Colorado Parks and Wildlife

Audio By Carbonatix

Colorado is eighteen months into the state’s wolf restoration project, and the teeth are still coming out.

So far, the state has paid over $370,000 in claims to ranchers who have been impacted by the presence of wolves near their operations. Although wolf advocates and detractors both agree that Colorado should compensate people for wolf-related losses, ranchers believe the funds are not enough to cover the full breadth of the impact of the carnivores in this state. Conversely, wildlife advocates question if some of the reimbursements that ranchers have claimed are a good use of taxpayer money.

The wolf-related claims that made many wildlife advocates howl came on December 31 from three ranchers in Middle Park. The ranchers argued the state should pay over $500,000 for wolf-related losses – but of that amount, less than $18,500 was for direct death or injury to sheep and cattle caused by wolves. The rest was for missing livestock, reduced weaning weights and fewer births at ranches with confirmed wolf attacks or kills.

The Colorado Wolf Restoration and Management Plan allows for compensation for indirect losses, but the amounts claimed exceeded what the state legislature had contemplated when it established the Wolf Compensation Depredation Fund, which receives $350,000 annually from the general fund.

Still, the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission unanimously approved almost $290,000 for one of the claims in March. That request, from Farrell Livestock, included $178,000 for reduced weights in over 1,400 calves and $90,000 for a 3 percent conception rate decrease compared to the three years prior to 2024. And that’s not counting an as-yet-unapproved claim by Farrell Ranch for $112,000 in missing cattle and another $100,000 claim from a rancher in Grand County. If those are approved, the 2024 allocation would be far overspent.

The 2024 budget was officially exceeded on May 8, when commissioners approved a $32,768 claim for two confirmed depredations on calves and fourteen missing calves; the commission will consider the remaining six-figure claims later this year.

“What we’re seeing is, ‘Wow, these claims are really big.’ They’re bigger than we’ve seen before, but we’re also trying to iron out the system so it’s fair and balanced to people and wolves,” says Samantha Miller, a senior carnivore campaigner with the Center for Biological Diversity who lives in Grand Lake.

Miller believes that if ranchers, wolf advocates and state departments continue to collaborate, the fluctuation in claims can be evened out.

Colorado is reintroducing wolves after voters approved a ballot measure to do so in 2020. State advocates began to push for reintroduction after waiting for years for the federal government to take action. When the feds failed to do so, advocates took matters into their own hands. Front Range populations voted for the idea, but ranchers in the Western Slope, where the wolves have been released, did not. The measure required reintroduced wolves to be on the ground in Colorado by the end of 2023.

The state’s wolf compensation program is the most generous of any state that has reintroduced wolves, but ranchers still believe the amount is not enough to outweigh the negative effects on their land and livestock.

There are only 27 known wolves roaming the state right now. This has caused wolves to act out of character, according to wildlife experts, since it is harder for them to form packs, hunt and establish territories. At the same time, ranchers worry about what will happen when there are more wolves.

“To me, that $350,000 is a drop in the bucket to what is going to happen when wolves get established and start covering the state of Colorado and having more depredations at scale,” says Andy Spann, president of the Gunnison County Stockgrowers Association. “That fund is underfunded, gigantically underfunded. It’s hard to put a number on what that should be when depredations start happening across the Western Slope.”

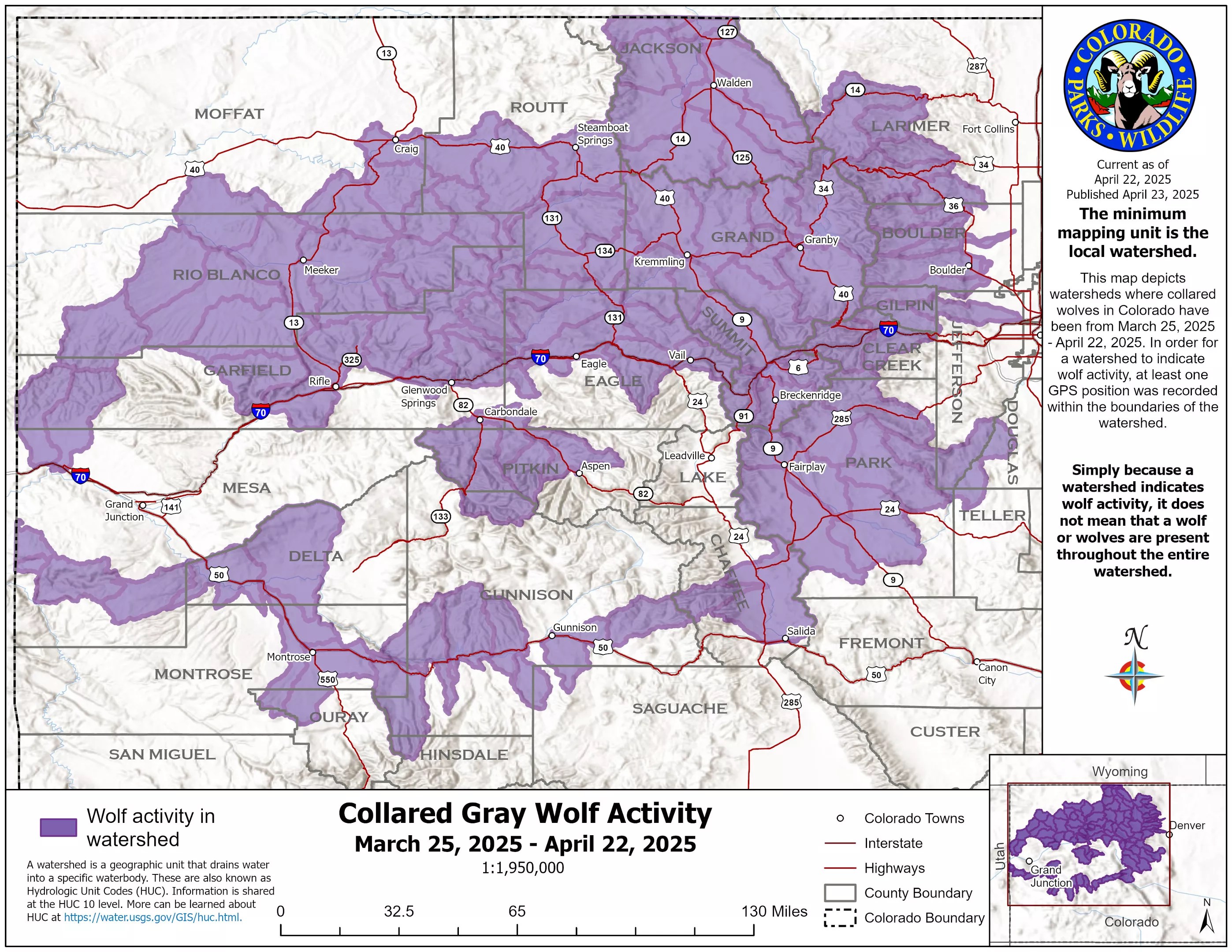

CPW’s wolf activity map shows all the water basins wolves have touched in the last month.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife

Ranchers can be compensated for low-weaning weights or low conception rates, according to Spann, but there are many more indirect impacts that could be considered, like the extra time and resources needed to deal with wolves or the emotional impact the situation has on ranchers. However, wolf reintroduction advocates worry that the lack of a standard to determine whether losses are actually wolf-related could lead to fund misallocation.

“What we need is objective and clear evidence that wolves are actually the cause of lower animal weights or fewer calves being born,” says Ryan Sedgeley, the southern Rockies representative for the Endangered Species Coalition. “We could just see the program getting depleted rather quickly.”

Through a spokesperson, CPW says all approved claims will be paid “from the most appropriate source available.”

According to Delia Malone, an ecologist with the Colorado Natural Heritage Program, while ranchers may be able to show that weights or conception rates were lower, there is still no way to prove wolves are the main cause.

“There really is no solid science that says the mere presence of a wolf will cause those so-called production losses,” she says. “They can correlate, but they cannot prove that a loss in weight gain or declining conception rates were due solely to wolves.”

Malone was stunned that the CPW commission approved the first claim in full.

“We are totally supportive of compensating for proven losses,” Malone says. “That’s not even a question, but this is so far out of the realm of reality and the realm of provability. …These folks are trying to claim that just the presence caused a loss of $200,000.”

Items like depleted food sources, disease, accidents, drought and other carnivores could also play a role, Malone suggests. According to USDA data, only about 0.01 percent of livestock losses in the country are due to wolves.

But Tim Ritschard, president of the Middlepark Stockgrowers Association, says ranchers keep logs of cattle weights and conditions each year, since they face huge losses in down years.

“We as producers consistently sell our calves every year, usually around the same timeframe every year, so we have an average of what our calves weigh at the time and we know what they should weigh,” says Ritschard, whose family has run a ranch in Kremmling for five generations. “When we have wolf activity and, all of a sudden, our calves are coming home weighing thirty to forty pounds lighter and yet, we have a really good year, there’s something going on.”

Ritschard didn’t suffer from wolf depredation or indirect issues himself, but says those in Middlepark who did could not identify any large change to the landscape this year other than wolves.

“People think that we’re just doing this,” Ritschard says. “We’re stewards of the land. …We take care of our cattle. We notice when the ground’s not producing as well, and so we cut our cow numbers, or we move our cows and allow that ground to rest and come back to what it was. We’ve been doing this forever. If we weren’t doing that, we wouldn’t be in business today.”

The first gray wolf was released in Colorado in 2023.

Endangered Species Coalition

As a middle ground, wildlife advocates have suggested requiring ranchers to 4use nonlethal wolf conflict reduction methods as a requirement for compensation. Through the Born to Be Wild license plate, the state has raised over $600,000 toward purchasing equipment for such strategies, but ranchers are only required to use the techniques if they are applying for a lethal control permit to kill wolves.

Current regulations allow ranchers to collect more money from the depredation fund if they used nonlethal methods to reduce conflict, but some believe the extra multiplier isn’t enough of an incentive. State Representative Tammy Story and Senator Kevin Priola sponsored a bill to require nonlethal methods in 2024, but the bill did not move past an initial committee hearing.

“That is still, really, in my mind, essential to make this a sustainable plan,” Malone says.

According to Sedgeley, livestock predation very rarely occurred when nonlethal techniques were deployed in other states with wolves.

“The presence of wolves can also impact how herds act,” Miller says. “So if we’re doing everything with nonlethals to keep wolves further away from cows, then sheep and cows don’t feel that stress or pressure of the animals around. That’s why I say nonlethals are the best, because they help both with direct and indirect losses.”

But Spann and Ritschard both vehemently disagree that any sort of nonlethal methods should be required for compensation. “To say we don’t get compensated because we didn’t mitigate for wolves? Absolutely not,” Spann says. “We can prepare as much as we want to. I don’t know how much it’s going to help.”

Both men argue that CPW has not deployed enough resources for nonlethal methods to enact such a requirement. According to a petition submitted by agricultural groups to the CPW commission last September, CPW should have paused wolf reintroduction until more systems were in place to support ranchers.

Ritschard, an advocate for the petition, told commissioners that ag groups wanted a range rider program to monitor areas in which wolves live, better carcass management, and site vulnerability assessments from the CPW, as well as a rapid response team for depredations in place, before any more wolves are brought to the state. The petition also requested a definition of chronic depredation so that wolves found regularly preying on livestock can be killed.

In December, CPW and the state Department of Agriculture announced that all of those suggestions would be implemented in the coming year. Parks and Wildlife has hired five wildlife damage experts with plans to hire more, and has also hired a Nonlethal Conflict Reduction Program Manager; the CDA has added two mitigation specialists. Now CPW is training range riders to deploy across the state, with fourteen ready for action.

As a result of that work, the CPW commission rejected the ag groups’ petition in January – but petitioners might have achieved a win last week thanks to a footnote in Colorado’s new budget, signed by Governor Jared Polis.

Polis approved a $2.1 million appropriation to be used on the wolf program, and he kept a footnote demanding the funds not be spent on bringing more wolves to Colorado “unless and until full and complete implementation of all state funded preventative measures discussed by the Parks and Wildlife Commission as part of its denial of a citizen petition to halt wolf reintroduction.”

Agencies are allowed to deviate from footnotes to the budget if necessary because they are not legally binding, but they typically comply. Ritschard believes complying is the right thing to do in this case.

“If you look at some of these other states, those programs were all in place, fully functional, before wolves were on the ground, and it helped,” he says. “We need to have that before any more wolves are on the ground, because otherwise we’re already going to see claims that are going to be the same, if not more than last year.”

A ballot measure to cancel wolf reintroduction in Colorado could hit voters in 2026 if a group called Smart Wolf Policy is successful. Smart Wolf Policy is currently collecting signatures for a citizens’ petition, but even ranchers and other agricultural producers are not in favor of the measure. A coalition of fifteen county commissioners, ranchers, hunters and wolf advocates joined together to send a letter to Smart Wolf Policy asking the group to pull its petition.

A wolf released in Colorado in January of this year.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife

The coalition argued that the petition would prevent the state from pausing reintroduction until the system is better equipped to handle wolves, as the ranchers and their supporters had asked in their denied petition to CPW.

According to CPW’s Travis Duncan, the agency has heard the “concerns and recommendations of all stakeholders,” and used that feedback to create an improved conflict minimization program. To showcase that work, CPW created a Wolf-Livestock Conflict Minimization Program Guide that shares tools and methods livestock producers can use; the guide also outlines how CPW responds to depredations.

“By working with and providing producers with this information and tools early, CPW hopes to reduce the potential of wolf-livestock conflict if wolves begin to spend time in the area,” Duncan says. “Having range riders out on the landscape this year strengthens our already strong conflict minimization program.”

Ritschard believes the range riders will be the biggest help of any CPW resource, but still feels Colorado dropped the ball.

On that, both wolf lovers and ranchers can agree.

“We weren’t quite ready,” Malone acknowledges. “Delaying that reintroduction until we had nonlethal methods in place would have been probably a better idea. …Now that we have range riders hired and ready to go, hopefully, that will be more palatable.”

At this point, given how early the state is in the reintroduction process, CPW is not considering changes to the wolf compensation plan. Through Duncan, the department notes that funding levels have met the needs so far.

Malone isn’t giving up on the idea that eventually nonlethal methods should be required for compensation, especially for ranchers claiming indirect impacts. Colorado still has plenty of time before a self-sustaining population of wolves exists here, which is required to fulfill the ballot measure.

“We have so many opportunities to not make the same mistakes other states have made and so many more opportunities for a collaborative approach,” Miller says. “Reintroduction is really tough, and it’s fraught with controversy, for sure. There are a lot of feelings on a lot of different sides, but at the end of the day…wolves deserve a space here, and programs like range riding and compensation help to carve out that space.”

This article was updated to correct an error stating that Delia Malone is vice-chair of the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project.