Courtesy of Heather Patterson

Audio By Carbonatix

September marks the beginning of the new art season, with the long-running shows of summer finally closing and the first of the fall shows opening. Goodwin Fine Art is coming out strong with a pair of heavy-duty solos: Rebecca Cuming: XXI Century Field and David Hicks: Stone Flora & Blue Cuttings. Gallery owner Tina Goodwin’s pairing of the Cuming paintings and the Hicks ceramics is inspired. Though the works are very different visually, they share a conceptual underpinning: What start as depictions of plants wind up as abstracts. Wes Magyar

The magisterial and sometimes monumental Cuming paintings, which are in the front, operate on two distinct levels. They’re lyrical floral abstractions, but they also make political statements. A good example of this is “Kandahar,”a huge horizontal panel depicting a field of red flowers that’s organized according to one-point perspective, with the guiding lines visible in the composition. In the extreme foreground are rough approximations of the blossoms, which recede into tiny splashes as they march toward the horizon line at the top. Cuming’s methods here border on action painting, with the pigments appearing to have been applied quickly, with splashes and smears. The resulting surface is highly three-dimensional, covered with lumps and hollows of paint. The political content of the piece is more subtle. The flowers Cuming has rendered are poppies, and Kandahar is a province in Afghanistan; thus, the real subject of the work is the opium trade. Even more explicit is “Dixie,” its sunny palette of buff, sienna and cream contrasting with slave shackles that are nearly hidden by the cotton plants in the foreground. Installation view: Paintings by Rebecca Cuming, ceramic sculpture by David Hicks. Wes Magyar

Denver, make your New Year’s Resolution Count!

We’re $17,500 away from our End-of-Year campaign goal, with just a five days left! We’re ready to deliver — but we need the resources to do it right. If Westword matters to you, please contribute today to help us expand our current events coverage when it’s needed most.

A few of Hicks’s ceramic sculptures are displayed among the Cuming paintings, but the bulk are in the back. Most of them relate to flowers, but some also refer to fruit, plants and even cut stems. Like Cuming’s paintings, the sculptures have an ideological subtext, but the content here is more personal. The pieces reflect Hicks’s disconnect from nature, as he views the farm fields near his home through the windshield of his car as he zooms past them. Probably the clearest expression of this separation are the sculptures made up of elaborate supporting frameworks of welded metal rods, onto which Hick has mounted ceramic elements. For “Construction Rose,” he built a complex spider web of rods that were bent into loops to fit a variety of botanically derived ceramic shapes. The juxtaposition of the rods’ textural character and that of the shapes conveys the disconnection. Also bifurcated visually is “Char,” in which scores of individual black pendulum shapes are hung by individual cords from a bracket on the wall. More formally unified are several smaller ceramic sculptures from the artist’s “Clipping” series, which typically include a cylindrical, vessel-like shape surmounted by a twig or flower. Installation view, ceramic sculpture by David Hicks. Wes Magyar

A few blocks away, Walker Fine Art is also starting strong, with Experimental Surroundings, a group effort to which gallery owner Bobbi Walker has devoted the entire space. The show includes pieces by a half-dozen artists – painters, sculptures and installation artists – who’ve all created distinctive pieces that somehow go together. One reason for this success is that the organizing theme is fairly broad, essentially just abstraction with some source in nature; another is that each of the artists is shown in depth, in a dedicated space, allowing viewers to move from one artist’s section to the next. “The Fractal Nature of Things,” by Melissa Borrell. wood & paint. Abbey Arlt

The show begins in the double-height window space with a handful of works by Melissa Borrell, including the enormous installation “The Fractal Nature of Things.” Meandering over the two-story north wall, the piece is built of painted wooden circles that have been slotted together like a balsa-wood model airplane. The colors of the circles alternate between tangerine and white; although every part is geometric, and the title even mentions fractals, the whole takes on an organic shape evocative of a coral outcropping. “Cluster Dynamics,” on the opposite wall, is similar if more complex. From left: “Juggling With the Natural Order,” “Shade” and “Survival Instinct,” by Deidre Adams, acrylic and mixed media on panel. Abbey Arlt

Next up are paintings by Heather Patterson, who takes a more-is-more approach to the landscape-based pictorial elements she employs in her densely populated compositions; the elements occupy different picture planes so that they become layers of shapes and lines stacked one on top of another. This approach is not unrelated to the one taken by Deidre Adams, though her efforts look nothing like Patterson’s. While Adams also uses layers of imagery, she sets them into atmospheric color fields. The imagery often has a calligraphic character and in places is reminiscent of graffiti; Adams incorporates little renderings that are vaguely representational as well. Abbey Arlt

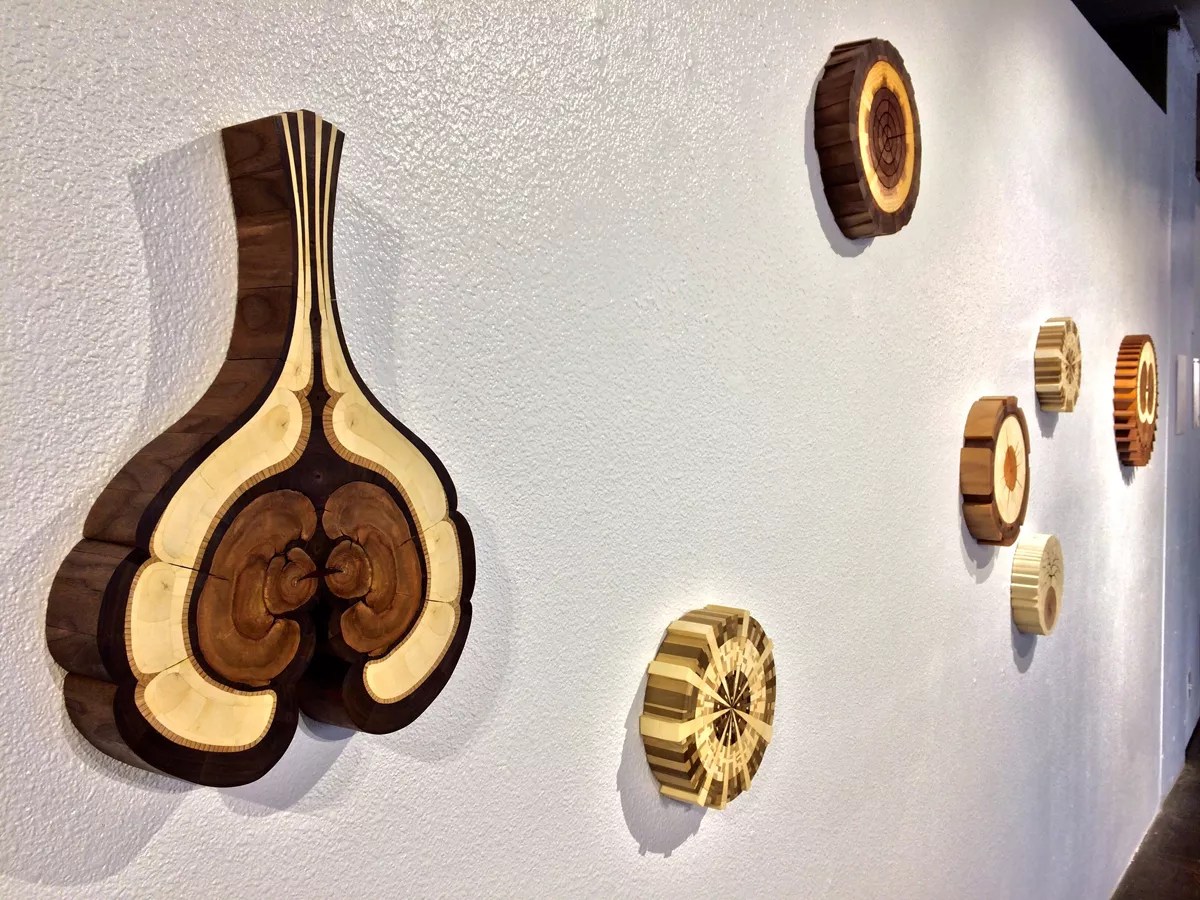

Wood assemblages by Chris DeKnikker, which are all tondo-like wall hangings, represent a cross between abstraction and representation. DeKnikker gathers up found wood and even bark, then cuts it into shapes that he joins together. The pieces here include his signature geometric patterns, but also reveal a new interest in conveying recognizable images. Rather than assemblages of repeated shapes, the newer pieces are more like inlays, with the subjects conveyed through specially cut wooden shapes that suggest a tree or the internal organs of the body, among other imagery.

Kim Ferrer works in wood, too, and she has created a multi-part installation that expresses her feelings about moving from the country life on a farm to the city lights of Denver. “Memory Chest,” a wooden chest with a hinged top, is empty, waiting to be filled with her new adventures, giving the otherwise melancholy installation a sense of hopefulness.

From left to right: “Poena,” “Poseidon” and “Aeolus,” by David Mazza.

Abbey Arlt

In the center of everything is a set of large floor sculptures by David Mazza, who hasn’t shown in town for a few years; the brief absence makes this work look super-fresh. The sculptures are all tall and narrow, with triangulated, interconnected open forms. They’re made with polished stainless steel as well as mild steel, with a little surface rust and some pre-existing finishes; the contrast between the dull patination of the mild and the mirror finish of the stainless steel is wonderful

The nip in the air means the art season is upon us, and it’s off to a good start with these solid shows.

Rebecca Cuming and David Hicks, through October 28 at Tina Goodwin Fine Art,1255 Delaware Street, 303-573-1255, goodwinfineart.com.

Experimental Surrounding, through November 4 at Walker Fine Art, 300 West 11th Avenue, #A, 303-355-8955, walkerfineart.com.