Colorado Parks and Wildlife

Audio By Carbonatix

After a dramatic discussion on June 12, the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission will have a special meeting about wolves before its next regular meeting on July 17.

Though wolf reintroduction wasn’t even on the agenda for the commission’s June meeting, wolves became a topic of contention after ranchers expressed extreme distress over the Copper Creek Wolf Pack during an open public comment session.

As a result, Commissioner Tai Jacober made a motion to remove the entire wolf pack, spinning the commissioners into a debate they’d hoped to avoid.

“I want to make a motion to remove the pack that is causing the problems. I hope it doesn’t have to be lethal, but that’s what I’m suggesting,” Jacober said.

Chair Dallas May wanted to immediately rule the motion out of order, as it hadn’t been properly presented – but other commissioners urged discussion of the idea, saying they felt like commission needed to take action.

“We’ve heard from the ag community at a rate that is starting to puzzle me, because I feel like we continue to hear and do the same thing over and over every month, hear the same type of comments every month, but have the same result,” Commissioner Murphy Robinson said. “I applaud Commissioner Jacober for his motion. The reason I applaud him is because it feels as though, like I said before, we’re a policy body and we have to try something and at least have a talk about something.”

Colorado is reintroducing wolves after voters approved a ballot measure to do so in 2020. Front Range populations voted for wolf reintroduction, but ranchers in the Western Slope, where the wolves have been released, did not. Since that vote occurred, ranchers and other agricultural producers have repeatedly expressed displeasure with wolves being reintroduced in Colorado, with many groups attempting to delay, pause or even repeal wolf reintroduction.

The Copper Creek Pack has caused problems since it was transported to Colorado from Oregon in late 2023. In 2024, the pack was connected to the deaths of a dozen sheep and cattle in Grand County. The adult male, which was responsible for those killings, died in captivity after sustaining a gunshot wound.

CPW subsequently captured the adult female and four pups, holding them in a wildlife sanctuary from late August 2024 until this January, when CPW re-released them in Pitkin County. The pack has added new pups this year, as confirmed by CPW earlier this week.

But the pack also added to its depredation count, being linked to four livestock attacks in eight days in May before CPW moved to kill one of the male yearlings.

At the June meeting, Chris Collins of the McCabe Ranch – where attacks by the pack were confirmed – said he doesn’t think removing the yearling is enough.

“We need to remove this pack,” Collins said. “We don’t want to see the wolves go away; we want to see the bad wolves go away.”

But Jeff Davis, CPW director, said that eliminating the bad wolves is exactly what CPW did by killing the male yearling. He defended CPW, pointing out that the agency created a definition for chronic depredation last year after being asked to do so by the agricultural community. Then, in June 2024, the agency used that definition to determine that the male yearling needed to be killed.

“I agree with people. Yes, last year was a perfect storm,” Davis said. “Hindsight is 20/20. I beat the crap out of myself every day for this situation. I’ll also remind us that these are endangered species still, and we don’t have sole management authority. How do I think that phone call will go to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to say we’re taking all of them out?”

Because wolves are on the federal endangered species list, Colorado had to apply for a special exemption to be able to use any control methods that could injure wolves, and can only kill wolves after consulting with U.S. Fish and Wildlife.

Davis insisted that CPW is monitoring the remaining pack closely, adding that he is certain at least one of the members of the pack has never been anywhere near a depredation incident. He said the rest of the pack has shown behavioral changes in the two weeks since CPW killed the yearling male, and added that he thinks it is appropriate to give the pack time.

“I say that with a huge respect to the producers that are going through this and our staff that are going through it with them,” Davis said. “I’m really struggling with the surprise motion.”

But others speaking up during the public comment session insisted that CPW’s timeline is lagging, including state Senator Marc Catlin, who represents the area where the Copper Creek Pack resides.

“I’ve got young men that look old in their eyes,” Catlin said. “They sound old because they’re looking down the road not knowing when this is going to be over, what it will look like when it’s all done. We need to address that. …One of the things that might help is that group of wolves up there in that den should be removed. I’m not sure how you want to do it. They should be gone.”

Producer after producer repeated the suggestion.

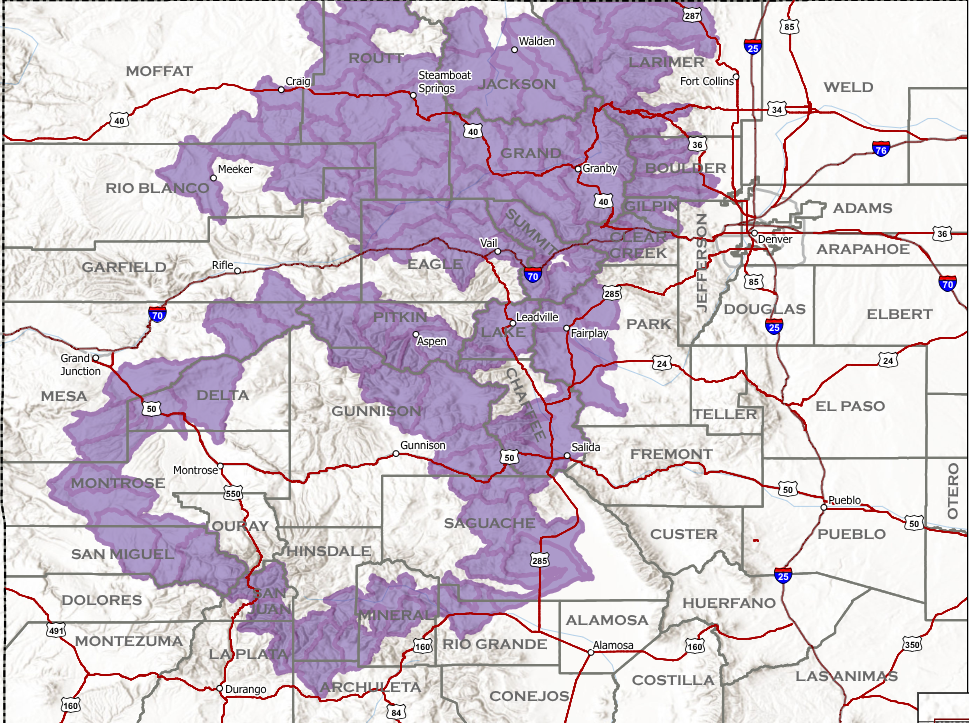

A map showing which Colorado watersheds wolves were in during May.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife

Several wolf and wildlife advocates pushed back, pointing to Colorado’s nation-leading Wolf Depredation Fund and new range rider program as evidence that CPW is doing what it can to help. Others said that the pups deserve to live beyond the six weeks or so that they’ve currently been alive, at the very least, as it is unlikely they’ve yet been depredated.

Mark Surls, Colorado state coordinator for Project Coyote, offered to lend manpower to help ranchers set up nonlethal conflict reduction measures.

“The act of taking this entire pack out would be egregious, in my mind,” Surls said. “Most likely, we’re dealing with three generations of wolves on the ground, and they haven’t had a depredation in over two weeks. Let’s give them a chance. … I don’t have a lot of money. We are a small NGO, but we can provide whatever we can.”

Others, like Commissioner Marie Haskett, said they don’t believe there are enough nonlethal reduction measures or funding available to prevent livestock deaths with wolves on the landscape.

“We need to support these people more than we are, and they’ve asked for help,” Haskett said. “There just isn’t enough resources out there.”

Commissioner James Jay Tutchton, on the other hand, said that he trusts Davis and the CPW staff are doing everything they can to make wolf reintroduction successful. Additionally, Tuchton pointed out that CPW has authorized ranchers to kill wolves immediately if they catch a wolf preying on their livestock, and has also okayed the use of night vision tools so that ranchers can observe their herds more closely.

“This is something that confuses me, because I hear, on ballot box biology, people say that decisions should not be made on emotion and they should not be made by just people that aren’t scientists,” Murphy said, in agreement with Tuchton. “Yet, we’re putting a lot of emphasis on opinions and emotion and not on the scientists. We’ve got some of the best scientists in the world working here, and I say, let them do their job.”

Still, Robinson insisted the commission cannot keep hearing the same complaints over and over and not take action. Therefore, Commissioner Eden Vardy suggested the commission have a special session to discuss the issue. Jacover agreed to amend his motion to call for such a meeting, clarifying that he wanted the wolves moved from Colorado but wasn’t necessarily suggesting they all immediately be killed.

The commissioners unanimously agreed to hold a special session on the wolf issue. CPW staff will begin preparing for that meeting and, in the meantime, Davis pledged to continue monitoring the pack closely.

“We’re trying to be incremental and strategic in our movements before we jump all the way to all of them are bad animals,” he said. “We are doing a ton out there.”

The CPW Commission’s next office meeting is scheduled for July 17-18 in Grand Junction; the special meeting will occur before then.

There will be plenty to talk about: Five of the fifteen wolves imported from British Columbia and released by CPW have died. According to the state’s wolf plan, if there is a survival rate of less than 70 percent six months after a release, the protocol should be reviewed. CPW has said the agency is waiting for necropsy reports from U.S. Fish and Wildlife to determine cause of death, but is also planning to assess translocation protocols.