Jay Vollmar

Audio By Carbonatix

Real estate is on fire all over metro Denver, but there’s a particularly hot property in Westminster. The Pillar of Fire Church owns hundreds of acres, including a large working farm between Federal and Lowell boulevards and 84th and 88th avenues.

But now the church, which has its own fiery history, wants to sell off much of the property, including the farm – one of the rare stretches of undeveloped land in the area.

The proposed deal has become the focus of heated discussion in this northern suburb.

Local development company Oread Capital and Development plans to purchase the farm and a few adjacent properties from the church and develop a new section of Westminster that would house thousands of future residents in a project it’s calling Uplands. That has members of Save the Farm, a citizen advocacy organization, up in arms, and they’ve let Westminster City Council know that there could be hell to pay if it votes for this proposal.

Westminster Castle is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Evan Sem

In the late 1800s, Presbyterian ministers came up with the idea of establishing a “Princeton of the West” in the Denver area. Henry J. Mayham, a native of New York who’d moved to Colorado, realized that land he owned between Denver and Boulder might increase in value if a Presbyterian university was set up nearby, so he donated 640 acres of land to the Denver Presbytery.

Forty acres of that donation would be used for the campus of Westminster University, eighty acres for a farm to support and feed the school, and the rest divided up and sold for the predicted community that would develop around the project.

“The Presbyterians wanted to make the university comparable to Westminster in England,” says George Smith, a researcher with the Westminster Historical Society. So while the pedigree that the school’s founders were going for was Ivy League, the architecture was regal.

Architect E.B. Gregory designed plans for the main building, and construction began in 1891. But funds were scarce during those early years, and the Panic of 1893 led to many delays.

Years later, Mayham asked friend Stanford White, an architect and fellow New Yorker, to redesign the university’s primary building. White came up with a three-story structure built from red sandstone quarried in Colorado. This would become Westminster Castle.

Finally, the school was incorporated as Westminster University of Colorado, and classes began at the campus in September 1908.

In 1911, the community in which the school was located, Harris, changed its name to Westminster in honor of the university, according to the Uplands project website.

The school’s farm was developed during this time and helped feed students and faculty at the university, according to Linda Graybeal, president of the Westminster Historical Society. “The wheat was not sold,” says Graybeal, who currently teaches at the school’s successor and has served as a historical advisor for the Uplands project.

But then, in a move that couldn’t have been more poorly timed, the board of trustees opted to change the school from a coed institution to an all-male university. Soon most of the students left to serve in World War I, and Westminster University closed.

Alma White started both a church and a radio station in Denver.

Wikimedia Commons

In 1920, the Pillar of Fire Church bought the property. Alma White, an outspoken feminist, had founded the Methodist church at the turn of the century, putting its headquarters in New Jersey. She and her husband, Kent, set up a radio station there; they did the same in metro Denver in the ’20s. They also established an elementary school, high school, junior college and Bible seminary on the Westminster property. In 1925, the church changed the name of the campus from Westminster University to the Belleview College and Preparatory School.

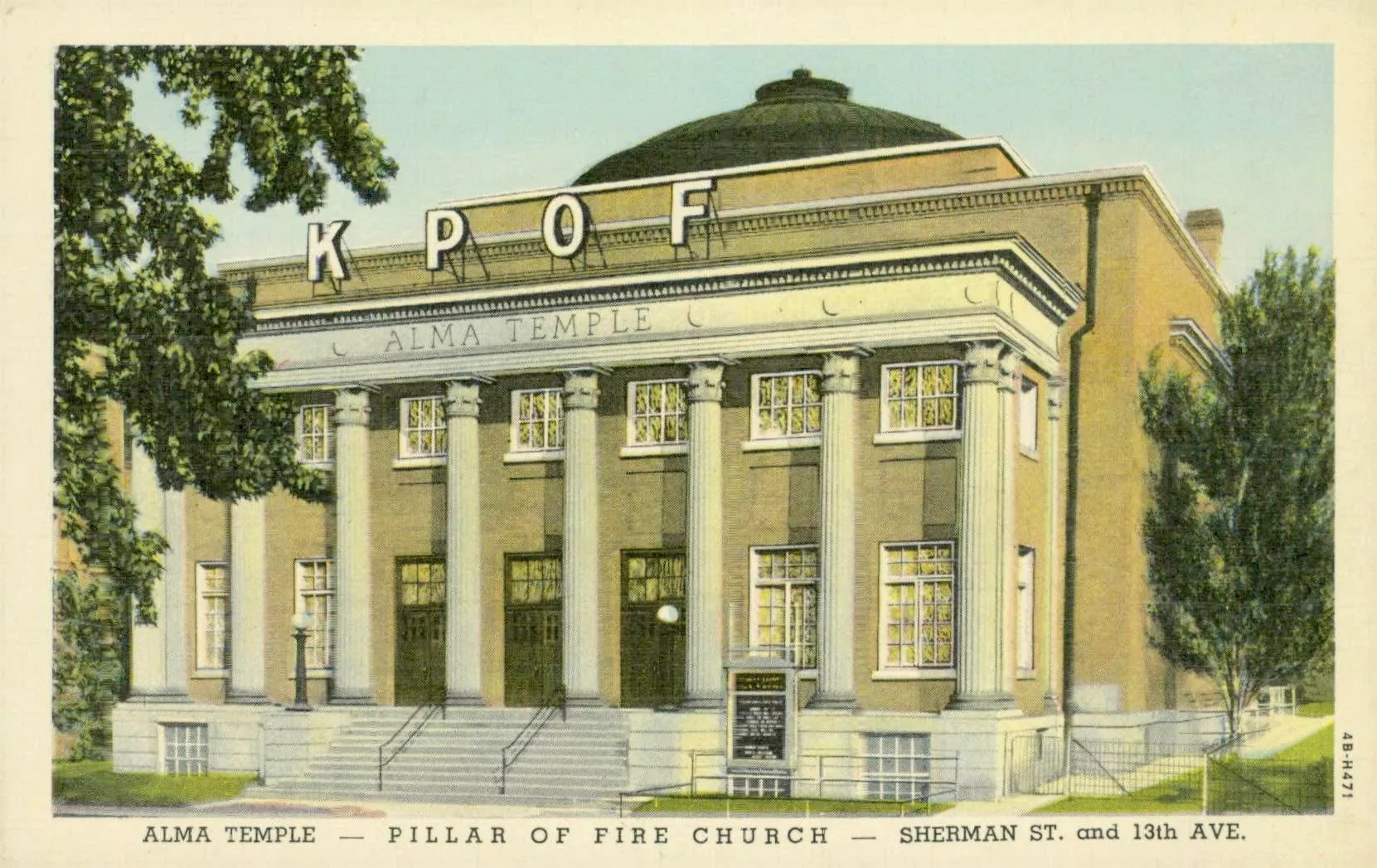

“Part of the reason why she came here was because the eastern United States churches would not allow women clergymen, and there was nothing here,” explains Smith. “Back when the Pillar of Fire moved here, there was a well up here at the castle, and everything else was only ditches and canals. White also set up a Pillar of Fire church on Sherman Street just south of the Capitol, now the Alma Temple.”

Aside from being a vocal proponent of women’s rights, White also happened to be a strong supporter of the Ku Klux Klan, which was especially powerful in Colorado in those days. She was particularly disdainful of Catholics, and combined that hate with Prohibitionist stances.

“She believed that drink and the Catholic Church were basically enslaving and chaining women,” says Bob Goldberg, a University of Utah professor who wrote the book Hooded Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Colorado.

White allowed the Klan to burn crosses on the church’s property and to hold a statewide convention there in 1927. The Pillar of Fire Church would not renounce its association with the Klan for another seventy years.

In the meantime, Westminster kept growing. It had a population of just 235 when White came to town; by 1950, it had 1,686 residents. In the decades that followed, the population mushroomed, hitting over 50,000 by 1980 – thanks in large part to a better water-supply connection. Today the population is closer to 115,000. Through all of that growth, the Pillar of Fire property has been home to a working farm, now up to 150 acres.

Over the past half-century, Curt Alstadt has been in charge of the farm. His grandmother and grandfather were missionaries with the Pillar of Fire Church.

“I personally started farming it when I was seven,” Alstadt told Westminster City Council during a meeting in early 2020. He described the farm operations, including how he grew crops to feed the church’s dairy cows in the 1960s and 1970s. “It became a challenging situation as other farmers and land started selling and being developed. We’re talking at the end of the ’70s,” he added.

The church ended up selling the dairy portion of the farm. “After that, our crops were sold for our ministries, whether it’s the schools, church or the radio station,” Alstadt said.

Alstadt also appeared before the Westminster Planning Commission to talk about the farm. “It is difficult for some years to even make a profit,” he said, noting that his own daughters weren’t interested in taking over farming duties in the future.

Over the years, the church has sold not just the dairy, but other parcels, as well. Today it owns about 330 acres in Westminster and adjacent unincorporated Adams County.

The Alma Temple is still open today on Sherman Street.

Wikimedia Commons

The Pillar of Fire Church still operates Christian radio station KPOF out of Westminster. It also continues to run the Belleview Christian School, now K-12, on the property, where Westminster Castle has been added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Pillar of Fire representatives declined to talk about the proposed sale because the church is under contract with the developer.

“It has been declining in both mission facilities and other facilities across the nation. It’s been declining in enrollment of staff and teachers. People keep getting old and dying,” Graybeal says. “Their source of income has always been limited…which led to ‘Let’s sell off some land.'”

In 2007, a developer started coveting the Pillar of Fire Church’s land. The City of Westminster’s planning office approved a proposal from the developer, but the project never went ahead.

“The Great Recession of 2008 was really hard on this development,” explains Ryan Hegreness, a City of Westminster spokesperson. “Planning’s recollection is that this was one of the first to fail.”

But Westminster, like the rest of metro Denver, came back after that recession, and with continued population growth, “housing is a challenge across the spectrum,” explains Aric Otzelberger, operations and community preservation manager for the city’s Department of Community Development. “We have roughly a thousand acres that could be developed, not including our open space. Almost a quarter of it is here, under a singular private ownership. There’s always a desire to create a unique sense of place, to create a community.”

“We have roughly a thousand acres that could be developed, not including our open space.”

In 2013, the City of Westminster formally stated what it would like to see on the church’s undeveloped land in the 2040 Comprehensive Plan, designed as a road map for the future. The plan designated the farm as the potential site for a “traditional mixed use neighborhood development,” or TMUND, “with a mix of residential and supportive non-residential uses in a walkable, pedestrian-oriented, urban village development pattern.”

Housing in a TMUND could include medium and small-lot single-family homes and multi-family apartments and lofts, among other options; there could also be offices, businesses and retail. “An interconnected grid of streets, pedestrian connections and parks is emphasized,” the plan noted, pointing to Bradburn Village as an example of a successful TMUND project.

Bradburn Village, located near West 120th Avenue in Westminster, is a mixed-use planned neighborhood that developers began building at the turn of the millennium. The development features over “750 residential units including townhomes, live/work units and row house apartments, all within a short walk of Bradburn’s village core, with 100,000 square feet of shops, restaurants, offices and a newly opened Whole Foods Market,” according to the website of Continuum Partners, one of the companies that developed the area. “The homes in Bradburn realize significant premiums over the more conventional subdivisions in the surrounding area. The efficient use of land, including a village green, parks, formal gardens, playgrounds, sports fields, event center and even an apple orchard, are other features of the community, making Bradburn Village a perfect model for smart growth.”

Westminster City Council signed off on the 2040 Comprehensive Plan in 2013, the same year that Oread Capital and Development began looking at potential development opportunities in Westminster. It focused on the Pillar of Fire Church property.

Jeff Handlin envisions a new community for thousands in Westminster.

Evan Sem

“Everybody knew this piece of land was going to be developed. The owner was not shy. The city was not shy,” says Jeff Handlin, founder of Oread Capital, pointing to the comprehensive plan as the guiding document showing the city’s intent to have the property developed. “An awful lot of people need homes, an awful lot of people need jobs. And this land can provide both.”

In 2019, Oread Capital went public with its plans to purchase land from Pillar of Fire. The company wants to acquire 233 acres, including the farm. The church would retain around 100 acres, including the property that is home to the school and Westminster Castle.

As currently envisioned by Oread Capital, the Uplands project would have 2,350 small- to mid-sized dwelling units over those 233 acres, with an estimated population of over 5,000. The residences would be a mix of single-family homes, both detached and in the paired-home and townhome styles, in addition to condos and apartments. “Single family homes will be built on smaller, more water-efficient lots with front porches that encourage community interaction and a friendly, walkable neighborhood,” according to Uplands’ website.

Karen Ray, an IT professional who lives in neighboring Shaw Heights, in unincorporated Adams County, wasn’t feeling very friendly when she caught wind of the proposal in late spring of 2019. She and other neighbors concerned about the scope of the project organized a meeting that August at the library.

“It was out of that that Save the Farm was formed,” recalls Ray, the organization’s leader.

The group has been vocal in its opposition to the project online and in person, organizing such events as picket lines around the farm. It also spoke out against the project before Westminster City Council in early 2020. when the council approved some changes to the comprehensive plan, including new zoning allowances for three of the five parcels in the Uplands proposal.

Save the Farm lists a handful of reasons why Westminster City Council should vote against the proposal in the future: protecting open space, preventing urban heat islands, pushing back against environmental racism, and saving gorgeous views of the mountains and the Denver skyline.

“It really is a jewel in the northwest Denver area. It’s such a special and unique place.”

“It really is a jewel in the northwest Denver area,” says Ray. “It’s such a special and unique place.”

Ray, who moved to the area for work in 2008, lives with her partner about four blocks from the farm. “We have one park in Shaw Heights, which is really nothing more than a sound barrier. It’s half an acre, and it’s got a rusted picnic table and a garbage can in it,” she says. Most of the members of Save the Farm come from Shaw Heights and nearby areas; although the Facebook group lists 850 members, only a few dozen are actively involved in Save the Farm advocacy efforts. But that’s enough, according to Ray.

“The community group that has come together, it’s such an awesome community,” she says. “It’s so rich culturally. A large Latino community, large Asian community. And a lot of people who have been here since these houses have gone up. It’s very working-class. There’s no McMansions or HOAs down here. It’s just a really down-to-earth community.”

Ray and other members of that community want the farm to stay as it is. If the church must sell it, they think that the City of Westminster should buy the land and preserve it as open space, either in the form of parks or just grassland. If the city doesn’t have the cash to afford the land, Ray suggests it apply for funding from the Great American Outdoors Act in order to save some of the great outdoors.

“Once it’s gone, that’s it,” she says. “You don’t get it back. You can’t say, ‘Oh, kidding, we didn’t mean that.’ It’s gone. You’ve destroyed something magnificent where generations have been able to go for a sunset and just breathe in a little bit of nature, a little bit of mental health, as well as physical well-being.”

John Palmer has lived across from the farm on Lowell Boulevard his entire life. He expects his home value to drop dramatically if the development plan is approved, and also worries about living next to nonstop construction for years.

“It’ll be an emotional hardship, says Palmer, who’s a member of Save the Farm. “It’ll be a health hardship with the diesels, the noise, the dirt blowing.”

Save the Farm doesn’t see Handlin leaving any room for compromise. “From the beginning, he’s gone the other direction,” says Karl Merida, another member of Save the Farm. “Why would you give an inch to someone who’s trying to squeeze every [inch]?”

Karen Ray has been leading the fight against the Uplands development.

Evan Sem

Although the farm is not open to the public, neighbors say they’ve been allowed to walk across it for years.

That’s the exception, not the norm, according to Handlin: “It’s open, but it’s not open space. It’s actually not publicly accessible.”

His project would make some of the property public, he says, setting aside 34 acres for the City of Westminster to develop as parks, and another six acres for the city to preserve view corridors. “This area will not have a park deficiency. It will no longer be classified that way,” Handlin says.

But Ray doesn’t buy that. “They’re not going to give one blade of grass more than they actually have to,” she says. “We think that the community and future generations deserve more than what is being proposed by the developer.”

Ray points out that the Westminster Municipal Code requires that a new residential development dedicate twelve acres of public land for every 1,000 people. Handlin’s company recently projected that the population of Uplands would be 5,149, which would result in a public land dedication requirement of over sixty acres.

According to Westminster spokesperson Hegreness, if the city determines that the amount of required public land “would not serve the public interest,” the city can permit a combination of a smaller amount of dedicated public land and “payment of a fee in lieu of the portion of land not dedicated.”

Given the size of the project, paying a fee shouldn’t be a problem. “We’re doing $90 million of construction per year for fifteen years,” notes Handlin. “That’s $1.4 billion of construction spending happening here.” Oread Capital wouldn’t handle the construction itself, but instead sell sections of the parcels to other home builders.

But Handlin would stay involved in other ways. Oread Capital has already created a nonprofit, Uplands Community Collective, to focus on food and agriculture projects, workforce development, business development and civic engagement.

“I would love to see a ten-acre working farm that is feeding the community and addressing food insecurity in that area and providing a community connection point to bring people together,” says Eric Kornacki, who’s heading up the Uplands Community Collective.

“I would love to see a ten-acre working farm that is feeding the community and addressing food insecurity.”

Others see additional benefits to the project. “We are way short of housing,” says Susan Daggett, executive director of the Rocky Mountain Land Use Institute at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law. “Over the last fifteen years, we’ve built a lot of single-family housing that doesn’t actually meet the needs of the population we have. We’re the third-least-affordable state in the nation when you compare our median incomes with our median home sale prices.”

While those statistics may not satisfy neighbors of a proposed project, they’re hard for city officials to dispute.

“We can argue about whether growth is good or bad, but as long as we have a strong economy, we’re going to attract workers, and we have to house them,” explains Daggett. “There’s like a million arguments with the problem with growth, but we can’t build a border around ourselves. We’re not an independent country. We can’t decide who gets to move here.”

The area doesn’t just need more housing, officials say. It needs housing that meets specific needs.

Oread Capital has already come to an agreement with two builders that together will construct over 300 units of “income-restricted and senior affordable rental housing at 30 to 80 percent of the area median income,” according to the website. The Uplands project will also feature over 180 “for-sale detached cottages” that range in size from 800 to 1,400 square feet and are targeted to “meet the Adams County definition for attainable workforce housing.”

The full development of the property will take around fifteen to twenty years, Handlin estimates.

But first, he needs Westminster City Council to approve his development plan.

City planning officials have been going back and forth with Oread over proposal documents, owing to the “city’s desire for additional detail,” explains Community Development’s Otzelberger.

If all those details are provided, the Westminster Planning Commission could hold a hearing on the proposal sometime this summer. It would then offer a recommendation to Westminster City Council, which could vote on the proposal as soon as this fall.

Approval is no sure bet.

Politics in Westminster are very heated these days. Another citizen advocacy group, Westminster Water Warriors, has been railing against elected officials over high water rates; the group collected enough valid signatures to force recall elections of Councilman Jon Voelz and Mayor Herb Atchison. The mayor recently resigned; the recall vote on Voelz is pending.

Ray believes careers could also be riding on the Uplands proposal.

“If they vote on this and they approve it, careers will be over for some of these city council people, that I promise you,” she says. “That will not be swallowed well by the residents here.”

But if council doesn’t approve the project, the city could be looking at a lawsuit. “The community absolutely has the right to say no, but they have to pay for it if they do,” says Daggett.

After all, Otzelberger points out, this isn’t Soviet-era Russia, where the government can dictate all land use and deny the rights of a property owner – even if it’s a church.

“In this country,” he says, “private property rights are a very sacred thing.”