Arvada and Jefferson County consistently outvoted them.

The Broomfield move came less than a month before the COVID-19 pandemic hit Colorado, and as the state’s stay-at-home order went into effect, discussion of the terms of Broomfield’s withdrawal were repeatedly postponed. Those negotiations picked up again toward the end of 2020 – and according to Broomfield Mayor Pat Quinn, the other governments in the JPPHA have asked Broomfield to guarantee the dedicated right-of-way so that the parkway path can continue as planned, crossing Broomfield.

Arvada and Jefferson County have also asked Broomfield to pay millions in financial reimbursement and the total cost of a 2019 soil study, according to an October 13 letter sent by Broomfield’s attorney to Arvada and Jefferson County’s attorneys. Additionally, Arvada and Jefferson County have asked Broomfield to agree to a “statement of neutrality” – which the Broomfield attorney’s letter describes as “a gag order about any concerns its elected representatives may have about transportation, public health, safety or environmental concerns associated with the Jefferson Parkway.”

JPPHA

JPPHA Executive Director Bill Ray referred all questions about the negotiations to Arvada, Broomfield and Jefferson County. Arvada Mayor Marc Williams declined to comment because negotiations are ongoing. A Jefferson County spokesperson said the county could not provide information on the parkway at this time because Jeffco’s new board of county commissioners has not yet reviewed all of the project’s details.

In its letter, Broomfield addressed each of the requests from Arvada and Jefferson County. According to Broomfield, the contracts between the three governments do not require Broomfield to reserve the right-of-way for the parkway.

Broomfield also argues that it should pay only a portion of the soil study costs instead of the entire bill because it had previously agreed to split the expense with the other governments. That soil study was undertaken in May 2019 to test how much plutonium remained in the soil in the eastern portion of Rocky Flats, near the proposed parkway route. The study was prompted when members of the public voiced concerns that, even after the cleanup of the Rocky Flats site completed in the mid-2000s, some plutonium remained in the ground and could be stirred up during parkway construction, putting nearby residents at a greater risk of developing cancer.

In reviewing the results of the independent study, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment said that parkway construction would not pose a risk for construction workers or neighbors. While the study had found trace amounts of plutonium, they were within established safety limits, according to the CDPHE. And although one anomalous sample first tested at unsafe levels, a second test put it within safety limits, the CDPHE said.

Broomfield is also arguing that it “does not owe further participation fees” – $2,500,000 that the JPPHA had asked for in 2019 and never received from the city. “While the JPPHA budgeted $2,500,000.00 contributions from each of its members for 2019, Broomfield’s City Council never approved expenditure of those funds,” the Broomfield letter states. “Both the Establishing Agreement and the Reimbursement Agreement recognize that each of the member governments must follow its laws for budgeting, appropriating and expending money before there is a binding obligation of the member government. That is the law of Colorado in any case.”

Finally, Broomfield declined to agree to a statement of neutrality, and said it wanted to discuss contractual reimbursement from the JPPHA.

Broomfield has requested a meeting with Arvada and Jefferson County to discuss its withdrawal from the parkway plan, but that meeting has yet to occur.

“It’s been tough to do in the last six months, to sit down at any table with anybody,” Quinn notes. “We’ve made an offer of withdrawal, and they responded back with a number that wasn’t designed to bring us to the table. They came up with a number designed to fight. Broomfield’s not exactly certain what to do; I can’t imagine our city council is going to give the right-of-way. If they want to take legal action against us, I guess they can.”

Not that Broomfield is eager to litigate, however. “We’re more than willing to sit at a table and discuss with them reasonable terms of withdrawal,” Quinn adds. “We want to work with them.”

In the meantime, nearby cities have been keeping a close eye on the stalled parkway plans and weighing how Broomfield’s withdrawal might impact them. Back in 2012, both Golden and Superior sued to stop the transfer of some Rocky Flats land to the parkway. Since their lawsuits were dismissed, both cities have been preparing for the arrival of the parkway. Golden’s preparations have included working with highway planners to create the Golden Plan, which altered the parkway path to mitigate noise for Golden residents and add interchanges that would keep the parkway from cutting off part of the city.

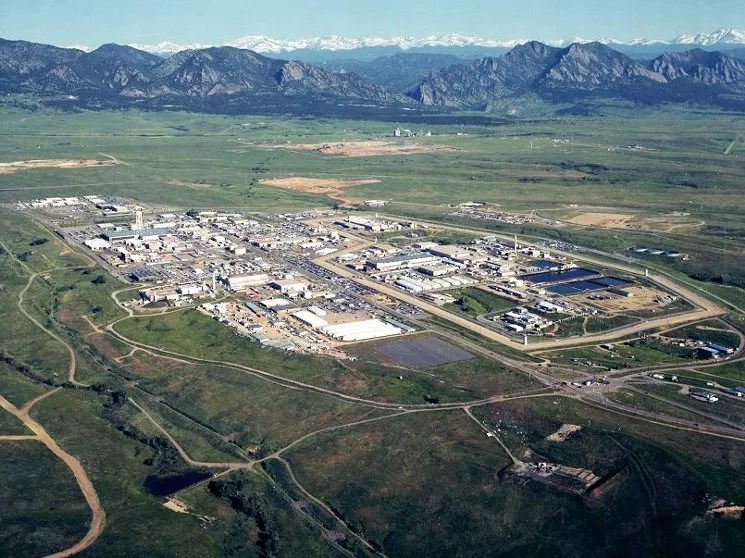

The Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant three decades ago.

Department of Energy

Because of that plan and the soil study – and because multiple models have suggested that the parkway will not attract a significant percentage of traffic to the area – Golden will be content whether the parkway is built or not, says Dan Hartman, the city’s director of public works. “If it does get built, it won’t generate any traffic,” he notes. “The Authority has done some testing, and they don’t believe the construction there would trip any standards.”

Superior, which is much closer to the proposed route, is still adamantly opposed to the parkway, according to Mayor Pro Tem Mark Lacis. “Rocky Flats remains contaminated with plutonium. There’s no dispute about that,” Lacis says. “From my perspective, it is not safe.” And not only does the town oppose the parkway; it’s also opposing another plan for the Rocky Flats site, the Rocky Mountain Greenway trail project.

For Superior, Broomfield’s withdrawal from the JPPHA came as welcome news – and Lacis says he still has high hopes that it could ultimately mean the parkway’s end.

“Broomfield’s not going to be financially contributing to the project, and without Broomfield’s participation in that program, it’s going to be that much harder for Jefferson County and for Arvada,” he explains. “My hope is that without Broomfield’s participation, the highway project is going to be dead, and we’re not going to have the threat of a highway.”

And even though Golden is now out of this fight, it’s not optimistic about the parkway’s future. Says Hartman, “We think it is totally unneeded and it will be a colossal failure.”