Jay Vollmar

Audio By Carbonatix

Fifty years ago, Al Rollinger was a young landscape designer who’d recently graduated from Colorado State University and was “grousing about the lack of variety of trees growing here as opposed to anywhere else,” he recalls.

“How do you know?” a legendary nursery owner asked him. “Have you ever looked?”

So Rollinger looked. He started out with a visit to the Denver Forestry Office, where the city forester kept track of local trees on 3×5 recipe cards. After studying those, he began walking around the parks, then finally got in his car and drove the streets of Denver, looking for trees that were “a little more exotic” than the common American elm, silver maple, linden and ash. Some were so exotic that Rollinger would “wander in with an armload of brush” to the office of James Feucht with Colorado State University Extension. “I needed an expert above me,” he recalls.

As he found each exotic tree, Rollinger would document its location, diameter and height. After two years, he had a list of over 1,100 interesting trees in Denver comprising 46 species. In 1969, Feucht had his secretary type up Rollinger’s “Tree Pioneers of Denver,” and then Rollinger went about the business of building a landscape-design career. “I never thought the report was going to go anywhere,” he says.

But it did. The legendary Panayoti Kelaidis, director of outreach for the Denver Botanic Gardens, found Rollinger’s report in the DBG library. And now, five decades later, the Rollinger Tree Collection 50-Year Survey Project is almost complete. A collaboration of the DBG, the Denver Forestry Office, CSU Extension, Colorado State Forest Service at CSU, the Colorado Tree Coalition and other local groups, and supervised by DBG outreach project coordinator Ann Frazier, the project has used master gardeners, tree enthusiasts and other volunteers to update the original Rollinger report, looking for the trees he’d documented fifty years ago, then measuring the ones they found.

Of the 1,148 trees on Rollinger’s original survey, 691, or 60 percent, are still alive. The survival rate by species ranges from under 30 percent to over 80 percent, with the Kentucky coffee tree and bur oak proving the heartiest; fewer than a third of the Norway maple and European larch made it through the past five decades. And while beech trees remain Rollinger’s favorite, the oaks “just thrived,” he says. “It should be the first tree recommended for this area.”

But the second survey also revealed that many of this city’s valuable old trees are at risk as Denver grows and changes, endangered both by natural causes and unnatural development. “Here we are in the most unlikely place for trees to thrive,” says Rollinger. “They’re just darn hardworking things, trying to get by.”

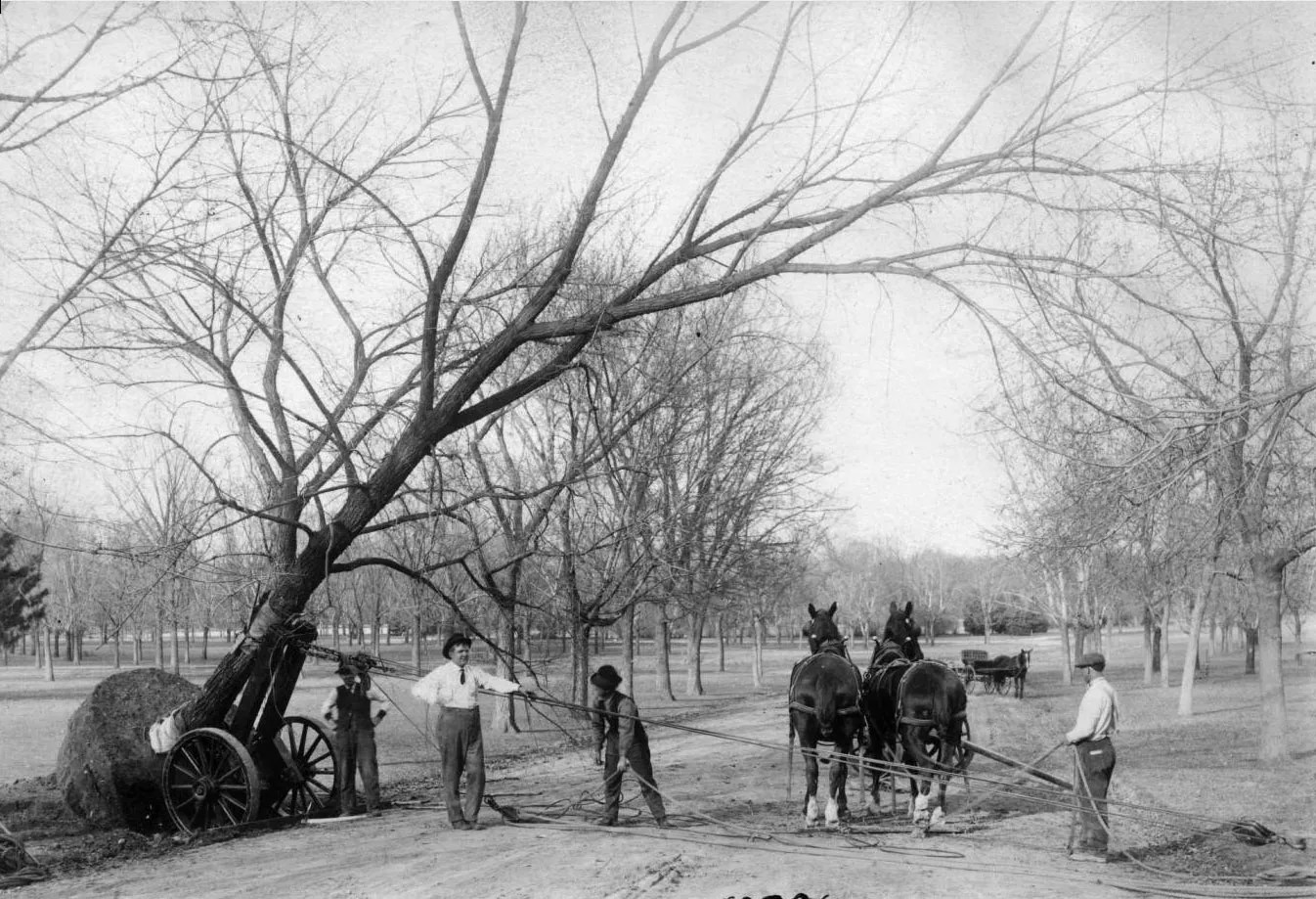

The City Beautiful Movement included planting trees in City Park.

Denver Public Library

That there are trees at all on the Great Plains speaks to the dedication of this city’s arborists, both official and amateur. “Denver is different from typical East Coast cities, which cleared the forests to build,” notes Sara Davis, urban forestry program manager in the Denver Forestry Office, part of the Department of Parks and Recreation. “We built the city, then put the forest back.” Very few of the trees in Denver are native to the area beyond the cottonwoods and willows that grow along riparian corridors that cut through the shortgrass prairie. The rest are transplants, like so many Denver residents.

Since this city was founded in 1858, there have been several big planting pushes. Robert Speer, Denver’s “City Beautiful” Mayor, made the urban landscape a major focal point of his administration. In 2005, Mayor John Hickenlooper introduced the Mile High Million Tree Initiative, which called for planting an additional million trees around the nine-county metro region by 2025; that effort currently stands at about half a million trees, Davis says. Under current mayor Michael Hancock, the focus has moved to “stewarding the 2.2 million trees we have in Denver,” she notes.

But the city isn’t stopping there: Earlier this month, Denver City Council adopted the Game Plan for a Healthy City, a twenty-year Parks and Recreation proposal that calls for adding parkland, facilities, recreation programs…and trees.

In the meantime, the city’s forestry division oversees “every tree on every parcel in the city, to make sure that they’re safe to be around,” Davis says. With late spring storms, that involved supervising cleanup not just of the 185,000 trees on public right-of-ways (including those strips of land between the sidewalk and the streets that are known as “tree lawns,” which homeowners must care for), but the 75,000 trees in Denver parks, which hold some of the city’s biggest and oldest. Champions, in fact.

Golden raintrees made Al Rollinger’s report.

Denver Botanic Gardens

A State Champion Tree is the largest-known specimen of a tree in a state, according to a scoring system devised by American Forests. The nonprofit Colorado Tree Coalition tracks this state’s champions, as well as “notable” trees, or runners-up. Forty of these champs are at the Denver Botanic Gardens, while fourteen more champions and 29 “notable” trees are located in Denver parks or along the city’s parkway system. A few of these even made the Rollinger survey.

To update that survey, Frazier hosted events around the city, bringing together volunteers (including Rollinger) and giving them a list and a general map of the trees surveyed in the area fifty years before. Since Rollinger hadn’t measured any trees under a foot in diameter, “any tree we were looking for was pretty big,” she says. But that didn’t mean they were easy to find: GPS was still decades in the future when Rollinger tracked down his trees. When teams did locate one now, they’d measure the diameter, take a photograph, and definitely note the GPS coordinates for future surveys.

“A lot were on private property,” Frazier says. “We’d leave a letter on people’s doors, asking permission to go into the yards.” They didn’t hear back from everybody, so the teams had to estimate the size of some Rollinger survey trees. But they found plenty of additional information about other trees, which will be shared when the fiftieth-anniversary report comes out this summer.

“Through the process, we learned a lot about the history of trees in Denver,” Frazier says.

“Living history,” concludes Rollinger. “You’re watching your life pass in front of you, then see a tree and, my God, he’s still here!”