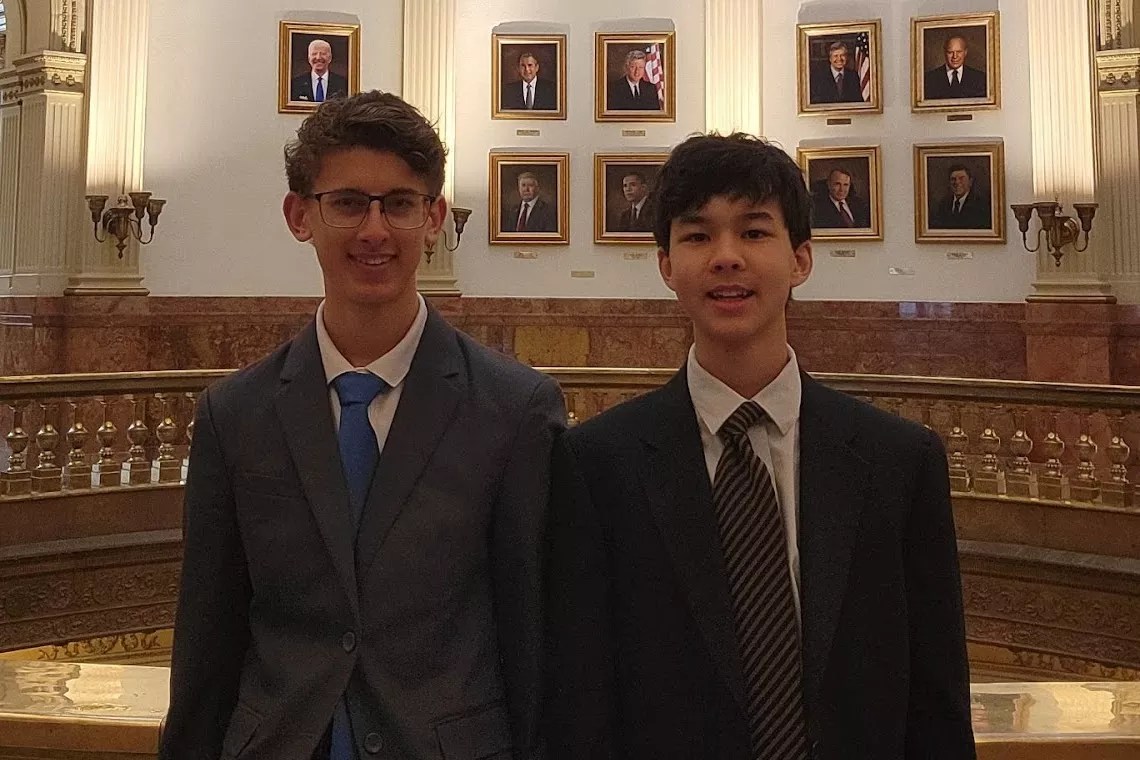

Courtesy of Kiran Herz

Audio By Carbonatix

Kiran Herz and Jaiden Hwang have a lot on their plates as they begin senior year of high school this month: Writing personal statements, securing letters of recommendation…and completely reforming Colorado’s college admission system.

Herz and Hwang are running a ballot measure to grant top-performing Colorado high schoolers automatic admission to state colleges and universities. They’re currently petitioning to qualify for the November 2026 ballot.

The teens say they’ve spent the last three years at Cherry Creek High School watching peers break down from the stress of college applications. They’ve worked hard to prepare – between them, their extracurriculars include the National Honor Society, Model UN, Chess Club, Knowledge Bowl, Professional Careers Club and an e-sports team – but even they aren’t immune to the anxiety.

“It’s always a fear,” says Hwang, age sixteen. “You see all these things online, like, ‘I have a 4.8 GPA, 1600 SAT, sixteen AP classes and I didn’t get into ‘insert school here.” Every year, you see kids who have excellent academics, they write good essays, and they’re stressed out of their minds that they’re not going to get into any college.”

The widespread angst led Herz, age seventeen, to seek a “simpler way” to handle college admissions. He discovered a Texas law passed in 1997 that automatically admits resident high schoolers with grade point averages in the top ten percent of their graduating class to state universities.

More than a dozen other states have developed similar direct admissions programs with varying specifics regarding GPA thresholds and participating universities. The programs span across California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington and Wisconsin, with several more states pursuing pilot programs.

Supporters say automatic admissions programs can boost college enrollment, increase a state’s educated workforce and encourage top high schoolers to stay in their home state for college. The strategy has been praised for engaging first-generation students who may not realize college is an option for them, and for serving as a race-neutral way to increase diversity in universities.

Colorado does not have a statewide direct admissions program. Herz says he wishes legislators would have taken action before; he reached out to his state senator and representative about it, yielding little results.

“It would be amazing if they had, it would be so much stress off of my plate,” Herz says. “But it hasn’t happened. So, it’s up to us to change it for the next generation.”

Their proposal largely aligns with Texas’s law: It would require all state-supported institutions of higher education to automatically admit local students with a GPA in the top ten percent of their high school’s graduating class. It would apply to incoming freshman applicants who graduated high school in Colorado within the prior two school years, and who meet the university’s or college’s class requirements and “rules on moral conduct or code of conduct.”

The Colorado measure adds a cap for automatically admitted students, limiting them to comprising up to 75 percent of a college’s incoming freshman class. The teens say this ensures universities save space for out-of-state students and local students without the highest GPAs.

Some Colorado universities have created their own direct admissions programs limited to specific school districts. In March, the Colorado School of Mines announced that graduating Jefferson County Public Schools STEM students with 3.8 GPAs will be guaranteed admission in 2026. Similar partnerships have emerged between the University of Northern Colorado and Greeley-Evans School District 6, Colorado State University Pueblo and Harrison School District 2, and Adams State University and San Luis Valley school districts.

For smaller rural colleges, the programs are intended to bolster enrollment. Adams State’s enrollment rate was still short of pre-pandemic numbers when it started its direct admissions pilot in 2024. For more prestigious universities like the School of Mines, the goal is to encourage educational achievement for local high schoolers.

Representatives of the School of Mines, the University of Colorado and Colorado State University declined to take a stance on the proposed ballot measure, saying they are not permitted to take positions on election matters.

Jaiden Hwang (left) and Kiran Herz at the Secretary of State’s Office.

Courtesy of Kiran Herz

Herz and Hwang have taken on this endeavor largely on their own, saying they relied only on an AP government teacher and the state’s review boards to tweak their proposal.

They may be the youngest people to get a Colorado ballot measure proposal this far. Colorado is one of 24 states that allow citizen-initiated measures, letting residents bypass the legislature and petition to bring policy proposals directly to voters. Any Coloradan can submit an initiative via a lengthy process that includes receiving approval from Legislative Council Staff, the Secretary of State and the state Title Board, before they can start petitioning.

Students have submitted initiative proposals before, but they usually have a parent or other adult as a co-representative, according to Legislative Council Staff. Staff said they are unsure whether a proposal led exclusively by minors has ever made it to the Title Board before; Herz says the board convened an emergency session to make sure he and Hwang were legally allowed to present their initiative since they are both under eighteen years old.

“We are definitely venturing into uncharted territory,” Herz says. “It’s been fun going along this journey. I just hope it can continue. …Now, we’re at the biggest hurdle.”

That hurdle is collecting 124,238 signatures by December 26 in order to qualify for the ballot. It’s a tall order for anyone, but Herz and Hwang face an additional challenge: They’re not old enough to collect the signatures, or even sign the petition, themselves.

The teens are working to gather volunteers to lead the petitioning effort on their behalf, launching a website for participants to sign up.

“It will require a massive volunteer force. We are hopeful, but we’re not entirely confident,” Hwang says, adding that they are optimistic voters will approve the measure if they manage to make it to the ballot. “I believe there are very few Coloradan individuals who would not want to help students.”

Herz and Hwang will already be in college by Election Day on November 3, 2026, with the ballot measure set to take effect on November 30 if approved by voters.

Herz wants to study political science, psychology or chemistry at Stanford, Northwestern University or the University of Colorado Boulder. Hwang wants to study chemical engineering or medicine at Stanford or Johns Hopkins University.

But that doesn’t matter, they say, because they’re not pushing the initiative for their own benefit. The teens say they want to ease the pressure on their fellow students and encourage them to reach their full academic potential, whether that means going to college when they never intended to apply, or applying to more prestigious institutions because they know they have a safety school secured.

“We’d like to remedy a little bit of that anxiety for future generations,” Herz says. “It would be a dream to finally get on the ballot. …We have a lot of hope, but hope won’t get us to the ballot. Only help will.”