Denver Public Library Archives

Audio By Carbonatix

Denver looked like a different city fifty years ago, especially while riding through it.

In 1975, the Mile High City still didn’t have the “cash register” building at 1700 Lincoln Street, the most recognizable part of the Denver skyline. There was no Empower Field, Ball Arena or Coors Field, and Westword was still two years away from publishing its first issue.

And bike lines were few and far between.

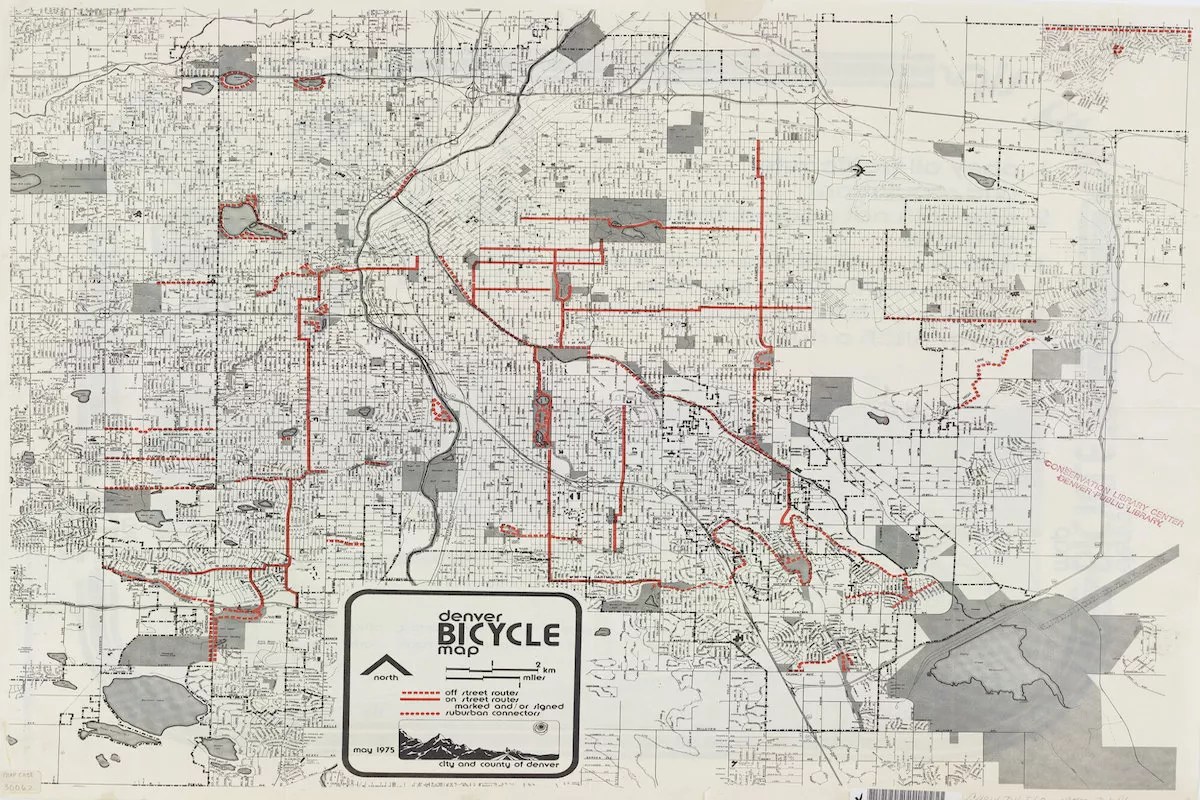

A 1975 map of Denver’s bicycle routes published by the city suggests that Denver cyclists have been dealing with the same challenges for a long time, but it was a much more limited experience back then.

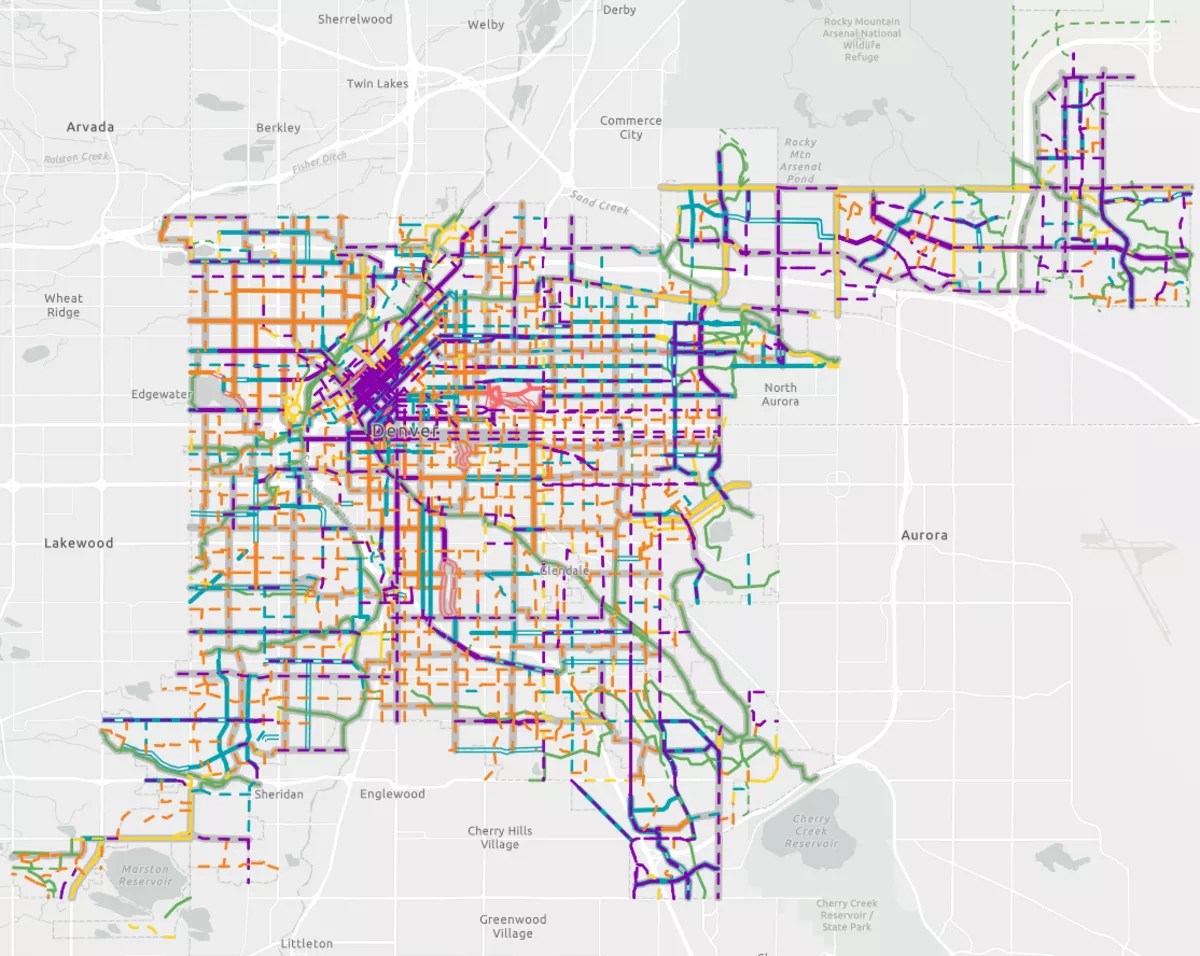

In June, the city released its newest bike map, which includes plans for improving its bikeways over the next twenty years. Love or hate the newer bike trails and lanes designed by the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure (DOTI), they show a lot of progress compared to the 1975 map. From significant expansions to the Cherry Creek Trail to laying more paths in historically disadvantaged neighborhoods, here are some of the changes and continued problems we found.

Almost Zero Street Routes in the Highlands

Most cyclists enjoy riding on paved trails, where they don’t have to risk their lives sharing lanes with cars. But if you had to bike in the Denver streets today, you’d probably want to do that in the northwest neighborhoods, like the Highlands, Sloan’s Lake and Berkeley.

Today, thoroughfares in that area like West 35th Avenue and North Perry Street are considered “neighborhood bikeways,” a city term referring to streets fitted with traffic slowing measures like electronic signage, lower speeds limits and speed bumps. In the next twenty years, that area is expected to get more bike lanes, likely with short dividers called zippers

That all fits with the character of the area today, which is known as a home for young families and forward-thinking, eco-friendly Millennial yuppies. But back in 1975, the only bike lanes out there were unpaved trails that circled Berkeley, Rocky Mountain and Sloan lakes.

The historic character of the neighborhood was still changing, and it was a couple decades removed from having streetcars, which were replaced with buses in 1950’s, according to History Colorado. Overtime, that evolution would bring in one of Denver’s best connected network of bike routes; today, the Highlands still has biking infrastructure that city officials want to replicate across Denver.

Denver bicycle map from 1975

Denver Public Library Archives

Routes to Nowhere Aren’t New

One of the biggest complaints by Denver cyclists today is that they’ll ride in a bike lane for miles before it suddenly comes to an end with no connection to another trail. That complaint has influenced the city as it upgrades bike routes, with a priority over the next twenty years to create a more seamless network that allows cyclists to get to any part of the city without leaving a bike lane or paved trail, according to DOTI.

The 1975 map reveals that this problem is hardly bew. If you decided to take a bike ride down Steele Street in 1975, you’d only be on a designated bike path from east Exposition to Yale avenues. That’s less than a four-mile ride, and you’d have either turn back the same way you came or take a chance trailblazing your own route by sharing streets or sidewalks.

Similar floating bike routes to nowhere sat just outside of Denver’s city limits but are included on the 1975 map. Several trails extended west from Sheridan Boulevard for barely two miles on streets like west Mississippi, Florida and Jewell avenues. Another segment on West 10th Avenue extends west for only a mile and half from Sheridan Boulevard to the Lakewood Country Club.

Hints of Discrimination

West, northwest and north Denver neighborhoods were home to most of the city’s Hispanic population and hubs of Chicano activism in the 1970’s. La Alma was the scene of the West High School blowouts in 1969. The Crusade for Justice opened Servicios de La Raza in Sunnyside in 1972 to offer Chicanos on the Northside access to basic social services.

As Chicano activists back then were looking at Denver’s 1975 bike map, they probably noticed that all the historically white neighborhoods around the University of Denver and Cherry Creek had many more miles of bike routes than west and northwest Denver.

Five Points, a historically Black neighborhood north of downtown, only has a small section of a bike route along Sixteenth Avenue, from Downing Street to Broadway.

The few bike routes that did exist in west Denver are marked as “off-street” bike routes, likely meaning they were unpaved. Some west Denver roads, like Irving Street and West 13th Avenue, did have “on-street” routes, but they didn’t connect to longer routes like those in central Denver.

That’s changed, fortunately, but so has the character of Denver’s historically Black and Chicano neighborhoods, where gentrification has unfolded over the last few decades.

Denver’s most recent bike map, released in June. Dotted lines show improvements the City of Denver hopes to make over the next twenty years.

Courtesy of DOTI

Looking for the Cherry Creek, High Line Canal and South Platte Trails

Some of Denver’s most iconic bike trails would be hard to notice on the 1975 map, but the historic High Line Canal is easy to spot. The 140-year-old ditch was converted into the popular trail by Denver Water in the 1960’s. The 1975 map traces the bends where it meanders in and out of Denver near its borders with Arapahoe County.

Plenty of today’s cyclists are bigger fans of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek trails, as neither are interrupted by street crossings like High Line. However, the city had just started working on the South Platte Greenway Trail project in the early 1970s, and finished installing the trail in 1975, so it was too late to get on the bike map.

On today’s bike map, the South Platte River trail is a long green line that runs 35 miles for the entire length of Denver, with westward extensions sprouting out along gulches. It’s rivaled only by the Cherry Creek Trail, which is 45 miles when including sections in Aurora.

The only trace of the Cherry Creek Trail on the 1975 map is an “off-street” route along the Cherry Creek that starts at Cook Park and runs about seven miles to West Colfax Avenue and Speer Boulevard. Denver started planning the Cherry Creek Trail in 1972, but its first section didn’t open until 1988, according to Colorado Community Media.