Jacqueline Collins

Audio By Carbonatix

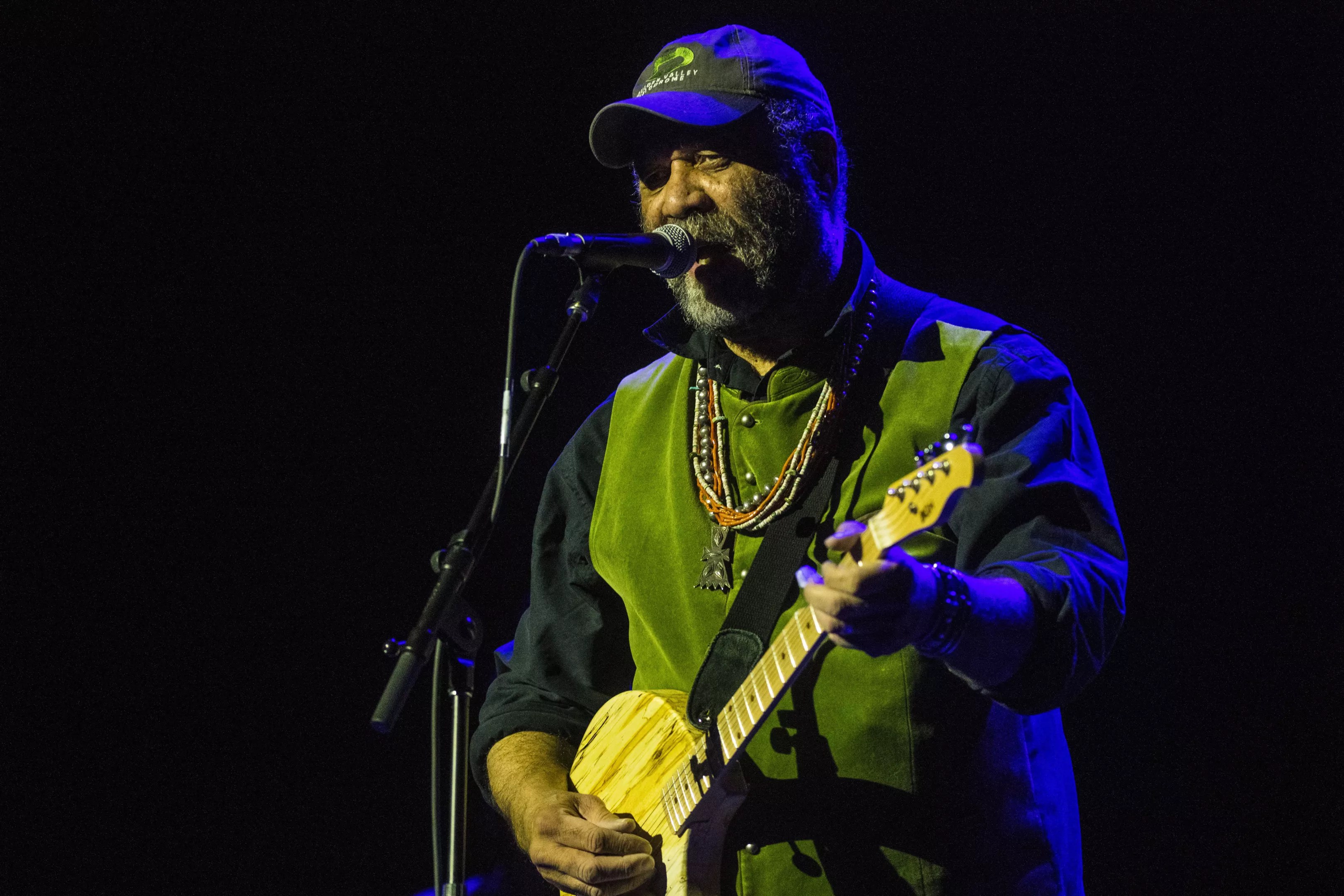

Boulder bluesman Otis Taylor hasn’t recorded a lot of covers over the past two-plus decades that he’s been making albums. With more than a hundred of his own songs spread out over fifteen LPs, he doesn’t need to.

But the banjo player, guitarist and singer has long played “Hey Joe,” written by Billy Roberts and made famous by Jimi Hendrix. Not only has it been a longtime live staple for Taylor, but he’s recorded it four times – once on his 1996 debut, Blue Eyed Monster, once on 2008’s Recapturing the Banjo, and twice on his 2015 album Hey Joe Opus/Red Meat, which PS Audio’s Octave Records in Boulder just reissued as part of a limited-edition run of high-definition Super Audio CDs.

Taylor says it was hard to convince Telarc, his label in 2015, to release Hey Joe Opus/Red Meat, which ended up being one of his most critically acclaimed albums. Taylor went to the label with the idea of making an opus of sorts, where the album would be designed to be listened to as a single piece of music in ten parts, using “Hey Joe” as its overarching theme. Taylor says people at Telarc’s European office were interested in releasing the disc, but the folks at the American branch thought the concept was too edgy.

“What else could I tell them?” Taylor says. “You can’t explain it. It was one of these records you can’t explain to somebody until you do it and they go, ‘Oh, that works.'”

For Hey Joe Opus/Red Meat, Taylor also recruited guests like Gov’t Mule’s Warren Haynes, String Cheese Incident’s Bill Nershi, singer-songwriter and guitarist Langhorne Slim, Rose Hill Drive guitarist Daniel Sproul, and jazz trumpeter and longtime collaborator Ron Miles, whom Taylor first met at a Westword Music Showcase in the mid-’90s.

The album starts with one version of “Hey Joe” using a slightly different arrangement than Hendrix’s, then moves seamlessly into one of three different versions of the Taylor song “Sunday Morning.” Taylor says he wanted the transition between songs on Hey Joe Opus/Red Meat to be almost non-existent – there are no silent gaps between the tracks – so that a listener might not even notice that a new song has started.

“If you’re not really paying attention, you might think we’re still playing ‘Hey Joe,'” Taylor says. “But we’re not. We’re playing a whole different song, because we keep the cut really close, like an opus. That’s what an opus is, isn’t it? It’s like movements put together. I think that’s what it is. Maybe I don’t know – I’m not a classical person. It sounds like an opus to me.”

Taylor ended up releasing Hey Joe Opus/Red Meat in the United States on his own Trans Blues Fest imprint, named after the festival he started in Boulder a decade ago, and in Europe on the German-based In-Akustik imprint. He says a vinyl cover of the album is displayed in the record store at the African American Museum in Washington, D.C.

“Only ten blues musicians have since made it in that little record store, like Howlin’ Wolf, Buddy Guy and B.B. King,” Taylor says. “It was a really big honor.”

Taylor guesses the museum chose to display Hey Joe Opus/Red Meat because of his quote on the sleeve: “The blues is folk music, and folk music is the music of the people.”

Taylor, now 72, was born in Chicago and moved to Denver when he was four years old. He learned about both the blues and folk music as a teenager in the ’60s at the original location of the Denver Folklore Center on East 17th Avenue, which was just a few blocks from his house. After school he would go hang out, listen to music and sometimes get free banjo lessons.

“If you didn’t have a banjo, you could just pull it off a wall and play it,” Taylor says. “Me and maybe six kids hung out there, and blues guys and people would come through town and hang out there. I’ve never seen that happen again at any place. It was a time in history, you know?”

Taylor started playing folk music as a teenager. He says he was drawn to it because of dark themes, like those in the murder ballad “Pretty Polly,” one of the few other covers he’s recorded (for 1997’s When Negroes Walked the Earth). It’s about a woman who is lured into the forest, killed, and buried in a shallow grave. “Hey Joe” tells the story of a man who buys a gun and shoots his unfaithful wife.

With his own songs, Taylor has delved into his share of heavy subject material. He likes interesting songs, and figures there’s no need for another love song when there have been so many already. On “Ten Million Slaves,” which is on the soundtrack of the 2009 film Public Enemies along with his “Nasty Letter,” Taylor tells the story of ten million slaves crossing the ocean with shackles on their legs.

“Now there are more Black folk musicians writing about issues, but they weren’t doing it ten years ago,” Taylor says. “But the people before me, if they wrote about that stuff, they’d get lynched, so they couldn’t write about that.”

Otis Taylor, who lives in Boulder, was inducted into the Colorado Music Hall of Fame in 2019.

Evan Semon

Taylor says he doesn’t like to write songs with a lot of lyrics. Once he’s got his point across, he doesn’t need to add another line. As far as lyrics go, he sees himself as something of a blues minimalist, though there are sometimes many layers to his words that delve into racism, murder and poverty.

“Once I get to the point, I don’t need to go any farther,” Taylor says. “You listen to my songs, you get the point, and that’s all you need. I’m like the anti-Dylan or something. Once you get the point in people’s head, what else do you need?

“I get the point across pretty quick, and then people can decide what they think about that song or how they feel about that issue,” he continues. “I don’t tell them what to think; I’m not a protest writer. Some people call me political, but I’m not a protest writer. I just tell the truth. I don’t try to really put people down.”

Taylor recalls first writing songs at age seven. When he was around fifteen and just learning to play the banjo, he wrote “Momma Don’t You Do It,” a song he eventually recorded for 2001’s White African. He moved to Boulder in 1967, and over the years he’s played professionally in Europe and America, including a stint with Colorado band Zephyr. He played with the late Tommy Bolin in that group; he and Bolin were both inducted into the Colorado Music Hall of Fame in 2019.

Starting in 1977, Taylor gave up playing music in public for almost two decades.

“I just didn’t get along with people,” he says. “It just didn’t seem very pure. And there was too much pain in it. I said, ‘I don’t need this.’ I had another business. I didn’t need this. I just walked away.”

For the next eighteen years, he was an antiques dealer, coach of one of the first African-American bicycle racing teams, a painter and sculptor; he also started a family after marrying Carol Ellen Bjork in 1985. They have two daughters, Jae and Cassie. The latter plays bass on many of her father’s albums and has three albums out under her own name.

“When I married my wife, she didn’t even know I played music,” Taylor says. “She was like, ‘Who are these people who call you, and you talk to them for an hour?’ That was Kenny Passarelli. He’d break up with a girlfriend and call me. I didn’t talk about music.”

Taylor says music wasn’t on his mind during the self-imposed hiatus. But when a friend, who was also the sponsor of Taylor’s bicycle racing team, opened Buchanan’s Coffee Pub on the Hill in Boulder in 1995, Taylor promised he would perform, and he recruited bassist Passarelli and guitarist Eddie Turner to play the gig.

Boulder-based Otis Taylor continues to play blues around the world.

CMHOF

“We had this sort of out-of-body experience,” Taylor says of that performance. “It was kind of cool to do the trance-blues thing.”

Trance blues is what Taylor is known for. Instead of a typical three-chord blues progression, he often writes songs that stick on one chord that repeats.

His version of the blues is just one form of trance music, he explains. Blues from Mali or the Mississippi Hill Country, the music of Ravi Shankar, some J.S. Bach compositions and even electronic music and hip-hop can also be considered trance.

“It’s the repetition that kind of hypnotizes people,” Taylor says. “They lose a sense of time when I’m playing live sometimes. It’s when you see somebody trying to hypnotize somebody – they’re doing repetition.”

While Taylor says that he sometimes writes music in a trance-like state, he doesn’t go into that hypnotic space when he performs. Shows, he says, are all about concentration. His bandmates constantly watch him, looking to see if he starts to play quietly, lightening the touch on his banjo or guitar.

“If you ever see me live, I don’t have a lot of expressions,” Taylor says. “But believe me, if I get quiet, they get quiet really quick. If you ever watch the process, it’s very intense. You can’t get very trance-like when you’re concentrating that hard. I’m up there to do business; I’m not there to entertain myself. I’m there to entertain people – I take that very seriously. I think it’s a Black cultural thing for Black musicians: It’s for them…it’s for the people.”

For more on Otis Taylor, go to otistaylor.com. To purchase the limited-edition reissue of Hey Joe Opus/Red Meat, visit psaudio.com/products/hey-joe.