Westword and Colorado Snowsports Museum

Audio By Carbonatix

Tall, lean and weathered, a veteran of two world wars, Major General George Price Hays wasn’t a man to mince words. On February 16, 1945, he paid a surprise visit to a battalion of infantrymen from the 10th Mountain Division, eager to get down to business.

Hays had taken command of the 10th just a few weeks earlier, right before the entire outfit shipped out to Naples, late arrivals to the stalled and seemingly endless Italian campaign against some of Hitler’s most resilient and battle-tested troops. Although they had been training for years in a special camp high in the Colorado Rockies, few members of the 10th had ever seen combat.

Hays wanted them to know what was coming.

Pointing at a large map, the general gave a brief rundown of his audacious plan. In two days, he explained, the 10th would start driving the Germans out of their well-fortified positions in the Apennine Mountains, which had repelled Allied forces in three previous assaults, resulting in heavy casualties. This time around, the offensive would begin with a nighttime ascent of 1,500 feet of icy cliffs – poorly defended because the Nazis deemed them unclimbable – followed by a stealth attack on the enemy bunkers and observation posts above the cliffs, on a stretch of promontories known as Riva Ridge. That would allow other elements of the 10th to scale and seize Mount Belvedere, the gateway to a chain of peaks and hills encircling the Po Valley, crucial to the German supply lines and their path of retreat to Austria.

“You must continue to move forward, always forward,” Hays told the men. “If your buddy is wounded, don’t stop to help him. Don’t get pinned down. Never stop. Don’t give the enemy time to recover. Shoot him. Bayonet him. Brain him with your rifle. You must take his position.”

When the fighting was over, he added, those who survived would have time to rest and see the sights. He urged them to collect souvenirs from their dead or captured foes – “cameras, guns, pistols and watches” – to show their grandchildren. He closed by wishing them all good luck.

Dan Kennerly, a 22-year-old farm boy who’d played for the Georgia Bulldogs in the 1943 Rose Bowl, listened to Hays’s pep talk with mounting excitement. He had a familiar sensation of butterflies in his stomach, just as he did before a big game. The general, he wrote in his diary, “would make a hell of a football coach.”

“Don’t give the enemy time to recover. Shoot him. Bayonet him. Brain him with your rifle.”

It was a strange scene. Two-star generals don’t usually share combat plans with enlisted men or encourage them to take trophies of war. But Hays wasn’t a standard-issue general, and the 10th Mountain Division was far from a typical U.S. Army infantry unit. In its bold conception, rigorous and specialized training, the wildly diverse backgrounds of its recruits, and its game-changing approach to what would become one of the most stunning yet least heralded operations of World War II, the 10th was unique.

This week will mark the eightieth anniversary of the assault on Riva Ridge and the weeks of desperate mountain combat that followed, a deadly struggle on a forgotten front that hastened the end of the war in Europe. It’s an achievement worth remembering, particularly in Colorado. The division was forged in and around Camp Hale, sixteen miles north of Leadville, and many of its veterans returned to the state after the war and played key roles in launching several of the region’s premier ski areas, promoting winter sports, protecting wilderness areas – in short, helping to shape the Colorado of today.

A monument noting the 10th Mountain Division’s World War II campaigns and deaths sits on Tennessee Pass, above the Camp Hale site.

Alan Prendergast

Time is a more merciless winnower than war. Of the thousands of members of the 10th who saw action in Italy, only a handful of hardy centenarians survive. Yet their legacy lives on – in books, documentaries, podcasts, archives and oral histories, as well as their many contributions to the post-war outdoor recreation industry. And despite the mystique that has evolved around America’s “ski troops” and their heroics, those who were there have generally described the experience as a job that had to be done.

“Glamorous it wasn’t, particularly in combat,” declared Robert Parker, a 10th veteran who was later involved in the development of Vail, in a 1994 interview. “Elite, it wasn’t. In my platoon, we had a horse thief. We had an Indian chief. We had college kids. We had a forest ranger. And a few European ski champions. … A lot of us were the worst soldiers in the world, in terms of spit and polish and so forth. But I think our combat record speaks to the kind of people we were when it came time to do our jobs. We didn’t fit into the normal military framework, but we were good soldiers.”

Welcome to Camp Hell

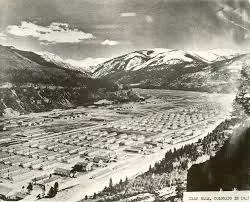

America had no mountain troops prior to the war. But the widening conflict in Europe, including Finland’s deployment of soldiers on skis to resist Soviet invaders, convinced the War Department of the need for elite combat units that could move quickly in all kinds of terrain. What would become the 10th Mountain Division began as a single battalion testing new winter equipment – including nylon climbing ropes, down sleeping bags, insulated boots and high-altitude cooking gear – on the frigid slopes of Mount Rainier in 1941, months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. By late 1942, the Army had opened Camp Hale (named for Spanish-American War hero Irving Hale) in a secluded alpine valley in Colorado flanked by thirteeners, with the express mission of training a fighting force of more than 13,000 for mountain warfare.

In its prime, Camp Hale had a thousand buildings and more than 10,000 troops.

Colorado Snowsports Museum

At the time, American skiing was largely a pursuit of those who had the time and resources to seek out lessons at upscale resorts. Reasoning that it would be easier to teach skiers how to be soldiers than to transform soldiers into expert skiers, the War Department turned to the National Ski Association and the American Alpine Club for help in locating and recruiting qualified candidates – the first time outside agencies had been trusted with such duties. The initial applicants were required to submit three letters of recommendation, testifying to their skills and character.

They were an outdoorsy bunch: young men who’d made a name for themselves on Ivy League ski teams, world-renowned climbers, Olympic athletes, European refugees with mountaineering experience, cowboys, lumberjacks, park rangers. The unusual number of college boys among the recruits set the 10th apart from the outset, as one of the most educated divisions in the entire military. The training at Camp Hale, which included grueling winter survival exercises, ensured that they were also among the fittest soldiers found anywhere.

“A lot of us were the worst soldiers in the world. But I think our combat record speaks to the kind of people we were when it came time to do our jobs.”

The recruits learned how to ski the Army way on the slopes of Cooper Hill and how to build snow caves while on lengthy maneuvers in temperatures that dipped to 30 below. (Flatlanders, like football hero Kennerly, soon figured out not to drink anything after four in the afternoon, so as not to have to get up in the night to urinate and risk frostbite of their most prized equipment.) They shouldered ninety-pound rucksacks for all-day hikes and wrote songs about it. Some of the most obsessive athletes spent their weekends skiing and hiking, too, climbing Mount of the Holy Cross or making their way over Independence Pass to Aspen and its decrepit Hotel Jerome. Others became howitzer men, communications specialists and even muleskinners; the Army figured mules would be required to haul munitions and supplies in places that trucks couldn’t go.

The long months of training together produced not only an exceptional level of camaraderie, but a casual attitude toward the rigid Army arrangements regarding rank, discipline and fraternization. Since so many of the group’s recruits, in their late teens or early twenties, were much better mountain guides than their superiors, they quickly became instructors, teaching older career officers how to ski and climb. They not only lost their awe of officers, but many went on to apply for Officer Candidate School themselves. A streak of independent thinking ran through the entire camp, generating useful innovations as well as friction and insubordination.

The 10th Mountain Division trained for mountain combat in subzero weather.

Colorado Snowsports Museum

One celebrated instance of defiance involved twenty-year-old Hugh Evans, the sergeant of a platoon dispatched on an interminable upward slog through spring snow. After five hours of misery, Evans went to the company commander to report that his men badly needed a rest. The commander demanded the names of the complainers; Evans refused. He was busted in rank and transferred to another company.

Evans eventually got his stripes back (and would earn a Silver Star under fire in Italy). But the incident reflected growing skepticism among the rank and file about their leaders’ capabilities and judgment. In 1943, one regiment of the 10th was sent to the Aleutians to help liberate the island of Kiska from the Japanese, a disastrous mission that resulted in the deaths of 24 soldiers by friendly fire in fog and sleet, and other deaths from booby traps and mines. The Japanese invaders, it turned out, had abandoned the island and slipped past a naval blockade weeks before the Americans arrived.

As the months piled up and the division swelled in size, still training, Evans worried that the war would be over before the 10th ever saw action.

“I think they are saving us for the winter or else they have no idea at all what they’re going to do with us, which is probably the closest,” he wrote in a letter home in 1944. “That’s the damned Army for you.”

That summer, as D-Day operations in France dominated the war news, orders arrived for the 10th to move from the cool heights of Camp Hale to Camp Swift, a humid inferno in Texas. (“Even our mules fainted,” Staff Sergeant Andres Vigil later recalled.) Rumors spread that the 10th was headed for Burma or some other jungle locale, and morale plummeted. By the time Hays took over as commander in late 1944, he found “some ill feeling and discontent in the Division and too many men in the guard house,” a situation he blamed largely on the group’s impatience to join the fighting.

But the wait was almost over. A week after Thanksgiving, members of the division’s 86th Regiment boarded a train from Camp Swift to Virginia. A few days before Christmas, the 85th and 87th regiments followed. From there they all traveled by boat to Naples, a battered port littered with scuttled and sunken ships.

They were headed for the front.

Seizing the High Ground

A statue of a 10th Mountain soldier graces a town square in Vail.

Alan Prendergast

Always in search of ways to boost the image of the American soldier, the Army’s publicity machine went into overdrive gushing about the “ski troops” long before the 10th had done anything worthwhile. Their striking white camo outfits graced the covers of national magazines. Newsreels depicted them showing off their moves in fresh powder or on improvised jumps.

The real story was far less cinematic. Aside from several daring reconnaissance patrols, most of the division’s accomplished skiers never did any skiing at the front. Because of shipping snafus, most of their fancy winter gear never even arrived in Italy.

But no one could take away their training, the months of preparation for combat in swampy heat and bone-jarring cold. As it turned out, climbing would prove to be a more useful skill in the Apennines in spring than skiing. That, and being good at digging in, repelling counterattacks and moving forward, always forward.

The top brass were keen on taking Mount Belvedere, the most prominent of a series of peaks overlooking a key highway and the Po Valley; as long as the Germans held the high ground, the effort to liberate northern Italy was stalemated. But General Hays recognized that a direct assault on Belvedere would be a bloodbath. The first task, he decided, was to eliminate the enemy’s observation posts on nearby Riva Ridge, from which they could call in artillery strikes with great accuracy. Hays sent the 10th’s best climbers to find a route to the top of the supposedly unassailable ridge; they found five.

On the evening of February 18, 1945, 700 men from the 86th Regiment made an improbable night ascent of Riva Ridge, using four of the five narrow, slippery routes and maintaining strict silence. They arrived at the top shortly before dawn, routed the enemy and incurred no deaths, only one wounded – a spectacular operation that would be studied by students of military history for generations to come.

The attacks on Belvedere and neighboring peaks were more costly. Although German air power was all but nonexistent, the 10th faced an uphill gauntlet of mines, machine-gun nests and a wide array of artillery. Even when they had successfully driven the enemy back, a ferocious counterattack would commence within hours. General Hays, who had fought in the Battle of the Marne as a young cavalry officer and witnessed the battles of Cassino and Anzio and the Normandy landing, would describe the 10th’s firefights as being “as strongly contested and as bitter, and in many instances more intense than any I had experienced.”

Intense – and harrowing. Marlin Wineberg, who’d joined the 10th at age nineteen, was the only member of his platoon to survive several days of fierce shelling on the denuded slopes of Mount della Spe. He emerged from the ordeal clothed in rags and armed with scavenged ammo, his hearing almost gone. “It was almost every man for himself,” he would later recall.

“What I’m smelling is blood.”

After watching the life ebb out of his platoon sergeant, shot in the chest, a seething Hugh Evans led an impromptu charge on machine gun nests on Mount Gorgolesco, tossing grenades and firing his machine pistol as he went. He captured one position, then another, then twenty Germans, who surrendered while Evans covered them with an empty gun.

Bob Parker rejected a foxhole he’d dug, considering it too exposed – only to have two close friends occupy it and die five minutes into the evening’s howitzer barrage. The sight plunged Parker into shock; he could recall nothing of subsequent events until he abruptly snapped out of it five days later, surrounded by members of his unit.

Dan Kennerly witnessed scenes of carnage that were beyond anything he could imagine and that he could never forget. In his diary entries, he did his damnedest to call it as he saw it: “The evidence is clear as to what happened to C Company. Their bodies are scattered along the slope. They are lying everywhere, frozen in many different positions. Some have their arms or legs sticking straight up. Others remain in firing position. They all have a pale yellow waxy color, like artificial fruit.

“There’s a strong scent. At first I cannot place it. Now it comes to me. It’s the odor of a slaughterhouse. What I’m smelling is blood.”

Although it was one of the last infantry units to enter the war and engaged in combat for less than three months, the 10th sustained one of the highest casualty rates of any Allied division in Europe, reporting close to a thousand deaths (and another 4,000 wounded) out of a force of 13,365. In some companies, the casualty count was more than 50 percent.

Little remains of Camp Hale, designated a national monument in 2022, but old signs (and old ammo).

Alan Prendergast

Horrific as it was, the loss of lives would have been much higher if not for the 10th’s nimbleness and improvisations. Working from plans first developed at Camp Hale, engineers constructed a mountain tramway overnight that allowed for speedy evacuation of wounded men, who might otherwise have died hours from help. Troops commandeered civilian and enemy vehicles, farm machinery, small boats and other gear to keep moving. With help from Italian partisans, entire battalions outraced their air support, artillery and supply lines, showing up where the Germans least expected them and defying the usual edicts about not leaving their flanks or rear exposed to counterattacks.

As they broke through the mountain strongholds and raced across the Po Valley, the front-line companies captured so many prisoners along the way that they could no longer spare the personnel to guard them; many were disarmed and sent to find other units that could accept their surrender. (Not all surrenders were accepted. Several accounts from 10th veterans indicate that German snipers who shot at unarmed medics, as well as SS officers or others who waved a white flag and then opened fire on approaching Americans, may not have made it to the safety of POW camps.)

The division’s relentless pursuit of Hays’s “always forward” mantra resulted in achieving all its objectives in far less time, with far fewer casualties, than anyone in the Allied command had anticipated. The division was in the vanguard of the Fifth Army’s advance and was the first to cross the Po River. The final battles of the spring offensive brought the 10th to the northern shore of Lake Garda, not far from the Austrian-Italian border. On April 30, 1945, just two days after Mussolini’s body was put on display by partisans in Milan, troops from the 10th occupied the dictator’s grand villa on Lake Garda. On May 2, the German army in Italy surrendered.

The mountain troops celebrated with cognac and champagne liberated from German warehouses. Bob Parker threw his helmet away. Dan Kennerly stripped out of his mud-caked uniform and took a dip in the icy lake. An officer told him to get a shave.

“The story of the 10th is similar to that of a lighted match,” Kennerly later wrote. “It glowed brightly, did its job, then faded into obscurity.”

Camp Hale today. Buildings were scrapped and sold to local ranchers or shipped to other Army bases.

Alan Prendergast

The Legacy

The 10th was formally deactivated on November 30, 1945. It would eventually be revived as a “light infantry” division and become the most deployed Army unit of the past two decades.

Camp Hale was deemed expendable. Even before the war was over, German POWs were put to work demolishing the place. Some of its materials were shipped off to Camp Carson or sold to local ranchers. In the 1960s the CIA set up a covert training camp for Tibetan guerrillas in what was left of Hale, but little of the camp survives today beyond the pillars of the old field house. In 2022 President Biden designated the site as part of the 53,804-acre Camp Hale-Continental Divide National Monument.

Many of the 10th’s original members went on to start their own businesses. Not surprisingly, a disproportionate number of those businesses involved high-altitude pursuits of one kind or another. Some of them transformed Aspen from a moribund mining town to a world-class ski resort; others launched or expanded dozens of ski areas from California to Vermont or were significant contributors to other aspects of the emerging outdoor recreation boom.

“The big business men in Denver told Pete we didn’t really need another ski area. So he went ahead and built Vail.”

Bill Bowerman (major, 86th Regiment) became a trainer of Olympic track stars and co-founded Nike. David Brower (lieutenant, 87th) turned the Sierra Club into the country’s foremost environmental advocacy group. Others played significant roles in improving ski, camping and climbing gear or in establishing groups such as the National Outdoor Leadership School and the National Ski Patrol.

Soldiers from the 10th had their hands in many innovations, from Gerry backpacks and Outward Bound to introducing nylon rope to recreational climbers. “The ski industry is the most visible and talked about part of their legacy,” notes Dave Little, the historian for the 10th Mountain Division Foundation. “But if you look at the growth of the outdoor industry as a whole, it’s important. All this surplus military gear and these people trained to live outdoors and be comfortable, it really exploded that industry.”

From childhood, avid skier Pete Seibert (sergeant, 86th) had dreamed of building the world’s most beautiful ski resort. Badly wounded by a mortar explosion during the 10th’s Italian campaign, Seibert wasn’t expected to survive the war, much less ski again. But after many months of hospitals and rehab, he joined Aspen’s ski patrol and the U.S. Ski Team. In 1957 a uranium prospector showed him an enormous sheep meadow graced with pristine slopes and bowls of deep powder, not far from where Seibert had trained at Camp Hale. Seibert sought out Bob Parker, now editing a ski magazine, and told him he’d found his dream resort. Parker soon came on board for the birth of Vail, and is credited with coining the phrase “Ski Country USA.”

“All the big businessmen in Denver told Pete that we didn’t really need another ski area because we already had Aspen,” Parker later recalled. “So he went ahead and built Vail. They told Bill Bowerman that there were plenty of sneakers in the world, we didn’t need new track shoes and gym shoes. And he went ahead and built Nike. … It never occurred to me that we couldn’t get it done. That’s been a real legacy of the 10th.”

Another legacy of the 10th stems from its unusual degree of esprit de corps. Veterans began holding annual reunions and arranging group excursions back to the battlefields of Italy long before such gatherings became commonplace, and the extensive networking led to the creation of a national association that thrives to this day. That, in turn, led to the establishment of the 10th Mountain Division Resource Center, a vast repository of materials related to the group’s World War II adventures. Jointly administered by the Denver Public Library and History Colorado, the collection includes military records and manuals, training films, thousands of letters home, hundreds of hours of oral histories, dozens of unpublished memoirs and diaries, photographs, scrapbooks, and other artifacts donated by vets and their families.

“We were just guys who liked the mountains.”

Hundreds of photos and artifacts from the collection were on display as part of History Colorado’s extensive exhibit on the 10th, which closed a few weeks ago after a very successful eleven-month run. Sydney Mauck, HC’s Anschutz military collections specialist, says the exhibit drew many “comments of gratitude” from visitors who were amazed at the scope of the division’s exploits and its post-war contributions.

“A lot of people left with a greater appreciation for the legacy,” Mauck says. “For the descendants, it was very impactful to have their uncles’ and grandfathers’ stories shared.”

So many stories are in those archives. The story of Ralph W. Hulbert, for example, one of two soldiers in the 10th “authorized to use a bow and arrow as their secondary weapon.” The story of a 10th reconnaissance group helping themselves to Italian horses and embarking on what may have been the last cavalry charge ever by the U.S. Army. The story of Percy Rideout, who survived Riva Ridge and a sniper bullet to the cheek, ended the war with a ski trip to Austria, then returned to Aspen with a few other Camp Hale grads to build up the ski school and the resort.

And thousands more.

“We were just guys who liked the mountains, liked to ski, and had been active all our lives,” Rideout said in a 2005 interview. “We just felt that was what life was all about.”

The National Ski Patrol and 10th Mountain Division will commemorate the eightieth anniversary of the battle of Riva Ridge with a torchlight parade in Vail on February 22. Learn more here.