Colorado Geological Survey

Audio By Carbonatix

It’s an El Niño winter – when weak trade winds in the Pacific Ocean make the northern United States drier and the Southeastern ones wetter. But what does that mean for Colorado?

This weekend, it means avalanches – including one that hit Berthoud Pass on January 14, and will keep it closed overnight.

Berthoud Pass on January 14.

Colorado Department of Transportation

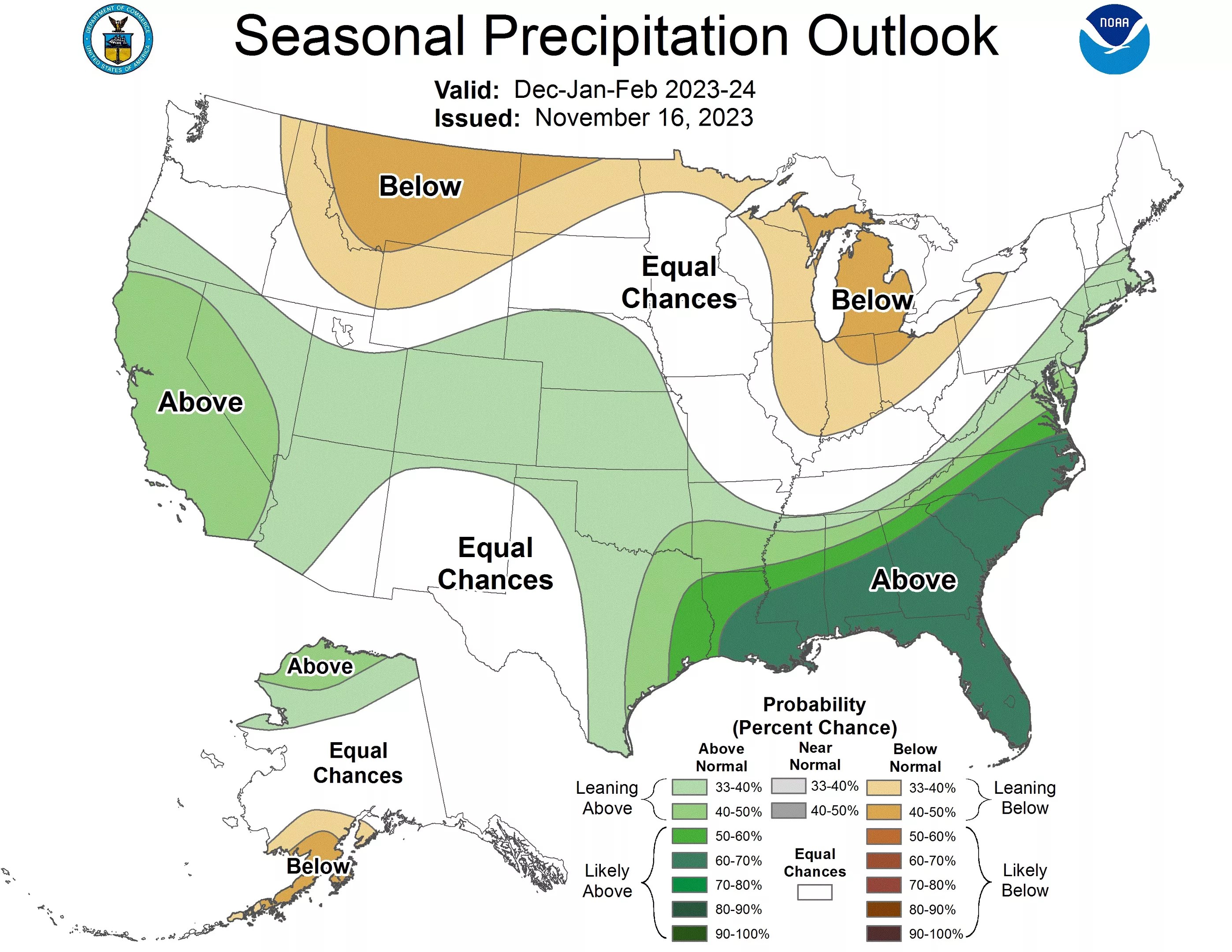

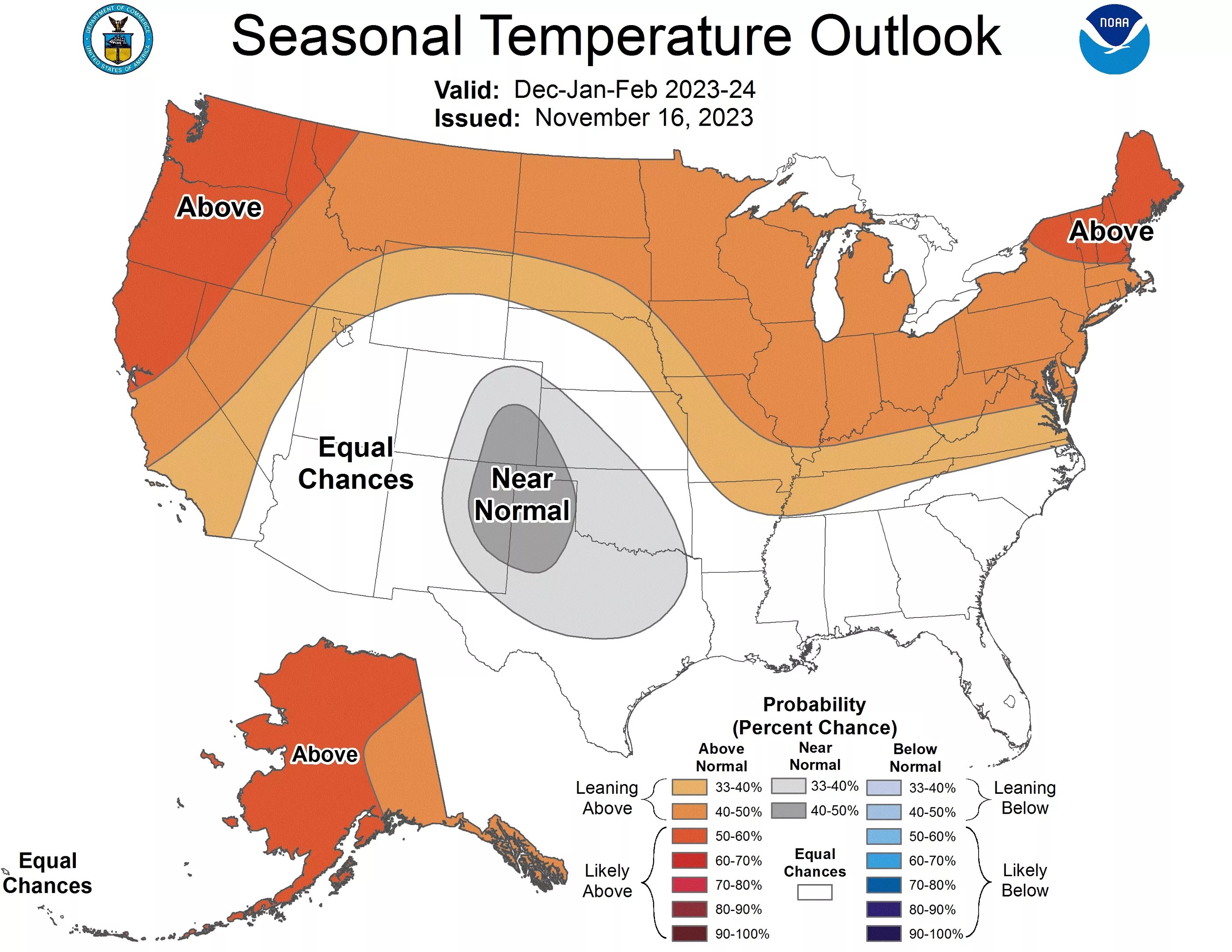

Late in 2023, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center released its outlook for December, January and February, predicting that precipitation across the Centennial State would be slightly above normal and that temperatures had an equal chance of being above or below normal in the western part of the state, and likely near normal in the eastern half.

“Our tools, including dynamical statistical models of climate and the expected impacts from El Niño over your state, had a bit of conflict,” says Johnna Infanti, a meteorologist with the NOAA Climate Prediction Center. “What we would see in our tools are conflicting signals.”

Though the state typically sees some increase in total precipitation during an El Niño event, the forecast isn’t very confident this time around, according to Infanti. The southeastern United States does have a strong likelihood to have above-average precipitation, and the northern states are very likely to be hot and dry. But since Colorado is sandwiched between the areas that are most affected, the changes aren’t as severe.

“It’s not exactly the most confident region of the country where you would see impacts,” Infanti explains. “Every time that we get an El Niño, we might expect some typical impacts, but not every El Niño is the same.”

One thing that’s certain: El Niño is not a predictor of avalanche activity, despite what people believe.

But the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC) can predict avalanches using other means, and issued a special avalanche advisory for the Colorado mountains over Martin Luther King Jr. weekend. “Very dangerous avalanche conditions will develop in some regions, with the most dangerous conditions developing in the middle of the weekend,” it warned. “It will be easy to trigger large, widely-breaking avalanches capable of burying a person. Conditions will be more dangerous than they have been in weeks, so travel plans should be adjusted accordingly.”

In 2018 and 2019 – the most recent El Niño winter – Interstate 70 experienced a lot of avalanche activity in Colorado, but it wasn’t specifically tied to the weather event, according to CAIC Director Ethan Greene.

“It’s both a misconception and also there’s some truth to it,” he says. “When you’re talking about Colorado, we’re sort of in the middle, where those El Niño/La Niña events are not a great predictor. It is something that we can think about, but we don’t know exactly how it’s going to play.”

Colorado is likely to have more rain and snow in the coming months than usual.

NOAA Climate Prediction Center

For example, Greene points to how the top of the state could get much less precipitation than usual, while the bottom could get more.The CAIC won’t be able to predict avalanche likelihoods until the snow falls.

“How avalanches form and how cycles build and release is a fairly short-term progression,” Greene says. “It’s really hard to talk about things season-wide, because the avalanche conditions are produced by both the series of weather events that lead up to a particular time frame and the weather that’s happening during that time frame. The order that those events happen is important.”

Even an extremely wet winter isn’t always a good predictor of avalanches, which occur when layers in the snowpack crystalize differently next to each other.

“What happens when you’re releasing an avalanche is that because of the difference in the mechanical properties of two adjacent layers, you can get a crack that forms in the snowpack and will propagate on its own,” Greene says. From there, the crack can dislodge a large slab of snow and spiral.

To predict avalanche activity, the CAIC goes into the mountains to examine and identify structural weaknesses. According to Greene, every weather event throughout the winter creates its own layer in the snowpack that is identifiable – like the rings of a tree.

“Whether it’s a big snowstorm, or a big windstorm, or even just a few days or a week of dry weather, we’ll get these layers that form,” he tells Westword.

Early snowfall can cause problems later on in the winter, so the CAIC is keeping an eye on certain areas of the central mountains that got the first flakes, Greene says. By comparison, the San Juans were much drier earlier, so the CAIC is waiting to see what might build up there.

The two halves of Colorado have different temperature outlooks this winter.

NOAA Climate Prediction Center

Avalanches can be triggered naturally through weather events, but they can also be set off by people. Even a person as small as 140 pounds can take the wrong step and release thousands of tons of debris, Greene says.

“The movie narrative that is not true is that it’s really unlikely that you’re going to trigger them with sound,” he notes. “So if you yodel, you’re probably not going to trigger an avalanche, but if you go out into the mountains and throw a stick of dynamite onto the right slope at the right time, you could.”

Some avalanches occur in isolated areas, but others happen near busy roadways. About 500 avalanche paths are close to state and federal highways. The CAIC closely monitors these spots, and if it appears one is unstable, it works with the Colorado Department of Transportation to close down a road at a slow time and trigger an avalanche preemptively, when there’s no traffic.

There are numerous avalanche paths along I-70, as well as Berthoud and Loveland passes. As a result, the CAIC encourages drivers to check the avalanche forecast before they head to the mountains.

“The most important thing is to get that current information so you know how to build a plan for where you’re going to go and what you’re going to do that keeps you safe,” Greene says. “If you’re going to spend time in avalanche terrain, taking a course where you are out in the field with an instructor is a really good thing to do.”

It’s also recommended to travel with rescue tools – such as an avalanche transceiver, pro pole and shovel.

“If you’re driving, the most important thing is to be prepared for winter driving by having some extra clothes and food and water, a full tank of gas, good tires, and then obey the road closures,” Greene says. “If, for some reason, you are in a place where you are driving and there’s an avalanche, what you want to do is stay in your car and wait for CDOT and the other emergency services workers to come to get you out.”