One of the subjects he often pondered while in medical limbo was parenting, which he writes extensively about in his book Parents Who Don't Do Dishes. And while Melnick certainly covers his fair share of paternal methodologies, a large part of Parents Who Don't Do Dishes is devoted to examining life's simplest philosophies, told in memoir form with a healthy balance of pop-culture references and humor as decoration.

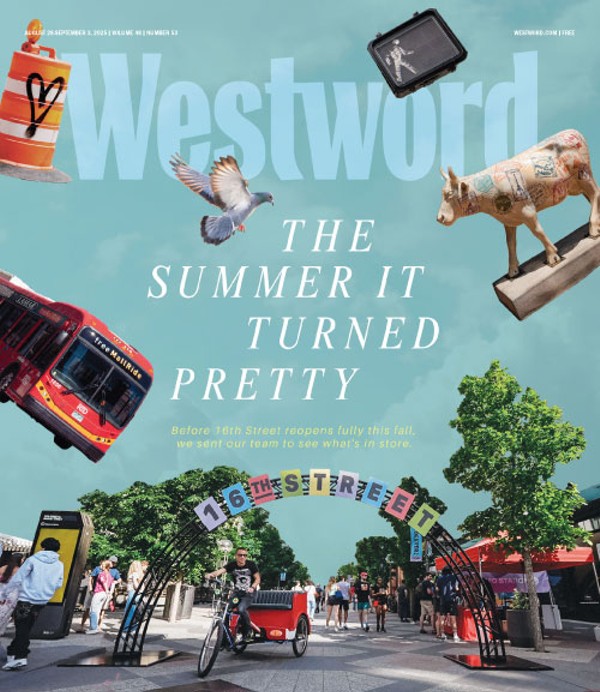

In advance of Melnick's book hitting the shelves at the Tattered Cover this week, Westword caught up with the first-time author to discuss why parents shouldn't do dishes, living in the moment and other random personal philosophies.

See also: - The great debate: Andrew Orvedahl and Jef Otte settle their parenting differences like men - Bad parenting, a school massacre and its aftermath in 'We Need to Talk About Kevin' - U2's 'The Joshua Tree' turns 25

Westword: You write about how, during an argument, your son suggested that you write a book. Was that the moment you realized you wanted to write a book, or did this idea slowly develop over time?

Richard Melnick: Yes, he absolutely did. This was five or six years ago, and it was during the course of a lecture I was giving him -- or rather wisdom I was hoping to impart on him. He said, "Dad, you should really write a book." After the words came out of his mouth, I did start to wonder. Well, actually, I was originally quite pleased with myself for getting that type of reaction out of my speech. [Laughs] But then I did come to wonder if there was a little sarcasm to it. I had been thinking about writing a book for the last thirteen years since I got sick with cancer. Then I kind of blew it off. I'm a slacker and I'm lazy.

My son Josh definitely provided me a nudge about six years ago. Then my ex-girlfriend said that I should write a book of life lessons and work in some recipes as well, because everybody loves my cooking. So a year ago, I figured that was the template for sharing this. It would be a parenting book, and I'd work in some other stuff about practicing immediacy, authenticity and aliveness, which I had learned in particular as a result of having looked into that abyss when I was sick with cancer.

You talk a lot about immediacy in your book. For those who may be unfamiliar with this concept, what does it mean to live with immediacy? How do you do it? And is it possible to combine immediacy with longevity?

Oh, sure. In fact, I think the irony of it is that time slows down when you're practicing immediacy. And when I say immediacy, it's basically my way of saying "living in the moment." It means being hyper-alert and hyper-vigilant to what you're feeling. It's all your sense of touch, taste, smell and so on. I think feeling is your deepest experience of being alive. How do you do that? You first learn to differentiate between thinking and feeling. That was definitely one of the skills I sought to teach my boys when I was scared of my life being taken away from me: learning to notice that voice in your head that is distinct from the feelings you have. The voice in your head typically distracts you from the world of feeling. It works to compete with your deepest experience of being alive. Maybe you're trying to organize and manipulate the next moment instead of allowing it to unfold naturally. Maybe you're labeling the present moment as good or bad. It's just noticing all this chatter in your head. Your natural state should be spacious, alert and peaceful...

You're not gonna make me sound like a crackpot, are you? You gotta tone all this down. This is a lot. [Laughs]

In a way your book reminded me of The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran. It's sort of an archive of different philosophies. One that stood out to me, which you just mentioned above, is the constant battle of feeling vs. thinking. Are those mutually exclusive states of being or can you find a healthy balance between the two?

I think that's what we're all looking for. You just can't let the tail wag the dog. You can't let your thoughts be so habitual that you lose sight of the world of feeling. In a perfect world we'd probably use our brains and our thinking mind 5 percent of the time, just to arrange appointments, be on time and so on. But I suspect we'd be happier if we were more engaged in the world of feeling.

Do you watch Breaking Bad? Can you relate to the main character, Walter White, who also had cancer and was scared for his family and what he'd leave behind? In other words, did your cancer inspire you to write this book in any way?

No, I know I need to watch; I've been hearing about it for years. But I was dealing with cancer about thirteen years ago. It was really the first year or two that it was a major part of my life, day in and day out, in terms of managing the emotional landscape. That's why I weave the story of cancer through the book. I guess what I learned from being sick is to be on fire with gratitude. If you talk to a cancer survivor, they've had their ticket punched. They've looked into that big, deep, dark abyss where there's just no going back. It's humbling. But it comes and goes over the years. When I got sick thirteen years ago, I still had a sense of the possibility of seeing Jackson, my eldest son, graduate from high school. He was entering first grade at that time. And I just remember thinking, "Wow, twelve years down the road -- if only." Having this come to pass, I guess in a way it was a huge motivator because I knew it was now time to totally bear witness to my gratitude. The whole cancer backdrop was strong motivation for me to get it done this year as a tribute to seeing this day come and watching my kid graduate from high school.

You mention god several times in your book, as well as some religious experiences you've had. Do you believe in a higher power?

Well, this is what I refer to in the book as your "Greater Nature." It's being fully accessible in the here and now. It's sort of the doorway to the world of feeling. I had this one type of experience on multiple occasions. When I had this experience, it was like this message was planted into my brain. I don't know if it's a guy with a white beard, but I do believe in some loving omnipotent force. It's some mega-loving force that I couldn't begin to describe. I know that my god, if you want to call it that, is an experiential god. It's not the type of god you need to go to church to be in tune with. But in the book I didn't want to tell anybody what I believe or what they should believe. I just wanted to create some signposts that would allow them to discover their own truth.

You also relate almost everything in your book to the activity of doing dishes. Whether its relationships, moods, maturity -- do you think doing dishes is kind of a microcosm of life?

I suppose. It definitely gives you an opportunity to watch your feelings rise and fall away. You can spend time with yourself and ask what you're feeling at that moment. Is it anger, gratitude, maybe joy bubbling up with the dish soap? It's a great opportunity for kids to learn service and how to work. It's also a great opportunity to learn how to manage your reactivity, if you're not in the mood to do the dishes. But I'm not saying all kids have to do the dishes. My book was really a device for sharing all these lessons. I could have just as easily titled it, Parents Who Don't Vacuum. On this subject, I guess I think kids are more dextrous and intelligent than we give them credit for. It's really a matter of training, accountability and also catching them when they're being good and praising them for doing the things you ask of them.

You have a few funny titles in your book. One of them is called "Shut the Fuck Up," which I found very interesting. Can you briefly describe the thesis of this chapter in regards to parenting and the psychology behind it?

[Laughs.] It's part of the grand bargain that I outline in the book. It's about parents recognizing their kids' sovereignty. Kids offer tribute in exchange for having their sovereignty acknowledged and respected. As a parent, part of acknowledging that your kid is an independent being is learning to manage your own reactivity. In the book I write, "I agonized over including this phrase as I know it will offend some kindly readers, though it seems to me that it's only this kind of vulgarity that adequately speaks to the obscene practice of bossing your kid around as if you knew what your kid needs to do or think. Micro-managing your kid is deeply offensive and a huge spiritual, emotional and practical mistake." So yeah, it's vulgar, but I think those words are shocking. I wanted to shock the readers into taking accountability. I think it needed to be in there.

You also mention having dreams that come true in real life. I too have experienced this phenomenon. Do you have an explanation for this? What do you make of these clairvoyant dreams?

Well, my explanation is that time is non-linear. If you want my real bias, it's that we're everywhere, always. Form is an illusion and time is an illusion. There's an unmanifested world. Some people call it consciousness or your spirit or your soul. I call it your Greater Nature. Whatever that is, it doesn't die when your body is gone. This is my belief. This energy is not defined by your body. It's eternal. It's everywhere and it's always there. If you have that sort of foundation or belief system, then it's easy to explain how you may have had a dream on Tuesday that came true on Thursday, or five years later, or even 25 years later. So it kind of makes sense that it's all jumbled up. It's not linear. It's all happening at once. I don't know. I don't have any proof of it. Off the record, I don't know what the hell I'm talking about. [Laughs.] I represent in the book that I don't normally talk like this.

So, do you want me to leave that last part out?

You mean the fact that I don't know what in the hell I'm talking about?

Yes. Well, I think it's funny because to me that's what the book was all about. It's a huge balance between lightheartedness and some pretty deep stuff. That was the strength of your writing, in my opinion.

Well, thank you. I appreciate it. That's really what I was going for. Okay, so you can include it. Whatever. You know, I'm starting down this path of doing interviews and it's been kind of interesting for me because I've been kind of stiff. But now I'm realizing nobody is gonna buy my book if I just prattle on. I just have to be myself and let the chips fall where they may.

But that's definitely the attitude you need to have. Because then when people actually do buy your book, you'll be pleasantly surprised -- which is another thing you talk about in your book. Can you expand on the idea of pleasant surprises and what you think they mean?

It's like a beautiful stolen moment for me. Pleasant surprises are why you get up in the morning. [Laughs.] That's kind of a stupid answer. Hold on, let me find the section where I wrote this. Okay, so the idea of pleasant surprises is that they can happen when you're participating radically in the truth of what you're feeling now. I think it's that act that allows for some transformation. As opposed to fearing the next moment, you're in tune with the now. It might be pleasant, it even might be unpleasant, but either way you're willing to go with it. Here's the point: You can't selectively feel. The degree to which you're willing to feel pain is the same degree to which you're willing to feel pleasure. When you participate in the truth of what you're feeling, you allow for pleasant surprises. It also allows for painful surprises. But at least you're real. At least you're keeping it real. That's what authenticity is all about. Music is obviously a big part of your life. What's the most spiritual experience you've ever had while listening to music?

I feel like whenever I'm really engaged with the music that's playing, it's always a spiritual experience. There's something about the music that quiets my mind. It's all-consuming. I just let my mind go with the melody and am consumed by the silence of my mind. When I was sick there was something about music that was especially healing for me. I think there's always a song for you, whether you're happy or sad.

So, do you have a certain favorite song of all time?

There's a couple. U2's "Mothers of the Disappeared" is definitely one of them. I think all of Joshua Tree, actually. That's an album that just really holds up. And it's not a coincidence I'm so fond of it. because it came out just after my best friend Marco was killed. It was so especially healing for me and definitely spurred a lot of tears. And then lately I'm listening to a lot of Martha Scanlan and Gillian Welch. In particular there's a Reeltime Travelers song, which was Martha Scanlan's old band, and it's a song she wrote called "Higher Rock." It has these verses that are deeply moving. I'd actually like to meet Martha Scanlan and ask her about this song. But definitely "Mothers of the Disappeared." It just puts me in such a reverential mindset and state of being. Also, I've been listening to a lot of Townes Van Zandt over the last few years and I feel he's the best songwriter that America has produced. I don't know, he just made sure all his songs worked on paper as well as musically. His writing was just so strong. His words packed so much emotion. I really think he's up there in the pantheon with Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen as far as gifted songwriters go.

You've lived everywhere from Denver to New York, to California and Crested Butte. What do you prefer now, big cities or small towns, and why?

Right now I have the best of both worlds. I'm able to get to New York City frequently because I have friends there and do some business there, yet I enjoy all the benefits of a small-town life, too. I heard a quote from Mother Teresa, maybe thirty years ago, and she said something along the lines of, "bloom where you're planted." I thought that was great advice.

Cooking is another huge part of your life. You even have recipes in the tail end of your book. So, million-dollar question: If you could order or cook anything in the world, what would you want to eat for your last meal?

Wow. Oh man. I guess it would be beet chips, asparagus vinaigrette and my strawberry pineapple ginger beet smoothie. And maybe some of Brian's Potato Salad, which you can find in the book. [Laughs.] You know what? Here's the real answer: My final meal would be whatever local, non-genetically modified food was available. That's really what I want to eat.

Is there anything else you'd like to say regarding this book or life in general?

One of the most important things I wanted my kids to learn was to develop a playful relationship with disturbance. You can't chose your life to be all Skittles and unicorns. You can't just selectively feel the fun stuff. You have to be willing to feel whatever comes up. I wanted my kids to learn to be willing to feel anything. If it was anger or anxiety or whatever -- I didn't want them to have to find someone or something to blame for the way they feel. I wanted them to learn how it's a fantasy that life should be free of disturbance. Don't organize around avoiding disturbance in your life, just allow it to happen when it comes. This might be something outside or an internal conflict. It might just be contradictory feelings. If you want to really get honest with yourself, you have to ask if you want to even be alive or not. I wanted my kids to be willing to appreciate being alive. I think once you have this understanding, this foundation, it allows you to have a more playful relationship with whatever life brings. And the paradox of it all is that the more you're willing to experience pain, to that same degree you'll be able to experience pleasure. You can purchase Parents Who Don't Do Dishes at the Tattered Cover, but you can also find the book online at Amazon.com and for a discounted price of $10 at Melnick's website.

Follow @WestwordCulture