Jay Vollmar

Audio By Carbonatix

“I wish I didn’t have so much experience with censorship issues.” That’s the first line of James “Jamie” LaRue’s new book, On Censorship: A Public Librarian Examines Cancel Culture in the US.

But even before the legendary Colorado librarian gets to that line in the opening chapter, he’s dedicated the book “to readers everywhere, whose freedom to read is enshrined in the First Amendment, if they can keep it.” That’s a callback to Ben Franklin’s famous response regarding what sort of government was created by the Constitutional Convention: “a democracy, if you can keep it.”

LaRue is currently the executive director of Garfield County Libraries; he previously worked for 24 years with Douglas County Libraries and has headed the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. Intellectual freedom is also a key to democracy – if you can keep it.

Censorship, in my opinion, is a stupid and shallow way of approaching the solution to any shallow problem. – Dwight D. Eisenhower

There was a time not so long ago when banning books was considered backwards, ridiculous, undemocratic and therefore un-American. Even President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the sometimes-Coloradan known more for fishing than for reading in his downtime, defended freedom of speech.Thirty years later, the 1989 feel-good baseball movie Field of Dreams, which is about as down-home America as you can get, includes a scene at a PTA meeting where a proto-Mom for Liberty (minus the sex scandal, as far as we know) complains about a book, calling it “smut and filth” and even “s-h-i-t.”

If that scene from Field of Dreams was a warning bell, it didn’t resound often enough to work. Instead, the bell was toppled from its ivory tower, carried into the town square, and melted down to make the weapons carried by would-be usurpers in the Capitol on January 6, 2021, a day when one of Colorado’s representatives was posting nonsense about it being “1776.”

That representative – Lauren Boebert, currently the rep for the 3rd Congressional District as well as a candidate for the seat in deeper-red CD4 – was one of the Colorado voices calling for the banning of books last year. Boebert wasn’t complaining about public libraries, but rather those connected to military schools, and proposing that a ban be attached to the National Defense Authorization Act. The books on Boebert’s list were familiar subjects – and some were the same titles being challenged in other library districts and school boards not only in Colorado, but nationwide.

Boebert’s attempt at censorship failed.

James LaRue is a veteran public librarian whose latest book addresses censorship.

Courtesy of James LaRue

During his time in Douglas County, LaRue estimates that he fielded some 250 challenges to what the public library system offered: books, films, magazines, music, even exhibits and speakers. And he’s currently in the midst of another controversy in Garfield County.

According to the most recent data from the Library Research Service, challenges to materials and services in Colorado shot up 500 percent from 2021 to 2022, from 20 challenges (itself double the number in 2020) to 120. According to the American Library Association, there were 1,269 challenges reported nationally in 2022, giving Colorado the dubious distinction of being home to close to 10 percent of all library complaints that year.

The ALA admits that these numbers are somewhat soft; reporting is voluntary, and historically some libraries have been either reticent or simply too busy to forward that information. In fact, the ALA estimates that up to 97 percent of challenges go unreported nationwide.

About 83 percent of the challenges in this state were in some way related to LGBTQIA+ issues, according to the LRS. The most commonly challenged book was the award-winning Gender Queer: A Memoir, by Maia Kobabe; the most frequently challenged activities were assorted drag queen story hours around the state. While no data is yet available for 2023 (these reports are produced mid-year for the previous year), anecdotally the numbers look even higher than in 2022 – despite a success rate of only 1 in 100 for these challenges.

Brooky Parks, librarian and mother of two, worked in the teen section of the Erie Community Library and, in December 2021, was fired for her advocacy of LGBTQ+ and anti-racist programming. Her offense? Using the term “woke” in a positive context. “We have board members that run a library based on their personal beliefs instead of what a library is supposed to be,” Parks told the Colorado Sun. She sued the district for wrongful termination and won her case in September 2023.

In February 2022, the Gunnison County Library System received a complaint from a Crested Butte woman, one of the many state- and nationwide challenges to Kobabe’s Gender Queer. Her request to remove the book was denied, but it led to an even bigger issue about “patron confidentiality” when the library identified the complainant to the media. While the woman had already outed herself in public meetings, the library changed its policy and now redacts personal information when sharing any “request for reconsideration” forms deemed newsworthy.

That September, the public library system in Wellington was hit with a laundry list of books that one local woman considered “pornographic,” including such award winners as Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower and Toni Morrison’s acclaimed The Bluest Eye. The Coloradoan quoted a response from young resident Sienna Zadina: “Not to be rude, but you can’t tell me what I can and can’t read.” This not only turned out to be the overall community’s opinion, but it inspired an interesting solution from the town’s governing board. (Spoiler alert: See below.)

In 2023, Academy School District 20 in Colorado Springs removed three books from its libraries following a letter of complaint from a conservative activist group. The Freedom From Religion Foundation successfully fought the accusation of “inappropriate sexual and violent content,” arguing that the same accusation could be made about the Bible. The books were reinstated, and the conservative group that started the whole thing went dark – though one of its leaders, Derrick Wilburn, was nonetheless elected to the D20 school board in November. (Although initially eager to talk with Westword about both campaigns, Wilburn just as quickly stopped responding to queries.)

Also last year, Garfield County received challenges to various Japanese manga titles from local activists. Although none of the challenges succeeded, they did provoke county commissioners to direct libraries to ensure that young people did not have access to “pornographic materials.” This edict came down just after Hanna Arauza, the sole candidate for the Garfield County Libraries Board of Trustees. was denied a seat, even though the library board had voted to appoint her. Arauza, a resident of Rifle and a library user with small children, was deemed not “representative of Rifle” by the commissioners.

“The denial of my appointment was an example of the library being punished for nothing more than adhering to established policy and legal precedent,” Arauza tells Westword. “They’ve done the community a disservice by leaving the City of Rifle without representation on the library board. The library system strives to serve the entire community. Targeted attacks on obscure books distract from the broader mission of community service and providing resources to all.” What should have been Arauza’s seat still sits empty.

El Paso and Teller Counties have seen not just challenges to specific books, but ongoing efforts to take over boards that make such decisions for a community. “The is mostly part of a coordinated statewide campaign by folks pushing the Moms for Liberty cause and the conservative American Birthright curriculum,” LaRue says.

Moms for Liberty has been labeled an “anti-government extremist group” by civil rights watchdog Southern Poverty Law Center; the Florida chapter was rocked with scandal when an official was revealed as a swinger.

We need not to be let alone. We need to be really bothered once in a while. How long i

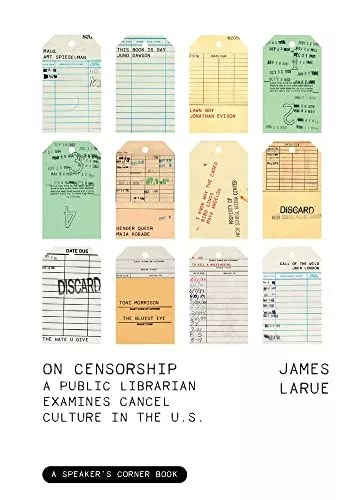

James LaRue published On Censorship last fall.

Fulcrum

s it since you were really bothered? About something important, about something real? – Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

As a result of the challenges he’s fielded, LaRue says his career has involved “hanging out with some very angry people.”

But dealing with anger, and learning to redirect it in constructive and positive ways, was a part of his life early on. He had what he describes as a “very verbally abusive father” who constantly told him he was stupid. “That wasn’t something I believed, mind you,” he says, laughing. “But it was something I was told quite often.”

His connection to literature and libraries comes from his mother, whom he remembers as “kind and interested in books,” and his discovery of the Bookmobile when he was only six. He was playing baseball, so deep into right field that he had little to do, and his mind and eyes wandered. “I saw this blue shimmering haze on the horizon,” he recalls. “It was a Bookmobile. I got so mesmerized that I walked right off the baseball field.”

When he walked into the Bookmobile, he met Mrs. Johnson – the fact that he remembers the name of the first librarian he met emphasizes the importance of this moment – and she asked how she could help him. LaRue said that he’d been reading comic books (mainly Superman) and hearing about something called the speed of light. He wanted to know how they figured that light even had a speed, and also how did they measure it?

LaRue recalls bracing for the inevitable response: What a stupid question. “Instead, her eyes went all a-twinkle, and she said, ‘What a fascinating question. Let’s find out.’ For me, that was the beginning of intellectual freedom. This idea that you honor the curiosity of the child, and you respond enthusiastically to that interest,” he says. “In so much of my life that’s followed, I’ve dealt with that conflict between open curiosity and an authoritarianism that tries to shut down those that try to ask those questions, or to belittle or intimidate.”

He got his degree from the University of Illinois and went to work for the Normal Public Library in Normal, Illinois (which he jokes is perhaps the most misnamed town in America). He left that job in 1979 to hitchhike around the country, ending up in the tiny town of Arivaca, Arizona, just eleven miles north of the southern border, where he helped build a volunteer library.

“When I started working in Douglas County,” LaRue says, “I didn’t consider intellectual freedom as that big an issue.” This was in 1990 – that same Field of Dreams era in which much of America perhaps thought this sort of thing was behind them. “But I’d only been there a very short period when I discovered otherwise.”

There was a local school librarian who was concerned that she was “being hung out to dry” because at the same time that there was a proposed mill levy for the school, a Mormon mom was complaining about a Halloween-themed ABC book, claiming that it was an attack on traditional Christian values. With the mill levy pending, the librarian felt some community pressure to appease the irate patron, so she formed a committee, which ultimately voted to retain the book – but she thought she might still be a political liability. “So I showed up at this meeting,” LaRue says, “and I listened to the woman lodging the complaint do a 45-minute presentation – about 26 letters in the alphabet, right? – about how it was anti-Christian and pagan and offensive and all sorts of things.”

When it was LaRue’s turn to speak, he introduced himself as a new local librarian and also a member of the Intellectual Freedom Committee of the American Library Association, and said that he and his colleagues had noticed a trend: The year following someone complaining about a book, the library in question would say that the problem had essentially gone away – but not because intellectual freedom emerged victorious. Instead, institutions reported that they didn’t have that problem anymore because they didn’t buy that kind of book anymore. “And that’s because their school board had been taken over by the people who lodged the complaints,” he recalls. “Surely, I said at that meeting, in a growing county we need more books, not fewer.”

LaRue got a big round of applause from the 500-plus people in the audience. “I think they felt threatened, intimidated,” he recalls. “They weren’t sure whether they were going to be allowed to talk about this or not. That was my first brush with the censorship issues in Douglas County.”

The books that the world calls immoral are the books that show the world its own shame. ― Oscar Wilde

The most challenged book of 2022.

Oni Press

The case LaRue lays out in On Censorship identifies four reasons that censorship and book-banning are once again on the rise. The first is personal prejudice, which he relates to not liking Brussels sprouts. “They offend me,” he says, describing a meal prepared by his father when he was a child, when he was made to eat these foul-smelling little spoiled cabbages before he left the table. LaRue imagines complaining to a grocer as an adult that the store shouldn’t sell Brussels sprouts: Doesn’t he deserve to be able to come into a store and not see a product that offends him? “Nobody comes to the grocery store because it doesn’t have what they don’t want,” responds the theoretical grocer. “Some people like Brussels sprouts.” In other words, institutions, especially public ones, are not there to serve only an individual’s taste.

Or as LaRue puts it, as a librarian, he’s “not charged with telling everyone else what they’re not supposed to like.”

The second reason is all about “parental panic,” according to LaRue. “When the latchkey children grew up and became the baby-on-board parents – Oh, my God, my children are growing up. I just want my baby to stay a baby – it was a rising tide of parental protectiveness.” He focuses on two age ranges of children whose parents seem most susceptible to this kind of thinking. Parents of children ages four to six are facing the end of infancy and the beginning of childhood; parents of kids fourteen to sixteen are seeing the end of childhood and a slow entrance into the adult world. “It might come in the guise of politics or religion,” LaRue says, “but much of what I was seeing had more to do with this rise of overprotectiveness on the part of the parent.”

The third, which LaRue says he discovered while working for the American Library Association on the national level, involves demographics. “It was there I really discovered this dawning awareness of white, straight America that they weren’t the only actors in the national narrative,” he says. This was a different sort of panic, a different sort of overprotectiveness – not just for some people’s parental identities, but as their baseline identities as normative citizens of this country. “This is where you begin to see complaints about and against LGBTQ+ authors, or books by people of color,” he notes.

And the fourth, LaRue is almost visibly reticent to say, is “simple partisan policies,” the naked want for power. “These are cases in which I’m not sure the complainants really cared about the issues they were raising. But they generated money and they motivated voters,” he says, noting that these “coordinated campaigns” are “cynical manipulations of partially articulated fears to rouse you up and make you outraged, and then force you to do an action that is destructive of the public institutions around us.”

That’s a concept similar to what Eric Hoffer described in his 1951 book The True Believer, which examined the global embracing of authoritarianism in the years leading up to World War II. As he was re-reading Hoffer, LaRue says he was struck that he was “so prescient. Everything that he was saying about setting the groundwork for authoritarianism was happening right now.”

LaRue points to “the rise of aggrievement, this sense that the narratives that tie our histories together were broken and people were casting about to find something that was greater than them and an enemy they could attack.”

The more LaRue thought about the comparison, the more he determined that America is at a tipping point. “It might even be a global tipping point,” he says. “Just a few institutions – education, libraries, the media – stand between us and the rising tide of tyranny.”

The Wellington Library has faced challenges.

Wellington Library Facebook

For every complex problem, there is a solution that is clear, simple, and wrong.– H.L. Mencken

A century ago, author/philosopher H. L. Mencken really got to the heart of today’s challenge: The easy solution – if a book offends you, make it disappear – is wrong.

According to the American Family Association, a far-right Christian fundamentalist organization, a recent survey found that over 60 percent of parents agreed that school libraries should restrict children’s access to books based on their age or parental permission. AFA President Tim Wildmon warns that “the horror stories continue to multiply regarding the pernicious content made available to children,” referring to what he believes is content that’s “sexualized” and “Marxist-inspired.” Wildmon concludes by lamenting that “the days when parents could implicitly trust their public schools and libraries have sadly disappeared.”

That would be a powerful statement – if it weren’t diametrically counter to other data in that survey, which also found that over 80 percent of those same parents said they trusted school librarians to select appropriate books and materials for school libraries.

So what’s the right thing to do? On Censorship ends with seven suggestions: Laugh, Talk to Your Children, Read More Books, Support Newspapers, Volunteer, Attend Civic Meetings and Speak Up. The book goes into detail on each of these, and also offers an in-depth discussion on the role of our libraries in society and culture, and how they play an important role in our past, present and future. “It could be that this recent surge of library challenges is just what it looks like, a callback to 1938 and the precursor to a clash between authoritarianism and democracy. It could be that it’s a marginal last gasp of a generation…that bitterly protest[s] its own loss of relevance,” LaRue writes toward the end of the book. Or it could be “the rise of a new, strong and more dynamic world, more deeply linked, cleansed, and tempered by conflict. We have a choice.”

Wellington, Colorado, chose to deal with its conflict in a uniquely encouraging way. When a mother in the town of under 12,000 residents just north of Fort Collins demanded that the library ban nineteen books that she and a small number of supporters called “pornographic,” the outcry on both sides was sudden and very loud, but the discussion was constructive. In the end, the Wellington Board of Trustees voted in favor of a resolution that prevents the board from restricting library materials – essentially banning book-banning.

The only vote against came from the husband of the original complainant, who just happened to sit on the board.

Democracy in action.

Jamie LaRue will be at the Denver Press Club at 6:30 p.m. March 14 to discuss On Censorship: A Public Librarian Examines Cancel Culture in the U.S. Tickets are $10; find out more here.