Jacob Frank/NPS

Audio By Carbonatix

More than two years after voters narrowly approved Proposition 114, which calls for reintroducing the gray wolf in the state by the end of 2023, Colorado Parks and Wildlife released the first draft of its long-anticipated Wolf Restoration and Management Plan.

The plan focuses on impact management and outlines measures that CPW can take to mitigate wolf conflict and help residents of Colorado, particularly ranchers, navigate the impacts of a reintroduced wolf population. “An impact-based approach recognizes that there are both positive and negative aspects of having wolves in the state,” Eric Odell, CPW species conservation program manager, said during a December 9 Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission meeting to discuss the nine-chapter plan.

“The greatest challenges associated with wolf restoration and wolf management are primarily going to come from social and political issues rather than the biological issues,” Odell noted. “Many aspects of the plan focus on this.”

To ensure that many voices were represented in the draft, CPW had assembled a Technical Working Group of reintroduction and management experts, as well as a Stakeholder Advisory Group of people from various geographic areas that might be impacted by wolf reintroduction.

According to Matt Barnes, a stakeholder member who’s been a rancher and worked to mitigate livestock-carnivore conflict in Montana and Wyoming before joining the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, Colorado’s plan – the first directed by voters at the state level – has the potential to be the most forward-looking, leading-edge wolf restoration plan in the country.

Chapter two, the longest chapter, identifies seven key elements for conservation and management: social tolerance for wolves and economic impact, wolf recovery, wolf management with respect to livestock interactions, wolf management with respect to wolf-ungulate interactions, wolf interactions with other wildlife species, wolves and human safety concerns, and monitoring and research.

The plan gets into specific details in chapter three: CPW will introduce thirty to fifty wolves captured from wild populations in the country over the next three to five years, depending on capture success, the cooperation of various partners, and the degree to which reintroduced wolves have survived and worked to establish a population.

“We want animals that are healthy,” Odell said, adding that while wolves have been introduced in other parts of the country, CPW would prefer to select animals from environments similar to Colorado’s, such as that of the northern Rocky Mountains. The agency will also look for animals that have not interacted with livestock. Once captured, the wolves will be transported to Colorado and released immediately, a practice called hard release.

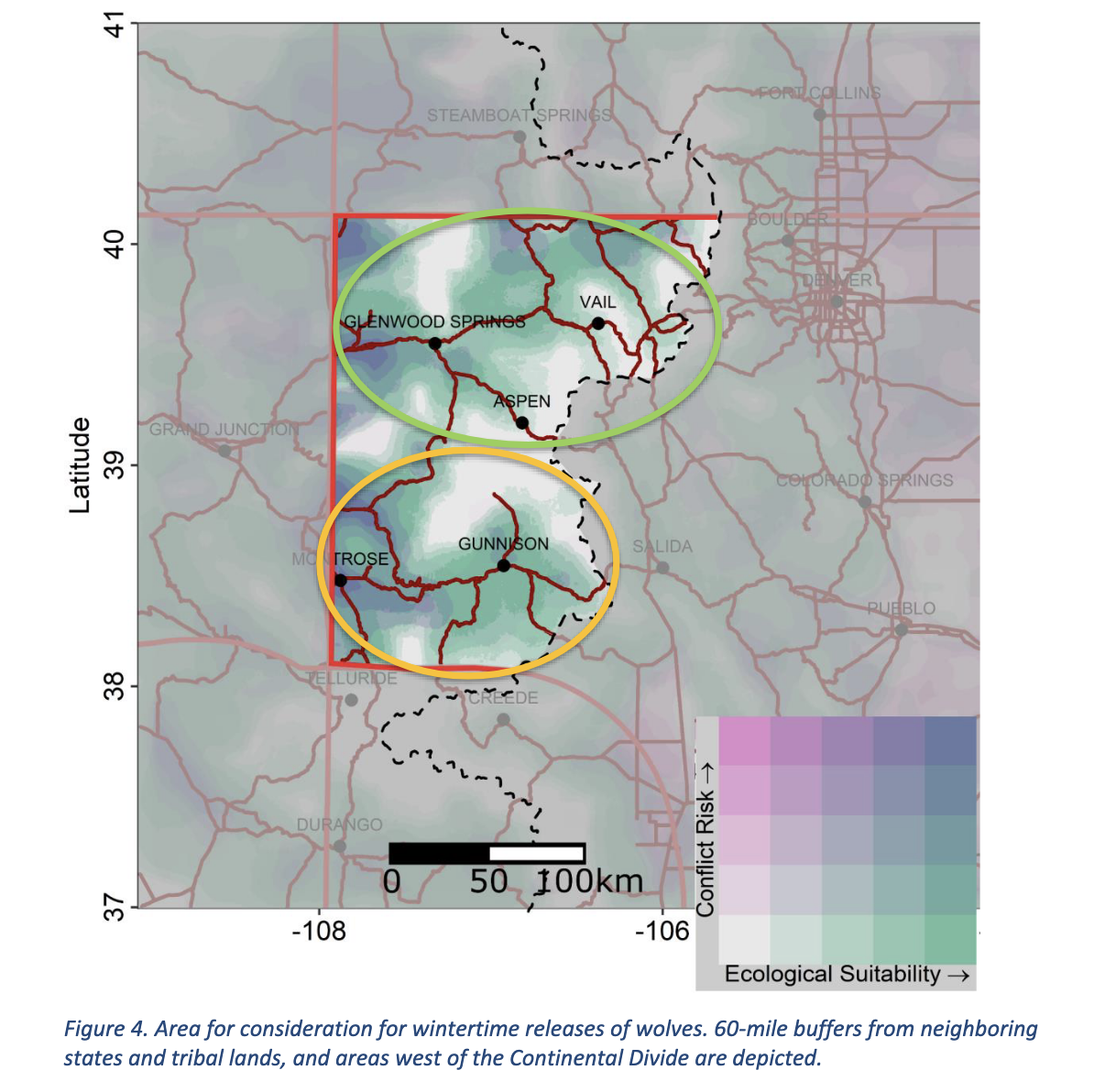

Releases will occur during winter months, and all of the animals will have GPS collars with mortality sensors. The first area to receive wolves next winter will be between the 39th and 40th parallels west of the Continental Divide near Glenwood Springs, Vail and Aspen on state or private land, with the full consent of the landowner. The plan does not consider releasing wolves on federal land.

Chapter four covers specific phases of recovery in accordance with where wolves sit on the state endangered species list; they have been categorized as endangered since 1974. “The idea behind the phased approach is that more conservative and protected management is employed when the population is smaller, potentially more vulnerable,” Brian Dreher, CPW terrestrial section manager, said at the meeting. “As the population grows, increased management flexibility can be afforded while remaining confident that the population status is secure.”

The first phase calls for a minimum count of fifty wolves in the state for four consecutive years before moving to the second, when wolves would be categorized as threatened in the state. In order to move to phase three, when wolves would be delisted as endangered in the state, there must be an annual minimum count of 150 for two successive years or 200 in one year.

“The important thing to understand is that recovery is really a continuum,” Barnes said after the meeting. “Eventually, we want to have a self-sustaining population. That’s a higher number of wolves than having enough wolves to delist them from the state Endangered Species Act.”

Although estimates vary, studies suggest the state could support about 1,000 wolves, Barnes added, and the biggest limiting factor to the wolf population would be human social tolerance and perception of the animals. Along with wolf advocates in the stakeholders group, he said he supported the addition of a geographical component to the wolf recovery metrics.

“The goal, eventually, is to have a wolf population exerting selective pressure on their primary prey species throughout western Colorado,” he explained. “In other words, we would like to see some wolf predation happening everywhere that elk are abundant.”

The green oval represents the area where wolves will be released first.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife

Could there ever be a fourth phase, when wolves are so abundant that hunting them is allowed? According to Barnes, that’s a philosophical issue. “The states that are doing it are doing it because people in their states want it, and I don’t think people in Colorado want wolves to be a game species,” he said. “The language in Proposition 114 defined wolves as a non-game species, and I think that was the voters’ intent.”

Though hunting isn’t a wolf management strategy, the plan contemplates a variety of other tools, particularly education. “Both non-lethal and lethal tools are often temporary solutions to resolve conflict,” Odell said at the meeting. “These tools are not implemented with the expectation that either of them will provide regular, long-term effectiveness. Non-lethal tools can be effective as a proactive preventative measure. These are techniques such as removing carcasses…utilizing range riders, aversive stimuli such as lights or noise, and other tools.”

The plan would allow non-injurious hazing at all times, and proposes to allow potentially injurious but non-lethal hazing such as rubber bullets at all times, as well. It specifies that lethal tools would only be used by federal or state agency staff, or someone with a limited duration permit if agencies don’t have the resources. Lethal management is useful in the case of recurring depredations, he noted, and most effective shortly after depredation occurs.

Only 4 percent of Montana’s wolves were removed through lethal control in 2020, according to Odell, and only one instance of lethal control occurred in Oregon in 2020. Even wolf advocates have recognized the need for occasional lethal control of wolves. A positive of Colorado’s plan is that it gives CPW discretion to determine when lethal control is appropriate while emphasizing that non-lethal methods are preferable, Barnes pointed out.

No potentially injurious or lethal control methods can be employed unless the state obtains a 10(j) plan under the Endangered Species Act with U.S. Fish and Wildlife. Since wolves are federally listed as endangered, such measures would be illegal without a specific exemption. CPW has already requested that Fish and Wildlife designate wolves as an experimental population.

During the December meeting, the part of the plan that received the most attention was chapter six, which deals with wolf-livestock interactions. The vote on Proposition 114 had shown a clear split between the Front Range and rural areas on the issue of wolf reintroduction.

Luke Hoffman, game damage and commercial parks manager for CPW, said that the agency will provide fladry – colored flags to deter wolves – and some scare devices to ranchers as needed. But conflict minimization techniques won’t be required before ranchers are eligible for compensation in the case of death, injury and indirect losses such as low weaning weights or low conception rates. Depredation confirmations will be made by CPW on a preponderance-of-evidence basis, meaning that the event was more likely to be wolves than not.

Compensation will be at fair market value and is capped at $8,000 per head of livestock. Veterinarian costs can also be covered; dogs will be compensated only if they were used for guarding or herding livestock. Because missing calves or young sheep are trickier to identify as having been killed by depredation, ranchers who have missing livestock under a year of age can be compensated for them if there is a confirmed depredation in the same band, herd or parcel as the missing young animal.

Ranchers can apply for a basic compensation ratio, which provides a more general compensation for missing or dead animals with less documentation, or itemized production losses, which provides for those situations and other indirect losses with more documentation required. Throughout the process of creating the draft, ranchers were insistent that indirect losses be part of the compensation plan. Wolf advocates were more hesitant to add such provisions.

“The way the system is set up, somebody could get paid for all of their missing cattle just because they had one wolf depredation, which is, to me, it’s a little bit problematic,” Barnes said. “It’s going to create a situation where people feel like it’s a handout to the ranchers and, to some degree, they would have a point.”

“There were some really good compromises,” says Renee Deal, who runs Sperry Livestock Corporation in Somerset with her family and was a member of the stakeholders group. “I don’t think anyone really got everything they wanted, but I think that that reflects the fact that it’s a compromise.”

The disagreement over compensation reflects how people view wolves philosophically as well as practically, making compromise difficult, according to Barnes.

“If you think that normal means being able to ranch with no wolves or that normal is the absence of wolves and that any loss caused by wolves is a cost of wolves coming back, then you would maybe develop a program like this where the intent is to compensate livestock producers for every conceivable loss,” he says now. “But if your idea of normal is the full suite of native wildlife, including all of the predators, and if you view human activities like ranching as essentially an add-on to that, then you start to think, well, some production losses are a cost of doing business.”

Chapter seven of the plan covers monitoring, ungulate management, research and reporting. CPW has a goal of collaring two wolves per pack for research, but given the difficulty of collaring, it will focus on collaring at least one member. It will also use hair and scat sampling and trail cameras to help indicate population abundance and monitor wolf health the way it monitors the health of other wildlife populations.

CPW will research everything from social tolerance for wolves to wolf ecology and wolf interactions with other animals, issuing annual reports as required by statute. Research findings will be included in those reports once they are peer-reviewed.

But Brian Kurzel of the National Wildlife Federation, a stakeholders’ member, says he wants to see clarification that CPW will use and share empirical data about social tolerance and attitudes toward wolves in real time rather than waiting for peer review, in order to be more proactive.

The final chapter of the plan concerns funding. Many programs in the draft don’t currently exist, and will need to be funded through the Colorado Legislature, at least temporarily. The goal is to find a long-term funding source outside of the political process.

Commissioners asked for specifics on how much funding would be required. According to Reid DeWalt, CPW assistant director of aquatic, terrestrial and natural resources, the agency needs some adaptive flexibility on funding but can share estimates at the next commission meeting.

The nearly 300-page plan released December 9 is still a draft, and the public will have the chance to comment in public hearings over the next several months; CPW has targeted the February 23 commission meeting as the final date to provide guidance to staffers for the final plan. A schedule of commission meetings is on the CPW website, and written comment can be submitted to wolfengagementco.org.

Deal encourages Coloradans to get involved.

“It’s been a challenging process, and it’s kind of put me way outside my comfort zone,” she acknowledges. “It made me feel like I actually was able to do something to help, because a lot of people on the Western Slope are really, really angry about the whole thing, and I was, too. It kind of helped me work through that anger and get to a place where I felt like we could actually come up with some solutions.”