TaraShea Nesbit

Audio By Carbonatix

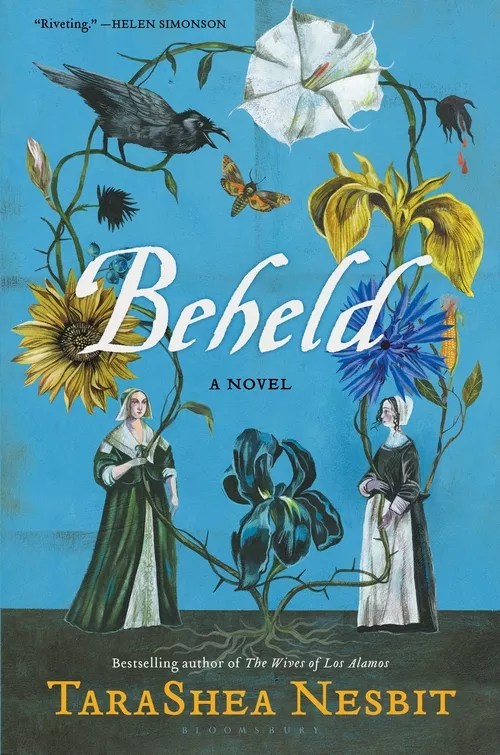

TaraShea Nesbit is a Colorado writer who hit big with her first historical novel, The Wives of Los Alamos; she was planning to launch her followup, Beheld, this week at the Tattered Cover, but that was canceled because of the national coronavirus emergency. So she’s gone digital; instead, she’s doing a virtual book launch on Facebook Live on Tuesday, March 17, at 1 p.m., where she’ll “talk about the novel, take questions from viewers, and likely be interrupted by a toddler waking from his nap.”

We’d interviewed Nesbit before the pandemic hit, long before the cancellation of the live reading and the invention of the digital one, and perhaps the conversation will inspire you to pick up a copy to read – or tune in – while you socially distance yourself.

You were originally planning to launch Beheld at the Tattered Cover in more normal times; what’s it like to come back to Colorado to read your work?

Oh, my heart, Colorado, I love you. I love the beady red eyes of the blue horse as one exits the airport, I love the white-tipped mountains in the distance, the too-bright sun, and that muddy hiking boots are in many occasions perfectly acceptable work wear. I am a faculty mentor in Regis University’s Mile-High MFA program, and my husband works remotely for a company in Boulder, so thankfully we get back to Colorado at least once a year, and I still get to feel tethered here. I love the strong literary and arts community of the Front Range. I love that one feels inspired to be outdoors year-round and care for the natural world. Coming back feels like returning to my chosen home.

Bloomsbury

Your first book, The Wives of Los Alamos, was about the spouses of scientists working on the atomic bomb; this new book, Beheld, is a retelling of the Plymouth Colony and its first murder, as told through the voices of two women from very different circumstances. Do you consider that your niche, the female perspective on history too rarely told?

It seems to have found me. I had early energy to fight against injustice toward women – like in fifth grade, girls were not allowed to play football with the boys at recess, so I drafted a petition, organized the other girls, and we got a great number of signatures. But at the meeting with the principal, he said, “We aren’t changing the policy.” I’d had my first encounter with the limits of my work against authority.

In my family lineage, women have been resilient figures who are also not given their due, and I am a woman, so I am attentive to how woman are treated and perceived.

But I’d say I’m interested in perspectives that have an element of misunderstanding to them and about turning points in American history. I’m curious about how to be a good person in the world, good to one another, without taking up too much room. I’m interested in how power operates.

What drew you back to the Plymouth Colony and those early days of American history?

The first thing was the exciting oddity of language and that moment in scientific history. I loved “God’s back parts” as a phrase and an idea – that God is present even when we cannot see evidence of him. I loved thinking about a time in women’s lives when they birthed children with midwives and other women. I liked imagining how one would talk about a person who was acting angry or impulsive as having an imbalance of yellow bile. I loved how they were still thinking about signs – everything could be a sign.

I didn’t particularly want to write about all the infant loss that was also present at the time, but that emerged, and eerily coincided with my own daughter’s passing, which was a coincidence I wish on no writer ever.

Plymouth is a city that has branded itself as “America’s home town.” We can question that label, but the story of religious freedom seekers and ancestor worship looms. I started to see things Bradford left out in his narrative, and I became haunted by the ghost of his first wife. I started to see entryways into the story and saw parallels between crime in the 1630s and contemporary incarceration, as well as between separatist puritans’ xenophobia and current immigration policies. But of course those were ideas, and I didn’t start out with ideas fully in mind; I just was haunted by this woman and started writing what voices started to talk to me. Then I became drawn to this first murder trail in Plymouth, and I started to see how the characters could have that day as a central focusing event. Characters have their own ideas on the page, which is how the love stories and survivor’s guilt emerged.

And what about historical fiction in general really entices you? What about it makes the form so popular with readers, do you think?

I admire novels that seek to add to our imagination about history by creating compelling characters from people we don’t have much information about, who have been silenced or under-listened to.

I’m drawn to nonfiction first – people’s account of their lives and how that has been shaped by the times and environments in which they lived. I’m interested in poetry’s estrangement of language as a method, also, for attunement. And for a long time I could not read most fiction at all, any fiction, because the costumes and props and backdrops of the artifice of fiction seemed to obfuscate honesty to me. I wanted refinement of word choice and aesthetic appreciation. But I see now I was just not reading enough fiction by women and writers of color and not enough non-linear narrative fiction. Then I read Audre Lorde, James Baldwin, Grace Paley, James Agee, Leslie Marmon Silko, Gish Jen, Kent Haruf, and I fell in love with prose. Fiction often uses a populist language, and I appreciate that. It wants to convey without being particularly coy.

I think readers interested in history and historical fiction are, as a group, attentive to how we are all interconnected in the present and in the past. It feels like an act of generosity and selflessness to look outward into the world, and historical fiction can do that. Fiction set in the past, if done well, does what fiction set in the present does – commenting on this time we live in, but also giving this time a historical context.

So what’s your process for writing about a historic era? How long does the research take you, and how much does what you discover in the research inform the creative process?

The process of writing these two books was so different! Different projects require different processes. With The Wives of Los Alamos, I had been researching nuclear waste and radioactive animal farms and atomic history for a few years before I got the idea to write the novel, but I had all of this background information rattling around in my head. I had ingested it enough to not feel quite so stiff about the facts, details, and verifiable and non-verifiable things. Then I wrote the first draft in a flurry over winter break while living in a sweet loft in the Golden Triangle in Denver. We had this view from about eight stories up that looked out to the foothills and also across into the city, and I felt like I was writing in the clouds.

With Beheld, I was fascinated by the time period, but also intimidated by all that I did not know. I resisted writing it for quite some time. I didn’t know if they used forks! How could I possibly be so bold as to imagine their interior lives? But through a zillion conversations with historians, scholars, knowledge holders, novelists, friends and translators over five years, I began to see conflicting evidence. Two or more narrative accounts of the same events could reach vastly different conclusions. That started to free me up to write. And I did that writing in a little house in Boulder in the early-morning hours before the baby woke, and in a small town in Ohio – sneaking it in most of the time except for one really generative semester I had off from teaching for pre-tenure sabbatical.

As for the actual research: I took several trips to Massachusetts and lived there for a summer while I was on a fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society. I visited many museums. I studied maps and reviewed court records from Amsterdam and Plymouth. I was writing throughout the research, and rewriting. I birthed children and took them with me to living-history museums and to the beach. I had many conversations over five years’ time. I came to see that what I’m doing as a novelist is not historical veracity, which, well, is only partially a thing. What I’m doing as a novelist is having a conversation with the past. I’m having a conversation with how the past has been narrated previously by people in positions of power, and I’m having a conversation about the present through the past and thinking about the interconnectedness.

How do you balance the history with the fiction? Is too much history detrimental to the fiction, and vice versa?

It definitely depends. With early-American history, I worked a lot from inference, and at some points I loosened timelines to enable another conversation to occur or theme to emerge that I saw present, but wasn’t able to bring up unless I compressed time or created a composite character. Zadie Smith talks about two kinds of writers in her essay “That Crafty Feeling”: macro-planners and micro-managers. The micro-managers, of which I have a tendency toward, are vulnerable to creating beautifully wallpapered staircases that lead to nowhere. She’s talking about crafting a novel, but I think of it as crafting a novel about anything that requires significant research. Historical period details are akin to wallpaper. Beautiful – but without story and character, they will lead to nowhere.

Anachronism must be one of the things you look at in editing. Do you tend to still see that popping up in your writing in the early going, or have you trained yourself to think in terms of that era such that you don’t risk such small but important errors?

Such a great question. I have anachronisms and work to avoid some, but it gets more difficult, particularly the further one goes backward in time. A complete 1630s language, for instance, would be utterly alienating to many readers. I think of it like a modern translation. Not Dante’s Inferno, but Mary Jo Bang’s Inferno. I hope I get enough into the headspace and research that I get a bit more right than wrong, but overall I’m thinking in terms of how a novel with a historical setting is trying to re-evaluate that time by looking at people who have not been given enough attention while also being a novel about the present.

I researched Beheld for five or six years, and then I tried to forgive myself for my errors with the knowledge that I’m marking two moments in time: 1630 and 2020.

What’s an era that you haven’t yet written about but want to?

I think the yellow journalism and competition between New York and California newspapers in the late 1800s is fascinating. I have an entry point in mind, but I think there will be one book between Beheld and that one.

Can you talk a little bit about your time spent in Boulder? How did your education there and your time in Colorado help develop you as the writer you are today?

I wrote both of my books in Colorado. I moved to Denver from Tacoma to get a Ph.D. in creative writing and literature at the University of Denver. The community of writers and scholars on the Front Range is vast and inspiring: Lighthouse! The Gathering Place’s writing circles! Counterpath! BookBar! The Tattered Cover! The Boulder Book Store! Old Firehouse Books! A zillion readings and universities!

When I arrived in Denver, I’d never written a fictional story and I had never taken a fiction workshop. By the time I left Colorado I’d published my first novel and several essays and had a draft of my second novel. While in Colorado, I learned how to write stories, how to train for a half-marathon, how to hike with friends, how to teach, how to get an academic job, how to be diligent about reapplying sunscreen.

You teach at Ohio’s Miami University these days. What do you love about Ohio, and what do you miss most about Colorado?

I have an essay coming out in Lit Hub on March18 that is about this exact topic, especially about returning to Ohio. I lived my first 23 years in Ohio, in the Miami Valley, and the best thing about being in Ohio, aside from having a job that I feel very grateful about, is that I am near my family. It also means we are not near my husband’s family, which is a difficult trade-off – he’s from northern Nevada – but I love that our son and daughter are growing up with extended family around.

I miss certain summer weekends in Colorado, hosting a dinner party with a handful of friends on the back porch of our tear-down bungalow as the sun set behind the foothills and the bug lights turned on, and we could hear the coyotes howling but our laughter was louder, and the air was crisp and there were no mosquitos, and I’d fall asleep reading a book I picked up at the Boulder Book Store or the Tattered Cover, and in the morning we’d walk toward Mt. Sanitas and stop to sit on a bench and look down upon our small but not insignificant life.

TaraShea Nesbit’s new book, Beheld, is available online at the Tattered Cover website.