The second bullet never came. The shooter ran.

Brad stumbled toward his friends, who were up the street outside Pierre's Supper Club, near 22nd and Downing. One was arguing with a police officer from the gang unit who knew Brad, an original gangster with East Side Trey Deuce Gangstas, by his first name.

Brad told his friends that he'd been shot, but they thought he was joking -- until more shots rang out. The officer wanted him to lie down and wait for an ambulance, but his friends loaded him into a minivan and headed for nearby St. Luke's Hospital. He tried to stay calm and alert on the ride. He kept asking the driver what street they were on, how much further it was to the hospital. Growing up gangster, Brad had been with friends who'd taken bullets. And being shot at was nothing new; it comes with the territory. But this was the first time he'd been hit.

Doctors said the bullet had bounced off Brad's hip bone and ricocheted through his bladder, scraping his colon along the way. He was transferred to Denver Health, where the bullet was removed and Brad was stapled shut about thirty times.

People who hadn't seen Brad in years popped up to visit. Brad had always been the kind of guy who visited friends when they were in the hospital; now they came to him. Relatives stopped by. And the school where he works sent flowers.

Brad spent five days in the hospital after the August 19 shooting, and between visits, he had plenty of time to think. He'd already been to gangster destination number one: prison. He'd been in and out of jail since he'd turned eighteen, and he'd done five months of a four-year sentence for drug charges in Cañon City before his sentence was reconsidered and he was released on probation five years ago. Now here he was at gangster destination number two: the hospital bed. Gangster destination number three is final: There's no coming back from the grave.

"Every gangsta got his day," Brad says. "We either gonna be shot, stabbed or do your time in prison. We all know that. There's something in store for every last one of us."

Today Brad is 34 years old. He has a family, and a future with a job he loves. The homeboy's a homeowner. A substantial citizen.

Some of that substance made the difference between life and death. Doctors told him that if he hadn't recently bulked up to 215 pounds, the bullet might have torn right through him. Then his wife would have been a widow and his two daughters would have been fatherless. And the 167 inner-city kids he helps after school at the Open Door Youth Gang Alternatives program would have lost both a friend and a mentor, one who knew what he was talking about.

"I was just telling the kids the other day, 'Don't join a gang, because everything you do in a gang eventually comes back to haunt you. And if you ever stop banging, that doesn't mean the gangstas you did things to are going to forgive and forget,'" Brad says.

He knows who shot him. He thinks the young black man took aim for one of two reasons: He feared Brad, or he was intent on taking out a Trey Deuce. Or both.

Just as there are three gangster destinations, Brad knows of four ways to deal with someone who wants him dead.

The first option -- going to the police -- isn't an option. Brad has no faith in the justice system. And even if he did, he lives (and could die) by the code of the street: no snitching.

Second, Brad could order his shooter murdered as easily as you could order a pizza. He's at the top of the power pyramid in his gang, a position he earned over the years. All the younger gangsters in his hood are trying to come up, and they'd love to put in work for the OG. But Brad is a man who takes pride in doing his own dirt. And he says he'd never order someone killed, because he's never killed anyone.

That's the third option: murdering the man himself.

"If I want him, I know where to go get him," Brad says. "It's not necessary that I even need to get him; I could get his buddy. That's what they did to me."

Or Brad could do nothing and leave the younger gangster's fate to the street, which would inevitably lead him to one of the three unavoidable gangster destinations.

Just like Brad.

The Curtis Park projects were already tough when Brad was growing up. Every night, there were fights, gunshots, drug deals, stabbings, sometimes murder.

He was about twelve when a trucker parked a trailer filled with thousands of cans of tuna at Larimer and 33rd. Brad and a couple of cousins broke in, grabbed as much tuna as they could and started handing it out in the hood. They ran back for more, and sometime during the second distribution round figured out that they could make some money selling the canned fish. So they returned to the trailer. But this time, Brad got caught.

This was his first run-in with the cops. They thought he was just a punk kid, bought him a burger and fries. The trucker let him keep the tuna -- and Brad's father made sure he ate every last bit of it.

But if life in the projects was tough in the early '80s, it was about to get a lot tougher. By 1985, the Denver police were noticing a lot of young gang members running these streets. Gangsters like then-fourteen-year-old Brad Braxton. The "3" and the "2" tattooed on his neck and right hand stand for East Side Trey Deuce Gangstas.

Like the ink, Trey Deuce is for life.

Trey Deuce, a homegrown set, claimed the hood along 32nd from Lawrence to Downing. From Downing to Colorado, kids were wearing blue rags and calling themselves Eastside Rollin' 30s Crips; this gang stretched back to friends and relatives who were Crips in California. Crips' most notorious enemies are Bloods, and a Bloods set with links to California started claiming the streets east of Colorado to Quebec.

Crips wear blue, Bloods wear red, Trey Deuce Gangstas wear black and gray. The mid- to late '80s were all about gangbanging over colors and the territory that came with them. Denver police were finding more and more guns on these kids in blue and red, kids who spoke a slang the cops often didn't understand.

The Reverend Leon Kelly started cruising the streets in 1984, reaching out to as many gang members as he could. A former drug dealer and ex-con who'd done three years for robbery, "Rev" spoke the gangsters' language. He tried to convince the city that it had a problem, but felt the administration of Federico Peña downplayed the growing gang activity in order to project a positive image of Denver.

Kelly knew the first OGs in Trey Deuce -- Brad's older brother, a cousin and three other gangsters -- and has been part of Brad's life for more than twenty years. The two are close. Brad went with Rev and rival gangsters to gang summits -- meetings designed to create truces between rival gangs across the country -- in Miami and Detroit in the late 1980s and met the likes of Don King, Mike Tyson and the Reverend Jesse Jackson. But he passed on a trip to Watts. "The gangstas in California started this shit," he says.

More crack started flowing into Denver as word spread that there was money to be made on this city's streets. The crack was pumped through a pipeline created by the gangs, and the profits siphoned back out to the same Crips and Bloods in California. "The Big Easy," Kelly remembers them calling this town.

Brad bounced around between Kennedy, George Washington and Manual high schools, playing football and selling joints to the white boys along the way, sometimes collecting a hundred bucks a day. But the real money was in crack, so he dropped out of school and hit the block. Someone fronted him a quarter-ounce of crack worth about $250. Brad hustled, and walked away with $500 in profit. Then he got another quarter-ounce, and another. He sat on his profits until he stacked enough money to buy an ounce of his own for about $1,000.

Crack upped the stakes for Denver's gangs -- and the violence.

In 1989, Brad's OG cousin was standing on the corner of 27th and Arapahoe when some Bloods from a Mexican set came to the hood, seeking revenge. They shot him dead. The killers were never found.

As other Trey Deuce OGs, including Brad's brother, went to prison, it was up to Brad to recruit new members for the set. "Whoever was down, as long as you had heart," he remembers. He found several young black men and a couple of Latinos who seemed fit for duty. Brad told them they could end up dead, in jail or in a wheelchair -- but those who were willing to risk it in order to be Trey Deuce Gangstas would always have homies at their back and money in their pockets.

By the early '90s, Trey Deuce, Rollin' 30s Crips and Trey-Treys, a second generation of the Rollin' 30s that also identified with Crips, developed a united front and relaxed borders so that members could do deals in each other's territories. Although Brad kept ties with Bloods -- and once got arrested for gambling while shooting dice with some Bloods -- he and the rest of Trey Deuce did more business with Crips. And there was plenty of business to do.

A gangster with a video camera captured the scene in City Park in '91 or '92. It was like a Dr. Dre video. Dozens of young blacks gathered to barbecue and drink beer: Crips in blue and Trey Deuces in black and gray, sipping 40s, side by side. Gang signs flew out of 1964 Impalas and other classic American models hooked up with banging stereo systems. The rides sat on gold spokes, and switches inside set the cars bouncing off the ground or rolling on three wheels.

A few segments of the video focused on the aftermath of drive-by shootings, which were becoming increasingly common.

The crack rocks flew out of Brad's pocket. He moved his way from ounces to "half-chickens," or half a kilo, then started moving whole chickens, quickly making up to $5,000 on each. Trey Deuce was doing so well, Brad remembers, that the set rented several townhouses, selling different dollar amounts of crack out of each to keep traffic down. Crackheads would bring in gold, guns, liquor, stereo equipment, food and food stamps to get their rock. But there was no crack smoking allowed on the premises.

Brad was ballin'. By now, he and his wife had a daughter, and they lived in a rented house at 34th Avenue and Race Street. He kept hundred-dollar bills in rubber-banded stacks of ten in his dresser. The back yard was like a car lot. Brad drove a different car almost every day of the week and tried to match his outfits to his rides. The 1979 El Camino SS sitting on gold Dayton spokes was his baby; he also went through two Chevy Caprices, a Pontiac Grand Am and a 1965 Impala. He used a 1975 Colt with a paint job like the car on Starsky and Hutch as his "hooptie," to transport drugs around town. Brad would blast Mexican music out of the ride and wear a big hat to disguise his identity. Sometimes he'd put on big butterfly glasses and a purple hat with flowers so that cops would think a woman was driving.

Trey Deuce's united front with Crips fell apart in the mid-'90s, but there was still plenty of money to go around for both gangs.

One day in 1997, Brad rolled up in his hooptie to deliver 9.5 ounces of powder cocaine -- and the police swarmed him. It wasn't cheap, but a good lawyer got Brad ninety days in jail and a deferred judgment. When he got out, he went into "hibernation," he says, lying low while he had workers in the hood slanging rocks for him. But one of Brad's workers lost nine ounces of rock to the police, and another fled with five and a half ounces. Brad's fortune shrank from an estimated $150,000 to $20,000. To get back to the top, he had to get back on the block.

In February 1999, Brad sold crack to an undercover cop in Five Points. It was at least his ninth arrest in Denver -- for drug offenses, weapons violations, assault charges -- since 1989. He left his family with $8,000 and went to jail, then prison.

Brad's oldest daughter visited him once in prison, but that was all she could take.

When Brad got out in May 2000, he went home to his family. That day, his cousins came to take him to a barbecue; they were driving a Cadillac and a Mercedes. They stopped to wash the cars, and one cousin went over to the gas station to make a drug deal. Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms agents stormed the scene. They let everybody go but the cousin who'd sold the sack, and Brad, whom they accused of being a scout for the drug deal.

Brad demanded to speak with officers in the gang unit who knew him. He'd been free less than 24 hours, had just $18 on him, and insisted he wasn't involved. The cops believed him, and he was set free.

Brad went back to the block.

He started slanging on a new corner, at 25th and Clarkson. One day he'd made $2,000 in just five hours, he remembers, when a cousin who'd recently joined the Navy rolled up. Brad told his boys to shut down the block and took off to visit with his cousin. As they drove away, he got a call that cops had raided the block.

Brad spent the $2,000 on a 1987 Monte Carlo and quit the crack game for good.

Gangs fund their organizations by slanging crack. To increase profits, they kill rival gangsters and steal their sacks or their territory. The shootings and murders are often viewed as drug-related by authorities, but they're all gang-related, too.

A few high-profile crimes earned 1993 the "Summer of Violence" tag in Denver, but there were no more gang murders that year than there were the year before, or have been in many of the years since. While the DPD counts five gang-related homicides this year (see story, page 28), Kelly says the number is closer to thirty. And the district attorney's office has prosecuted a dozen.

Tim Twining, chief deputy district attorney, supervises the gang unit. He worked with the gang unit for six years before it was disbanded and has been its supervisor since it was resurrected three years ago. "I'm convinced that we have more gang members in our community today than we did ten years ago," he says. "No doubt in my mind."

The days of gangsters in colors blatantly standing on the corner selling rock have faded as gang members have learned to keep more low-key. Today it's more about money than gang glory, Twining says, and kids who sign up for a street gang are committing to a life of crime.

Gangs these days have more sophisticated weaponry and less fear of the consequences. The crimes may be less colorful, he adds, but there's no question that this city is in the midst of a full-scale gang war.

Brad's nephew is part of the next generation rising through the gang ranks, a group that shows less restraint than was shown in Brad's day. A dozen years ago, the guns didn't come out until after an ass-whuppin' or two -- Brad's nickname coming up was "Scrap," and he earned it -- but these gangstas are quicker on the trigger. "We weren't ready to rob and kill for money," Brad says.

One day this summer, two rival gang members ran up on Brad's nephew in Five Points. He resisted, but one of the guys took out a gun and shoved it in his face hard enough to split his lip. They took his cell phone and $3 -- but he managed to keep a wad of cash hidden in his pocket.

On August 19, several weeks after his nephew got jacked, Brad went to Pierre's for a friend's bachelor party. A couple hundred people were gathered outside the club, including a bunch of Brad's old homies, who were drinking beers and reminiscing. The wedding was scheduled for the next day, and Brad hadn't seen the groom for more than a year. A DPD gang-unit officer who was in the crowd recognized him. "We aren't going to have any problems tonight, are we, Brad?" he asked.

"Hell, no," Brad told him. "This is a bachelor party."

Brad headed down the street to the liquor store for more beer and some smokes. The kid who'd jacked his nephew walked up. He'd come up to Brad a few weeks before at Pierre's, said he guessed that Brad had heard what he'd done. Brad had, and would have loved to have given him a whuppin' right there but gave him a pass instead.

Now he gave him another pass. "Just go on about your business, cuz," Brad said. "You ain't gonna fight, nigga; all you gonna do is shoot. Go ahead and get on."

As he left the store, Brad saw the kid coming across the street with one glove on. Brad thought he'd gotten a couple of drinks in him and had gained some heart, and was now ready to scrap. But instead of putting on another glove, the kid pulled out a .45-caliber pistol. Brad heard a pop. He struggled to keep his balance and waited for the next shot to end his life.

"Department of Corrections," Reverend Kelly said to the guard in the hospital elevator.

"What do you know about the Department of Corrections?" the guard asked.

"I know I'm trying to keep my kids out of there," Kelly replied.

Kelly knows a lot more than that. A preacher's kid, he grew up in Denver, graduated from the University of Colorado in 1976, played basketball in a semi-pro league and developed a cocaine habit. Two years later, he quit playing ball and started selling drugs. He quickly worked his way up to a penthouse in Brooks Towers but was brought down in 1979, when he was sentenced to five to eight years for aggravated robbery.

The sentencing judge pulled Kelly aside. He told him he saw something special in him and had sentenced him to prison time in order to save his life.

When Kelly was released from prison in 1981, the judge was one of the first people he went to see, so that the ex-con could thank him. Kelly worked random jobs for a few years, then became an ordained minister in '84 and started reaching out to gangs.

At 6'5" and 230 pounds, Kelly's a towering presence, with dark skin and cornrows. "God's G," as it says on the back of his truck, has seen hundreds of kids buried, many of whom he'd known since before they were gangsters. He was there when Brad's cousin was murdered, when Brad's brother went to prison and when Brad went to prison. This summer, he almost had to bury Brad. Instead, he went to visit him in the hospital.

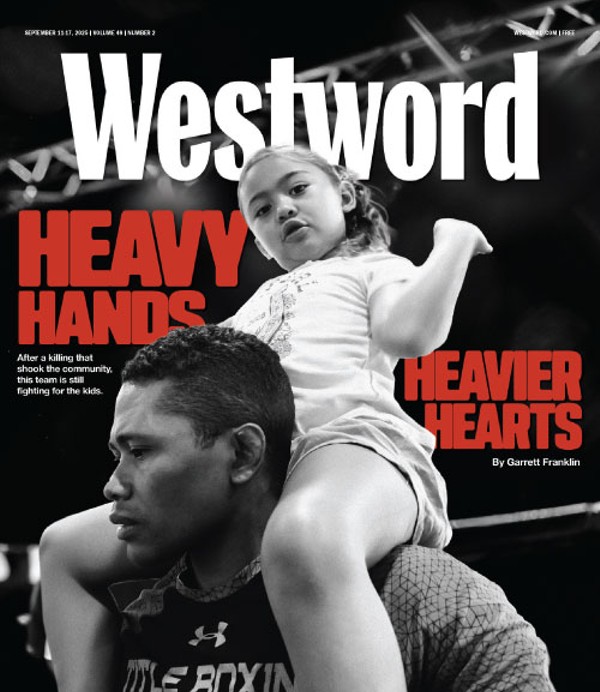

Kelly's the executive director of Open Door Youth Gang Alternatives, a group he founded that holds meetings with concerned parents, hosts workshops and community meetings, acts as a liaison and sometimes a buffer between police and gangs, and runs an after-school program at Wyatt-Edison Charter School. Although Brad has been hanging with Kelly off and on for the twenty years that Open Door has run such programs, it wasn't until 2004 that he got a paying job with him at Wyatt. The after-school program there is designed to give kids discipline and structure. They do their homework, play, and develop relationships with staffers who try to teach them about the consequences of gangbanging and drug-dealing so that the kids don't have to learn it the hard way.

Brad has had other legit jobs in his life. He's a certified forklift operator and had gigs at Coca-Cola, Coors Field, a trucking company in Longmont, a Denver warehouse and a few other places. But he's never kept another job as long as he's been with Open Door.

"What people don't understand is that the dope game is an alternative for people like me," Brad says. "It's just the way of the world."

Brad was shot the weekend before Wyatt's program kicked off for the year.

Kelly doesn't condone the violence or drug-dealing, but he understands it. "To them, this is their family, their sense of security, their sense of identity, what they think will help them survive," he says. "They got enough artillery to take care of what they need to do." He knows why Brad has no faith in the justice system. Brad was sitting beside Kelly when a not-guilty verdict was handed down on a gangster who'd shot Kelly's nephew.

But none of this excuses vengeance. "God spared your life again," Kelly told Brad in the hospital. "Why did God spare your life? Not to go and deal revenge."

Kelly needs Brad to stay resolute. He's worried about what will happen to the hood when he's too old to run Open Door and deal with the drama. "What are all these people going to do when I'm gone?" he wonders.

After Brad was released from the hospital, he went to his mother's to recuperate. Kelly visited him there. Brad's face was still flushed. He was doped up on painkillers to deal with the staples in his gut. "Gangbangin' ain't what it used to be," he told Rev.

Kelly has helped at least a dozen gangsters turn themselves in. Now he asked Brad how he was going to deal with his shooter.

"In the old days, it used to be an eye for an eye," Brad said. "I just wanna put this bullet behind me and get on.... If he gets away, he gets away."

"We all know what goes around comes around," Kelly responded.

"Well, it ain't gonna come from me," Brad said. "I just choose to let this one go. I don't work for Satan anymore. Even though he tried to kill me, everybody's got a mother."

He's confident that no matter how he deals with the shooter, his own reputation in the hood is so strong that he'll keep the respect of gangstas. "They know what I'm capable of doing, what I will do," Brad says. "This takes no stripes off me. It adds stripes, if anything."

Brad has told his closest homies not to retaliate. But while he can give the order, he can't make sure it's enforced. "There's a lot of shit going on in the hood," he explains. "There's going to be some more gunplay real soon. They knew who they shot, and there's no way all my people are going to let it ride. Once you're in the club and you get a few drinks in you and you got a pistol in your pocket, there's nothing you can tell them."

He also recognizes that his shooter may try to finish the job -- but says that's no reason to go after the shooter himself. "It's a hard decision to make, but there are consequences if I did go out and do it and get caught," he says. "Basically, I'm just thinking about my family."

This is all new for Brad. He's trying to think in a different way, struggling to redefine himself. He still wants to be known, but for positive things. He wants to be someone that his community can count on. He wants parents to trust him with their children. He wants to help kids see the light that he missed for the first three decades of his life.

When Brad went to the police station to pick up the cell phone he'd had the night of the shooting, the cops told him they knew who his assailant was. Just sign this complaint, they said, and a car will pick him up immediately.

Brad didn't sign.

On his first day back on the job at Open Door, Brad asks a colleague driving the van to pull over so that he can buy a hat. "You should do this on your own time," she tells Brad as she drops him off.

A few minutes later, Brad's back. "See, what I tell ya," he says. "In and out in three minutes." He puts a new black visor on top of the skullcap already stretched across his head.

By the time the kids who've signed up for the program start rolling in at 4 p.m., Brad's ditched the skullcap and is down to just the visor. Kelly's got a major problem with men wearing hats indoors, and he doesn't like visors any better. "What is it, a rebellion thing?" Kelly asks.

He's talking the same way he speaks to kindergartners in the program.

Brad's busy slicing sandwiches and dishing out juice. "This ain't my job," he tells Kelly.

"Well, when you go on vacation, things change," Kelly replies.

After the snacks, Brad takes charge of the third- and fourth-graders. He's big and intimidating, but the kids huddle around him, giving smiles and high-fives. One girl says that she cried when she heard he was shot. He assigns seats, knowing which kids are trouble and keeping them close. The kids are ordered to read for 25 minutes. He watches their eyes, making sure they turn the pages and that no one is faking.

It's quiet in the classroom, almost too quiet. But there's always one, and Brad orders a boy running his mouth to come sit by his side. The kid's one step away from being forced to do a set of push-ups, two from being sent to Rev's office. "Sit still," Brad tells the boy, who has the same dream of playing professional football that Brad had at his age. "Read about boats."

At the end of the session, Brad asks the kid why he didn't read.

"I did," the kid says.

"Oh, yeah, then tell me something about the book," Brad replies. "Tell me one thing, one thing, from even the first page, the first paragraph. Tell me one thing."

The kid stares at the ground and tries to keep a grin off his face.

"Yeah," Brad says. "You can't slick an oil can."

Brad makes no secret of the fact that he's after Rev's job.

"Brad has the raw ability to do it," Kelly says. "He has the street knowledge and ability to lead, in his own way." Kelly saw Brad committed to the gang. Then he saw Brad committed to his family. Now he sees Brad committed to the kids.

But Brad still has work to do, Kelly says. He needs to polish his communication skills. He needs to learn to use that charisma in a positive manner. He needs to get his diploma and maybe even some higher education, so that he knows how to run an organization. Those skills can all be acquired, though, and Brad will pick things up as he continues to mellow out from gangster life.

Rev knows. He's been there himself.

"So many are strong in one area and think that's all it's going to take, but it's not," he says. "I know how it is to keep the old man contained and suppressed. The way we used to do things in the past, that old man still lives inside of us, inside all of us."

Kelly has seen so many gangsters who think they can survive the life but end up in jail or dead because they can't live within the limits of the law. After Kelly got out of prison, he saw someone who had tried to shoot him dead before he got locked up. That old man inside him got going and wanted revenge, he remembers, but he walked away instead.

Someday soon, Brad will cross paths with the man who shot him.

Kelly prays that Brad will be able to walk away, too.