"Do not think we're trying to copy anyone," he tells some future, unseen audience. "We had the idea before the first one ever happened. Our plan is better, not like those fucks in Kentucky with camouflage and .22s. Those kids were only trying to be accepted by others."

With his parents asleep upstairs and Dylan Klebold manning the camera, Harris takes his viewers on a tour of his bedroom arsenal. On the floor, he's laid out numerous pipe bombs, a shotgun and carbine with spare clips, boxes of bullets and homemade grenades. He models his cargo pants and the slings he's devised to hold weapons. He brandishes a knife and points out a swastika carved in its sheath. He shows off a fifty-foot coil of bomb fuse hanging on the wall.

"Directors will be fighting over this story," Klebold says. "I know we're gonna have followers because we're so fucking godlike. We're not exactly human. We have human bodies, but we've evolved one step above you fucking human shit. We actually have fucking self-awareness."

Welcome, once more, to the basement tapes -- nearly four hours of posing, boasting and bitching by the obnoxious gods of self-awareness, two teenage killers-to-be named Harris and Klebold. The footage was shot in the last weeks of their short lives, the final segment just a few hours before the rampage at Columbine High School on April 20, 1999, that left fifteen dead and seriously injured two dozen more. Seized by Jefferson County investigators right after the shootings, the tapes have been sitting in an evidence vault for the past seven years, seen by almost no one -- except, of course, a small army of cops, attorneys, reporters, victims' families, expert witnesses and assorted hangers-on.

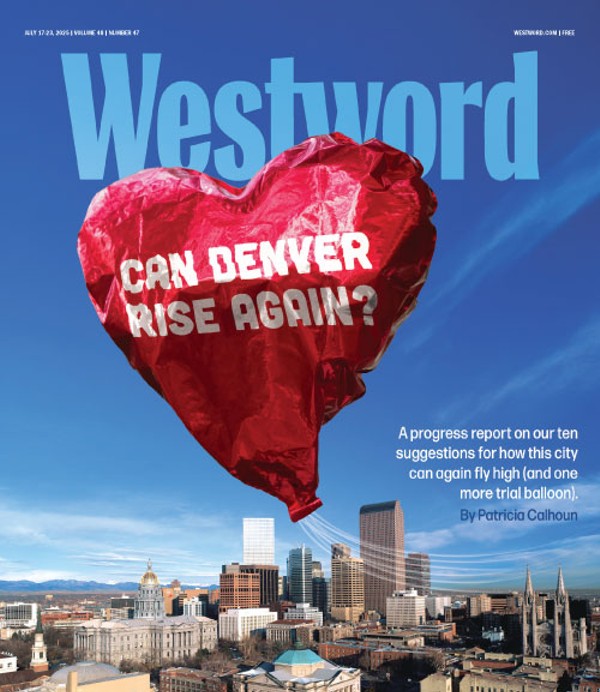

That could change soon. Following a surprising decision by the Colorado Supreme Court last fall, which held that the tapes are part of the "records" generated by the Columbine investigation, Jefferson County Sheriff Ted Mink has been wrestling with the biggest quandary of his law-enforcement career. Should he refuse to release the basement tapes on the grounds that their dissemination is still (in the words of the state's Criminal Justice Records Act) "contrary to the public interest" -- and thus prolong a five-year court battle with the Denver Post? Or should he make the hate-filled rants, along with other long-suppressed writings and recordings taken from the killers' homes, available to the world at last?

Mink has postponed announcing his decision until after the seventh anniversary of the massacre next week -- out of respect, his office says, for the victims' families, some of whom have pushed for the release of the materials while others have opposed it. But if history is any guide, he will oppose the release, sending the whole controversy back to court. County officials have treated the killers' writings and tapes as an anthrax-like deadly contagion that must not, under any circumstances, be inflicted on an unsuspecting populace.

"The Sheriff's Office is fearful that release of this information would not help the public but could potentially cause another one of these attacks," Assistant County Attorney Lily Oeffler said in a hearing before District Judge Brooke Jackson in 2002. (Oeffler, the county's point person in keeping Columbine's secrets, is now a district judge herself.) The county's position mirrors that of the parents of Harris and Klebold, whose attorneys have maintained that the tapes are private property and that their release would have a disastrous "copycat effect," inspiring more school shootings.

"Mr. and Mrs. Harris do not want the angry and vitriolic rantings of their son to be made public," Harris attorney Michael Montgomery wrote to Mink recently, "but their overriding concern is to avoid the risk that these tapes and writings might influence others to commit similar acts."

Noble sentiments, to be sure. But the lofty case for suppression has been undercut by the actions of Mink's predecessor, John Stone, who didn't seem to have a problem infecting the public with the gunmen's vitriol when it served his own purposes. Like Poe's purloined letter, like the bomb fuse Eric Harris kept on his wall and that his parents viewed as an innocent decoration, many of Columbine's remaining secrets aren't all that hidden. They have trickled out over time -- largely through the leaks, blunders and self-serving half-truths produced by the Columbine investigation itself.

Copycats and Natural Born Killers

In his official report on the massacre, Sheriff Stone used excerpts from the writings of Harris and Klebold to suggest that no one but the gunmen could be blamed for the shootings -- no one at the sheriff's office, anyway, which had failed to investigate several previous complaints about Harris. This kind of selective editing was anticipated by the killers; in one of their videos, they discuss how the cops will censor their work and "just show the public what they want."

Stone also gave a Time reporter full access to the basement tapes. Claiming to have been bushwhacked by the resulting cover story, the sheriff was then compelled to let local media types and victims' families view the tapes before locking them up for good ("Stonewalled," April 13, 2000).

Similarly, Stone's office had no qualms about sharing tidbits from Harris's journal -- "the Book of God," as Harris calls it in one video -- in presentations to select gatherings of school and law-enforcement officials. As long as the cops could control the information flow, there was no yammering about the dangers of copycats.

But it was a different story when Westword and then the Rocky Mountain News published more extensive excerpts from Harris's writings. The excerpts showed that Harris had developed detailed plans to attack the school a year in advance, while he was in a juvenile diversion program and supposedly being investigated for building pipe bombs and making death threats ("I'm Full of Hate and I Love It," December 6, 2001). Now officials were outraged that their top-secret investigation had sprung yet another leak.

So was the Denver Post. Tired of getting its ass whupped in the leak department, the Post went to court to demand the release of the rest of the materials seized from the killers' homes. Attorneys for the county and the killers' parents responded with a flurry of dire warnings about copycat effects, including one from David Shaffer, a psychiatrist and expert on adolescent suicide. In addition to a 27-page resumé, Shaffer submitted a four-page affidavit asserting the toxic nature of the basement tapes, which he hadn't seen.

Some judges involved in the Columbine litigation have uncritically embraced the copycat argument, saying the disclosure of the materials would have "a potential for harm" or, in fact, would be "immensely harmful" to the public. Judge Jackson, who ultimately may have to decide the matter, has been more skeptical. In one hearing on the basement tapes, he pointed out that there were plenty of Columbine imitators before the existence of the tapes was even disclosed. All the more reason, Oeffler responded, not to release them.

"What evidence do you have today that release of the documents is going to cause some calamity, or are we just speculating?" Jackson demanded.

"Unless you release the evidence and they actually cause the calamity, Your Honor, the question cannot be responded to," Oeffler shot back.

"Does that mean I can't, and no court can ever release them because maybe some additional copycat is going to be inspired?"

"I don't think it is a maybe, Your Honor," Oeffler responded gravely.

Yet Harris's web writings, several pages of his journals and detailed descriptions of the contents of the basement tapes have now circulated on the Internet for years, with no notable surge in copycat incidents. The problem with the copycat defense is that it is speculative and thus largely unanswerable, much like forecasting suicide clusters based on suicide coverage in the media. (It's just as speculative, perhaps, as trying to quantify the number of shooting incidents that might have been prevented by frank discussion of the Columbine tragedy.) Some of the same experts who consider the Klebold and Harris materials too dangerous for public consumption also blame the massacre in part on "the gunmen's previous exposure to violent imagery and their study of notorious criminals and tyrants." Does that mean it's time to pull Mein Kampf from the library shelves or Natural Born Killers from the video store, simply because Harris admired Hitler and Klebold took his style tips from Woody Harrelson?

In several cases, news reports of would-be school shooters note that the suspects had trenchcoats or otherwise sought to imitate Harris and Klebold -- but how many were actually "inspired" by them? It's true that the gunmen wanted their words to find as wide an audience as possible in order to attract followers; but then, they, like the sheriff's office, had an exaggerated notion of their own importance. The county's efforts to suppress the killers' writings and tapes have given them a cachet of consummate evil and menace; being taboo, they've become cool. Yet anyone who's actually seen the tapes or read the journal fragments soon recognizes that these fabled mass murderers are not gods but adolescents. Angry, scared, mocking, disturbed, bitter, pathological, deluded (fucking self-aware, mind you), emotionally stunted and deadly, but adolescents just the same. Behind the blather about being gods and kick-starting a revolution is a bottomless obsession with their own lack of status and sense of injury. Behind the bravado, a snivel.

"I don't like you," Klebold says in one of the videos, addressing two female classmates. "You're stuck-up little bitches. You're fucking little...Christian, godly little whores! What would Jesus do? What the fuck would I do?"

"I would shoot you in the motherfucking head!" Harris chimes in. "Go, Romans! Thank God they crucified that asshole."

"Go, Romans!" Klebold echoes, and the two start chanting like sophomores.

Far from adding to the hype, the leaks have helped to demythologize Harris and Klebold. Showing the tapes in their entirety could have some deterrent value, one victim's parent has suggested, removing whatever lingering mystique the killers still have.

Wayne's World and the Clueless Klebolds

In his letter to Sheriff Mink, Harris attorney Montgomery contends that the single media viewing of the basement tapes six years ago "should be deemed sufficient...to insure public transparency in the investigative and prosecutorial decisions of executive agencies." But what's striking about the drawn-out records battle is how little transparency there's been.

From day one, mortified county officials did their best to conceal the existence of an affidavit for a warrant to search Harris's home that was drafted a year before the shootings but never submitted to a judge ("Anatomy of a Cover-Up," September 30, 2004). They kept it under wraps for two years, until CBS News found out about it and Judge Jackson ordered its release.

Investigators lied to the media about what the sheriff's office knew about Harris and Klebold before the shootings. They gave victims' parents bad information about how their children died. In an effort to make the facts of the police response to the attack fit the official story, timelines were distorted or destroyed and dispatch logs and other key documents spirited away, in defiance of court orders and open-records requests. Small wonder that critics of the sheriff's office believe that, copycat concerns aside, the powers that be have other motives for keeping the remaining materials in the vault.

Some clues to What They Don't Want You to Know can be found in the basement tapes and in the Harris writings first published in Westword in 2001. The lads boast about how easy it is to fool adults in general and their parents in particular. They mock some of their lamer teachers, and Klebold offers a hearty fuck-you to a sheriff's deputy who, it turns out, had more contact with the pair than his department was prepared to admit. Harris exults in how easy it was to buy guns and ammo, how absurdly easy to dupe everyone around him.

"I could convince them that I'm going to climb Mount Everest or I have a twin brother growing out of my back," he says. "I can make you believe anything."

None of this is terribly complimentary to school officials, law enforcement, the supervisors of the diversion program the teens were both in -- or the parenting skills of the Harrises and Klebolds. And it raises disturbing questions about what similar revelations might be contained in other, as-yet-unreleased materials.

Evidence logs indicate that police found much more than the basement tapes and the "Book of God" when they searched the Harris home. Harris left other handwritten notes behind and at least one audio message -- a microcassette labeled "Nixon" that was left conspicuously on the kitchen counter. According to a brief internal police summary of the tape's contents, Harris can be heard explaining "why these things are happening and states it will happen Œless than nine hours [from] now.'"

But the most intriguing, hush-hush item from the Harris home is probably evidence item #201, a green steno book found in a desk drawer. The book doesn't belong to Eric or God but to Wayne Harris, who used it to write down various matters concerning his son's mental health, errant behavior and interactions with neighbors and authorities. As a result of the confidential settlements reached in lawsuits brought against the Harrises and Klebolds by some victims' families, virtually everyone who's ever seen the steno book can't comment on its contents.

We do know one thing about item #201: It documents more contacts between the Jefferson County Sheriff's Office and the Harrises over their son's behavior years before the shooting than the sheriff's office has ever acknowledged. In 2004, investigators working for the state attorney general's office used the steno book to track a complaint against Eric that dated back to 1997, a case for which the department paperwork had disappeared. The deputy on the case, Tim Walsh, was the same officer who arrested Harris and Klebold for breaking into a van in 1998; interviewed by investigators after the shootings in 1999, Walsh made no mention of the 1997 case.

Wayne and Kathy Harris have never given a formal interview to the police. Their chief contact with Columbine investigators occurred the day of the shootings, when officers arrived to search the house, and particularly Eric's room, despite Kathy's protesting, "I don't want you going down there." But the parents' attorneys have had extensive communication with the county attorney's office since that day, and they've joined forces with the county on numerous occasions to battle release of the steno book and other materials seized from the home. It's a cozy alliance that has troubled Brian Rohrbough, whose son Danny was murdered at Columbine and who has ended up opposing the team in court.

"Jefferson County has used taxpayer money to represent the Klebolds' and Harrises' demand that these items never be released," Rohrbough wrote in his own letter to Mink, urging him to release the materials sought by the Post. "It is long past time for you to serve the public's interest in protecting children above the private interest of two families who raised cold-blooded murderers."

Nothing akin to the green steno book was found at the Klebold home. Tom and Susan Klebold did talk to investigators; five years later, they even gave one media interview, to David Brooks of the New York Times. "They say they had no intimations of Dylan's mental state," Brooks wrote. That assertion is spectacularly at odds with accounts from school employees -- about chronic disciplinary problems, perceived "anger issues" Dylan might have had with his father, and, most of all, a class essay Dylan wrote about a trenchcoated avenger who slaughters a group of "preps," a scene so vicious that his teacher felt compelled to discuss it with his parents -- but Brooks didn't press the issue.

Written only weeks before the massacre, the essay wasn't Klebold's first foray into violent revenge fantasies. He wrote about killing sprees in his own journal, as well as thoughts of suicide, depression and his dream of ascending to a higher state of existence. The sheriff's report provides only brief references to this material, which has been more tightly guarded than the Book of God.

When the sheriff's office finally got around to releasing thousands of pages of Columbine material, a cover sheet for one section was titled "Klebold Writings." But the writings weren't released.

The High Priests

One proposed solution to the question of the killers' tapes and writings, advanced by Ken Salazar before he left the post of Colorado attorney general for the U.S. Senate, was to turn over the materials to a "qualified professional," who would author a study about the causes of Columbine while keeping the primary materials in strict confidence. The proposal soon fell apart, though, after the killers' parents refused to cooperate with Salazar's anointed expert, Del Elliott, director of the University of Colorado's Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence.

It's just as well. The notion that only the high priests of social science are qualified to handle the gunmen's toxic waste, that only the academic elite have the training, the lengthy resumés, the godlike self-awareness to process this information without becoming hopelessly contaminated, is absurdly creepy. It's Kleboldish.

Besides, there's no data to suggest that qualified researchers are any better at keeping a secret than the Jefferson County Sheriff's Office. Lack of access to the basement tapes, the Harris and Klebold journals and the green steno book hasn't discouraged amateurs and experts alike from producing "psychological autopsies" of the killers, but there are two researchers who've had unique access to all those items. The only catch is that they can't talk about it.

In the course of defending one of the Columbine lawsuits, Solvay Pharmaceuticals -- the manufacturer of an anti-depressant prescribed for Harris -- retained the services of two expert witnesses, Park Dietz and John March, who were allowed to examine confidential discovery materials, including the tapes and writings seized from the killers' homes. Dietz and March were subject to the same suffocating non-disclosure agreements imposed on parties to the lawsuits against the Klebolds and Harrises. But after the Solvay case was settled, the pair sought permission to publish their findings in a peer-reviewed journal.

Lewis Babcock, chief judge of Denver's federal district court, denied their request. In a scathing order, he pointed out that March and Dietz had made conflicting arguments about why they should be allowed to go public. On the one hand, much of the material had already leaked out; on the other, the pair claimed to have "important scientific evidence of the motives and reasons" for the massacre that had not yet come to light. If the first assertion were true, Babcock reasoned, then the experts' report would be "of no interest to the public" -- but if it contained new information, it could endanger "potential victims of those who might take encouragement" from what it revealed.

In other words, damned if you do, damned if you don't. Babcock was also unconvinced by the idea that the experts were in a better position to grasp the essence of Columbine's remaining mysteries than a layman would be. "The public is equally adept at comprehending the depravity under which Harris and Klebold labored," he wrote.

But the public's adeptness depends on having access to the facts -- not just bits and pieces of the story, but the whole ugly package. That hasn't happened with Columbine. It's been a sorry tale of lies and coverups, of stonewalling, cover-your-butt officials and oblivious parents and suffering without end. Harris and Klebold relied on just such a climate of denial and deception to allow them to plan their massacre and practically advertise it, without fear that they would ever be seen for who they were.

It's been seven years since the pair walked into Columbine for the last time, guns blazing. The world has other monsters on its mind now. Yet there are people who still contend that the words the killers left behind are so powerful, so evil that the average citizen must never hear them.

The truth hurts. But the lies can be lethal.