Denver NWSL

Audio By Carbonatix

Later this month, Denver local government employees will be notified whether or not they are being laid off as the city faces a $50 million budget shortfall in 2025 and an even larger deficit in 2026.

As a cloudy financial future hangs over Denver, the City Council will vote this fall to appropriate $70 million in city dollars to buy land and build surrounding infrastructure for the future stadium for the upcoming Denver National Womens Soccer League team, Summit FC.

“It’s an optics issue with the public,” says Councilmember Kevin Flynn. “I’ve had questions from a few constituents, ‘Why are you spending this if you’re in such a budget shortfall?’ I have to explain. It’s kind of complicated, but once you understand it, you go, ‘Oh, that’s right, it’s kind of pointless to not do this.'”

The proposed stadium site sits at South Broadway and Interstate 25 on the former Gates Rubber site, which has sat dormant for decades. The $70 million to help build the stadium would come from the city’s Capital Improvement Fund, which cannot be used to pay staff salaries. According to Mayor Mike Johnson, consumer spending has collapsed in Denver, resulting in near-zero revenue growth for the city’s general fund over the last three years. But the cost of running the city kept growing, causing the budget crunch currently being navigated.

To combat the issue, the city has enacted a hiring freeze through at least September, furloughed some employees and will soon begin issuing layoff notices.

Flynn, who is in his tenth year on the city council, says this time period reminds him of 2008, when he lost his job at the now-defunct Rocky Mountain News and the city had to cut staffing and other programs.

“I don’t know if this feels worse or not as bad as what happened in 2007, 2008 or 2009,” he says. “We had COVID, and we had to do furloughs back in 2021. This feels worse than that, for sure.”

But he and several other councilmembers want people to know that refusing to fund the NWSL stadium wouldn’t help these matters.

It’s All About What a Certain Fund Can be Spent On

The Capital Improvement Fund can only be used for the acquisition, repair or rehabilitation of assets that will last for at least fifteen years. Additionally, the fund can only be used for nonrecurring costs of $10,000 or more.

“It has to go toward brick and mortar or buying of land,” explains Council President Amanda Sandoval. “It’s dedicated for specific uses and has lots of specificity and guardrails around it.”

The CIF is replenished mainly by property taxes, based on property assessments each year, so the fund is growing despite the city’s sales tax revenue dipping, according to a March presentation from the Department of Finance.

Dollars from concert tickets bought at city venues like Red Rocks Amphitheatre, lottery spending, and revenue from the Winter Park Ski Resort also go into the CIF. The Department of Finance predicted that those numbers would be somewhat more conservative going forward, given the decrease in consumer spending.

But NWSL stadium funding relies on dollars already available through the CIF rather than future revenues. Before this year, the city had used money from the CIF to supplement projects that were part of the 2017 voter-approved Elevate Bonds, like the 16th Street Mall remodel and the new Denver Central Library renovation. The city has determined that interest from the bonds can be used to complete all the Elevate projects, so those CIF funds will become available for the stadium.

Of the $70 million total the city expects to spend on and around the stadium, about $20 million is needed for roads connecting the neighborhood to other parts of the city and improvements to pedestrian, bike and park infrastructure, according to the stadium proposal, while street parking, traffic lights, storm drainage, water and sewer lines, and fire and security systems are other anticipated uses of city funds.

A maximum of $50 million would be used to buy the land. Therefore, the city will have a permanent investment stake by owning the land even if the team eventually folds or moves elsewhere.

Some councilmembers also say the stadium could help boost the general fund eventually if people from outside city limits come to games and spend money in the city. Flynn sees the project as a possible way to bring new sales tax revenue to the city, as well.

“In this economic downturn, I believe that we need to invest in projects that generate economic wealth,” Sandoval says, pointing to both the stadium project and the Vibrant Denver Bond package (which, unlike the stadium package, must be approved by voters) this fall.

Community Benefit Agreement

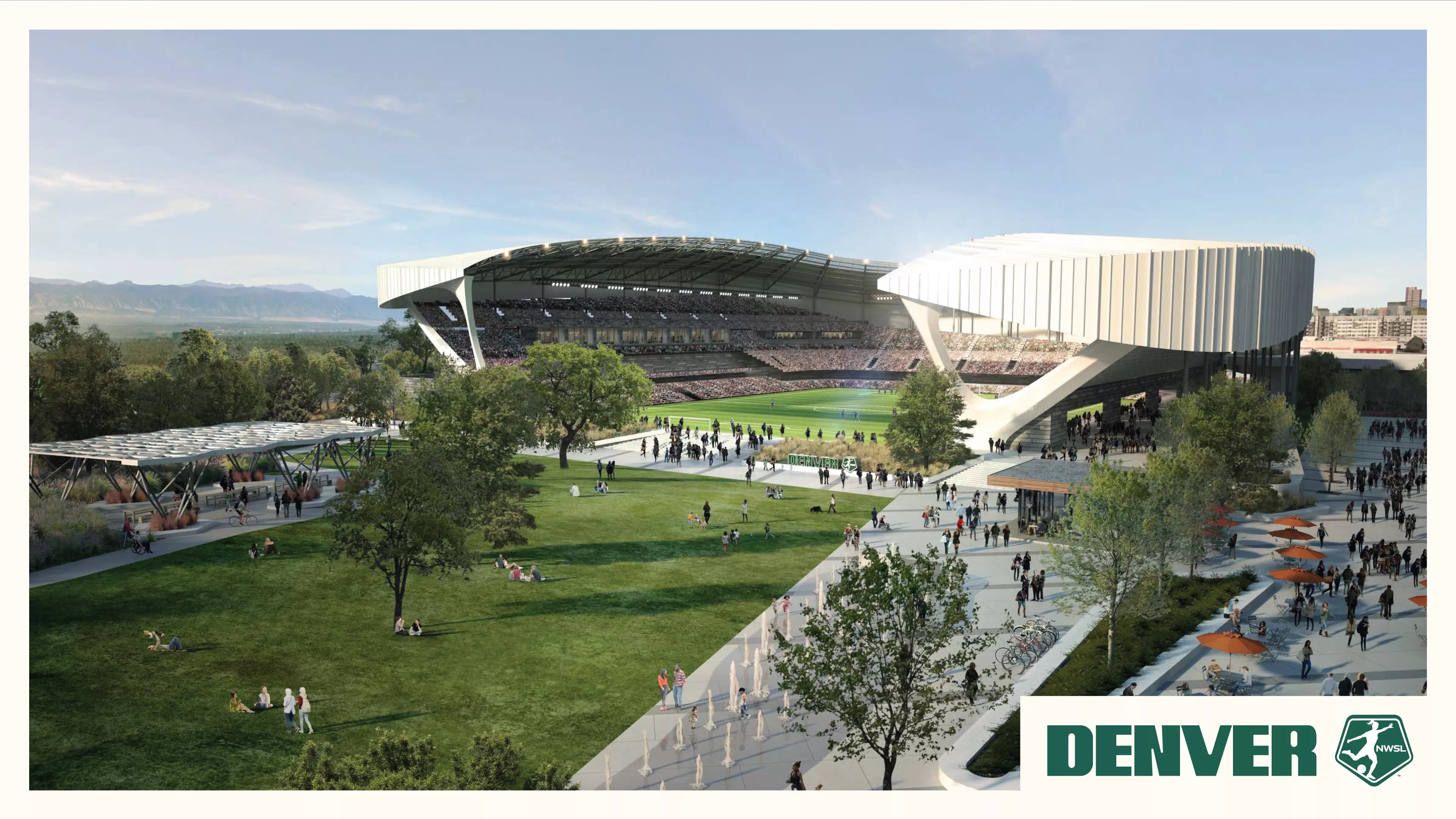

Councilwoman Flor Alvidrez, whose district is where the stadium would be, says her community desperately needs infrastructure, connectivity and open space, all of which would be improved with the $70 million from the city and the stadium project. Preliminary stadium designs contemplate a park outside the stadium, which would be open on one side toward the park to allow the public a view into the arena, another new feature the councilwoman desires.

“This is not just about the stadium,” she says. “It’s about transforming long-neglected land into a city-owned public park, safer streets, walkable connections, and meaningful public benefit. District 7 is poised to receive less than its equitable share of recent bond funding that is being pulled to things like a huge park in Park Hill so dedicating these funds to a historically underserved area is both fair and overdue.”

She also agrees with her colleagues that the construction and stadium operations will lead to jobs and economic activity in the area. Still, Alvidrez promises to be pragmatic with her final vote and will consider how the build could affect her community, mostly through a community benefit agreement negotiated with Summit FC ownership.

“My final vote and decision on any future appropriation will be made at the time of the vote, based on the full context, available data, and what best serves both the people of Denver and the residents of District 7 at that time,” Alvidrez says.

Other councilmembers agree that a community benefit agreement to ensure the team will partner with the local neighborhood around the stadium is key to their support.

“I would love to support our young women, but the city’s budget situation certainly makes this decision a difficult one,” says Councilmember Paul Kashmann. “It will be critical for the ownership group to come forward this fall with a precise and robust community benefit package to make the deal more justifiable.”

Sandoval says the CBA and rezoning are most important to her, too, and wants to make sure the city receives a return on the possible investment.

“Are there jobs?” she says. “Is there growth? Opportunity for women? Construction jobs? …How do we build generational wealth for that community?”

Earlier this year, the council approved the $70 million budget. Sandoval expects the rezoning and official move to transfer the funds will come before council as one package this fall; she hopes there will be a strong community benefit agreement presented at that time.

Though the city has no authority over a community benefit agreement, councilmembers could refuse to pass the rezoning or final appropriation if there isn’t a CBA in place.

Even with anticipated payoffs in the future on both cultural and financial levels, the stadium still isn’t an easy sell for councilmembers right now.

“They thought they found something that could help, and it really doesn’t,” Flynn says of those who have suggested using the $70 million for the stadium to fix budget problems. “It’s kind of frustrating when you can’t touch those other funds, but when you understand it you grudgingly accept it.”