John Burcham

Audio By Carbonatix

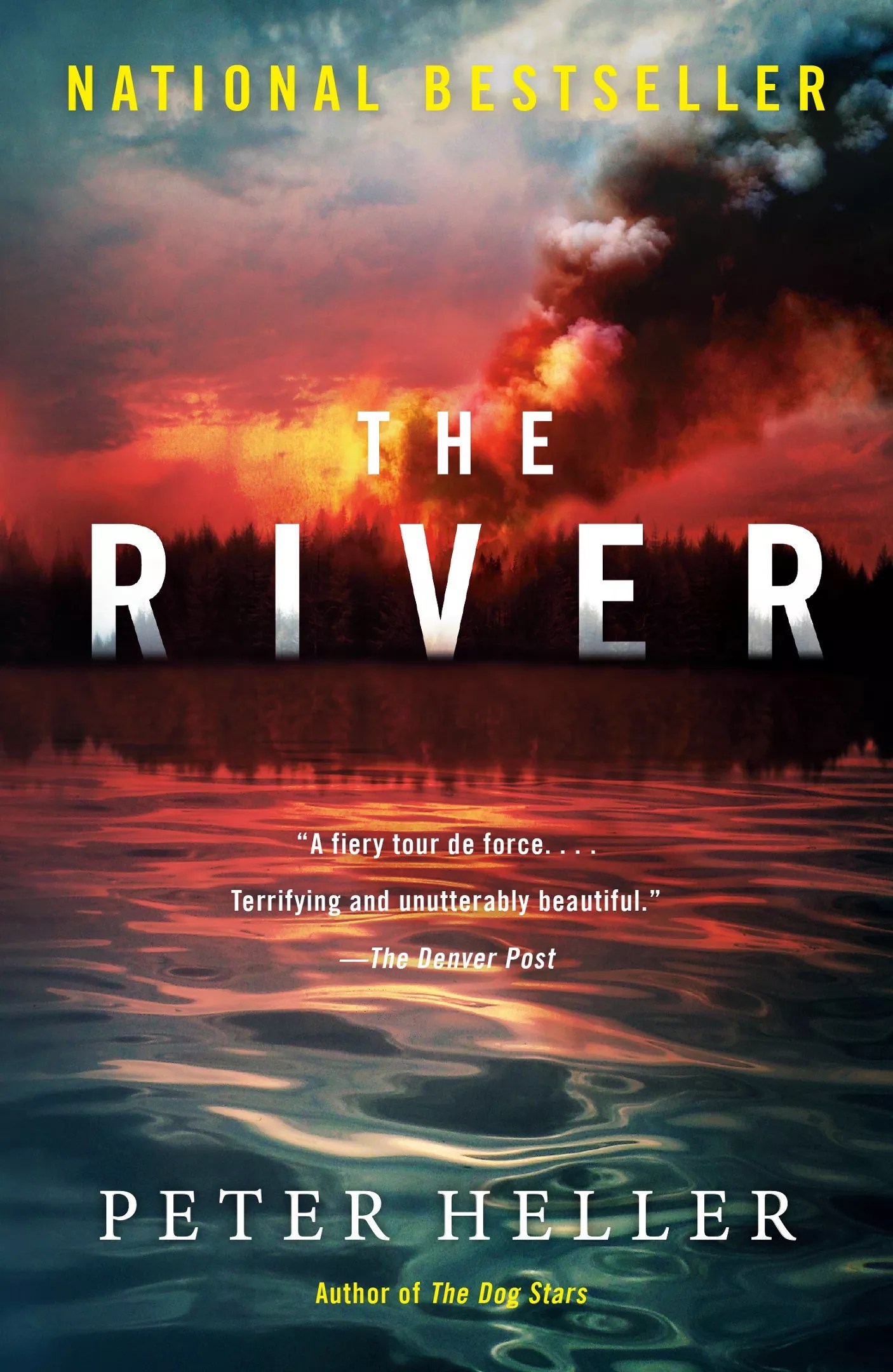

Best-selling novelist and writer Peter Heller has been penning award-winning books for close to a decade. The Dog Stars was a post-apocalyptic novel set in Colorado in the fallout of a disastrous flu epidemic (current health crisis notwithstanding). The Painter won the Colorado Book Award (among several others) in 2014. Celine was an Entertainment Weekly top-ten most-anticipated book for 2017.

We caught up with Heller in advance of his March 11 reading at the Tattered Cover Colfax, on the occasion of his fourth novel, The River, being released in paperback.

Westword: You’re coming to read from The River at the Tattered Cover Colfax. How many times have you read at the Tattered Cover now? How has the experience changed over the years?

Peter Heller: I’ve read at the Tattered seven times now. They’ve hosted all my launches – three times for nonfiction books, and then four novels. Every time, it’s a rush – one of the highlights of my life. Hometown crowd, friends and booksellers who love my work and who know the territory. It’s funny: When I read at the Tattered Cover, the audience laughs in all the places I laugh, tear up where I do. Every place has its own sensibilities, and it’s not necessarily that way in other parts of the country. There is just no way to overestimate what it means to an author to have this kind of support, to have such a home.

How has it changed? We all know each other better, and it’s more and more fun.

Kirkus named The River one of the best books of 2019. Can you talk a little bit about where the idea for the book came from? And how do you separate the genesis of an idea from the story that grows naturally from it?

I never seem to get an idea. I came up as a poet, and at the start of a novel, I’m most interested in the music of the language. I write a line whose sound I love and follow it into the next line and the next. But the magic of fiction is that pretty soon I bump into what’s really on my heart, what I’ve been thinking about or [am] concerned with. In The River, I bumped into a story that began when I was seventeen; I was visiting my girlfriend’s farmhouse in rural New Hampshire, and her sisters and mom had a big party. An October night in a little cedar shingled house above a meadow, and a lake with a mountain across the valley. I thought it was paradise. It was there I met a young man with whom I had a strange conversation about a remote canoe expedition he had taken. And I walked away dead certain that on that trip he had killed his wife.

Vintage Contemporaries

I’m fascinated by something you said in an essay you wrote for Powell’s last year – about “old unresolved things” drifting out of the ether of your own past when you’re writing. Do you think that’s what writers are really doing, in the end? Filtering their own experiences – their horrors, their shame, their great loves – through these new characters and circumstance? Sort of writing-as-reanimation?

“Reanimation” is a great word. When I’m writing fiction, I get so immersed. It’s all so real that I feel I’ve been reincarnated into this other life…transmigrated. The narrative is like a river current that I’m riding into new territory, and I come around a bend, and I’m always surprised. Shocked, thrilled, delighted. I write in a coffee shop, and I’ll laugh out loud or have tears dripping off my chin onto the table. I know that other people are probably thinking, “That poor sonofabitch must be going through a bad divorce…” But really I’m just transported and more thrilled than I’ve ever been. And I think it’s such a gift, because I get to have parallel lives. But as you said: Maybe it’s not really brand-new territory. Because we do, as artists, wrestle with our old traumas and losses. And loves. As I write fiction, I encounter them all.

How do you deal with big drama like murder, etc., while not letting the story itself slip into melodrama? Do you find the small moments easier to write than the larger?

Oh, man, I love the small moments – love writing them. And they always exist in the context of a character’s spirit and situation and trajectory. So the act of watching a spider weave her web beside a creek in the evening will have a different feel and heft and meaning depending on who the character is and what she’s going through. The intricate knots, the gleam of sunlight sliding along the silk might trigger a sense of peace or uncontainable joy or the memory of a great loss. So in that way, the big dramatic moments help define the smallest ones. And the small moments anchor the great dramatic ones in a real emotional life, and that keeps them from ever becoming unearned melodrama.

Let’s talk writing habits. I know you’ve said in the past that you’re caffeine-fueled and have a word goal every day. Is there more to it? What else do you need to do in the moment to let your muses know that it’s time to start whispering? And how did you come to develop that as your strategy?

Well, good coffee is certainly a start. Good sleep, good exercise the day before, getting outside. Reading. I kind of treat writing as a serious athlete would her sport, and I do all these things so that I come to the hours of writing in the morning with the very best of myself. But most of all, I find that writing, as all art, is a process of asking a question. To which the novel or story or essay is the answer. And for me, it is of the greatest importance to ask the right source. So I try not to ask the market, or the critics, or my editor, or my readers. I ask God. God as she appears to me, in the sound of wind in trees, a rushing creek, a night dense with stars. If, in your heart, there is nothing more important than this question – a question you probably cannot even articulate- then the answer will come to you out of the dark.

You also do something I tell my students to do all the time: When it’s time to stop writing for the day, stop in the middle of something. A scene, a dialogue, even a line. What’s the writerly effect of that technique? Why does it work so well, and where did you learn it?

I read that Graham Greene wrote 500 words a day every day of his life. And kept a running subtotal in the margin of his notebook, and when he hit word 500 he stopped. In the middle of dialogue, in the middle of a love scene. And I realized that by setting a strict quota he was always stopping in the middle. Of something. And I thought, I don’t do that, and none of my author friends do it, either. We may have our quota of hours or words, but if we get excited about a scene we might write double, triple our daily allotment. But then we’re always ending at a transition, double return, white space. And you come back to white space every day. You might as well start the book over again every morning; it’s tough. So I thought, “Well, I can write a thousand words with good energy, so I’ll do that and write just past it until I’m in the middle of something exciting.” And now I can’t wait to get out of bed and continue what I left. And I’ve garnered all that contained energy. And since writing a novel is a marathon, I’ve helped myself by storing that power. It’s remarkable. The Modified Graham Greene Method. It generates a lot of momentum.

What were those books as a kid that really affected you? I mean the real kids’ stuff, not the high school classics had-to-read-it stuff that you grew an appreciation for. I mean the early words that you remember exciting you?

Pop read to me every night before bed. A lot of poetry. I adored e.e. cummings, and Yeats, believe it or not. Archie and Mehitabel. The rhythms and music. And I loved adventure stories, of course, like Treasure Island and The Hobbit. At thirteen I read Faulkner and was enchanted with the cadence and the way he piled up language to create a dense atmosphere and sense of place.

How has your fiction changed over the years? What’s evolved in your work, do you think, and what’s remained the same? What ideas are you still hammering out in your authorial forge?

Good question. I’m not sure. I know that I am particularly attuned to beauty and loss, to wild places. I think every author’s writing is like a mountain spring, and the water in each tastes differently, has a different color and clarity. And we return again and again to the springs we love. There is a lot of loss in my spring, and an uncontainable love for nature, and a curiosity about how humans address their frailties. Hmm, that answer is completely unsatisfactory – because it might describe most literature. I guess I have no idea. I guess the answer is in the choices made in every word, line by line.

Speaking of your fiction, your debut novel, Dog Stars, was a post-apocalyptic Colorado novel that took place after a flu pandemic. When things like H1N1 and the current coronavirus develop, do you find yourself thinking about that book again?

Oh, yeah! The dying forests, the fires, the pandemic. Gives me goosebumps. I pray we have a much different outcome.

Last question about local writing: favorite literary haunts in Denver? When you want to get out of the house and write, where are the best places to go?

I love to go to the Tattered Cover on Colfax, BookBar on Tennyson, and a few coffee shops which I guess have to remain unnamed, like favorite fishing spots. Also, I love to wander the aisles of Westside Books in Highlands. Since literature is a great ongoing conversation across generations and cultures, it’s good to tune into all those voices. Another great place to work, believe it or not, is Union Station. Go figure.

Peter Heller will read and sign his book The River at the Tattered Cover, 2525 East Colfax Avenuem, at 7 p.m. Wednesday, March 11. Find out more at tatteredcover.com.