Joseph Hutchison

Audio By Carbonatix

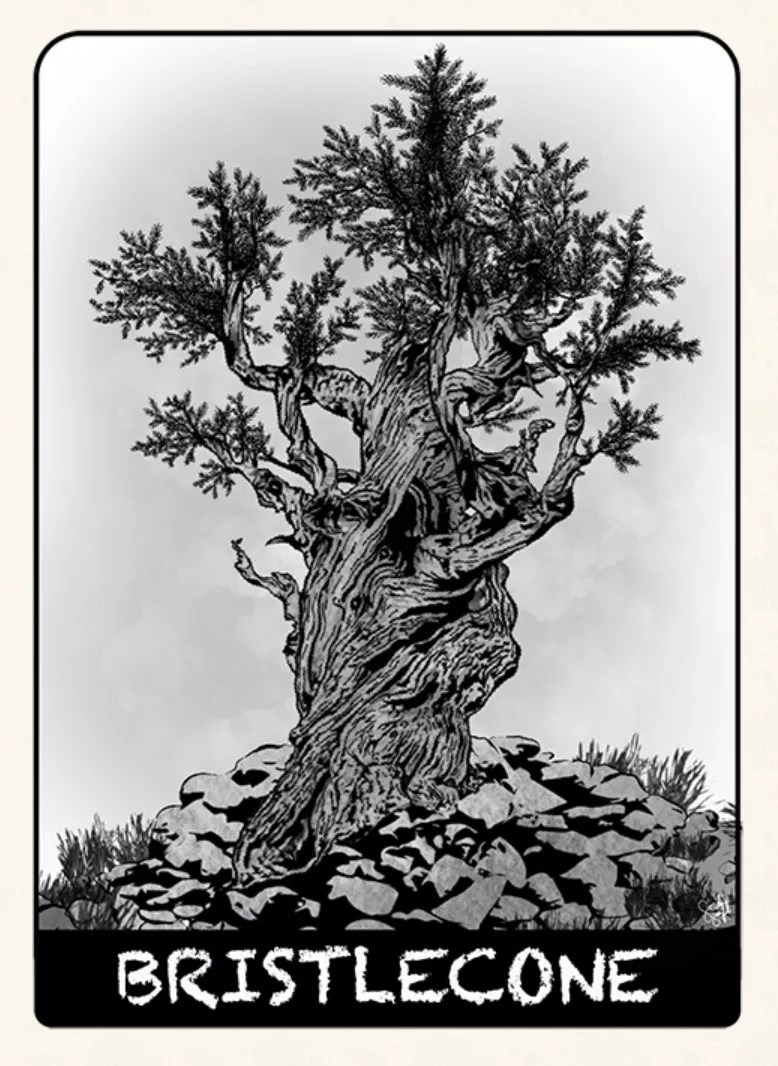

The premiere issue of the poetry journal Bristlecone defines itself by referring to a quote by the great Ezra Pound, from a letter to a young W.S. Merwin: “Read seeds, not twigs.” Combine that with the natural poetry of the titular native Rocky Mountain pine – among the planet’s most ancient and rugged living things – and you have the philosophy of Bristlecone, which is, according to its first issue, “to publish poems that embody qualities that make the bristlecone pine so resilient, long-lived, and worthy of reverence.” The first issue went out in January, and the second is due by the end of February, with a plan to continue monthly from there.

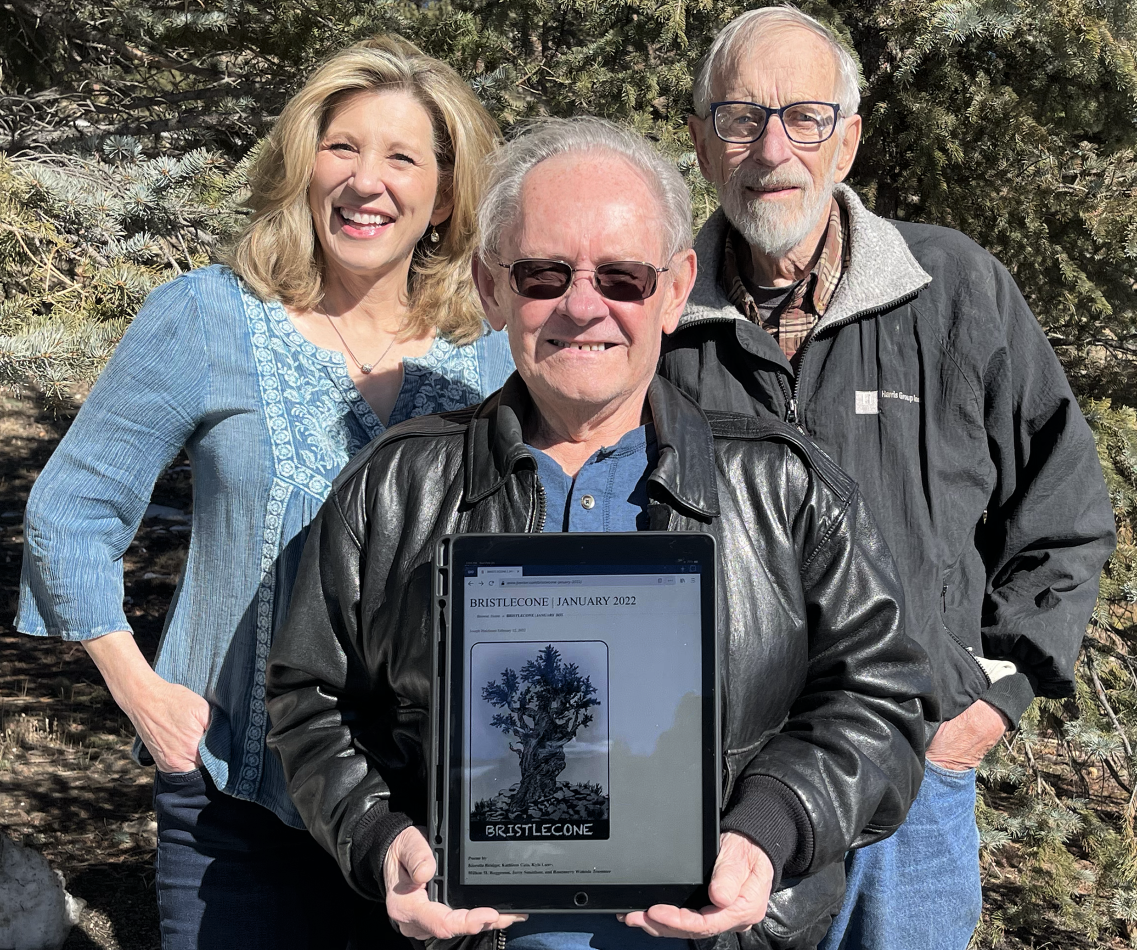

The first issue of Bristlecone.

Sarah Sajbel

The poetry project is modeled after its predecessor, Mad Blood, which began as a reading series and grew into an e-mail magazine in word-document form. Poets would go to a local Evergreen venue for a reading, and their work would be published in missives that followed. The project was founded by Colorado poet Padma Thornlyre, who named it for a line from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet: “…for now, in these hot days is the mad blood stirring.”

When Thornlyre moved to New Mexico, Mad Blood stayed in Evergreen and was then run by Jim Keller and Murray Moulding. When Thornlyre recently expressed interest in rebooting the poetry series from his new home down in Raton, Keller and Moulding spoke with former poet laureate Joseph Hutchison, whom Keller credits with helping to transition Mad Blood into Bristlecone. The former is now ongoing in New Mexico, and the latter, sister-publication-in-spirit Bristlecone, is now beginning its own story in Evergreen.

“The idea is to create a larger sense of community within the Rocky Mountain region,” says Hutchison, one of a group of four editors including Keller, Moulding and Sandra S. McRae. They want to focus on writers from America’s mountain states region. “We’re keeping it manageable for now, limiting ourselves to twenty poems an issue.” That number, Hutchison says, was inspired by the poet Robert Bly and his series of translations, each of which included twenty poems from a particular writer. “[Bly] always thought that was a good size to introduce a poet to a new readership, so that’s what I had in mind.”

The six poets published in the premiere issue include the following:

Kierstin Bridger is a Colorado writer who divides her time between Ridgway and Telluride. She is author of two books: Women Writing the West’s 2017 WILLA Award-winning Demimonde (Lithic Press) and All Ember (Urban Farmhouse Press).

Kathleen Cain has poems forthcoming in the debut issue (online) of Abandoned Mine, and her nonfiction book, The Cottonwood Tree: An American Champion, was nominated for a Colorado Book Award and was selected as part of the Nebraska 150 Books Project.

Kyle Laws is based out of Steel City Art Works in Pueblo, Colorado, where she directs Line/Circle: Women Poets in Performance. Her collections include the recent Beginning at the Stone Corner (River Dog, 2022) and The Sea Is Woman (winner of the 2020 Moonstone Press Award). She’s also the editor and publisher of Casa de Cinco Hermanas Press.

Philippe Ernewein is a native of Turnhout, Belgium, but currently serves as the Director of Education at the Denver Academy. He translates Belgian poet, novelist and art critic Willem M. Roggeman, who was awarded the Order of Leopold II in 1988 for his cultural work.

Jerry Smaldone, who, according to his bio, has “numerous books…waiting impatiently to be published by anybody other than the author.”

Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer is the co-host of the podcast Emerging Form and was the director of the Telluride Writers Guild for ten years. Her poetry has appeared on A Prairie Home Companion, PBS Newshour, O Magazine, Rattle, American Life in Poetry, and her daily poetry blog, A Hundred Falling Veils. Her most recent collection, Hush, won the Halcyon Prize.

One of the ways that Bristlecone will be dissimilar to Mad Blood is that it’s starting with the journal and moving toward on-site readings once that’s a healthy option. “We don’t want to commit to a schedule right now, given the way this pandemic has gone,” Hutchison says. “We’re hoping we’re in the last stages of it, but we don’t want to get ahead of ourselves.” But when possible, the in-person readings will be a major part of the Bristlecone experience.

“We have a couple of bookstores here locally that are interested in hosting,” Hutchison says. “And we’ve talked about other options because of the regional focus. We thought it would be interesting to move around. Like if we had someone working out of Santa Fe, we might set up something there and include a Zoom component so we’d have the best of both worlds.”

The story of Bristlecone might be only just beginning, but Hutchison shares that some of the inspiration for the project’s name comes in tribute to the late poet Rita Kiefer. “She was a member of our writing group,” he says. “A terrific poet, won the Colorado Book Award for [her chapbook collection] Unveiling. She and her husband, Jerry, were also inveterate hikers, and their favorite tree was the bristlecone. Those of us that knew Rita wanted to honor her this way.”

And it’s not just Kiefer that Hutchison wants to recognize. “There’s so much going on in this region deserving of note,” he says. “I was born in Denver, raised in Denver, grew up more or less on the Front Range. When I became Poet Laureate, there were poets on the west slope and to the south and to the north – all over the state of Colorado – that were not part of the Front Range scene at all. I was just blown away by the quality of the work, the energy of the people. We want to draw on that, draw attention to it if we can. The way things are in the West right now, there are a lot of issues and sensibilities that never had as broad a reach as they should. It’s not just New York, Iowa and California. We want to see a little more representation of what’s being done here. Right here.”

For more information, and to read the first issue, see the Bristlecone blog.