The swirling winds along South Broadway, which splits Denver in half, carry with them a lot of what makes up the city’s past and present, its culture and its vibe. The aromas of street tacos and marijuana float on those winds, as do the sounds of local bands, light rail and heavy trucks. Antique stores, fewer now than there once were, line the sidewalks, next to dive bars, boutiques and, more recently, breweries. If only you could bottle all of that.

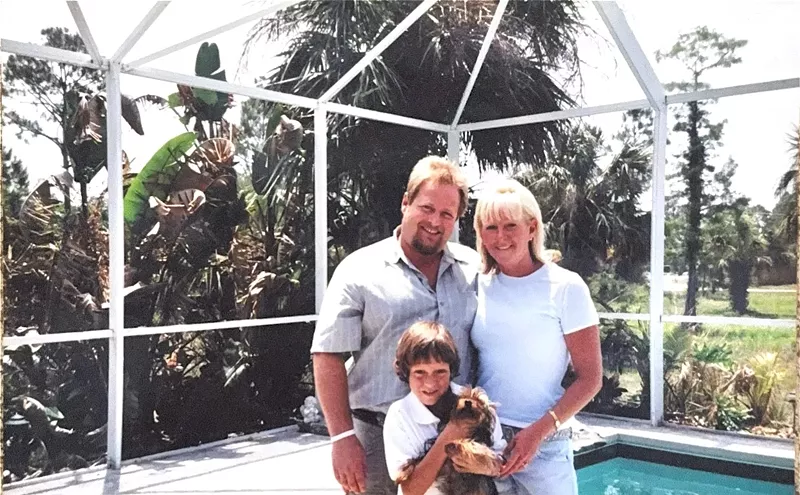

Inside Former Future Brewing, owners James and Sarah Howat are trying.

The Howats poured their first beers in January 2014 — part of a wave of openings that saw the number of breweries in Denver grow from fewer than ten in 2010 to around fifty now. Their focus, both in the tap room and in their beers, was on blending older, more elegant styles with newer, brasher versions. But from the beginning, James, who has a degree in microbiology from Colorado State University, also wanted to do something very, very different. That’s why a side venture, called Black Project Spontaneous & Wild Ales, was born.

James’s goal was to ferment some of his beers solely with the yeast and other microbes that float naturally in the air in Denver. Capturing yeast this way, which was common in Europe for centuries, is typically referred to as “spontaneous fermentation,” because it relies mostly on happenstance: The yeast used in fermentation is what happens to land in an open vat of beer, rather than a cultivated strain consciously selected by a brewmaster. Breweries accomplish this by leaving large vats of wort — beer that hasn’t yet been fermented — uncovered overnight in rooms with the windows open or with open eaves. These vats are known as coolships, or koelschips in Dutch.

“All of these beers are about making something that couldn’t be made anywhere else in the world,” James says. “It’s like terroir in wine.”

And it’s like bottling Denver.

In Belgium, this style is known as lambic. But many brewers had stopped making beer this way by the twentieth century. A few, though, like Cantillon, in Brussels, kept the tradition alive; today, Cantillon’s products are some of the most sought-after beers in the world, and other breweries in Belgium and elsewhere have started making lambics again as well. These fall under the larger category of sour or wild ales, meaning that they have funky, often pucker-inducing flavors and aromas that are produced with wild yeasts, like Brettanomyces, and bacteria. But most sour and wild ales are made deliberately, with specific varieties of these microbes. Not so with spontaneously fermented beers, when a brewer never really knows what he is going to get.

Over the past ten years, only a very few breweries in the United States have tried to make a beer using 100 percent spontaneous fermentation. They include Allagash in Maine, California’s Russian River Brewing, de Garde Brewing in Oregon, and Colorado’s own Trinity Brewing. “This is an old way of making beer, but it’s also not super-well understood by scientists,” James says. “I come from a microbiological background, and I feel like I have a lot of knowledge about regular fermentation. But this allows me to have the freedom to give up control.”

Shortly after opening Former Future at 1290 South Broadway, the Howats began experimenting with spontaneously fermented beers. Here’s how the process works:

First, James designs and brews wort that he feels has the best chance for success in harboring the right microbes. Then, while it is at an almost boiling temperature, he pumps it up through hoses to the roof of his building, emptying the wort into two seventy-gallon stockpots — his coolship. (Because James brews very small batches, he believes the size and shape of the stockpots work better for the cooling process than the traditional shallow pans.) The best time to do this is on fall and winter evenings, when overnight temperatures drop to between 20 and 45 degrees (spontaneously fermented beer can’t be made in the hot summers). Yeast and other microbes, which float on dust particles, land in the wort overnight (screens protect the liquid from larger particles and varmints). As the liquid cools, these agents begin to activate. “Part of why these beers are so special is what happens to them during the first hours while they cool,” James explains. In the morning, he pumps the wort back down from the roof and directly into oak barrels. Then, after about four days, the yeast begins to eat away at the sugar in the wort, bubbling out of the barrels and letting him know it worked.

But just because the yeast has been activated doesn’t mean that the beer will taste good. In fact, at first it all smells like “prune juice and feet,” says Sarah with a laugh. “But it’s so amazing how quickly they go from tasting like that to tasting delicious.”

Still, the Howats have to dump about 20 percent of their batches because they never improve, or because they’re otherwise not up to their standards.

An aviation-history buff, James started calling his semi-secret experiment the Black Project, as a tongue-in-cheek reference to top-secret military research operations. But the Black Project’s cover was blown in October 2014, when Former Future won a bronze medal for Black Project #1, also known as Flyby, in the Experimental Beer category at the Great American Beer Festival. Flyby, a golden ale with a variety of fruit flavors, had been 100 percent spontaneously fermented in the coolship. “We got that medal and thought, maybe we’re on to something,” James says.

This year, Former Future won’t be represented at GABF at all. Rather, the Howats have decided to enter only Black Project beers and to set up their booth as the Black Project. They’re doing this because of the attention they’ve received and as a way to garner national recognition for the brand, which is one of only a few in the country to regularly brew spontaneously fermented beers. “I feel a big responsibility, because not a lot of people are making these kinds of beers,” says James, who is 29. “The lambic and gueuze brewers are keeping this alive, and there is a lot of respect for that in the beer community. We are trying to honor them while still doing something unique and innovative.”

“Former Future has always been a local, community-focused tap room, whereas Black Project is being marketed to a national audience,” adds Sarah. Although the Howats understand that the distinction might be confusing for locals, since Black Project beers are made at Former Future, they feel that marketing separation is crucial. So while Former Future beers are sometimes kegged and sold to local bars and restaurants, for example, they aren’t packaged in cans or bottles. Black Project beers, meanwhile, aren’t kegged, because the batches are much too small. They also aren’t available on tap at the brewery (though the Howats may make an exception during GABF); rather, they’re bottled and sold in extremely limited quantities on specific days at the tap room. The last two releases totaled fewer than 500 bottles. Each time, eighty to ninety people lined up outside before the doors opened, and both batches sold out in a day.

The next bottle release, of Blueberry Dreamland, is scheduled to take place October 4. Although there are only 180 of the 375-milliliter bottles, the Howats guarantee that anyone who is in line by noon will get at least one. “If you want multiples, you may want to get here early, especially with how limited this is and considering the small-format bottles,” Black Project’s Facebook page reads. “Last time the line was formed and growing by about 10 a.m., to give you some kind of baseline on what ‘early’ is.”

“These are people who are really into sour beers, mostly,” James says. “There is a little crossover with our tap-room regulars, but not that much. They are really two different groups of customers.”

These are the same people who don’t mind waiting in line for hours for sour brews from Crooked Stave or Avery Brewing in Boulder, either. And they’re usually willing to pay quite a bit more for a beer: A 750ml bottle of a Black Project beer typically costs $16 to $30. The 350ml bottles are less.

Those high prices are the result of several factors. First, making very small batches of labor-intensive beer takes a lot of time — and a lot of ingredients — and then the beer ages in wooden barrels for at least eight months before it is ready. Once they are bottled, spontaneously fermented wild and sour ales can be aged for many years, increasing in value as time goes by. The reason they age so well is that they are essentially living things; any oxygen that might get into the bottle — which would ruin another beer — will be eaten by the yeast. As the beers age, the funky flavors tend to blend and become more complex, as well.

Earlier this month, the Howats revealed that they’ve purchased more equipment for the Black Project and plan to increase production of the beers. To do that, James plans to brew more batches, starting this fall when the weather cools down. The goal is to be able to release at least 100 cases or more per month and distribute some of them to liquor stores. He’s also talking with custom fabricators who might be able to build and permanently install a bigger, 160-gallon coolship on the roof, “as well as a small roof and screens to protect the cooling wort from rain and pests while still allowing the Rocky Mountain wind to breeze through,” the Howats say in their promotional material, “depositing what we feel are some of the best and most unique mix of truly wild fermentation microbes being used in spontaneous ales worldwide.”

In the meantime, they’re hoping to get some attention at GABF. The Howats will be entering five beers into the competition and pouring them in the convention hall. Four of these beers were originally fermented spontaneously on the roof. Later, James captured the microbes and used them to inoculate even more wort. These are Dreamland, a golden sour; a peach version of Dreamland, aged in Laws Whiskey’s rye barrels; a blueberry version aged in red-wine barrels; and Jumpseat, a dry-hopped sour. The fifth beer, Ramjet, was 100 percent spontaneously fermented with cherries.

But winning medals isn’t nearly as important as taking an old tradition and putting a new and local twist on it, the Howats say. “I think that spontaneous fermentation makes a product that is oftentimes unrivaled when it comes to sour and mixed-culture beers,” James says. “While there is less control, there is so much more diversity in the microbes. The complexities and subtleties are far greater than what you would get from a lab.”

Just like South Broadway.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Billboard - Slot Inline - Content - Labeled - No Desktop",

"component": "23668565",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "STN Player - Float - Mobile Only ",

"component": "23853568",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - 2x Rectangles Desktop, Tower on Mobile - Labeled",

"component": "24956856",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard to Tower - Slot Auto-select - Labeled",

"component": "17676724",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]