Anthony Camera

Audio By Carbonatix

The radio DJ emceeing Film on the Rocks forgot to check: Is YaSi a woman or a band?

He could have figured it out before standing in front of the early birds scouting out the best seats – YaSi? What’s YaSi? – but he didn’t. So he fumbles, finally announces YaSi, and 25-year-old singer Yasman Azimi, who goes by YaSi, launches into her big night.

At first, the shivering Ghostbusters fans shuffling into Red Rocks Amphitheatre to watch the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man smash up New York City don’t pay much attention to the young woman wearing a stars-and-planets dress and fanny pack, skipping and stomping on the stage, headbanging and spitting lyrics.

Soon, they must.

With the voice of a natural-born diva, YaSi pours out hip-hop-infused R&B and lyrics so personal that they almost chafe. She holds back nothing.

Backing her on drums, Zachary Barokas, aka slackbeatz, could go hog wild, but he holds himself at bay, playing half-tempo, ensuring that the focus stays on the singer. He serves her vision, drumsticks locked to background beats he knows well; after all, he produced most of them. Some performances go by in the blink of an eye, the drummer says, but tonight, he’s forcing himself to slow down and relish the moment. This is also his first Red Rocks gig, and that only happens once.

In the meantime, Jake Barokas, Zachary’s brother, plays jazzy guitar riffs, often backing YaSi alone. Jake is the best guitarist Zachary knows, and he’s happy to fly in from Seattle for big gigs while YaSi looks for a guitarist to join her band full-time.

Alton Coward, aka DJ Five8, spins the beats, keeping the vibe light, the set moving forward and the bandmates working as one. Coward and Zachary have seen YaSi at her lowest, nursed her through hangovers, coached her through breakups and family drama, bad shows and one creative experiment after another, most destined for the graveyard. A few of the songs have had staying power, though: YaSi has kept three up on Spotify – and one, “Issues,” has been played tens of thousands of times.

Though she’s on the brink of Internet fame, YaSi avoids eye contact with the people sprinkled through seventy rows of seats, digging her gaze into the floor or directly at her bandmates. Even as she plays this milestone concert, she knows that her debut Red Rocks gig isn’t the end game. If her career’s a fifteen-hour trek up a mountain, she’s about twelve minutes in, she says. Of course, playing Red Rocks is a bucket-list experience that many artists would murder to have, but she’s already thinking about the next steps. When she returns to this venue, she hopes to be headlining.

On this cool June night, YaSi burns bright. If audience members were as clueless as the radio DJ when they came in, they’ll know her by the time her thirty-minute set is over, and know her well: She sings about partying, depression, her fears of disappointing her parents, heartache, divinity and death – all the stuff that other people would scribble in diaries and confess to therapists. “I write songs about misfortune and love,” she says.

YaSi at the 2018 Westword Music Showcase.

Danielle Lirette

Her father, Azim, listens to his daughter’s music as he rides the light rail on the way to and from his downtown office; he says he loves her songs more each time he hears them. He has brought 25 of his co-workers tonight. Forget Ghostbusters: They’re thrilled to hear their colleague’s daughter, and he’s thrilled to show her off. He admits that she didn’t fulfill the normal Persian parent’s wish for a child to become a lawyer, a doctor or an engineer. But she’s happy – and that’s what counts.

YaSi’s lyrics show that she’s a daughter who cares about her parents and what they think about her. Her mother, Maria, is a nurse, and she likes some of YaSi’s music, but not all of it. While she’s quick to say that “I couldn’t ask for a better kid,” and mean it, Maria prides herself on being blunt with her daughter – and that means she’ll criticize what isn’t working.

This trait – which Maria attributes to being Persian – once caused YaSi, at the time suffering through the tumult of puberty, to ask her mother why she couldn’t be more like American moms who tell their kids “good job.” Now, when talking to her daughter, Maria will ask, “Do you want me to be your Persian mom or your American mom?” and then dish out honest feedback or compliments as requested.

Before the show, Yasi had warned her mother not to expect an enthusiastic crowd.

That’s unusual for YaSi. She has plenty of fans; late last year 250 bought tickets to her headlining show at Larimer Lounge, which was so overcrowded that one woman, desperate to get in, claims she flashed the bouncer for admission. YaSi is positioned to headline a Bluebird-sized venue next, but she’s waiting to drop a short album before setting that up. For a headlining show, she views doing anything short of selling out as a failure. (In other words, she’s a booker’s dream.)

To YaSi, marketing matters. Image matters. Success matters. At this first Red Rocks concert, she’s just hoping to make her family and fans proud.

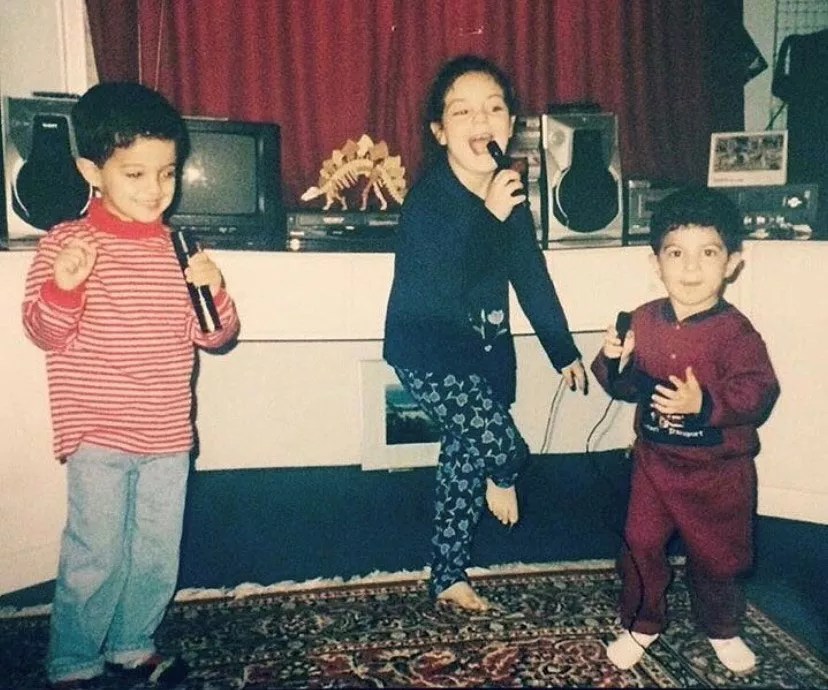

YaSi sings karaoke.

Courtesy of YaSi

For those who haven’t seen YaSi since her late teens, the whirling dervish exploding on the Red Rocks stage would be almost unrecognizable. Over the past three years as a solo artist, she has shed the insecurities that once bogged her down.

Growing up, YaSi often felt like a misfit – a first-generation American, too Iranian to fit in with her white peers at Grandview High School in Aurora and too American to fit in with her family. Her father moved to the United States before the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran. Maria lived in Iran until the ’90s, seeing the country in both its Western-influenced capitalist heyday under the Shah and as an Islamic state under the Ayatollah, when women’s rights were restricted and Western culture was banned. Growing up after the revolution, Maria had a rebellious streak. While music from the United States had been criminalized, she and her friends secretly traded bootlegged VHS tapes of American pop icons like Michael Jackson and Madonna, risking arrest to explore music from around the world. Many of her family members were killed in the Iran-Iraq War.

Azim has only returned to Iran a handful of times since immigrating to the United States. Hell-bent on having a Persian wife, on one of those trips he met and married Maria, and within weeks the two had moved to Denver together. When Maria first came to the United States, she threw herself into watching VH1 and MTV, learning to speak English from music videos and Hollywood blockbusters. After having YaSi, who was born in Denver but is a dual citizen, she continued to play music: in the car, at home, wherever she was. And YaSi was listening.

Both parents remember watching YaSi sing along to cartoons, memorizing every word after a couple of viewings. Maria doesn’t remember thinking much about her daughter’s singing, just being happy to see her child enjoying herself.

In first grade, YaSi joined the school choir and quickly stood out. Unlike the other kids – distracted, stumbling over words and singing out of tune – YaSi knew every word to every song, and her voice shone through the group. Other parents would praise YaSi’s voice to Maria, who listened with skepticism. But when YaSi was seven, her aunt, who lives in Iran, told Maria to never stop their daughter from singing. Maria and Azim took her advice.

In high school, YaSi told her parents that she wanted to make a living as a musician. “I’m not going to lie,” Maria recalls. “As a Middle Eastern person, I was like, ‘How are you going to survive as an artist?'” But ultimately, she offered her support, happy that her daughter could do something that Iranian women could not: “In my country, you cannot be a female singer.”

YaSi and family.

Courtesy of YaSi

Still, when YaSi wanted singing lessons, her mother would not pay for them until her daughter proved herself. She put her to the test, asking YaSi to imitate the great pop divas: Whitney Houston, Lauryn Hill and Christina Aguilera. When YaSi sang a stirring version of Aguilera’s “Hurt,” she brought Maria to tears and earned the lessons.

During YaSi’s sophomore year in high school, her mother bought her a Macbook Pro and a $25 USB mic, and she started making beats in her bedroom, writing songs about her feelings. She recorded YouTube videos of covers – some that drew tens of thousands of views. As she tasted fame, she wanted more.

High school proved socially difficult for YaSi. Her food smelled different from that of other students; when spring came and she prepared for the Persian New Year, her peers had no clue what she was celebrating. Some mocked her for being chubby; others teased her about her eyebrows – which today women fawn over, asking how she got them.”Genetics, sis,” she replies.

When she visited Iran, her cousins would chastise her for looking at men and dancing in the streets, fearing they’d all be arrested. Yasi walked with more of a masculine strut than many women in her Iranian family, but also with less confidence. Iranian women are survivors, she says, and strong.

After graduation, Yasi set out to lose weight. Within six months, she had lost a hundred pounds. Now that she was thin, people who once ignored her wouldn’t leave her alone – which revolted her.

With her parents’ blessing, she studied music business, first at the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley, and then at the University of Colorado Denver. She found herself frustrated because hip-hop – her first true love – was not at the center of either school’s curriculum. But she soon found mentors, including Andy “Rok” Guerrero, an original member of Flobots, at CU Denver, who taught her what it would take to succeed as a musician. And she started singing professionally, doing backup for H*Wood, a Denver-based rapper who enjoyed some success.

Back then, YaSi sang and danced with the enthusiasm of a turtle peeking from its shell: Her arms tucked into her sides, every gesture restricted, like she was pulling against the weight of a rubber exercise band. What she lacked in charisma, though, she delivered through her voice. She was flattered when H*Wood told her that he knew she wouldn’t be in his band forever – that she would be a star. She hoped he was right, but success as a solo artist seemed far away.

As she neared twenty, she recorded a five-song solo EP with H*Wood’s help, a project she ultimately scrapped. The music wasn’t up to snuff, and she didn’t want to start dropping songs she wasn’t proud of. Instead, she focused on releasing singles – some of which still exist online, but most of which she has taken down.

YaSi at the 2017 Westword Music Showcase.

Miles Chrisinger

For the past three years, despite bouts of depression and anxiety, as well as occasional professional flirtations with furniture building, fashion and graphic design, YaSi has pushed forward as a solo musician. Along with artists like Sur Ellz, Kayla Marque and Kayla Rae, she’s built a reputation for making some of Denver’s most original music, and the quality of her sound has been heartily applauded. YaSi’s been a fixture at the Underground Music Showcase and the Westword Music Showcase (after a main-stage set this year, she’ll be in the Hall of Fame) and has played Nuggets half-time shows at the Pepsi Center; her songs have been featured on local radio stations, and she’s been on the stage of most of the city’s major venues.

Along the way, she’s dipped in and out of political activism, at times telling the story of her family to show that Iranians are complex and varied in their opinions about their government, women’s rights and religion – just like Americans. At other points, she has decried police brutality and misogyny and called for an end to the United States’ wars against other nations. But sometimes she fears that speaking out could endanger family members still in Iran, and so keeps quiet.

Over the past week, she’s been especially worried for her relatives: With a United States surveillance drone being shot down by Iran and cries for a U.S. war against the country increasing, she broke her silence to speak out on Twitter – and then promptly deleted the tweet.

Her ambivalence about speaking out is shared by many pop stars, from Kanye West and Kendrick Lamar to Elton John and Taylor Swift. How much should an artist comment on social issues? How useful – both politically and to an artist’s reputation – can speaking out be?

YaSi wonders if she should wait to take strong stands until after her career booms. But that’s beginning to happen. Over the past month, she reached several milestones as an artist: After the success of “Issues” and the Red Rocks show, she joined rapper Raja Kumari for shows at the Knitting Factory in New York, Schubas in Chicago and the House of Blues in Houston. She has a new EP, Unavailable, ready to drop in the coming months, and she’s slated to play the main stage at this year’s Westword Music Showcase. To celebrate, she’s dropping the music video for “Issues.”

Despite all that, her parents worry. Her father frets that she won’t be comfortable; her mother hopes that YaSi has what it takes.

A couple of weeks after the Red Rocks show, Maria texted YaSi to say she didn’t like the Film on the Rocks performance. “It was good – but as a Persian Mom: It could be better,” Maria says.

YaSi agrees with her mom. While the young artist has accomplished a lot in a few years, she’s putting pressure on herself to do more; as an artist, she should be working harder and she should be doing better, and she doesn’t want to stop moving forward. That’s what it takes to make it – and “making it” isn’t such an impossible fantasy.

“I can quit my day job and travel the world with my friends and make music,” she says. “I can be broke and do music and be happy.”

The Westword Music Showcase runs from noon to 10 p.m. Saturday, June 29, in the Golden Triangle neighborhood; get tickets and learn more at westwordshowcase.com.