The pieces in the show are by some of the most important artists in Mexican art history, as suggested by the mega-famous artist couple name-checked in the title, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. But the exhibit also includes significant works by their contemporaries, including Lola and Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Gunther Gerzso, María Izquierdo and Carlos Mérida.

The bulk of the material in this spectacular exhibit comes from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, the premier selection of modern and contemporary Mexican art still in private hands. The Gelmans, both of whom are now deceased, were among the world’s most significant collectors in the mid-twentieth century. Born in Russia, though later a resident of France, Jacques Gelman met Natasha Zahalka (from Czechoslovakia) while both were in Mexico; they were married there in 1941. As World War II raged in Europe, the Gelmans, who were Jewish, could no longer return to the Old World, so they became Mexican citizens.

Jacques had become fabulously rich as a producer of popular films beginning in the late ’30s, ultimately including the lucrative Cantinflas franchise, allowing the couple to collect art with abandon. They commissioned many portraits of themselves, including a striking one of Jacques by Angel Zárraga and a knockout one depicting a glamorously reclining Natasha by Rivera. They even had Rufino Tomayo do a cubist depiction of the Cantinflas character. Among the only art collectors in Mexico City then, the Gelmans quickly fell in with the artists on the scene, becoming close friends with the likes of Kahlo, Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Diego Rivera, “Portrait of Natasha Gelman,” 1943.

Photo by Gerardo Suter. Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

Hart worked together with the exhibition's designers, Esrawe + Cadena, to turn the Martin and adjacent McCormack galleries on the second floor of the Hamilton Building into a kind of Mexican village of meandering streets, and with different colors defining various parts of the narrative. The time span covered by the exhibit is relatively short — the 1930s to the 1950s — so instead of trying to mount the show historically, Hart chose to develop concentric, if sometimes overlapping, themes with titles like “Circles of Influence” and “Wounded Body."

The exhibit begins with a showstopper, which explains why it’s pretty much been given its own separate gallery. I’m talking about the breathtaking “Calla Lilly Vendor” by Rivera, looking dazzlingly bright against the black walls. The large painting is covered in conventionalized renditions of the white flowers, fitted together like the pieces of a puzzle. In the extreme foreground are two Native flower sellers, seen from the back. Their appearance in the otherwise decorative painting introduces political content, with Rivera championing the plight of the Indigenous peoples of Mexico.

Though Rivera was much more famous than Kahlo during their lifetimes, today his fame is overshadowed by her superstardom, which was sealed in the 1970s by feminist artists and scholars. Her life was one characterized by physical struggles and seemingly endless medical procedures. And her relationship with Rivera was tumultuous and ultimately unhappy. Her work is rich in psychological references to these problems, making it appear much more contemporary than his now seems.

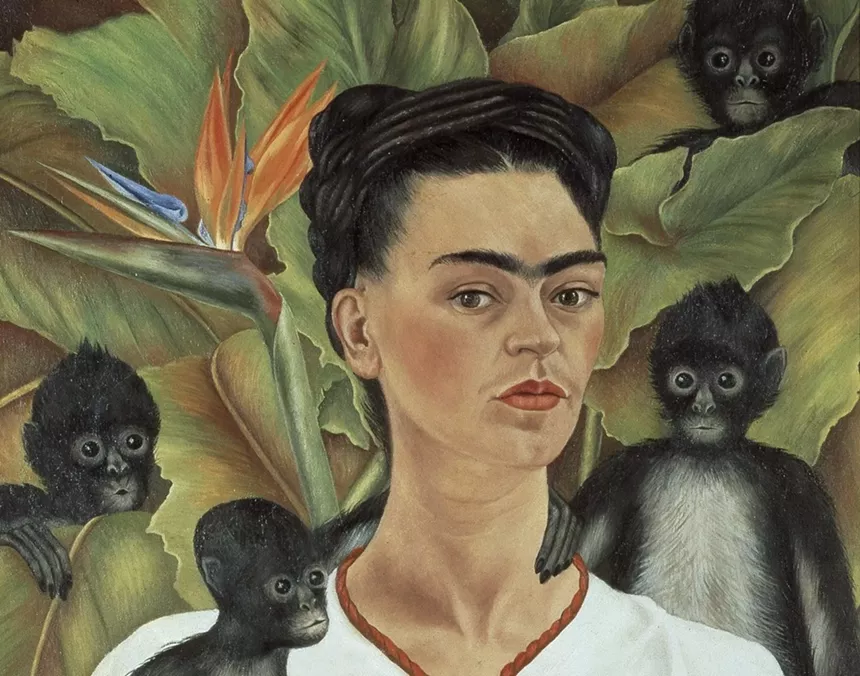

For fans of Kahlo, the show is no disappointment, with over twenty examples of her work including a few well-known masterpieces. Take “Self-Portrait With Monkeys,” in which Kahlo stares at the viewer with a taciturn expression. She is beset by monkeys behind, around and on her, which is disquieting. Even when Kahlo is representational, as she is in this painting, there’s a dreamy surrealism eloquently if silently emitted from the panel. Even more iconic in Kahlo’s oeuvre is “Diego on My Mind”, which is full-blown surrealistic. The totemic Kahlo, wearing a lace headdress, almost like a nun’s wimple, and adorned with twigs falling down from her neck, stares hauntingly at the viewer. But what puts the frisson on top is the portrait of Rivera that runs across her forehead.

Though most of the exhibition is filled out with paintings and drawings, there’s almost a show within a show made up of photos, including some by Guillermo Kahlo, Frida’s father. Many of the photos, by a range of artists, record the historic and modern sites of Mexico, but others depict Kahlo, including one in her hospital bed by Juan Guzman, and another of her by Hector Garcia where she’s laid out in her coffin. These kinds of images reinforce her well-established iconography, which is not so unlike that of a martyred Catholic saint.

At the preview for Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism, DAM director Christoph Heinrich and I commiserated about the unfortunate timing of the show. Even so, he said it was important to go ahead with the opening despite the limitations demanded by the pandemic.

We talked about how in a regular year, a show like this would be guaranteed to be a mob scene, like last year’s Monet show. That, of course, can’t happen right now.

Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism runs through January 24. Tickets from October 25 to November 30 are on sale now (though October is already sold out and November is selling fast) at the Denver Art Museum website. For times between December 1 and the closing day on January 24, tickets will go on sale on November 23 at 10 a.m. Tickets are $20 for members, $26 for non-members and $5 for those ages six to eighteen; admission for children five and under is free.