Denver East Golf Club/Monika Swiderski

Audio By Carbonatix

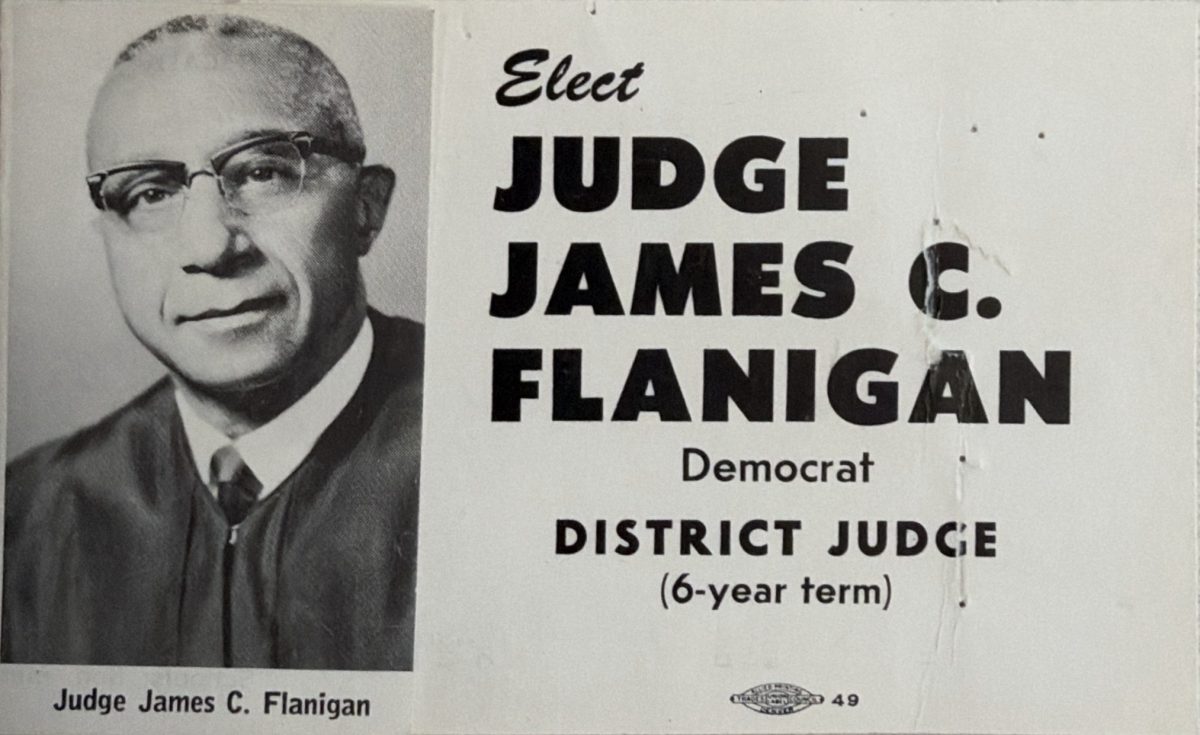

Judge Flanigan’s courtroom was out of session on Monday, August 7, 1961. His honor had a 10:12 tee time.

Flanigan was set to make his debut in the Colorado Golf Association Match Play Championship at Cherry Hills Country Club, where a year earlier, Arnold Palmer had overcome a seven-stroke deficit to win the U.S. Open. But when Flanigan arrived at the course, he was prohibited from walking on the first tee. Seeing the judge, executives from the CGA told him to go home: “Negroes are not allowed.”

The CGA had an official policy of recognizing only the oldest private club that counted Denver’s public courses as its home, which kept membership all-white. Flanigan was a member of the East Denver Golf Club, an all-Black club he’d founded almost two decades earlier that played out of City Park Golf Course. After chastising the district court judge for not divulging that he was Black when he registered for the tournament, the CGA executive admitted the organization normally didn’t think about asking registrants their race. “If we allowed you to play,” Flanigan was told, “we’d be shut down.”

A few days after Flanigan’s rejection at Cherry Hills, another East Denver Golf Club member, Jerome Biffle, made a tee time at Park Hill Golf Club, the daily-fee golf course a few blocks northeast of City Park. Although Biffle and his friends had played the course before, the foursome was turned away this time. After barring Biffle, a local high school teacher and guidance counselor, from teeing it up, the starter declared golf was a “gentleman’s game and we want to keep it that way.”

Flanigan and Biffle had exposed institutional racism in Denver golf. Their challenge to the barriers placed between them and certain tee boxes was years in the making, and these episodes occurred against the backdrop of civil rights demonstrations by Freedom Riders across the South, which had been constant throughout the summer. However, neither Flanigan nor Biffle was an activist, and it’s unclear if they deliberately set out to change the course of golf.

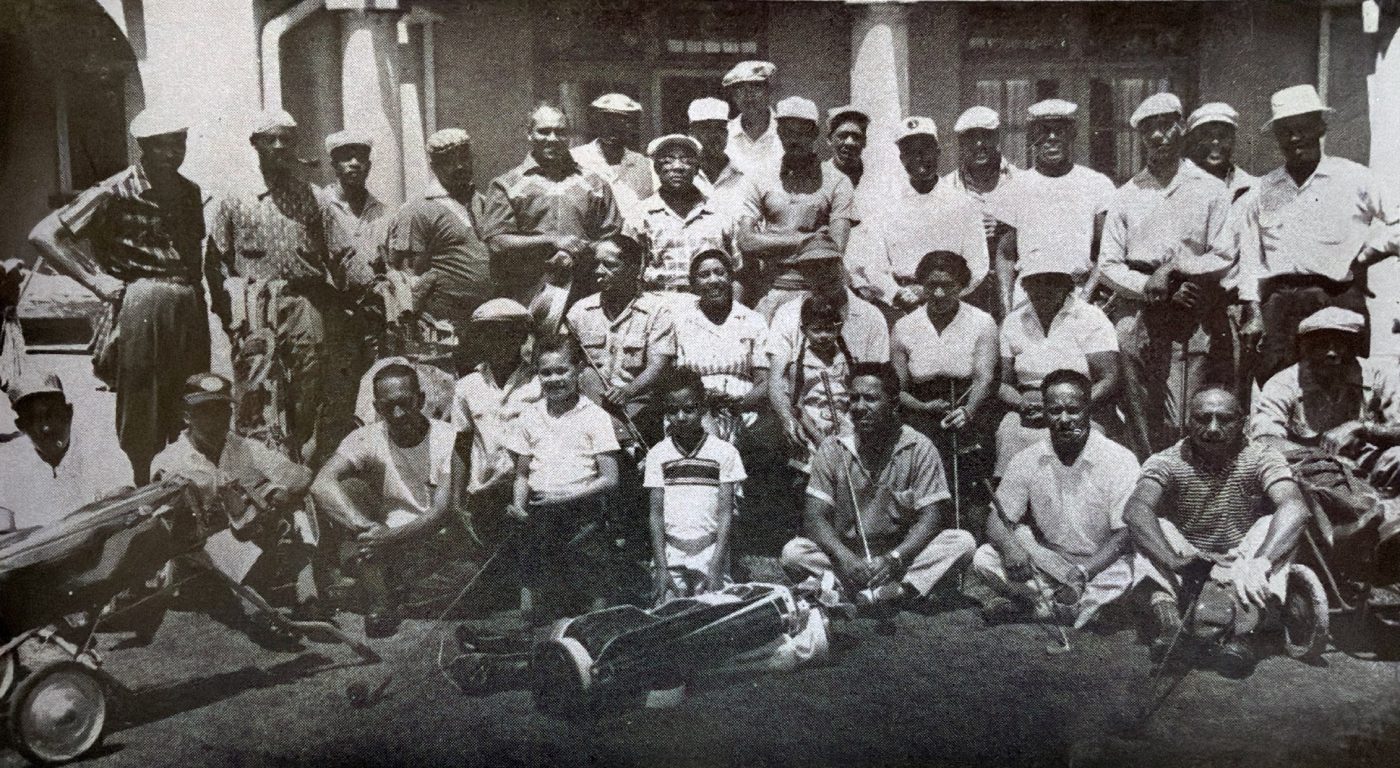

Denver East Golf Club

Flanigan was so intent on following protocol that he ordered his court staff to wear gray jackets, which he purchased for them, to maintain “the dignity of the courtroom.”

Biffle, who grew up in the neighborhood, was surely aware of Park Hill’s reputation when he crossed Colorado Boulevard to make a tee time, though. “Negros are generally not refused rental of the ballrooms and bars,” an East Denver Golf Club member had written earlier in 1961. “They patronize the dining hall for lunch, etc., but the course cannot be played.”

Park Hill Golf Course was built on land formerly owned by George Clayton, Denver’s largest property owner in the 1860s, a decade before Colorado became a state and a hundred years before Biffle set foot on the property. Clayton amassed his fortune selling clothing, boots and mining equipment on Larimer Square. Upon his death, he left his property to the City of Denver in a trust “establishing, and forever maintaining a permanent college…[for] poor white male orphan children.” Before it was a golf course, the land was used as a dairy farm, part of the agricultural curriculum for the boys.

In 1930, an engineer and stockbroker named Bob Shearer leased the farm from the Clayton Trust, got rid of the cows, and turned the property into a golf course. Shearer, a member of Cherry Hills, hosted a week-long tournament every July that attracted big-name golfers, as well as a six-figure Calcutta: an open auction where gamblers buy into participants. Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and Babe Zaharias all participated in the event, as did heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, an exception to the policy that restricted Blacks from playing the course.

Flanigan and Biffle had navigated Denver’s spoken and unspoken rules of segregation for decades. When Flanigan founded the East Denver Golf Club, the Denver mayor’s office was occupied by Benjamin Stapleton, who’d been number 1,128 on the Ku Klux Klan membership. Stapleton had filled several city posts with Klansmen during his first term as mayor in the 1920s, including the parks manager who oversaw the municipal golf courses. By the end of that decade, the Klan was all but defunct, but discrimination remained.

To attract members for the East Denver Golf Club, Flanigan took out an advertisement in The Colorado Statesman in May 1945. “The East Denver Golf Club is going great,” he wrote. “It is growing larger by the day. I join the East Denver Golf Club in extending their invitation to you. Remember, young or old, rich or poor, you can learn to play this grand sport of golf.”

Flanigan recruited men from his neighborhood for the club. They were a collection of railroad porters, dentists, soldiers, firefighters and business owners, men with nicknames like Huck, Coochie and Gip.

“They competed at everything,” says Lawren Cary, the son of an East Denver Golf Club member, who still lives in a house neighboring City Park. “They had hunting clubs, ski clubs, bowling clubs. I remember them getting home from the course and staying up all night to play cards. When the sun came up, they walked back across the street to the golf course and went at each other there.”

To gain recognition as a bona fide organization, the East Denver Golf Club wrote to the United States Golf Association asking for guidance, drafted bylaws and set a competition schedule. Still, the club had trouble finding local competitions it could enter.

Flanigan to Five Points, Biffle from Five Points

James C. Flanigan, the backbone of the East Denver Golf Club, was born in either Fort Smith or Ozark, Arkansas, in 1914 or 1915. He was raised in Kansas by his mother, who instilled in him the importance of education. It was a value she learned from her father, a former slave nicknamed “Fess,” short for “professor,” because he could read and write.

Flanigan attended junior college and supported his family by working behind the fountain at the American Candy Shoppe at 123 West Myrtle Street in Independence, Kansas. When his wife, Luella, developed tuberculosis, Flanigan flipped through an almanac to find a city with a dry climate and a large Black population where he could continue his education. After lingering on Albuquerque, Flanigan scrolled through the B’s and C’s before landing on Denver.

Since the late 1800s, Colorado had been a haven for tuberculosis patients, whose lungs responded well to the aridity. While Luella recovered from her illness, Flanigan could continue his education and seek professional opportunities. Denver was a growing city with more than 6,000 Black residents by the late 1930s, most of whom lived in the Five Points neighborhood.

Denver East Golf Club

To get to Denver, Flanigan said he “hoboed” on a midnight train from Goodland, Kansas. At least, he hoboed for a while. It was January 1938, and the sleet and snow on the plains proved to be too much. By the time his train got to Limon, a little more than halfway to his destination, he conceded to the weather and purchased a ticket for $1.85 to secure a spot inside a train car for the rest of his journey.

Dubbed the “Harlem of the West” by Jack Kerouac, Five Points was a city within a city where Black-owned businesses lined the streets. Musical legends, including Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald, performed at the Rossonian nightclub on Welton Street. Heavyweight champions Joe Louis and Sonny Liston held court at Bishops Barbershop.

In Growing Up Black in Denver, Biffle said Five Points was “where everybody went, where all the action was and all the socialization; and if anyone bothered you, you’d report to the bartenders at Benny Hooper’s or ‘Knockout Brown’s,’ and they would take care of the situation.”

Social, political and professional clubs emerged, many with overlapping memberships. The Protective Order of Dining-Car Waiters #465 unionized to fight for better conditions for railroad workers. The Cosmopolitan Club was formed to combat racial and religious tensions. The Owl Club was founded to recognize academic achievement by young Black women. (The group would later honor Denver high school student, future Secretary of State and self-described “medium handicap golfer” Condoleezza Rice.)

Flanigan arrived at Union Station without knowing a soul in the city and rented a room at the YMCA until Luella could join him in their new hometown. He enrolled at the University of Denver and worked odd jobs as a postal worker and porter on the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad. After graduation, he was chosen for a special school at Lowry Air Force Base, a few miles east of Five Points, and later got a job as an associate economist with the War Labor Board. In 1943, Flanigan accompanied a friend who was applying to Westminster Law School. When the pair walked in the registrar’s office, the clerk persuaded Flanigan to submit an application as well. Although his friend later dropped out of the program, Flanigan was accepted. He had found his purpose.

At around the same time, Biffle was establishing himself as a standout on the East High track team. Biffle was all-city and all-state in four events. He also starred as a halfback on the East High football team, leading the Angels to an undefeated record and state championship in 1945. He was the son of Denver’s first Black fire captain, who worked at station No. 3, the only firehouse in Denver where African-Americans could work, and one of the busiest in the city. As a student-athlete, Biffle faced Jim Crow whenever his team left Denver for meets.

“He would tell us about when his teams traveled to tournaments,” says Ed Mate, whom Biffle later coached on the East High golf team, “and when the hotels would see Jerome Biffle, they would say, ‘You can’t stay here,’ and the rest of the team would say, ‘Well, if he can’t stay here, we’re not staying here.’”

At the University of Denver, Biffle was called a “one-man track team” because he competed in the 100-meter, 220-meter, long jump, high jump and relay team. In 1950, he was named the top college track athlete in the nation after winning the broad jump in Kansas, Modesto and Fresno track meets.

After graduation, Biffle enlisted in the Army and prepared for possible deployment in the Korean War. “I laid off track altogether after going into the Army,” Biffle told a reporter in 1951. “Then this spring I thought I’d like to have a go at the Olympics. So I started working out in April, and the first time I jumped I pulled a muscle.”

Denver East Golf Club

Despite the rust, Biffle managed to finish second in the long jump at the 1952 Olympic qualifier, which was good enough to earn a spot on the U.S. roster.

On a rainy day at the Helsinki Olympic Stadium, wearing a white USA track uniform and bib #1020, Biffle found himself in second place after his first two attempts, trailing fellow American Meredith “Flash” Gourdine. On his third attempt of the day, Biffle leaped 24 feet, 10.3 inches — below his personal best, but nearly two inches ahead of Flash. It was enough to win the gold medal.

“It was one of the grandest feelings possible,” Biffle wrote in a letter to his mother, “to stand on the winner’s platform and accept my gold medal beneath the Star-Spangled Banner.”

Returning to Colorado, Biffle was greeted with a hero’s welcome at the airport and awarded the Denver Dollar, an old Mile High iteration of a key to the city.

Later that year, Biffle received the Robert B. Russell Award as the Rocky Mountain Region’s outstanding athlete and was selected to stand alongside his idol and mentor Jesse Owens in the Drake Relays Hall of Fame. Governor Dan Thornton called Biffle “a great sportsman and a true American.”

Growing the East Denver Golf Club

However accomplished Flanigan and Biffle were in their respective fields (and tracks), they were not insulated from the omnipresent racism of their hometown.

“When we moved to Denver from Midland [Texas], I remember being excited about leaving a city in the South that was so segregated. My parents were domestic workers. All the Black folks literally lived on one side of the railroad tracks,” recalls Tom Woodard, a local golfing talent who caddied for Flanigan and Biffle at City Park. “When I got to Denver, though, it was more of the same. There were more professional opportunities, but it was still a segregated city.”

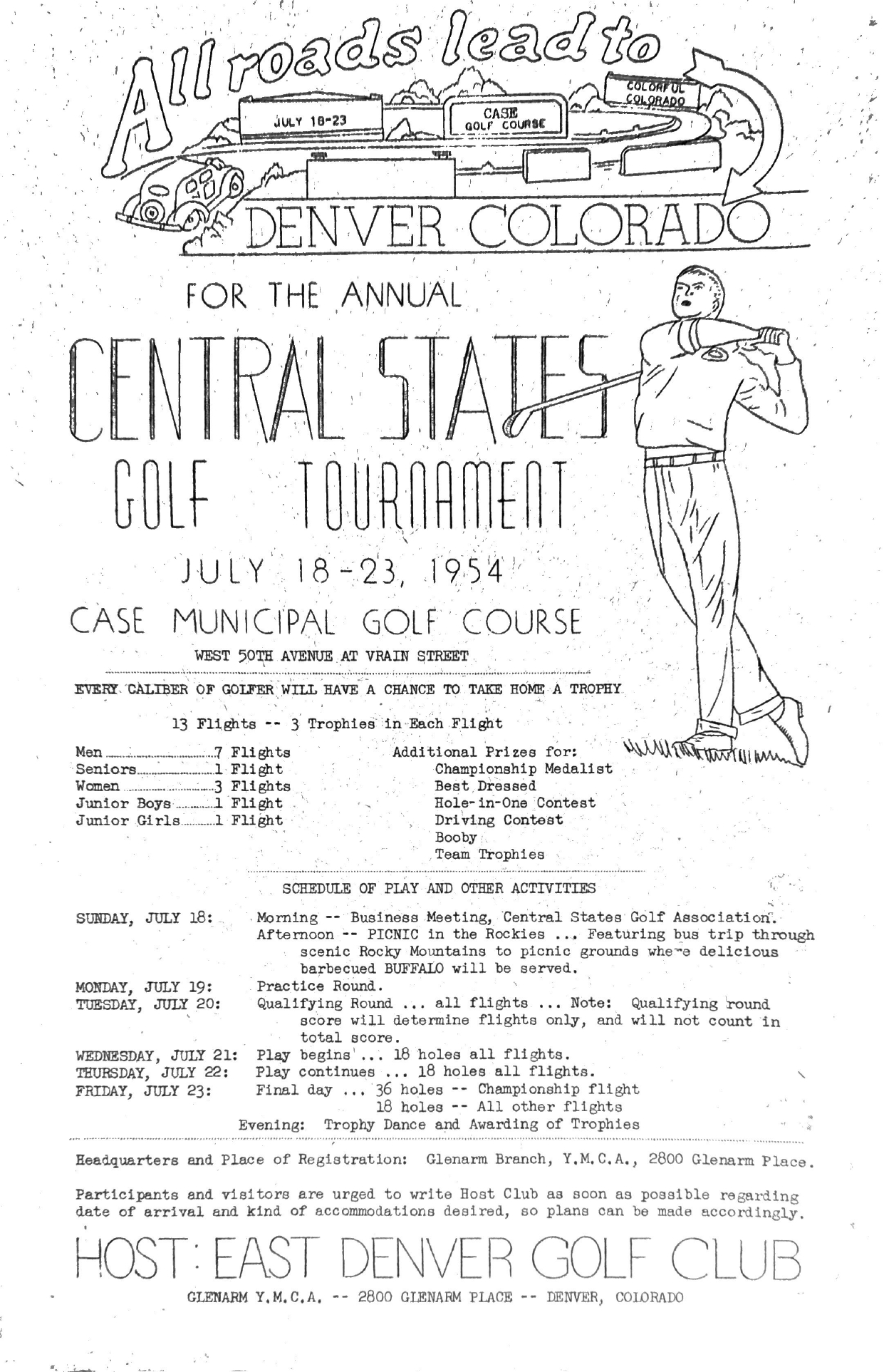

When Flanigan inquired about membership in the CGA for the East Denver Golf Club in the 1940s, his application was rebuffed by CGA executive N.C. “Tub” Morris, a history teacher at West High School. Without legal recourse to challenge the private organization’s membership standards, the East Denver Golf Club set up matches with other minority groups also ostracized by the CGA, such as the local Japanese club, and joined the Central States Golf Association (CSGA), a collection of Black clubs from around the Midwest.

The CSGA was one of a handful of golf associations, such as the Western States Golf Association and United Golfers Association, that offered Black golfers a chance to compete against other Black golfers. When the CSGA was founded in 1931, municipal golf in America was segregated, and accessibility for Black golfers was subject to the politics of their city or state. There were 700 municipal golf courses in America, but fewer than twenty were open to Blacks.

In 1947, the East Denver Golf Club was picked to host the CSGA Championship, an annual gathering of clubs from Des Moines, Kansas City, Omaha and other Midwest cities. The club worked with Mayor Quigg Newton, who’d succeeded Stapleton, to secure Wellshire Golf Course for the event. Newton was more amenable to working with the East Denver Golf Club than the previous administration, and Wellshire was the most prestigious municipal course in Denver, one of the few Donald Ross course designs west of the Mississippi River. The CSGA tournament would serve as a trial run for the PGA Tour’s Denver Open, which was won by Ben Hogan at Wellshire the following year.

With Flanigan serving as secretary of the club, the East Denver Golf Club established committees to divide and conquer the responsibilities of running such a big event. A Housing Committee was established to secure safe housing for their guests. The Entertainment Committee, with help from member Leroy Smith, a record store owner, secured Ernie Fields and his Orchestra to play a private show for their guests at the Rainbow Ballroom. A handful of club members’ wives comprised the Scoring Committee. Benny Collier, a law clerk who was part of Flanigan’s regular Sunday foursome, was the eventual winner of the tournament, establishing the East Denver Golf Club as a perennial force among CSGA clubs.

Hosting the tournament turned out to be a pivotal moment for the East Denver Golf Club. The joy and camaraderie members found in the regional gathering launched the club into growth mode. Shortly after the tournament, and perhaps influenced by other CSGA organizations, the East Denver Golf Club inquired with the USGA about proper procedure for establishing a women’s division, and created a free junior program to ensure that future generations would be exposed to golf at no cost to their parents.

“When we moved to Denver, we moved literally two blocks from City Park. Seven kids in my family…you ain’t getting no allowance with seven kids. So, I went down to the golf course to caddy and shag balls,” recalls Woodard, a member of the East Denver junior club who later spent a few years on the PGA Tour. “This junior program that got me into golf was run by the East Denver Golf Club and was 100 percent free. You didn’t pay a penny…I spent all my time at the golf course. I ventured down there to make money, but it was all over when I started playing. I was out there golfing my ball.”

When Denver next played host to the CSGA tournament, in 1954, America was in the early stages of a golf boom. President Dwight Eisenhower was perhaps the most famous golfer in the world, and attracted national attention to golf in Denver. Along with Augusta National, where he played frequently during his presidency, Eisenhower’s other home course away from home was Cherry Hills, about ten miles south of Mamie Eisenhower’s parents’ home.

Ike was at Cherry Hills the weeks before and after receiving the Republican nomination in 1952. He vacationed in Denver his first three years in office, when a typical day started with the president handling official duties out of Lowry Air Force Base in the morning before playing Cherry Hills in the afternoon, with matches arranged by club pro Rip Arnold. In 1953 alone, Eisenhower played sixteen rounds of golf in Denver. During another trip, Ike suffered a heart attack the morning after playing 27 holes at Cherry Hills.

While golf was growing in popularity, Black golfers were fighting for equal playing opportunities. In the wake of the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which established that segregated facilities were unconstitutional, Alfred and Dr. Hamilton Holmes, a father and son, demanded that Atlanta integrate its golf courses. After an initial ruling in their favor that set aside certain days of the week when Blacks could play, the Holmes family questioned whether they should accept limited access at the expense of full integration, and there was dissent among their supporters as to how far the Holmeses should push the case.

Future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, serving as the director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund at the time, was skeptical of devoting resources to a case about golf. Like others at the organization, he believed the case would benefit a privileged few and would take the NAACP away from its core mission.

“As the suit headed to the Supreme Court, it became clear that Marshall was wrong: vigorous reaction from both whites and blacks made Holmes v. Atlanta far more than just a case about ‘a few doctors,’” wrote Lane Demas in Game of Privilege. “Instead, it was one of the first instances in which all Atlanta citizens confronted segregation in post-Brown America.”

Finding a Solution

After Biffle was turned away from Park Hill, his foursome filed a complaint with the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission alleging Park Hill practiced a policy of discrimination “based on race and ancestry.” Shearer, who operated the course, was named as a defendant along with the Clayton Trust, which still owned the land. Because the mayor was a trustee for the estate, Biffle’s attorneys argued that the land was subject to the city’s anti-discrimination laws, which prohibited public facilities from refusing service to Blacks.

The Colorado Committee to Oppose Discrimination implored the mayor to act. “It is true that access to golf facilities may not be as serious as in the other areas but, because athletics and sports have generally been first to open doors to persons of all races and creeds…we were deeply shocked and troubled by the recent incidents in which some of our citizens were denied equal golf opportunities,” the group wrote.

The committee’s acknowledgement that golf was not as “serious” as other areas was reminiscent of Thurgood Marshall’s position, yet the CCOD worried that reports of discrimination at the height of tourist season would give visitors the wrong impression of Colorado.

Mayor Richard Batterton instructed City Attorney Robert Wham to investigate; he wanted to understand his liability as mayor and did not want to be an accessory to discrimination at Park Hill. In addition to Biffle’s case, the mayor was aware of Judge Flanigan’s rejection by the CGA and was sympathetic to his cause, although he did not have jurisdiction over the private organization. Batterton had a professional relationship with the judge and was set to reappoint him to the bench the following month, and the swearing-in ceremony might be uncomfortable if the situation was not resolved.

Ed Mate, Biffle’s former student, is now the head of the CGA. He says the organization missed a warning that would have helped it avoid the controversy that erupted after Flanigan was turned away. During one of his many roles at the organization, Mate interviewed Denver golf historian Dan Hogan about the incident. Hogan, who was White, played most of his golf out of City Park alongside Flanigan, Biffle and other members of the East Denver Golf Club. Before the 1961 tournament, Hogan was invited to address the CGA Board of Governors at Denver Country Club.

Denver East Golf Club

“My purpose was to see if they might consider membership for the East Denver Club in the Colorado Golf Association,” Hogan said. “They didn’t think it was a good idea. I told them…they might reap a whirlwind about that and it could have been avoided. They were a well-organized club with as much right out there as Wellshire’s men’s club or City Park’s men’s club to be a part of the Colorado Golf Association, but they didn’t feel it was the proper thing to do at this time.”

As Hogan predicted, word of Flanigan’s rejection soon spread around the country.

“This is part of our history,” Mate says. “It’s not something that we’re proud of, but we need to be honest with ourselves. This is part of who we were. Part of what society was.”

Denver Rabbi Robert Hammer dedicated a sermon to Flanigan’s plight. “A Negro cannot play golf on the sacred links of Cherry Hills Country Club?” Hammer said from the bimah. “There is no reason for this and there is no excuse for this.”

The Denver NAACP mocked the CGA by honoring the eventual champion, Sam Valuck, as the “Caucasian Amateur Golf Champion of Colorado.” Rip Arnold, the Cherry Hills pro who arranged games for Eisenhower, wrote Flanigan a letter of apology.

Meanwhile, City Attorney Wham held a series of meetings with a delegation representing the East Denver Golf Club that included former State Representative Ike Moore, Flanigan’s old law partner, and law clerk Benny Collier, Flanigan’s frequent golf partner. The East Denver emissaries made the recommendation that legislators enact a policy barring discrimination on municipal golf courses. Wham secured sponsors on Denver City Council, and in November 1961, Ordinance No. 316 passed unanimously, making it unlawful to knowingly conduct a golf tournament if any participation is known to be denied because of race, creed, color, national origin, ethnic or religious consideration.

Wham suggested to Batterton that the recommendations be followed in conjunction with holding informal talks with the CGA, and not as a substitute. It’s unclear whether such talks materialized, but the CGA Board of Governors dropped its ban on Black clubs the following month and approved the East Denver Golf Club as its newest member. The CGA President said the board “felt that our responsibilities to all of the citizens of Colorado should be paramount and override any private or selfish considerations.”

Passing the Baton

Woodard, whose first set of golf clubs and shoes were given to him by Flanigan, became the first Black man to make the finals of the CGA Championship. He credits the East Denver Golf Club not only with getting him started in golf, but with supporting him financially for his first few years as a professional golfer.

“I said at ten years old, ‘That’s what I want to do for a living.’” Woodard remembers. “‘I want to go to the golf course every day and play golf,’ and I did it.”

After his career as a professional golfer ended, Woodard returned to Denver to work as a golf professional, eventually rising to Director of Golf for the City of Denver. Inspired by the junior program that first exposed him to the game, Woodard established the city’s First Tee program that provided instruction to hundreds of local children.

Mate, who has known Woodard for years, also dedicated his professional career to expanding golf opportunities for Denver youth. After working his way up from intern to head of the CGA, Mate created the Golf in Schools initiative, which works with local schools to provide instruction on-site.

“Schools are desperate for these types of programs,” he says. “When we show up with instructors, equipment, thoughtful curriculum that is safe and fun, and you see kids that never even knew what a golf club was hitting that ‘birdie ball,’ you just see that big smile on their face of that shot euphoria that those of us who fell in love with the game have all experienced.”

Like Woodard, Mate caddied at City Park as a kid and earned an Evans Caddie Scholarship at Boulder. His proudest accomplishment as head of the CGA is its Solich Caddie and Leadership program, which now has four chapters in Colorado.

The Denver Inquirer/Denver East Golf Club

“Boulder is not exactly the most diverse city,” Mate says, “But if you walk in the Evans Scholarship House and look at the composite, you would see women, men, Black, White, tan, because of the Colorado Golf Association. …We have a diverse population. The Ethiopian Community, the Hispanic Community, has just been incredibly connected to this program, and we have now become the primary path to receiving Evans Scholarships in the state of Colorado. As a direct result of that, the Evans House went from 98 percent White men to 50 percent women, and men and women of all colors. If I do nothing else in my tenure at the CGA, I’ll feel pretty darn good about that.”

Even if they had not challenged Denver golf’s racial barriers in 1961, Flanigan and Biffle would have impacted generations of local golfers and put clubs in the hands of an untold number of kids who would not have been exposed to golf without the influence of the East Denver Golf Club.

“[Biffle] didn’t try to coach us much in golf, but he was certainly a life coach,” Mate says. “At practice, he would get us started and then drive his Cadillac up to the fourth tee and he would stand on the tee box, and he’d have these Wilson Staff Pro Staffs in sleeves and if we hit the green, he would give us a golf ball. …Sometimes he’d play with us. He’d go out and join us and we played for fictitious money. I once owed him $20 million.”

Although the East Denver Golf Club faded away in the 1980s, its members remained a fixture at City Park. Flanigan and Biffle’s friendship spanned parts of six decades. In 1997, when Tiger Woods won the Masters, Flanigan invited his old golf buddies to celebrate.

“I had the fellows over to the house, had them bring some barbecue and catfish,” Flanigan told the Denver Post.

“We sat there and were just overwhelmed.’” Biffle added. “I was delighted to see him win that, and do as well as he’s done. It opens a lot of doors for Blacks. I think you’ll find more and more Black kids taking up golf because of him.”

Biffle died of pulmonary fibrosis in 2002, but the former long jumper lived long enough to touch the Olympic torch one last time as it passed through Denver on its way to the Games in Salt Lake City. After his death, members of his blood family and golf family spread his ashes at City Park. Despite multiple bypass operations, Flanigan played regularly at City Park into his eighties. He died in 2008, a few years before the Lindsey-Flanigan Courthouse, named in part after the pioneering judge, opened in Denver.

In 2018, Park Hill Golf Course shut down indefinitely. The Clayton Trust sold the land to developers who sought to turn the golf course into a commercial real estate venture, but a conservation easement placed on the property dictated that the land remain green space. Despite ballot proposals and litigation seeking a lifting of the easement, the property remained an empty, dystopian shell of a former golf course for years, with “Keep Out” signs dotting the perimeter. In early 2025, Mayor Mike Johnston announced that the city had agreed to a land swap to acquire the property and end the stalemate; last month, the park reopened at least partially as open space. Money from the just-passed Vibrant Denver bond package will help complete the former golf course’s transformation.

Around the time the Park Hill Golf Course closed, City Park Golf Course underwent a massive renovation, part of a flood-mitigation plan to make the course more sustainable. As Woodard envisioned, the new layout includes a dedicated four-hole course for juniors. The clubhouse atop the hill provides a view of the city skyline beyond the neighboring Five Points community, with the Front Range and the Rocky Mountains in the background. A display in the lobby includes a brief history of the East Denver Golf Club, with photos of a young Tom Woodard receiving instruction in the junior program.

“Tub” Morris, the former CGA executive who told Flanigan the CGA would not accept Black clubs, was inducted into the Colorado Golf Hall of Fame in 1974. Bob Shearer, the owner of the Park Hill Club, was inducted in 1996. Woodard was formally inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2012, but notes that neither Flanigan nor Biffle is a member.

“That’s something I think must be addressed,” Woodard says. “Those two men did as much for golf in this state as anyone else.”