Flickr/Eric Lumsden

Audio By Carbonatix

Criminal penalties for fentanyl possession implemented by a state law in 2022 did not lower preexisting trends of opioid overdose deaths in Colorado and may be associated with an increase among the Black population, according to a peer-reviewed report published in JAMA Health Forum earlier this month.

In 2020, there were a total of 919 opioid overdose deaths in Colorado and 64 deaths among non-Hispanic Black adults, according to the new report, which drew on data from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. By 2023, there were 1,157 total opioid overdose deaths overall, and 117 deaths among non-Hispanic Black adults, the new report says.

According to lead author Cole Jurecka, a researcher at the University of Colorado’s Anschutz Medical Campus, this report follows a longer examination of House Bill 22-1326, but with more data and analysis.

Introduced by former state legislators Alec Garnett, Brittany Pettersen, and John Cooke, HB 1326 had a contentious path through the General Assembly. After a law passed three years earlier making it a misdemeanor to possess up to four grams of most drugs, HB 1326 was billed as a correction to that law, according to supporters. Many Republican state lawmakers at the time thought the measure didn’t go far enough in increasing criminal penalties for fentanyl, while some Democrats were concerned it would just ramp up the war on drugs.

The new law’s provisions outline harm reduction and substance abuse treatment, but also elevated possession of one to four grams of any drug containing fentanyl from a misdemeanor to a level-four drug felony. That definition is important, as drugs like cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine can also be tainted with fentanyl.

There was also a provision in the law requiring the Behavioral Health Administration to hire an independent entity to study the public health effects of the newly increased criminal penalties, with Jurecka and his colleagues getting the call. The first report, released at the beginning of the year, found no reduction in overdose death rates associated with the law’s enactment. It also noted that “criminal penalties were perceived by participants as misguided in contrast to other approaches to stemming drug overdoses, including expanding access to medication, other treatment services, and criminal legal diversion options.”

The new report, with more data and more sources of data, concludes that the increased penalties did not change the preexisting trends for opioid overdose deaths in Colorado, and may have contributed to an increase in overdose deaths among the state’s Black population.

“We cannot attribute any causal effect to the bill on fatal overdoses,” Jurecka says. “We can say: this bill, one of the stated goals is to reduce overdose deaths. It did not do that, but there are a bunch of contributing factors to understand why it didn’t do that, outside of just the bill.”

José Esquibel is the director of the Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention, based at the University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Science. The Consortium has existed since 2013, and has been primarily responsible for coordinating the statewide response to the opioid crisis. Esquibel says opioid overdose deaths across the country, including in Colorado, were down in 2024, but the crisis is still on the upswing.

“When you take the 2020 overdose death and you cut out 2021, 2022, and 2023, and put it next to 2024, we’re still seeing an increase,” Esquibel explains. “Science has shown that harsher criminal penalties do not make significant changes in drug use patterns.”

Esquibel says drug use patterns are driven by cartels, which prey on drug users with the strategy of supply, addiction and demand. So if the science is clear that harsher criminal penalties don’t work, why were they included in the bill?

“It’s this reaction that people have,” he says. “People are desperate, people lose loved ones and get really frustrated about this increase in deaths, and they’re reaching for anything. One of the reactions is, let’s just keep penalizing people for using drugs and hope this is going to scare people.”

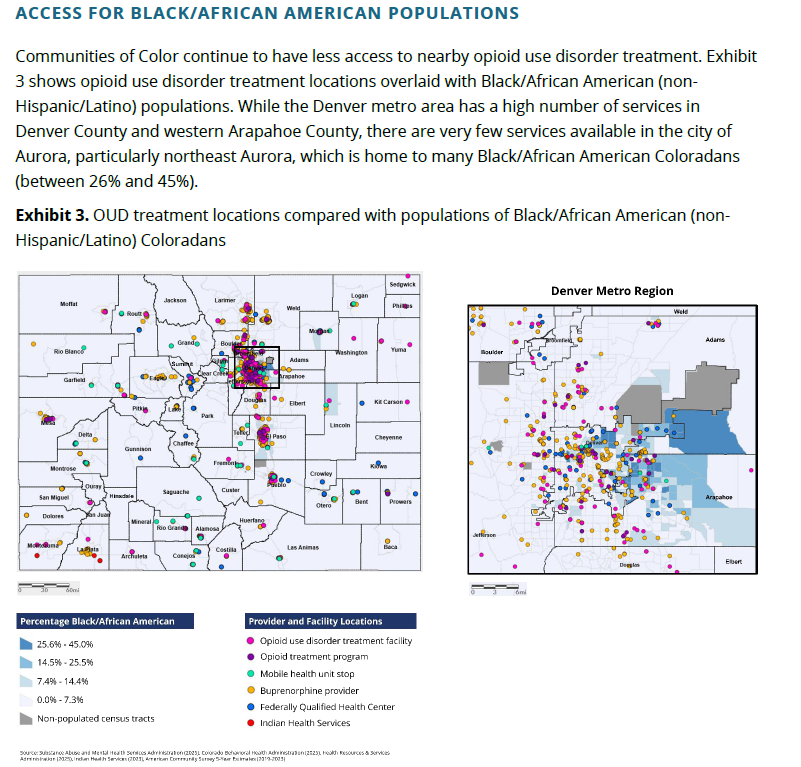

Medications like naloxone, which can reduce overdoses, and methadone and buprenorphine – FDA-approved medications that can help people stop or reduce their opioid use – are underused in the population most affected by overdose deaths, Esquibel argues. He points out that access to those medications has been sparse in Aurora on the east side of the Denver metro, which has the highest Black population. According to Esquibel, he and his organization have been “banding together with leaders of the Black community to look at ways to increase access to treatment, access to Naloxone (which can reverse overdoses), and access to recovery.”

Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention

Lisa Raville, executive director of the Harm Reduction Action Center, is a little more blunt in her criticism of HB 1326.

“We call it a trash piece of legislation,” she says of the law. “[The report is a] reminder that they will never treatment or incarcerate their way out of an unregulated drug supply – ever. There were mandatory treatment provisions [in the law], which is not evidence-based care.”

Jurecka, lead author of the reports, says he and his colleagues will continue to track the effects of the 2022 fentanyl laws as further data becomes available. Garnett, Pettersen and Cooke could not be reached for comment.