In the middle of the commotion, lobbyist Cindy Sovine-Miller stands at the brass railing in the Capitol’s south atrium, positioned between the imposing entrances to the House and Senate chambers. Dressed in a smart-looking dress and jean jacket, the 37-year-old is flipping through a bill she’s printed out, scanning the arcane language. Like many of the bills she’s been interested in this session, this one concerns marijuana.

A Colorado farm girl and lifelong Republican, Sovine-Miller has been working at the State Capitol for eighteen years, nearly all of that time lobbying for health-care companies and other powerful businesses. That changed last year, though. While she’s now lobbying for early childhood, education and alternative-energy interests, the majority of her caseload this session has been devoted to cannabis.

Sovine-Miller is far from the only one working with that industry. While Colorado’s legal recreational sales started on January 1, 2014, and its medical marijuana program thirteen years before that, many basic questions regarding how to manage the state’s medical and recreational cannabis markets are still being hashed out at the Capitol. This session alone, lawmakers have pondered how to regulate cannabis consumption in social environments, whether to allow marijuana deliveries, how to scrub criminal records of marijuana offenses that are no longer crimes, whether cannabis and hemp should be treated like other agricultural products, and what to do if the Trump administration decides to shut down legalized marijuana once and for all. Decisions on these matters won’t just shape a state industry that took in roughly $1.3 billion in sales in 2016; they will set an example nationwide as other legalized-marijuana states, from California to Massachusetts, follow in Colorado’s footsteps.

“Think of this as, we’ve framed the house,” says Sovine-Miller. “Now we’re having to put the rest of it together.” And the people doing the heavy lifting, the ones really calling the shots over the future of cannabis in Colorado and beyond, are often lobbyists like Sovine-Miller.

No wonder the Capitol is crawling with more than two dozen cannabis lobbyists. According to Frank McNulty, the former Speaker of the House who now lobbies for anti-marijuana organizations, marijuana lobbyists outmatch lobbyists on his side by about four or five to one. Nearly all cannabis lobbyists work for marijuana trade groups like the Colorado Cannabis Chamber of Commerce or such major cannabis brands as LivWell and Mindful.

Sovine-Miller, however, is different: She spends much of her time working for marijuana patient interests, doing a lot of that work pro bono. For years, the marijuana patient community ceded ground at the Capitol to increasingly powerful industry interests. But over the past two legislative sessions, patients have scored one major victory after another: The passage last year of “Jack’s Law,” which allowed medical marijuana in schools; the recent softening of a legislative assault on home grows that, in its original form, would have triggered upheaval in the state’s patient and caregiver community; and a bill to add PTSD to the list of the state’s qualifying conditions for medical marijuana, legislation ready to be signed by the governor.

With all of these issues, Sovine-Miller was pulling the strings behind the scenes. “These things would not have turned out the way they did if she had not been there,” says Stacey Linn, a patient activist and mother to Jack Splitt, the namesake of Jack’s Law. “No one used to lobby for the interests of the patients, because we don’t have any money. But now with Cindy, there’s a new voice that can hold people accountable.”

That’s exactly what Sovine-Miller is aiming to do right now — hold someone accountable. The legislation she’s looking at this morning, Senate Bill 275, which is moving through the Senate, is designed to authorize new medical marijuana research. But a single line in the bill has been struck, making a crucial change to the scientific advisory council that for several years has been in charge of determining which research receives funding from marijuana taxes. Up to this point, the council had included a patient advocate who has been exempt from needing to have scientific expertise. But thanks to this single change buried on page three, in the future the patient advocate would need to have scientific experience. Sovine-Miller just learned of this tweak from one of the patient advocates she works with: Teri Robnett, executive director of the Cannabis Patients Alliance, who not only currently serves as that patient advocate, but helped launch the medical marijuana research program in the first place. If this bill goes through as is, Robnett would lose her seat on the council."No one used to lobby for the interests of the patients, because we don’t have any money.”

tweet this

Sovine-Miller steels herself and marches up to one of her colleagues: Kara Miller, lobbyist for the Marijuana Industry Group, the trade group behind the bill. Miller is the biggest name in marijuana lobbying at the Capitol, having pioneered the field in 2010. But right now, Sovine-Miller is in no mood to show deference.

She shows Miller the line in the bill that would remove Robnett from the advisory council. “How did this happen?” says Miller, her face expressionless. “Who asked for this?”

“I don’t know,” says Sovine-Miller. “I wasn’t at the stakeholder meeting.” Meaning she wasn’t invited to be part of the group that helped develop the bill.

“Let’s strike it and see who complains,” says Miller.

“I don’t think anyone will,” Sovine-Miller replies. The subtext seems clear: No one is likely to complain about getting rid of the change because it’s hard to imagine anyone other than Miller or MIG behind it.

After this exchange, when Sovine-Miller returns to the railing, she’s so upset she’s shaking. “I’m sad that this has even happened,” she says. “We are so far behind as a patient community that this is acceptable.”

To some, the matter might seem minor — a technical tweak to an obscure regulatory board. But to Sovine-Miller, the issue represents a far greater concern: ongoing efforts to remove patient advocates and marijuana activists from the political bargaining table. And as she likes to say, “If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.”

“People always ask, ‘Why don’t you run for office?’” says Sovine-Miller. “I always say, ‘Why have one vote when you can work with a hundred?’”

She’s sitting in her office in an old brick residence just a few blocks from the Capitol, surrounded by parking lots. The room is bare — the walls largely unadorned, the desk empty, a phone, stapler and Yellow Pages collecting dust on a side table. She hasn’t had time to decorate since she moved in at the beginning of the year. Even before the session started in January, her real work was at the Capitol: persuading senators or representatives to sponsor legislation she wants passed and working with bill drafters to make sure the language comes out just right. After that, she has to monitor those bills, tracking their progress and permutations as they wind their way through various readings and committee hearings. She also needs to watch for new bills dropping all the time, any one of which could impact her clients. Through it all, she works with crucial interest groups, folks ready to descend in force on the Capitol to ensure that her legislation gets through — and the ones who plan to stand in her way. Plus she has to identify key lawmakers integral to deciding whether a given bill is killed or becomes law, so she can pull them aside in the Capitol’s rose marble hallways to try to sell them on her position in three minutes flat.

The tools of her trade as she works these halls are as uncomplicated as her office: a basic leather portfolio where she keeps copies of bills she’s working on or is interested in, and an honest, friendly, even bubbly manner that belies the slick lobbyist stereotype. “For most lobbyists, it’s a game,” says Kayvan Khalatbari, co-founder of Denver Relief Consulting, which has contracted with Sovine-Miller this session. “Even if they care about the topic, the job has voided their soul a bit. Cindy is different. She still seems fresh, even though she’s also very accomplished. She can rally people and tug on their heartstrings.”

Sovine-Miller could have subcontracted a glossy office at a big lobbying firm this session, but right now she wants to be a lone wolf, doing what she needs to do without other lobbyists looking over her shoulder. And then there’s something about this quiet old building, owned by a real estate attorney who worked with her father, that reminds her of all that she went through — all that she lost — in order to get here, doing this work.

She grew up in Deer Trail, a sleepy town of 400 on the eastern plains. Her father was a wheat and cattle farmer, her mother a cosmetologist. Raised as a Catholic and a fiscal conservative, Sovine-Miller learned early that it’s best to give people a hand up, not a hand out. Her high school civics teacher noticed her knack for arguing and told her to consider going into politics. When she shadowed her state senator at the Capitol as a high school senior, she realized he was right. “I was sitting in the floor of the chamber, and it was insane,” she says. “Everyone was talking to each other, no one was listening to the person up front, but everyone knew when to vote and what to do. None of it made any sense. It was total chaos, and I wanted to be right in the middle of it.

Becoming a single mom at twenty while studying political science at Metropolitan State College of Denver didn’t derail her plans. She took classes online, at night and on the weekends while working full-time at the Colorado Legislative Council, the nonpartisan research arm of the Colorado legislature. There she learned how she could leverage the arcane rules of the General Assembly to her advantage — how she could use the legislative process to bring a bill back from the dead after it had seemingly died in committee, for example. After short stints lobbying full-time for the Colorado Hospital Association and working for a big lobbying firm, Sovine-Miller started her own lobbying company in 2006.“When you have activists who are leading the charge because of their passion and emotions, sometimes that distracts from the message.”

tweet this

She focused on early childhood and health-care issues, areas where she figured she could have the most impact on people’s lives — and also areas that were lucrative. “The money was in big industry — pharma, hospitals, insurance,” she says, “and I was really good at it.” Among her signature accomplishments was a 2010 bill that allowed insurance companies to offer discounts to members who became healthier by participating in wellness programs. “I had forty lobbyists working against the bill,” she says, “and I was among the only ones working for it.” She can count on one hand the number of bills she took the lead on and lost.

Because of her health-care work, Kara Miller and another cannabis lobbyist approached her years ago about working for medical marijuana interests. She turned them down. “At that point, I made the decision to stay away from highly controversial issues,” Sovine-Miller says. “I was playing it safe.” She also found her work at the time rewarding: “I felt I was building systems and infrastructure to help people,” she remembers.

That started to change when she got a call from her mother in 2012. Her father had cancer — on his tongue, then in his lymph nodes, then everywhere. The chemo treatments did nothing but ravage his body as he became sicker and sicker, and the doctors treated him like one more faceless patient. Still, she criticized her mother when she learned she wanted to give her husband medical marijuana. “There is no evidence,” Sovine-Miller remembers telling her. “You should leave it to the doctors, to the people who know what they’re doing.”

Sovine-Miller changed her mind when the tumor on her father’s face shrank from the size of a softball to that of a baseball within three weeks of starting medical cannabis, when he was able to say his goodbyes to his family before passing away in February 2015.

She didn’t just lose her father. She lost faith in a lot of the work she’d been doing for nearly fifteen years.

“I saw my dad go from being a vegetable in a hospital waiting to die to being at home again, thanks to a plant,” she says. “I had spent my career helping to build a system that was failing people. I said to myself, ‘I can’t do this. I worked for the wrong people.’”

Before the end of the 2015 legislative session, she cut ties with every one of her clients. Suddenly she was unemployed, not knowing what to do. She was picking up odd jobs when a woman named Stacey Linn showed up at the Capitol during the 2016 session. Linn had heard that Sovine-Miller was a lobbyist, and she needed help passing a bill. Her teenage son, Jack Splitt, had severe cerebral palsy and used medical marijuana to manage it, but he wasn’t allowed to use it at school. The year before, Linn had worked to pass “Jack’s Amendment,” which gave schools the option to allow medical cannabis, but her son’s school and every major school district in the state still refused to change their policies about making it available to young patients. Now Linn needed to pass something that would require schools to do so.

“Here is that moment to redeem yourself for when you were a jerk to your mother when she put your dad on cannabis,” Sovine-Miller thought to herself. So she told Linn she’d help.

Sovine-Miller leveraged the connections she’d made over the years, especially with Republicans, explaining to lawmakers that the issue wasn’t about teenagers smoking pot in school parking lots. She navigated opposition from the Colorado Association of School Boards and helped keep health-care interests out of the fight. She also organized moving testimony from medically fragile children from all over the state. That included Linn’s son Jack, whose charisma charmed the most jaded legislators. “I put those families on a pedestal and helped shine a light on them to help them tell their story,” Sovine-Miller recalls. “Those kids and their mothers propelled the bill through.”

But Linn thinks Sovine-Miller deserves part of the credit. “I was floored by her tenacity and how good she is at what she does,” Linn says. “She is not a glory hound, but she did a lot of the behind-the-scenes work.”

Jack’s Law, requiring that medical marijuana be allowed in schools, passed with the support of 92 of the state’s 100 legislators. The supporters included all 35 state senators, who stood during the bill’s final vote, many of them with tears in their eyes.

Two months later, the bill’s namesake passed away. Sovine-Miller supported Linn as she grieved. The two had become close friends, and the lobbyist had found a new cause.

“These medical marijuana patients are like my dad,” says Sovine-Miller, her voice cracking. “They are scared, they are sick, they need this medicine to live, and now they’re taking this issue on as their mission.”

Now it was her mission, too.

“Welcome to ground zero,” says Teri Robnett. She gestures at her desk, which takes up much of the living room in the cozy bungalow that the 58-year-old shares with her husband, Greg Duran, near Regis University. By this point in the legislative session, it’s piled high with bill drafts, fact sheets and handwritten planning notes, not to mention bottles of pills and a marijuana vape pen that Robnett uses for her fibromyalgia.

For years, this room has been ground zero for the state’s medical marijuana patient movement. A former web marketing consultant who co-owned Denver’s Big Tree Pedicab Management with Duran, Teri got a crash course in cannabis in 2009, when she became communications director at the Peace in Medicine Center, one of Denver’s first dispensaries. Then, after Amendment 64 passed in November 2012 and Robnett learned there was no medical marijuana patient advocate on the task force to determine how to implement recreational marijuana in the state, she took it upon herself to become a de facto member. She attended nearly every meeting and spoke up to ensure that medical marijuana concerns weren’t lost in the planning process. Around that same time, she used a $30,000 inheritance she’d received after her brother died of prostate cancer to launch the grassroots organization Cannabis Patients Alliance. Now, while Duran takes the lead in running the Good Lab — a private consulting lab based in their home that tests marijuana for patients, caregivers and others who can’t access other Colorado testing facilities because they aren’t licensed marijuana businesses — Robnett spearheads one advocacy effort after another. Her work has led former state marijuana czar Andrew Freedman to label her “the patient advocate of Colorado.”

Robnett can play the political game, shmoozing at fundraisers and speaking succinctly and compellingly during testimony at the Capitol. When it’s needed, however, she’s willing to unleash grassroots passion, filling the Capitol with angry patients when there’s no other way to stop a bill. “People now know we can play nice,” she says, “or we can make things really ugly.”

At first, marijuana businesses worked closely with Robnett. “The industry loved me,” she remembers. “I was advocating for good policy, which benefited them.” But that changed as the industry grew larger and more entrenched, and many of the patient protections Robnett was fighting for became a threat to the industry’s bottom line. “We don’t have the financial backing the industry does,” she says. “What the patients have is people and sympathy and media.” But those resources go only so far as marijuana businesses develop political and financial clout and the state becomes increasingly dependent on massive recreational marijuana tax revenues. (The governor has proposed using marijuana revenues to fund affordable housing, and as the session was winding down, lawmakers floated the idea of increasing recreational cannabis sales taxes to balance the state budget.)

For years, the best Robnett and other patient advocates could do was hold off truly disastrous legislation. So while new legislation has allowed the recreational market to develop in new and exciting directions, the state’s medical marijuana program atrophied. Doctors now face new penalties for making too many medical marijuana recommendations, and unlike recreational marijuana products, medical marijuana still isn’t required to be tested for pesticides and contaminants. Robnett is afraid that medical marijuana will eventually be subsumed by the adult-use market, where prices are higher, potencies are lower, and products aren’t geared toward patient needs. Last year, Washington state shut down nearly all of its medical dispensaries, forcing most patients to buy their medicine, at a slight discount, from recreational shops. “I think there is definitely a push in that direction here,” says Robnett. “It’s coming.”

But when Sovine-Miller first approached Cannabis Patients Alliance about helping stem that tide this legislative session, Robnett balked. While she’d been impressed by Sovine-Miller’s work on Jack’s Law, Robnett’s opinion of the lobbyist had soured when, late in the 2016 session, she’d helped kill a child-welfare bill. Sovine-Miller was worried the bill put a target on the back of every Colorado family that used cannabis as medicine, but the legislation had been the culmination of years of work by Robnett to turn advocates of drug-endangered children from adversaries to allies. “It was incredibly devastating,” Robnett says of the bill’s defeat. For that, the Cannabis Patients Alliance honored Sovine-Miller with its 2016 “Brutus Award,” given to the person who most betrayed them.

Still, Robnett could see that Sovine-Miller was gearing up to get things done during the 2017 session. The national drug-reform advocacy group Drug Policy Alliance had hired her to advocate at the Capitol for social-justice issues such as child-welfare reforms. “To have a lobbyist with a personal story like hers who at the same time can play a bipartisan role? That really can’t be beat,” says DPA state director Art Way. And when the Hoban Law Group, a Denver-based cannabis law firm, hired Sovine-Miller to help shepherd a bill to add PTSD to the state’s list of medical marijuana conditions, an issue Robnett had been working on for years, she agreed to work with the lobbyist, too.

Sovine-Miller, along with Robnett, veterans’ advocates and parent activists like Linn, helped neutralize opposition to the PTSD bill from several dozen health-care lobbyists, allowing it to eventually pass in both the Senate and the House. But in the middle of that process, a bigger issue dropped: a bill backed by the governor to limit marijuana home grows to twelve plants statewide. The goal was to keep the black market from taking advantage of Colorado’s liberal home-grow laws — until then, patients had been allowed to grow up to 99 plants and consolidate their allowances in untracked greenhouses — to grow and ship cannabis out of state. But the law would have been devastating for medical marijuana patients, says Sovine-Miller. “The only people who need more than twelve plants are the extremely medically fragile,” she says. “Most of them cannot afford the volume of plant material they need from dispensaries for their medical concentrates, and if they did, they’re concerned it would be laden with pesticides.”

“The big boys in the industry think they’re being proactive and lobbying for their own protection.”

tweet this

Sovine-Miller went to work. At the governor’s office, she dangled the threat of Robnett marshaling an army of medical marijuana patients at the Capitol, armed with empty pill bottles and bright-orange shirts reading “Medical marijuana patient and future felon.” The marijuana industry, which might otherwise support limiting home grows in order to drive more business to their stores, was kept at bay by the unspoken threat of publicizing the pot business’s role in out-of-state cannabis diversion. (There’s a reason that a border town like Trinidad, population 9,000, boasts more than a dozen pot shops.) The result was the passage of a home-grow bill with major concessions to the medical marijuana community. Once signed by the governor, the bill will allow patients to grow up to 24 plants at home as long as they have a doctor’s recommendation and register with the state; that plant count is high enough to cover the vast majority of existing patient home grows. “This will make us the first state in the country to successfully create a closed-loop regulatory system for home grows,” says Sovine-Miller. The bill also marks the first time Colorado has defined what constitutes a marijuana plant in a home grow; as a result, law enforcement can no longer use seedlings, clippings and clones to inflate plant counts in marijuana arrests.

Bob Hoban, managing partner of the Hoban Law Group, thinks Sovine-Miller was critical to these victories. “Cindy was able to create stability and keep the ship together,” he says. “When you have activists who are leading the charge because of their passion and emotions, sometimes that distracts from the message. I’m not saying that would have happened here, but there was a chance for that to have happened here.”

Still, Sovine-Miller didn’t win every battle this session. After Initiative 300 passed in November 2016, allowing social marijuana consumption at some Denver businesses, the state’s liquor and tobacco enforcement division passed a rule banning operations with liquor licenses from participating. Denver Relief Consulting, lead backer of the initiative, hired Sovine-Miller to fight the new rule. She says she nearly had the regulation overturned at the legislature’s Committee on Legal Services — but at the last minute, liquor lobbyists rallied in support of the rule, keeping the dual-consumption ban on the books. This was one of her first inklings that she’d be going up against established industries threatened by cannabis reforms. “The alcohol industry is probably our biggest foe right now,” says Khalatbari. According to him, alcohol interests are scared that legal marijuana use could cut into liquor sales. That could be why the anti-marijuana organization Smart Colorado counts among its major sponsors the Adolph Coors Foundation, founded by the multibillion-dollar Coors beer dynasty.

Outside business interests aren’t the only ones challenging marijuana reforms. Sovine-Miller’s attempts to remove barriers to entry into the cannabis industry have been opposed on multiple occasions by lobbyists theoretically on her side. Early in the 2017 session, while lobbying for a cannabis trade school, she approached the Marijuana Enforcement Division about allowing out-of-state students to obtain a marijuana occupational license so they could get hands-on training in dispensaries. MED staff offered to go one better, suggesting that they remove the residency requirement for all types of occupational licenses. But when the Marijuana Industry Group’s Miller learned of the proposal, she told Sovine-Miller she’d fight the far-reaching change. “Our position was to support exemptions to the residency requirement for temporary work permits as originally proposed and passed by bill sponsors,” says MIG executive director Kristi Kelly in an e-mail.

“Why would anyone in the industry oppose removing the residency requirements when the MED was perfectly okay with it and it would make everyone’s lives easier?” asks another cannabis lobbyist, who requests anonymity.

Khalatbari says that established marijuana interests were similarly protectionist when he worked to pass Initiative 300. No major cannabis companies or industry groups supported allowing consumption clubs in Denver. “They don’t want people stepping into their territory — I get it,” he says. “But at the same time, they have completely lost sight of the patient, the consumer, and making sure this is an environment that is best for them.”

Along with being the only marijuana lobbyist who spends the majority of her time on patient issues, Sovine-Miller is one of the few cannabis lobbyists who doesn’t also work for clients that many marijuana activists would consider the enemy: alcohol businesses and pharmaceutical firms. And the feeling is mutual: Both industries have supported anti-legalization efforts in other states. Along with the Marijuana Industry Group, Kara Miller represents the Colorado Licensed Beverage Association, the Korean Retail Liquor Association of Colorado, the Colorado Distillers Guild and AbbVie pharmaceuticals. Brock Herzberg, who does marijuana lobbying for Miller, also works for GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson and the Wine Institute. Solomon Malick and Brett Moore, lobbyists for the Colorado Cannabis Chamber of Commerce, count among their clients Astellas Pharma and the Colorado Bar Owners Association. And Peggi O’Keefe of the Cannabis Business Alliance lobbies for the Generic Pharmaceutical Association.

“I think this is because the industry is so young; you don’t have many lobbyists at the Capitol who are career cannabis people,” says Kevin Gallagher, executive director of the Cannabis Business Alliance. “For me, personally, it is a concern. I haven’t seen anything super-obvious this session where there was a conflict of interest, but this can certainly be an issue moving forward, depending on what is being passed.”

Some conflicts of interest might already be emerging. Brett More, a lobbyist for the Colorado Cannabis Chamber of Commerce, opposed a bill this session that would have created a new state license for marijuana consumption clubs. According to the Secretary of State’s registered lobbyist database, he did so on behalf of another client, the American Heart Association.

Most of these cannabis lobbyists declined to respond to interview requests. Miller and Herzberg referred questions to MIG executive director Kristi Kelly, who writes in an e-mail, “Like any business relationship, our contractors and consultants are asked to disclose any potential conflicts of interest. If something arises, we address it. This is something that happens at law firms and other service-based providers all of the time.”

Maybe it makes sense for marijuana interests to hire lobbyists with experience in similar industries, like alcohol and pharmaceuticals. But Khalatbari thinks that soon enough, the conflicts of interest between marijuana and larger industries will rise to the forefront, and the current jockeying for power at the Capitol will pale in comparison to political fights to come. “The big boys in the industry think they’re being proactive and lobbying for their own protection, but ultimately they’re going to be trying to protect themselves from bigger industries like tobacco and pharmaceuticals,” he says. “As soon as it’s legalized federally, these marijuana groups are all going to be at a huge disadvantage.”

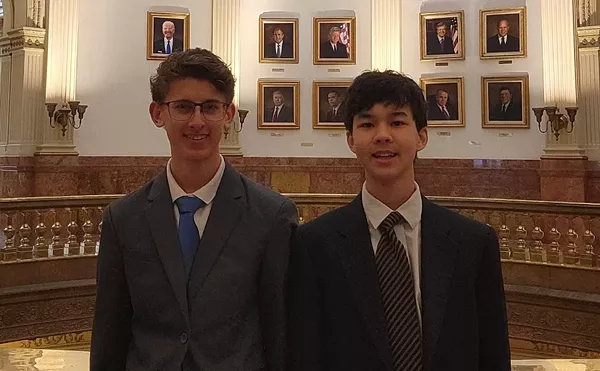

Kayvan Khalatbari thinks the marijuana industry needs to keep an eye on alcohol lobbyists.

Jake Holschuh

“We are excited to see the amendment to ensure that we have a patient advocate that remains on the scientific advisory committee,” says Kara Miller, testifying on behalf of MIG. “From what I understand, that was an unintentional drafting piece.”

Sovine-Miller, sitting in the front row with Robnett and Duran, doesn’t testify. She’s already done her work: prodding Miller to draft the amendment, then asking a Finance Committee member, Republican Senator Jack Tate, to sponsor the amendment, which passes unanimously.

MIG executive director Kelly says neither Miller nor anyone else at the trade group was responsible for the part of the bill that would have excluded Robnett. “We see no reason why patient advocates would be excluded, as they have had a voice in this process from the beginning,” she says. No one else involved in the bill’s drafting claims responsibility for the provision, either. Maybe that language really was unintentional. But even if it was, that part of the bill likely would have stayed in place if Robnett hadn’t noticed it...and Sovine-Miller hadn’t been positioned at the Capitol to fix it.

Situations like this have changed Robnett’s opinion of Sovine-Miller. Usually by the end of the legislative session, Robnett is exhausted and wracked with pain from her fibromyalgia, wondering how much longer she can do such work. This year, she thinks she can keep going, thanks to her colleague at the Capitol. “It’s so nice to have someone else who realizes how hard this work really is, sees the shenanigans going on and recognizes how much the deck is stacked against patients,” says Robnett. “Not only does she see it, but Cindy has chosen to do something about it, putting her reputation on the line for patients.”

This year, Sovine-Miller will be getting the Redeemer Award from the Cannabis Patients Alliance. The organization hasn’t yet decided who will get the Brutus Award; there are so many possibilities.

Robnett testifies at the Finance Committee hearing. She tells its members she appreciates the last-minute fix, but she’s still concerned about what the current bill doesn’t do: require medical marijuana to be tested. “There is no deadline, no guidelines,” she tells the senators. “We hear from patients all the time: ‘Why is recreational marijuana tested and medical marijuana isn’t?’”

With such glitches in the system, Robnett doesn’t see Colorado’s marijuana experiment as a resounding success. “We could have done it all differently,” she says. “We had the opportunity to take a different path and birth a new way of doing business. Instead, it seems that compassion and civil rights have taken a backseat to profit and tax revenue.”

Sovine-Miller plans to work with Robnett and other patient advocates to change that.

Major marijuana legislation still in play just a few days before the session is slated to end include a bill to define “open and public” marijuana use, one to allow for the sealing of misdemeanor marijuana convictions for offenses that are no longer crimes, and one to authorize additional marijuana research and development. Then there’s the last-minute proposal to fix the state budget by increasing recreational marijuana sales tax from 10 to 15 percent. Between that and another recently signed bill that allows cities and counties to levy special local taxes on retail cannabis, marijuana consumers could soon be paying significantly more for their weed. Sovine-Miller worries that sticker shock could lead some consumers to the black market for cheaper prices. “It’s a delicate balancing act,” she says. “This won’t solve our long-term budget problems, and the risks should be weighed carefully given the increased attention on illegal markets.”

Along with the PTSD and home-grow bills, several other significant cannabis bills have passed both houses and just await the governor’s signature. These include Sovine-Miller’s bill that allows occupational training across state lines, a measure that provides flexibility in transferring medical marijuana from one dispensary to another, and legislation that repeals the governor’s Office of Marijuana Coordination — created to oversee the implementation of the initial recreational marijuana system in this state, and no longer needed.

Even as the legislative session ends, Sovine-Miller is getting ready for next year at the Capitol. She aims to tour around the state this summer, learning people’s thoughts about how to effectively regulate businesses that allow cannabis consumption. She’ll be working on potential legislation to allow for cultivation facilities where people can rent out grow space, to help the small number of patients who need to grow more than the 24 plants allowed under the new home-grow law. And she’ll be working on how to pass a “Homeless Bill of Rights” next year, another issue the Republican has embraced and is working on pro bono.

She’s also starting to ponder her own marijuana enterprise: a wellness clinic for patients. She doesn’t want to give too much away — she’s learned how cutthroat this industry can be. All Sovine-Miller will say is that it will be a place that showcases “the power that cannabis can bring to our society.”

Told that makes her sound less like a lobbyist and more like an activist, she just smiles: “That’s who I am.”