Wes Magyar

Audio By Carbonatix

Nearly ten years ago, philanthropist Laura Merage created RedLine with the goal of providing studios for artists and exhibition spaces for art. Considering the crunch on artist spaces in Denver right now – the Rhinoceropolis eviction being just the tip of the iceberg – Merage was prescient. At the time she opened RedLine, rent was cheap and the neighborhood around 23rd and Arapahoe streets was down at the heels. Now, with the alternative scene under threat from rising rents and gentrification, a place like RedLine has only become more important. Too bad there aren’t a couple dozen more like it around here.

“Sorry for the late reply,” by Molly Bounds.

Wes Magyar

Membership in RedLine has two levels: one for resource artists, who are given free studios, and one for residents, whose studios are partly subsidized. Members are given a staggered two-year term, with half of them cycling out each year. And once a year, members’ work is showcased in a major exhibition; the current iteration, Nice Work If You Can Get It, is on view now.

Nice Work was put together by guest curator Daisy McGowan, director of the Galleries of Contemporary Art at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs. McGowan began six months ago, asking members to create work that deals with the collision of wanting to make art with the need to make a living. The artists’ responses ranged from the literal to the poetic; some barely addressed the subject, while others were extremely subtle about it.

“Vacant land can be deceptively complicated,” by Ram

Wes Magyar

Subtly was not the way that Sandra Fettingis responded to McGowan’s call; rather, she got downright dramatic. Her installation in the entry gallery, “With or without,” is one of her super-graphic wall murals, the kind you see on buildings all over town – but she has vandalized this one, repeatedly taking an ax to it and cutting away large swaths that are left in piles on the floor. In doing so, Fettingis conveys the impermanence of her work in a rapidly changing city – but it’s still sad to see the piece being destroyed, and I would have liked it better unmolested.

Facing the viewer in the main space is John McEnroe’s “Vigaro,” which covers a wall with shelves arranged in a chaste five-by-five grid. Each shelf holds a single evocative item: small sculptures or found objects like an acrylic rendition of an ax or a plastic funnel, all things McEnroe has assembled over the past 25 years. The work is designed to convey the volume of disparate imagery and ideas flooding the artist, which are all part of the process of arriving at a personal viewpoint.

“With or Without,” by Sandra Fettingis.

Wes Magyar

Adjacent to “Vigaro” are two abstract paintings by Chris Ulrich that have been pierced and stitched. This method reflects another of McGowan’s requests: to convey the difficulty of balancing a personal life and an art career. The two paintings with their rents and repairs represent an organ transplant that the artist’s daughter recently underwent. More upbeat is the installation-as-flea-market-stall by Jennifer Ghormley that’s stocked with T-shirts, tea towels and tote bags printed with politically charged slogans – like the word “nasty” followed by the female symbol, inspired by the recent election.

Around the corner from the Ghormley “shop” is one of the most ambitious pieces in the show, Esther Hernandez’s “This Must Be the Place.” For this tour-de-force installation, Hernandez created a jungle-like garden on the floor, with an inverted living room hanging down from the ceiling. It contrasts the wildness of the imagination with the mildness of the mundane.

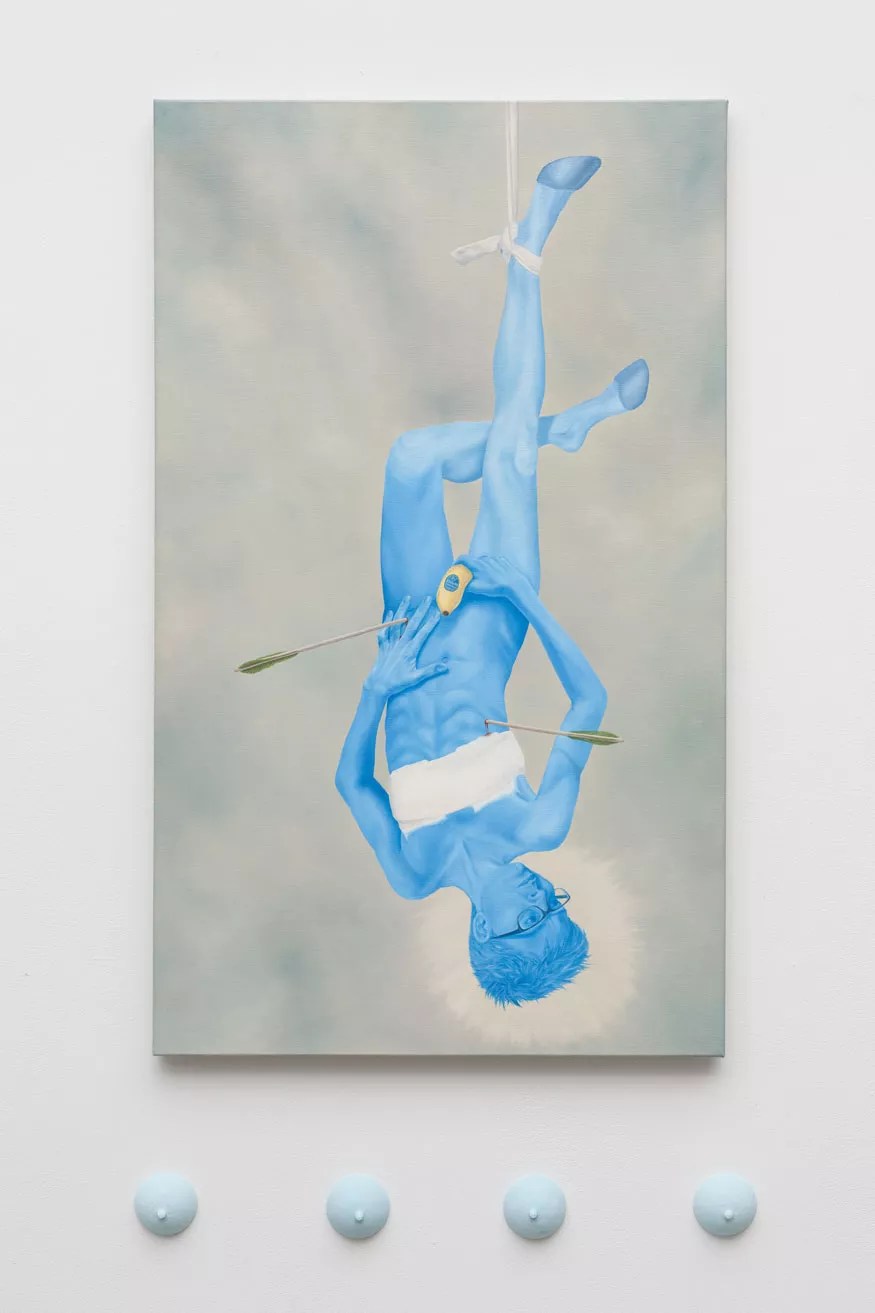

Opposite that installation is Tracy Tomko’s “The Fruiting Body,” an oil-on-canvas self-portrait that fully embraces McGowan’s concept. In the piece, Tomko is trussed up, hanging upside down with her torso punctured by arrows, Á la depictions of Saint Sebastian; her breasts are bound, and on the wall below the painting is a row of cast-sugar breasts. This piece is a direct response to the artist having recently been called “sugar tits” while at work in a factory, and the painting expresses her desire to mask her gender and thus pass as a man. It’s a knockout.

“Landscape,” by Stephanie Kantor.

Wes Magyar

Nearby, a group of seven wall-hung abstract mosaics and a line of shards on the floor make up Stephanie Kantor’s “Landscape,” which encompasses the same kind of creation/destruction dichotomy as Fettingis’s installation. The tiles from which the mosaics have been made, and the shards, are the remains of more than ten monumental vessels Kantor created some years ago and then smashed to make this piece. I found the mosaics beautiful but their origins in the destruction of finished work troubling, and I’m not convinced that irrevocably erasing her own history is necessarily the right way for Kantor to proceed. In fact, I think the piece would be better without that pile of shards on the floor, not to mention the destructive backstory.

Among the only freestanding works in the main space is “Making It,” by Sarah Rockett, a gold-painted handmade ladder accented with rhinestones; the piece conveys the glamorous image of the artist in contrast to the lack of support for art in our dog-eat-dog capitalist world. Another of the freestanding works, Megan Gafford’s “Subatomic Chorus,” is made up of five Geiger counters; it’s meant to be heard, not seen. The counters relentlessly ping, picking up on natural radiation levels in the gallery, providing a nerve-racking soundtrack for the entire show.

Beyond is a spectacular three-piece grouping of works by Mario Zoots called “Bad and Boujee,” which looks something like an urban altarpiece. A large panel in rough-finished concrete touched up with latex and litter is in the center, leaning against the wall. Standing on either side are collage-covered wooden armatures in the shape of silhouettes of rocks. Zoots began his art career as a graffiti tagger, and the phrase “GET A JOB,” spray-painted on the concrete, is a reflection of that – and seemingly the way the piece most directly relates to McGowan’s concepts.

“The Fruiting Body,” by Tracy Tomko.

Wes Magyar

“Vacant Land Can Be Deceptively Complicated,” a wall painting by Ramón Bonilla, is in the niche to the right. Made up of hard-edged intersecting shapes done in black on white, it wraps around three sides of the niche. You can see how it dovetails with his day job at the Denver Urban Renewal Authority, since these shapes could be lot lines, as implied by the title – but it also exemplifies Bonilla’s signature constructivist style. Occupying another niche on the other side is Andrew Huffman’s “Locus-Projection,” an installation made of neon-colored strings stretched in a stack across the corner of the space; like the Zoots and the Bonilla, it only tangentially relates to the organizing theme.

In a show this large, it’s impossible to account for every thoughtful piece – but let me give a last-minute tip of the hat to several more. Sarah Fukami’s appropriated prints of Japanese relocation-camp photos by Ansel Adams are very engaging. George P. Perez’s ruminations on the concept of originality and whether a Seattle artist stole his visual language are more than a little intriguing. The graphite drawings of overspray by Dustin Young are genuinely beautiful and provocative. And finally, the mural by Molly Bounds depicting a woman climbing a fence, with a pair of easel paintings of glasses of water hanging on top, is out of this world.

Curator McGowan had her work cut out for her, since imposing a theme on a pre-existing group is tricky. But the artists working under the RedLine banner are, as a whole, relentlessly able to create pieces worth seeing – and here they’ve created nice work indeed.

Nice Work If You Can Get It , through February 26 at RedLine, 2350 Arapahoe Street, 303-296-4448, redlineart.org.