Teague Bohlen

Audio By Carbonatix

Denver’s Godfather of Jazz is finally getting his due – and the spot his legacy deserves – from Colorado Music Hall of Fame.

On Tuesday, October 17, George Morrison Sr. will be inducted into the Hall in a ceremony at the city park now named for him, at 1600 Martin Luther King Boulevard. The park, with its monumental half-violin erected in honor of the jazz-era great, with signage recently updated through a community grant from Amazon, under the oversight of the Denver Park Trust and a committee of Whittier community members led by Dr. Awon Atuire. At the October 16 Denver City Council meeting, member Darrell Watson will introduce a proclamation highlighting George Morrison Sr.’s legacy and the upcoming induction; Watson will also speak at that event.

“Mr. Morrison Sr. was an extraordinary man,” says Carlos Lando, former general manager and longtime on-air host at Denver jazz station KUVO and a Colorado Music Hall of Fame boardmember who’ll also talk at the induction. “A musician. A composer. A civil rights pioneer and a Five Points entrepreneur. Because he chose to remain in Denver, he was largely underappreciated and forgotten on a national level, even though he was an international star during the Golden Age of Jazz.”

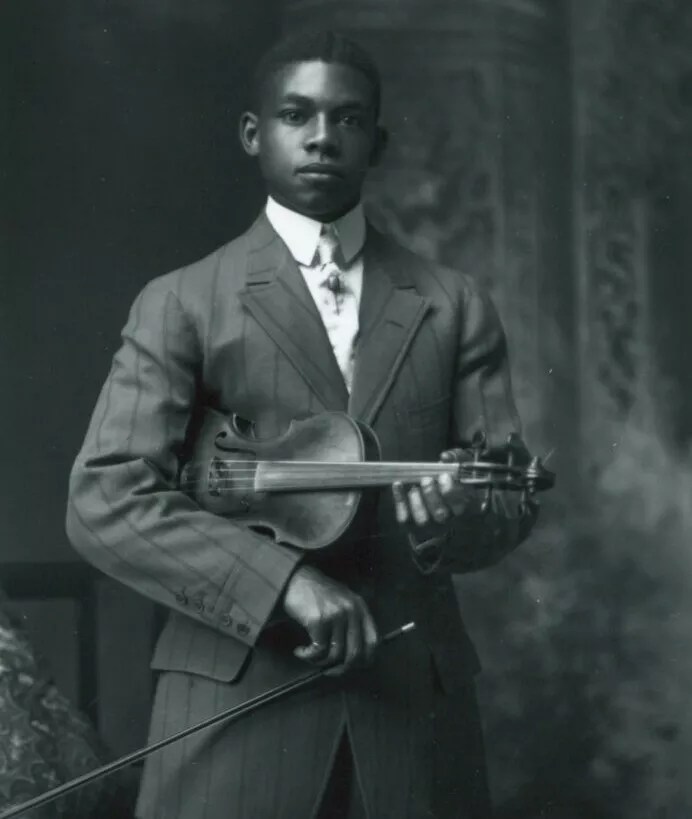

George Morrison Sr., 1891-1974.

Colorado Music Hall of Fame

That was back in the days when Five Points was known as “the Harlem of the West,” and echoed with the sounds of jazz music from not just George Morrison, a violin virtuoso and band leader, but other legends like Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, “Jelly Roll” Morton and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. “He played for kings and queens, and played with Duke and the Count,” Lando says of Morrison.

Morrison met with so much success that he set out to build a house on East 26th Street and Gilpin in the Whittier neighborhood in 1923. The community’s reaction was a racist “bombing attack,” according to Historic Denver, and a burning cross on what was meant to be a lush front yard facing Manual High School. The local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan dismantled the foundation of the home in the dark of night nearly as fast as it could be put up in the bright light of day.

But Morrison was used to persevering in the face of struggle. Born in 1891 in Fayette, Missouri, it’s said that his first violin was self-made with a corn stalk, a piece of wood and some string. In 1900, his musical family moved to Boulder, where he played for fraternities and sororities at the University of Colorado; he and his brothers would also play the mining camps in the mountains to the west and for hundreds of Jewish weddings in Denver. He moved there in 1911 when he married his wife, Willa May, but he still dreamed of playing classical violin, and eventually moved to Chicago to receive classical training from the Columbia Conservatory of Music.

Even with such credentials, no orchestras or symphonies of the day would hire black musicians. Morrison’s yearning to make music wouldn’t be denied; he formed an eleven-piece band that recorded with Columbia Records, producing a hit foxtrot called “I Know Why” in 1920 and playing regularly at the Carleton Terrace Supper Club, a tony dance hall at the corner of Broadway and 100th Street in New York City. That same year, Morrison toured Europe and played a command performance in London for King George and Queen Mary.

Morrison returned to Denver and signed with the Pantages Circuit not long after, booking performances at major cities throughout the West. A second Black ensemble, the Melody Hounds, included East High School graduate and singer Hattie McDaniel, some fifteen years before her historic Oscar-winning turn in Gone With the Wind. For many years, Morrison and Morrison’s Jazz Orchestra enjoyed a long-term residency at the Albany Hotel, which stood with grand style for nearly a century at 17th and Stout streets.

Once completed, Morrison’s house on Gilpin served as a safe haven for Black performers traveling through Denver, who were barred from most hotels because of the color of their skin. And it wasn’t only visiting big-name musicians who enjoyed the hospitality of Morrison’s home: Scores of aspiring musicians also came, taking lessons from Morrison, sometimes free of charge.

The sun shines down on George Morrison Sr.’s Whittier home.

Teague Bohlen

Morrison was instrumental in much of Denver’s musical past, including the founding of Musicians Local 623, an important union for Black performers. He also volunteered as a music teacher for Denver Public Schools – an act of charity and support for public education that doubtlessly inspired his son, George Morrison Jr., to follow in his footsteps and break barriers of his own in Denver academic history. As a nod to Morrison Sr.’s dedication to education, the Denver South High School Jazz Band will perform at the induction ceremony.

Despite all his success, Morrison never achieved his dream of playing with a professional symphony orchestra. The first African-American to play with the Colorado Symphony was Charles “Charlie” Burrell, another member of the Hall who just turned 103. Burrell played with Morrison, and recalls Sunday concerts in Golden, complete with dancing and good barbecue, where the two legendary musicians and band would perform.

“He was a real gift,” says Burrell. “A real nice guy. He treated people well. And he paid well, too. He brought jazz to Denver. Before him, there was no jazz, period. He was the first one, God bless him.”

George Morrison Sr. will be inducted into Colorado Music Hall of Fame at his namesake park, 1600 Martin Luther King Boulevard, at 5 p.m. Tuesday, October 17; admission is free. For more information, see the Denver Park Trust website.