Nick Anderson

Audio By Carbonatix

When I met Nathan Marcy way back in 1999, he creeped me the fuck out.

Back then, the Denver musician – who died Wednesday morning at the age of 43 from cancer, leaving behind his wife, the singer-songwriter Rachael Pollard, and their two daughters – had yet to make his mark on the local scene. That didn’t last long. At his rented house on 14th Avenue and Humboldt Street in Capitol Hill, he was then in the process of assembling a big group of Denver-based guitarists, myself included, to take part in a one-off performance. It wasn’t a rock band. It was an entire guitar orchestra that Nathan was going to mastermind by giving each instrumentalist a different alternate tuning that he’d devised. The idea was to let each guitarist run wild and improvise at the same time, with the result being an enormous, shimmering cacophony.

As I walked into Nathan’s house and shook his hand that first time, his intensity kind of made my skin crawl. He was quiet and shy, which I could relate to. But he also had a penetrating look that brooked no bullshit, not to mention an imposing intelligence. Making small talk with this thin, prematurely balding young man was awkward. He seemed best able to communicate by talking music. That’s when his face lit up, when his glare softened, when his laugh leaked out. I think we bonded when our conversation drifted to Robert Quine, the genius guitarist for Richard Hell and Lou Reed.

Like so many geniuses, Quine died before his time. So did Nathan. His guitar orchestra was just the beginning of his lengthy tenure as one of Denver’s most beloved and respected musicians. His is a deafening origin story. All of us – his ragtag army of guitarists – huddled in the unfinished basement of 508 East Colfax Avenue. The storefront is now La Abeja restaurant, but in 1999 it housed Chernobyl Tone Gallery, a space for experimental art and music. The members of the orchestra outnumbered our audience. That didn’t stop us from cranking our amps as loud as they could go, fingering Nathan’s strange tunings on our fret boards, and unleashing an extemporaneous wall of noise that permanently hobbled the aural capacity of everyone there. The sound of all those amps was so overwhelming, in fact, that it blew out the power at Chernobyl after a mere ten minutes. The basement fell eerily silent. The ringing in our ears was all we could hear. Nathan didn’t flinch. Without a fuss, he rushed to change the fuse, signaled everyone to continue, and resumed his humble yet thunderous baptism into Denver’s music scene.

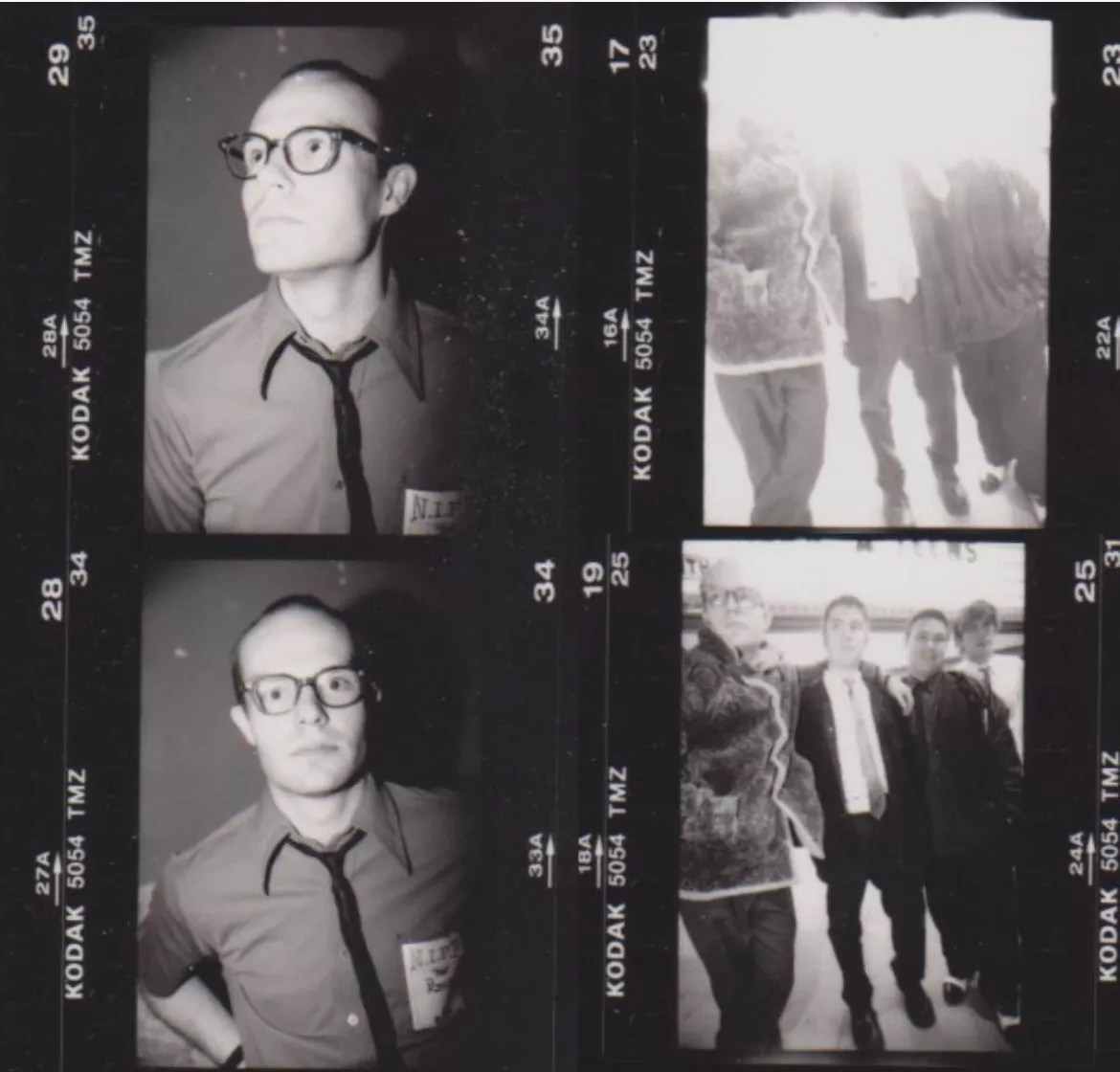

Nathan Marcy and friends.

Nick Anderson

Going forward, Nathan’s ambition was matched only by his modesty. He was equally content leaping around with a guitar in the frontline of a band as he was playing a supporting role at the back of the stage, as a drummer. And he was equally proficient at both. I’ve played or been acquainted with many Denver musicians over the years, but I’m not sure I’ve ever known one as purely musical as Nathan. His brain would have imploded without music. His lungs would have collapsed without it. Music was his language, his way of relating to people, the force that flowed through his skinny frame. And on to everyone around him.

Many great Denver bands boasted Nathan as a member since that guitar orchestra in 1999. The Risk, an explosive power-pop outfit. SpokeShaver, a brooding indie-rock ensemble. Yellow Second, an alt-rock group featuring members of Five Iron Frenzy. Riverside Drive, a folk-rock project led by Rachael, thus forming a husband-wife supergroup that they both would have been embarrassed to acknowledge. And most recently, Nathan belonged to Palehorse/Palerider, a doom-drenched shoegaze trio that, in a way, harked back to the immersive volume of his old guitar orchestra. And that’s only the tip of the list.

Nathan and I even played together once more, in a Clash cover band called the Clampdown. We did one Halloween show at the late, lamented Old Curtis Street Bar in 2006. Or was it 2007? Or 2005? Memories tend to fuck with you as the decades drift by. Anyway, I was Mick Jones, and Nathan was Topper Headon. Joaquin Liebert and Nick Anderson – Nathan’s brothers-in-rock from the Risk – were Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon. I’ll never forget how goddamn joyous it felt that night for us four friends to pay collective tribute to a band that changed so many lives, ours included.

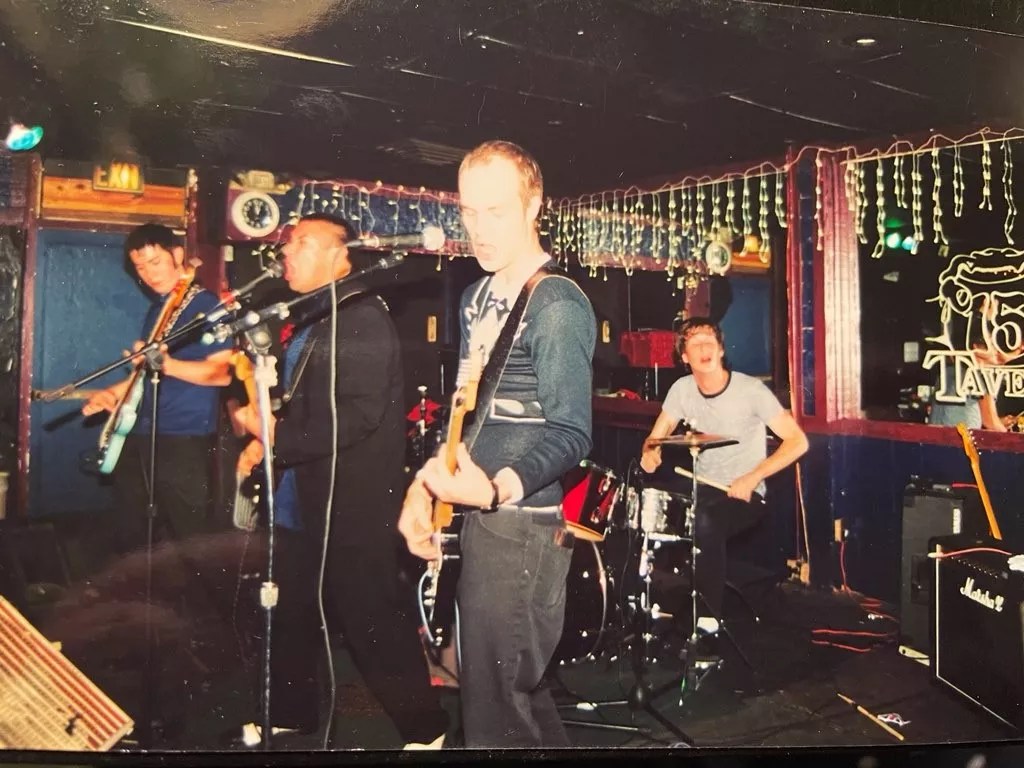

Nathan Marcy, front, with bandmates at the 15th Street Tavern.

Nick Anderson

As Nathan and I later discovered, we were both Norsemen – that is, we had both attended Northglenn High. Only we were four years apart, so we never crossed paths there. In the early ’90s, that school was not a happy place for punk weirdos like us – kids who couldn’t even fit in with most of the other punks. The last time I saw him, over the weekend, we reminisced about our high school days. I was visiting him at his and Rachael’s house near Sloan’s Lake. Friends, relatives and bandmates were flooding through their living room, trying to say goodbye without actually saying the word “goodbye.” Rachael had told everyone that if they wanted to sit with him, now was the time. Nathan remained as upbeat as he could while curled up in a ball on his couch, his voice as drawn as his body. I joked about erecting a statue of him in the courtyard of Northglenn High, with a plaque that sarcastically read “King of the Norsemen.” Without skipping a beat, his quick, dry wit kicked in. “Sure,” he said, “as long as you remove the “Nor” from “Norsemen.”

Nathan kept his long battle with cancer to himself. He didn’t stage benefit shows or crowdfund a medical relief campaign. He was a private person. And to the very end, he brimmed with grace and humility. He kept asking everyone who visited him in those final days how they were doing. He wanted to know what they’d been up to, how they’d been coping with COVID, how their kids and bands were faring. It was as if he wanted one last snapshot of his loved ones to take with him. His and Rachael’s daughters, Ava and Dottie, are as sweet, smart, determined and talented as you would expect, given their impressive pedigree. It’s hard enough to picture life without Nathan as a buddy or bandmate. I can’t imagine what it will be like to live without him as a husband and a father.

The creepiness I once felt around Nathan – back when he and I were kids in our twenties who hadn’t quite figured ourselves out, let alone each other – has long ago melted into warmth and camaraderie. His loss is a blow to his family and friends. It’s a blow to Denver. It’s a blow to music. And it’s a blow to anyone who knows what it’s like to have so much to say to the world, so much to give, and so little time.