Tim Gabor

Audio By Carbonatix

The woman was to show up at the U.S. Customs and Border Protection office at 9 a.m. to view the document, and department officials weren’t entirely sure what was going to happen from there. Two lawyers with the U.S. Attorney’s Office would be present. An archivist specializing in historical artifacts had been brought in. Armed guards – four of them – would watch over the meeting to make sure that everything went over smoothly. No funny business. No sudden moves. Everyone figured this document viewing on May 25 near Denver International Airport would be an emotional one for the woman. She’d already been sitting in her car in the parking lot outside, crying, since midnight, steeling herself for what was about to occur.

In fact, Julia Turing had been rehearsing this moment for weeks, anticipating it for years.

In early 2018, federal agents had seized a number of historical artifacts from Julia’s Conifer home that had originally belonged to British code breaker and computer science pioneer Alan Turing, the subject of The Imitation Game, a biopic starring Benedict Cumberbatch released in 2014. That’s when most people learned about Turing. They learned about Julia in 2020, when the U.S. Attorney’s Office filed a complaint that accused her of stealing Turing’s belongings from a British boarding school during the 1980s. News outlets around the world ranging from the Associated Press to the BBC ran stories quoting the government’s court filings about this strange Colorado woman who had devoted much of her life to an early-twentieth-century math genius, had purportedly taken some of his posthumous relics without permission, and had even changed her last name to match his in some kind of homage. What was behind Julia Turing’s obsession? Derangement? A kind of fetish? Or something else?

In all the coverage, one thing was missing: Julia’s own voice. Not until Westword reached the 59-year-old via a P.O. box listed on some court documents did any media outlet obtain her side of the story.

As Julia prefaces it, “Alan Turing saved my life.”

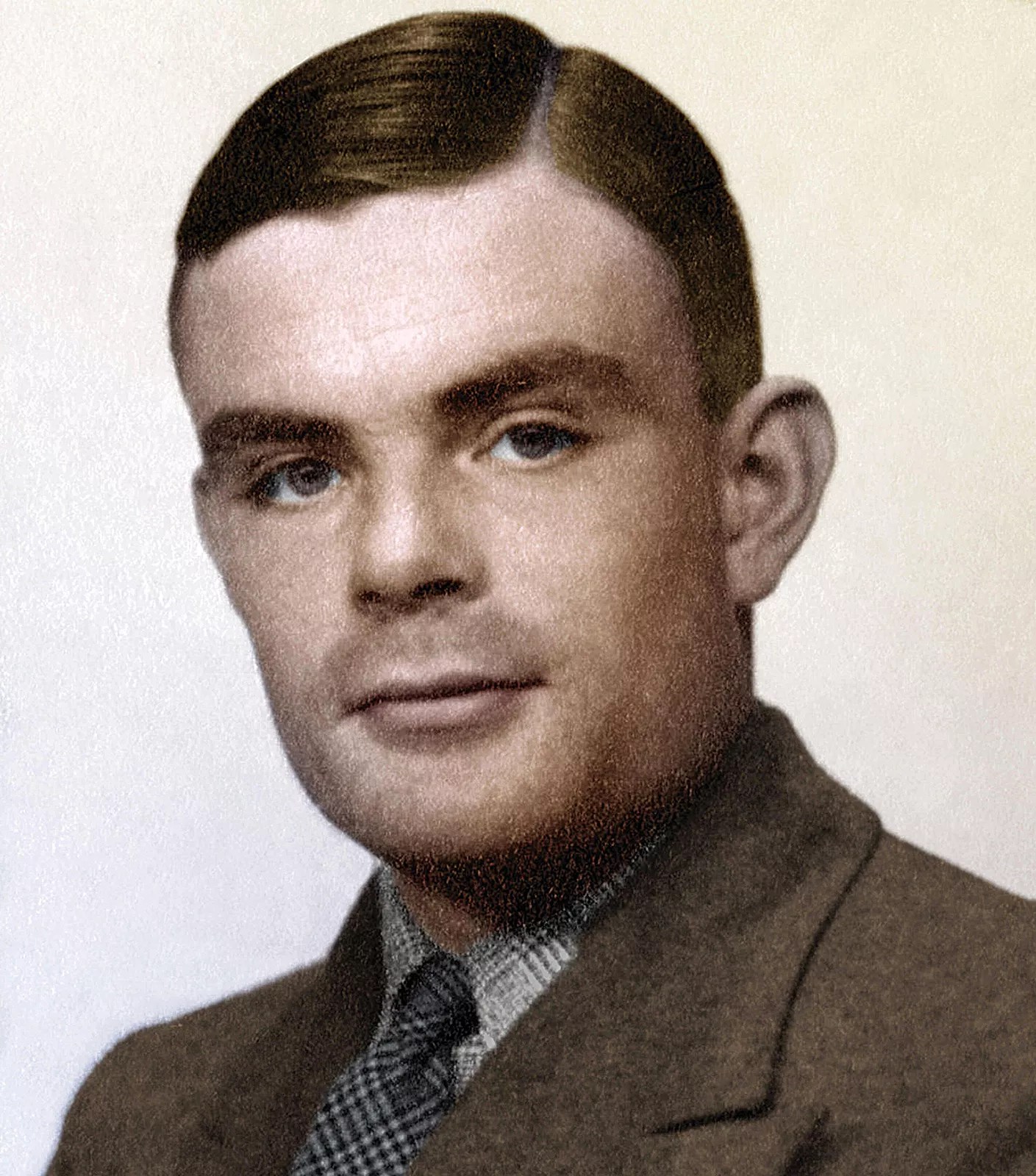

Alan Turing is considered a founding father of theoretical computer science.

Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo

In the late 1960s, the little brown-haired girl was finally enjoying a period of relative peace when her mother returned to pluck her off the front porch of her first foster home. Known then as Julie Ann Schwinghamer, the child had been cared for by a Native American family near Squaw Valley, California, after both of Julia’s parents had abandoned her. Her father had left the family when Julia was three. Her mother had taken to the bottle, then Valium, all the while prone to violent outbursts.

In contrast, living with a foster family and running barefoot around the countryside was like a dream…until Julia’s mother came calling. Julia now says her mother had discovered that she could claim additional welfare with little Julia under her roof. And so her chaotic family life picked up where it had left off, this time in the regional farming hub of Dinuba, California. Fights and screaming matches, including with Julia’s brother, were almost daily occurrences. Amid the chaos, Julia didn’t learn to read or write, and the local elementary school held her back in second grade. She tried running away multiple times. Still, Julia had her momentary escapes, including the movies. And so on one hot summer afternoon, when Julia’s mom wanted her out of the house, she went to the cinema on Dinuba’s main street to see what was playing. The film was Stanley Kubrick’s sci-fi classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

“I was really drawn into it,” Julia recalls. “And what disturbed me most was HAL 9000.”

She’d never seen nor imagined anything like the talking computer in Kubrick’s film, which infamously turns on its human masters once they’ve left Earth’s orbit. The image of HAL’s unblinking red eye wore on her until Julia did something she’d never done before: She went to the public library.

Timidly, the girl asked the librarian, “Do you have anything about machines that talk?”

The librarian was confused at first, until she placed a finger on what Julia was asking about.

“Oh, you want to know about computers!”

She handed Julia a couple of books, but they weren’t much use to a girl who couldn’t read. After flipping through pages of dense text, Julia returned to the shelves to find something more visual. She hit paydirt with a bound volume containing pictures of early computers. The photographs mesmerized the child: all those beeping machines, some of them taking up entire rooms.

But nothing prepared her for a photograph tucked away toward the back of the book. It wasn’t of a machine, but of a man. A man whom many historians regard as the pioneer of computer algorithms, the general-purpose computer, and a founding father of both theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence.

“The moment I saw his face, it was like I knew him. It was an odd feeling of extreme familiarity.”

“The moment I saw his face, it was like I knew him,” Julia recalls. “It was an odd feeling of extreme familiarity.”

Taking the book home, she kept the volume open to the picture for the duration of her library loan. Then she checked it out again.

When her mother caught sight of the book, she scoffed. “Who is this?”

So began a lifetime of teasing and misunderstanding over Julia’s reverence for Alan Turing. Julia just couldn’t articulate it. How to explain that this image felt alive to her? Somehow, she was bound to Alan Turing.

Soon, an image was not enough.

“My thought was, is Alan Turing alive? Because I would like to meet him,” she recalls.

Julia’s desire to know everything she could about Alan Turing propelled her to learn to read and write. That’s when she discovered that the mathematician had died in 1954, and that his legacy extended far beyond computers. In fact, Turing had even been an accomplished marathon runner.

Julia was inspired. Not only did she start excelling in school, but she followed Turing’s footsteps into track and field. The quiet girl whose family had told her she’d never amount to anything began to run. And run. And run.

“Soon I became the fastest runner in school,” she says. “My teachers couldn’t believe it.”

This run continued after Julia was put up for adoption and settled in with a foster family in Morro Bay, California. Going by the last name of Elliott (her step-father’s name) in high school, Julia began breaking regional track records, even running an 11.5-second 100-meter dash, according to the May 15, 1980, edition of the Sun-Bulletin newspaper.

She was propelled by a growing inspiration for Alan Turing. “He was my father figure, all the way up until I was nineteen,” she recalls. “Then it changed drastically from there.”

What happened?

“I fell in love with him,” she says.

Alan Turing was no longer her father figure.

“He was like a husband.”

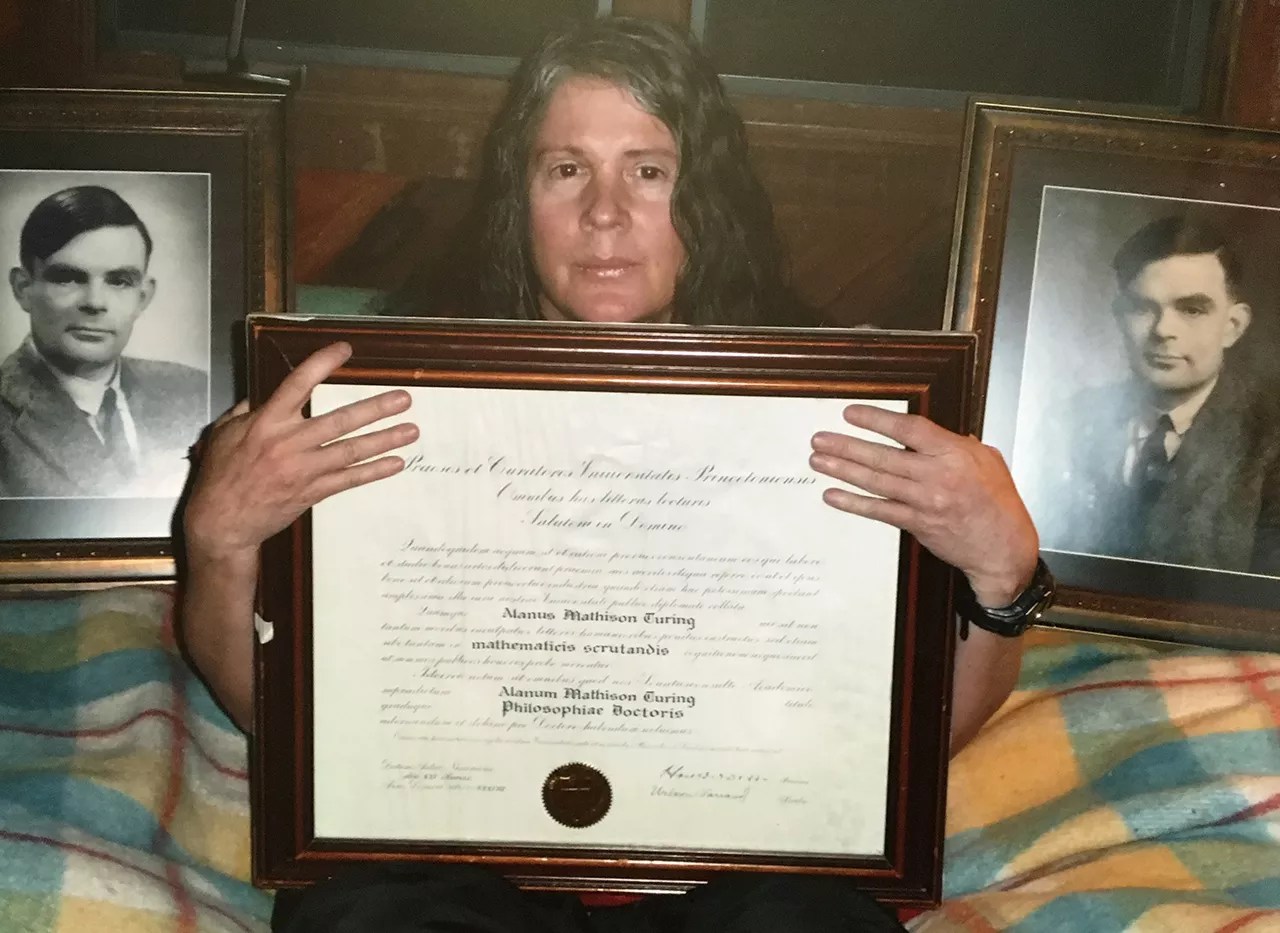

Julia Turing holding Alan Turing’s Ph.D. diploma in 2012.

Courtesy of Julia Turing

Although Julia felt intimately connected to Turing, she was disturbed by how little she knew of his personal life. But she was hardly alone in that regard in the 1980s. Alan Turing remained relatively obscure until 2012, when the British government declassified key documents that revealed the extent to which his code-breaking skills helped to undermine the Germans’ enigma machine in World War Two, changing the course of the war and giving the Allies a significant advantage over their Nazi adversaries.

“But back then there was so little information about him, and I was hungry to learn more,” Julia remembers. “For instance, I still didn’t really understand the situation of how he died.”

For details like that, Julia had to dig deep. She tracked down books from England and sought primary source material. That’s when she started learning that Turing had endured a tumultuous personal life of his own. It came to a head in 1952, when he was prosecuted for homosexual acts – then still a crime in the U.K. – after he had reported a petty burglary and had admitted to having a male lover in his house. After being found guilty of “gross indecency,” Turing was subjected to chemical castration. The English government forced him out of the secret service, and just weeks before his 42nd birthday, Turing was found dead at his home. An inquest found his death to be suicide by cyanide poisoning.

But in 1984, Julia – then 22 years old – only knew some of these specifics. To find out more about Turing, she decided to make a trip to England. She used money that an insurance company had paid her following a car accident to buy her plane ticket.

In England, Julia hit the ground running. She toured the universities where Turing had once walked the stone corridors, either as a student or a researcher. These included Oxford, Cambridge and King’s College. At each school, she requested to view any archived material available on Turing, but archivists and librarians were suspicious. Who was this American lady, and why was she so interested in Turing? Julia remembers being disappointed that her access was so limited.

She was about to give up on school archives when she remembered one more institution that Turing had attended from 1926 to 1931, when he was a teenager: Sherborne School, a prestigious, all-boys boarding school in Dorset.

It was here that Julia finally got access to the types of artifacts she was looking for. Turing’s mother had donated many items to the school between 1965 and 1967; they included things like Turing’s school reports, photographs, medals (including Turing’s OBE – Officer of the Order of the British Empire – which is similar to the Presidential Medal of Freedom in the U.S.) and school certificates, among them his Ph.D. diploma in mathematics from Princeton University.

“Back then there was so little information about him, and I was hungry to learn more.”

Julia was amazed to find herself face to face with so many important items from Turing’s life. These were things that he had held, had interacted with, had – even for a minute – contemplated and diverted some of his genius to. Julia felt Turing’s presence like never before.

Given Turing’s obscurity at the time, it wasn’t surprising that the Sherborne librarian told her that people rarely came to look at the Turing archive.

Half-jokingly, Julia responded, “Well, then, can I have it?”

What happened next all those years ago is at the heart of the recent legal mess. While the librarian did not give Julia permission to take any items, Julia also spoke to the school’s treasurer, Colonel A.W. Gallon.

According to Julia, Gallon confirmed that visitors rarely came to see the Turing archive. She says that after she shared her troubled life story with Gallon, including how Turing was so inspirational to her, Gallon told her that she could take Turing’s Ph.D. diploma, since it meant so much to her.

While there is no direct evidence to document Julia’s version of this conversation, there’s some evidence to suggest that Gallon later supported the idea that Julia could keep the Ph.D. But things get sticky from there, because Julia did steal from the school.

Julia returned to Sherborne after her initial visit to view the items a second time. When the librarian left her side and she found herself alone, the librarian’s comment about so few people caring to visit the Turing archive rang through her mind. Her heart raced as an irrepressible urge welled up.

“I made a mistake,” Julia says. “I was young. I felt that Alan Turing’s things were in danger because no one really wanted them and they were just sitting there. So I made a mistake. I took some items.”

According to a memo written by Gallon after he retired in 1989, Sherborne wasn’t aware of the theft until Julia contacted the school soon after her visits.

“I did not see her again but she wrote expressing her joy at having a collection of Turing items, and included photo of them laid out on a table – his photo, OBE & so on,” Gallon wrote. “I was not aware that she had taken them, nor indeed was the librarian! I asked him [the librarian] to make a list of the missing items but it proved to be incomplete because we had no inventory anyway…I gave up any hope of ever getting A.T.’s things back ’til one day she wrote saying she was sending them back. A parcel arrived. It contained more than the Librarian had listed which made me cross.”

Both Sherborne and Julia saved some of the correspondence between her and Gallon – which recently became exhibits in the government’s case in Colorado.

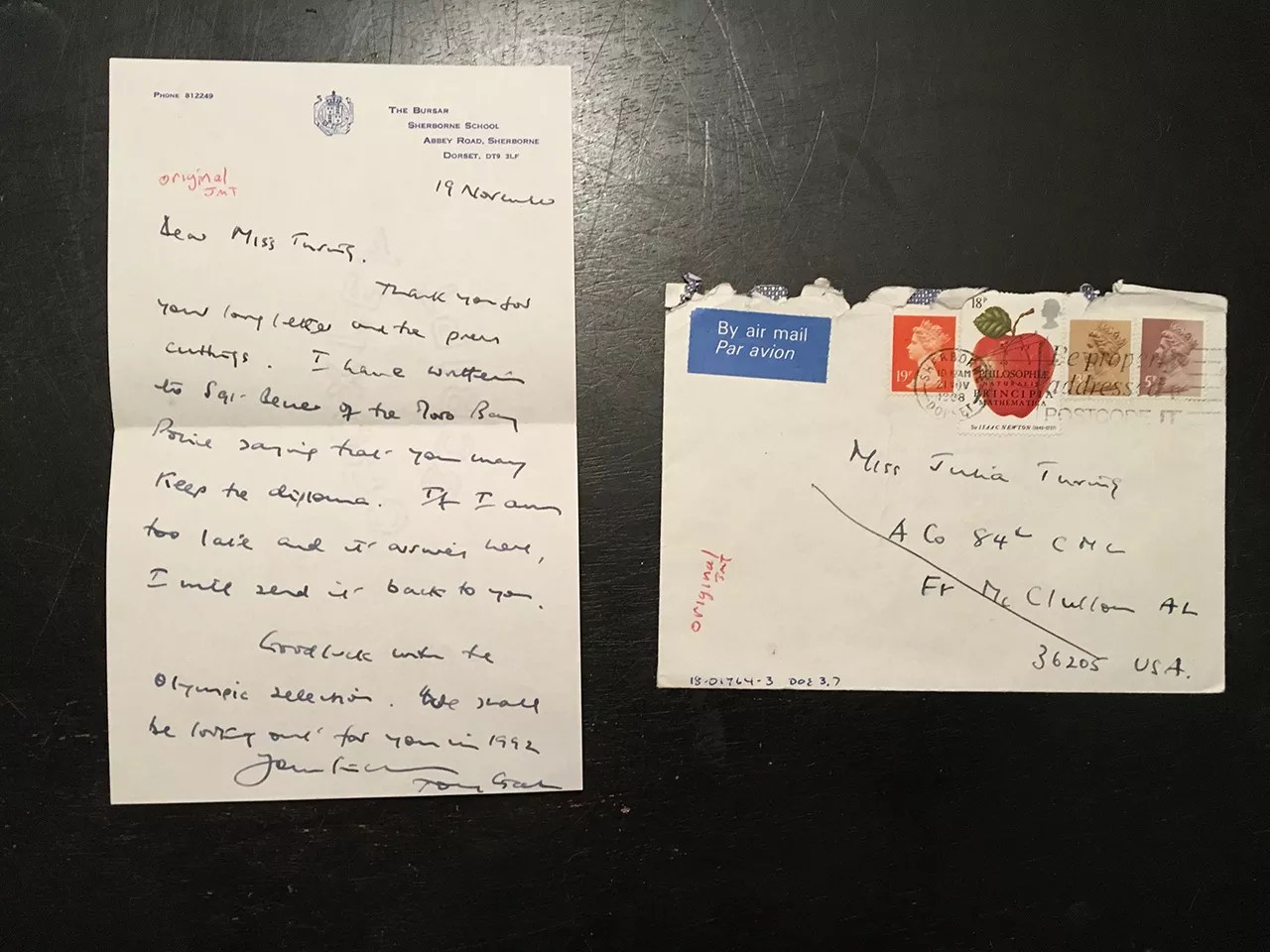

A letter to Julia from Colonel A.W. Gallon.

Courtesy of Julia Turing

After returning many of the items to Sherborne – indeed, more than the school’s librarian knew existed – Julia wrote: Please forgive me for what I did. I know what I did was wrong….I want you to know that it was very hard for me to steel [sic]. For I have never stolen before in my life and did feel very badly for taking them.

Gallon appeared sympathetic. In a letter dated August 7, 1984, he wrote:

Dear Miss Schwinghamer,

I do hope that I have your name right…If the Turing memorabilia arrived safely then all will be forgotten as far as we are concerned. I think I can understand how you have felt and what motivated you is an action out of character with your normal self. Thank you for phoning. It was such a great relief for us when you chose to respond, and I repeat my invitation to come and continue and research in the future.

On August 20, he followed up to confirm receipt of the items, while noting that Julia did not return one photograph.

Dear Miss Schwinghamer,

You will be pleased to know that the parcel arrived safely and I am grateful to you for what is a very [illegible] gesture and one of which Alan Turing [illegible] would be proud. I am sorry that you have retained the one photograph. Particularly as there was a negative among the collection from which you could have had another one done. I have now [illegible] here, and because of your action, you may keep the photograph. I have told the police here that you have returned all but the photograph and that as far as we are concerned, the matter is closed. I hope that they will pass this on to the police there, but you will have this letter to show them in case you are questioned.

Julia seemed to have taken the words “the matter is closed” at their fullest implication.

What Gallon likely didn’t know (his letters and memo never mentioned it) was that Julia still had a number of items, including a miniature version of his OBE medal. For Julia, after Gallon declared the matter closed, it seemed that anything she still had of Turing’s was rightfully hers. Once again, his spirit had come through their cosmic connection and made everything work out. Her love for Turing only grew.

Sometime in early 1988, Julia legally changed her name to Julia Mathison Turing, in a play off of Turing’s father’s name, Julius Mathison Turing. “I was done with being bounced around from place to place and from name to name,” she explains. “I took his name because I thought it was appropriate. He saved my life.”

The name change was reflected in Julia’s next correspondence with Gallon. Because despite matters being “closed” in 1984, Julia needed his assistance again a few years later.

The bizarre episode occurred in late 1988, when Julia had a domestic dispute with a foster sister, Carol Elliot, with whom she was again living in Morro Bay. Carol and Julia had always had a contentious relationship.

According to Julia, Carol thought she was a freak because of her adulation of Alan Turing, and she knew how important the Turing artifacts were to Julia.

After an argument over Carol’s boyfriend, whom Julia threatened to report for alleged criminal behavior, Carol took Turing’s Ph.D. diploma and a couple of his photos to the Morro Bay Police Department and told the cops that Julia had stolen them from Sherborne School in England.

After phoning the school, the police sent the diploma back to Sherborne.

On September 15, 1988, Julia wrote Gallon, pleading with him to return the diploma to her:

I am sure that Alan is as sorrowful as I am over my terrible loss of his Ph.D. If there was only some way you could understand just how much Alan means to me. I believe maybe you would allow Alan’s Ph.D. to remain with me until I would eventually return it as I had promised, because you have shown me your generosity to me [sic] before.

Incredibly, Gallon seemed swayed by Julia’s letters and decided to send back the diploma. On November 19, he wrote:

Dear Miss Turing:

Thank you for your long letter and the press cuttings. I have written to Sgt. Beuer of the Morro Bay Police saying that you may keep the diploma. If I am too late and it arrives here, I will send it back to you.

Authorities in Colorado located these letters, along with a customs declaration from Britain, that seem to support this twist in the story: Gallon did gift the Ph.D. diploma – along with a couple of Turing photos – to Julia. In fact, rather than being angry with Julia, Gallon even said that he was rooting for her success as an officer in the U.S. Army and as a standout track-and-field star:

Good luck with the Olympic selection. We shall be looking out for you in 1992.

At least Gallon wasn’t being misled about Julia’s career accomplishments. They were unbelievable yet true.

Julia Turing won six gold medals at the 1991 Armed Forces Championships.

Courtesy of Julia Turing

“Faster than a private dodging his platoon sergeant, speedier than an M-16 on rapid fire, able to leap the Headquarters building with a single bound, look out Flo Jo, here comes Lt. Turing.” U.S. Army writer Cliff Jackson wrote that at the start of an April 11, 1990, article titled “The Champion” for the newspaper that served Julia’s Army posting in Stuttgart, Germany.

The piece continued: “2nd Lt. Julia M Turing is one of the 11th Chemical Company’s platoon leaders. How fast is she? In a 200 meter dash her average time is 22:88; when you compare that time to the world class time of 20.5, that’s nothing to sneeze at.”

More than a dozen newspaper articles document Julia’s career record as a track star. They range from coverage of her accomplishments in high school (fourth in California’s state finals) to winning the 100, 200 and 400 meter races in the 1988 Community College State Championships in California. After completing her higher education at Arizona State University, Julia donned a uniform for the Army and continued running as a member of the Armed Forces. In 1990, she was named the military’s “Service Athlete of the Year.” Stars and Stripes noted that she was “the sixth fastest sprinter in the U.S.A.”

With headlines like “Against All Odds” – that one from the Star Presidian of San Francisco – articles took note of her difficult upbringing and overcoming the challenges of being shuttled between foster families. One article also mentioned that an “Allen A. Turing” [sic] was Julia’s inspiration.

But then duty called, and Julia’s running career took a break as the U.S. military prepared to invade Iraq. A lieutenant in the Army’s Chemical Company, Julia was stationed in Saudi Arabia during Operation Desert Storm, where she briefed incoming soldiers on possible sources of chemical attacks from Saddam Hussein’s forces.

Julia worried that her deployment would hamper her quest to represent the United States at the Olympics, but after returning from the Middle East, she won six gold medals at the 1991 Armed Forces Championships, breaking a 39-year military record for the most gold medals at a single event.

She was at the peak of her training when she arrived at the Olympic trials in Barcelona, Spain – the final, qualifying event for the 1992 Olympic games. But she also arrived in the Catalonian capital with multiple running-related injuries. Reporters wanted to know: Could she push through it? Julia said that she would try to overcome any pain and give “101 percent,” just as she had at the 1991 Armed Forces Championships.

But as the deadline approached, Julia’s foot was killing her. She finally got it X-rayed, and doctors found that she had broken it in two places. Her right leg also had stress fractures.

“You can’t compete,” doctors said. “If your leg breaks, you’ll never walk normally again.”

Julia attempted the 200-meter race anyway, but had to pull up before she rounded the first turn. Her running career was over.

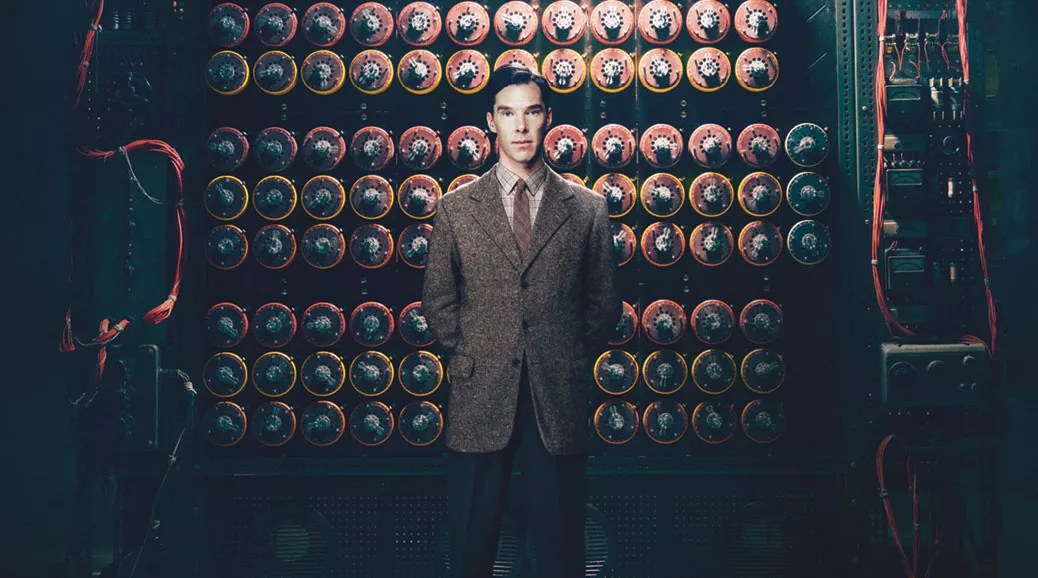

Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing.

The Imitation Game

After the first Gulf War, the Army downsized. With little use for a chemical warfare specialist, Julia was placed on reserve, she says. She decided to leave the Army and work a low-level job for the Department of Justice instead – the job that brought her to Colorado. While living on the Front Range, Julia continued to collect and sell Turing-related artifacts and memorabilia. She set up an eBay page where she offered Turing artwork she’d made using oil pencils on heavy pressed paper. But she stayed out of the limelight, working various service jobs, including restaurant work, after she left the justice department in the late ’90s.

Then came the movie.

The Imitation Game was a complete game-changer for someone who had dedicated much of her life to Alan Turing. While Julia isn’t particularly fond of the film – she noted various inaccuracies – she was pleased to see Turing get the recognition he deserved. The British government even apologized for how it had treated Turing; in 2013, Queen Elizabeth II granted Turing a posthumous pardon for his “indecency” conviction.

Then in early 2018, Julia saw a news story about the University of Boulder science department putting together an exhibit on important figures in science history. “I thought, ‘Oh, I’ve got this [Turing] collection, and now that Alan Turing is starting to be recognized and known, why not share?,'” she recalls.

She phoned the head of special collections and archives at CU Boulder, who encouraged her to come to the campus with her Turing artifacts. (When Westword reached out to the archivist, CU referred all questions to the U.S. Attorney’s Office.)

According to court documents, Julia presented herself to the archivist as a daughter of Alan Turing – a claim Julia strongly denies. “How could I be his daughter when he died seven years before I was born?” she asks. The CU archivist checked out Julia’s claims that certain artifacts – the Ph.D. diploma among them – were authentic. And when the archivist reached Sherborne School in England, officials there said that the items had been stolen by an American woman in the 1980s. The CU archivist then reached out to law enforcement.

Julia remembers February 16, 2018, as being a cold day. It had snowed the night before, and she was at her home in Conifer when she heard a knock at the door. An officer from Jefferson County was on her doorstep.

“Is your car okay?” the officer asked.

According to Julia, the officer said that he’d been getting reports of vehicle break-ins in the area and wanted to check on her car. She assured him that her car was just fine.

“As soon as I stepped out of the door, SUVs came rolling in.”

“Then he put his foot in the door and insisted I come out,” Julia says. “As soon as I stepped out of the door, SUVs came rolling in.”

The officer in charge deposited a search warrant at Julia’s feet as he walked past her. Julia claims that she was made to stand outside in below-freezing temperatures as federal law enforcement agents rooted through her home.

She says that she heard glass smash and laughter, as well as one officer yelling, “Hey! Anyone want to order a pizza?”

Documents from the U.S. Attorney’s Office suggest that Julia was evasive during the search. Turing’s Ph.D. diploma was found hidden behind a dresser. Officers discovered a removable section of wall underneath some stairs, where a leather briefcase containing other Turing artifacts had been tucked away.

At the time of the search, U.S. officials did not know of the letters that Julia had exchanged with Gallon in the 1980s – including those in which he appeared to give her permission to hold on to certain photographs and the diploma. But Julia also had other Turing items in her possession, among them a miniature OBE and a letter from King George VI. When U.S. authorities reached out to Sherborne, the school was able to locate the original inventory of items that Turing’s mother had supplied the school – a document that Gallon and the librarian had failed to consult in 1984.

After the search, the U.S. Attorney’s Office spent some time unraveling the complicated story of the items that Julia had collected – some apparently gifted, some stolen. Nearly two years passed before the U.S. Attorney’s Office issued a formal complaint against Julia: a civil asset forfeiture case (a type of litigation most commonly used in drug-related cases, which essentially argues that the government can keep property it took in a search).

Even then, the office did not charge her criminally.

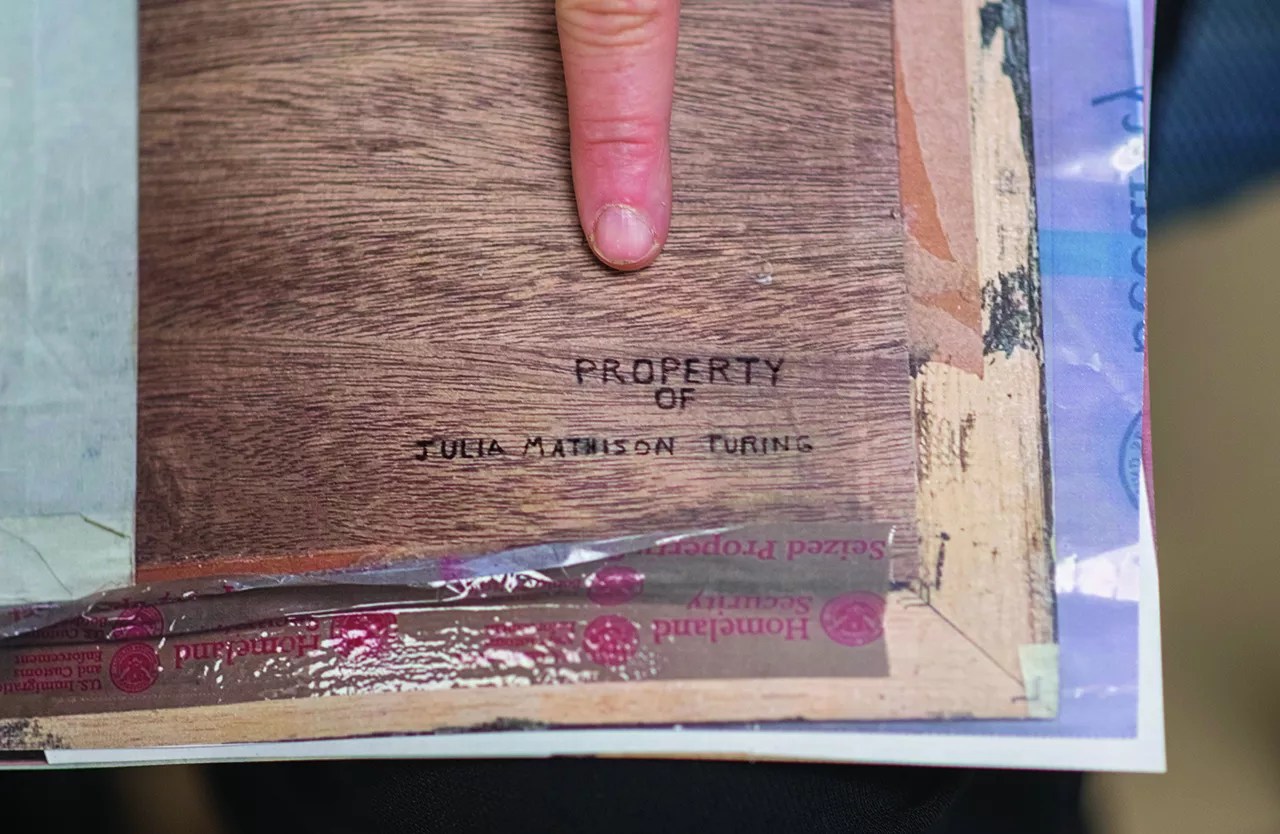

The inscription on the back of the diploma indicates that it was once Julia’s property.

Evan Sem

The court of public opinion did not take as nuanced an approach to her case.

After the Boulder Daily Camera ran a story about the government’s formal complaint against Julia Turing in January 2020, news outlets around the world picked up the story.

“FBI recovers WWII codebreaker Alan Turing’s personal possessions 36 years after they were stolen by a woman who claims to be his daughter from his British boarding school,” declared the Daily Mail, a U.K. tabloid.

Julia says that friends stopped talking to her after they read the articles. She’d been so traumatized by the search of her Conifer home that she’d moved to a town in southern Colorado to get away from the bad memories. It’s been a lonely and stressful time for someone whose closest companion – Alan Turing – felt most alive to her through the items of his that she possessed.

At first Julia contested the government’s civil asset forfeiture, hiring a lawyer in Atlanta to try to get the items back. But she says that the government’s opposition, as well as pressure from Sherborne School for the items’ return, was fierce. “I think now that a movie’s been made about him, anything Alan Turing goes on the auction block for millions of dollars,” she says. “I think that [Sherborne] realized my collection was worth a lot of money and they wanted it back.”

Julia’s not wrong about the increasing valuation of Alan Turing memorabilia. In April 2015, a wartime manuscript of Turing’s mathematical notes sold for $1,025,000, and the following February, a letter signed by him fetched $136,122.

“I think now that a movie’s been made about him, anything Alan Turing goes on the auction block for millions of dollars.”

The Sherborne School archivist referred Westword to prior comments that the institution had made about the case, including this one from Headmaster Dr. Dominic Luckett: “We are sorry that by removing the material from the school archives, Ms. Turing has denied generations of pupils and researchers the opportunity to consult it.”

Actual blood relatives of Alan Turing have expressed relief that the artifacts were located. “To find out that items were squirreled away in mysterious circumstances, by someone who had no right to them and kept them out of the public realm, and for them now to be returned, is a really positive and good thing,” Sir Dermot Turing, a nephew, told the BBC.

Even with the Gallon letters as backup, Julia eventually saw the writing on the wall: She wasn’t going to get the Turing items back. “My attorney said that even if I win my case, all [the government] will do is appeal,” she says. “One appeal after another. So basically, I don’t have a chance of getting my stuff back.”

Julia even gave up on getting items back that she says have nothing to do with Alan Turing, like war medals belonging to her grandfather and great-grandfather. “Through bitter tears I decided, well, maybe it’s better that I let [the items] go back to England, where it can be in an archive,” she explains.

Deeming her lawyers worthless, she canned them in late 2020 in favor of negotiating a settlement herself. That settlement, which was reached this past April, releases the government from all claims for damage to Julia’s home and for her attorney’s fees (which Julia is shouldering and says are significant).

In a conciliatory note, the government did appear to acknowledge that the Ph.D. diploma was gifted to her – just without Sherborne School’s permission. “Item number 8: Claimant Julia Turing recognizes that defendant Diploma, Princeton University, Ph.D. in Mathematics, issued to Alanum Mathison Turing, among other defendant assets, were gifted to her by an individual, A.W. Gallon, as Bursar of Sherborne School, who did not have the authority to have provided the items to her,” court documents note.

“Although not a party to the Settlement Agreement, Sherborne School has stated that they will display a plaque stating that defendant Ph.D. was in Ms. Turing’s care from 1984-2020,” according to the documents.

Once the settlement was reached, Acting U.S. Attorney Matt Kirsch sent the following statement to Westword:

“Together with our partners at Homeland Security Investigations, the U.S. Attorney’s Office is proud to have obtained an order of forfeiture for several historic items associated with Alan Mathison Turing. Alan Turing was a pioneer of computer science whose work deciphering the ‘Enigma’ code significantly aided the Allies’ efforts during the Second World War. Obtaining the forfeiture of these historic objects is an important step in ensuring that they can be returned to the Sherborne School in England, Mr. Turing’s alma mater, where they can be shared with the public for years to come.”

More than three years after the search executed at her home, Julia’s long, strange journey with Turing’s artifacts was finally coming to a close.

But not before she would get a last look at what had been her most prized possession: Turing’s Ph.D. diploma.

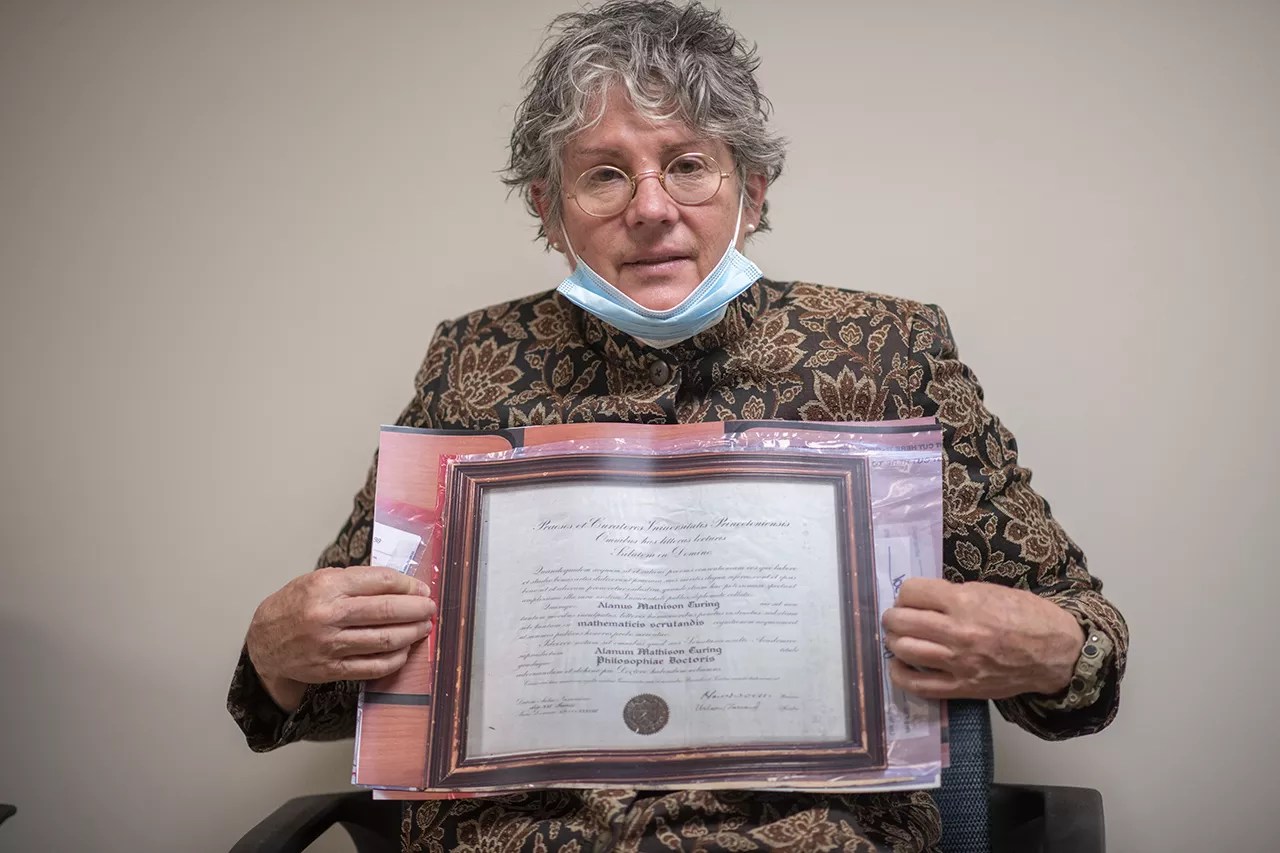

Julia Turing at the U.S. Customs and Border Protection office on May 25 with a copy of Alan Turing’s Ph.D. diploma.

Evan Sem

As part of her settlement, Julia had negotiated a thirty-minute viewing of the Ph.D. diploma before it was shipped off to England. A photographer would be allowed to take high-resolution pictures of the document so that she could have a printed copy to keep.

All eyes were on Julia when she entered the Customs and Border Protection office on May 25. After hours in her car, crying, she looked tired. She’d cut her graying hair short, a new look, and all of the stress – not to mention a couple of medical emergencies after her legal troubles began – had taken a toll on her health.

The guards, lawyers, archivist and photographer all followed her movements with rapt attention. No one had actually seen her with the Ph.D. diploma before, and as soon as Julia caught sight of it, presented on a padded surface, she seemed to enter a trance.

On an iPad that she was allowed to bring into the room with her, she started playing a specific selection by Bach – Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor – just as she had innumerable times before. It was part of the ritual. The song seemed to encapsulate Turing’s genius, and the Ph.D. diploma was a physical embodiment of the man that Julia loved.

At one point, she reached toward the Ph.D. to caress it. A security guard grabbed her arm before she could get any closer.

“I’m not touching it! I’m not touching it!” Julia yelled.

When the song ended, she started it again. At one point, the photographer tried to get her to look at his camera’s viewfinder. “Is this okay?” he asked. Julia was crying so hard she couldn’t see anything.

It was all so much. She reminded herself that after this, she’d just have to keep breathing and take her days one at a time. She leaned in close to the diploma.

“I love you. I have always loved you,” she whispered.

At exactly thirty minutes, a guard barked. “Time’s up.”

He made Julia stop the music.

Passacaglia and Fugue still had a minute left.