Bennito L. Kelty

Audio By Carbonatix

Denver Mayor Mike Johnston’s utilization of Flock Safety cameras, which use artificial intelligence to track and collect data by surveilling cars, drew a large and passionate crowd to a town hall hosted on Wednesday, October 22, with many people opposed to the technology.

Even Denver City councilmembers joined the criticism at the town hall, held by local advocacy groups that share a fear of government tracking.

“These are not our grandparents’ mass surveillance technology. This is so different,” Councilwoman Sarah Parady told an audience of hundreds. “If these were just cameras that were taking photos of all our plates and putting them in some database without the AI that has the capacity to read the plates, recognize the vehicles and fetch it all, that would still have horrified people in the 1960s.”

Johnston has been dealing with mounting opposition to the 111 Flock cameras that Denver has had installed at seventy spots throughout the city. The cameras were first installed in May 2024, but started facing more public heat as a contract extension with Flock Safety, an Atlanta-based company, came up this year amid aggressive immigration deportations across the country.

Fears surrounding Flock cameras involve potential federal agencies, such as Immigration and Customs Enforcement, using the technology to track down and persecute people. On Wednesday, opponents also cited a story where a Texas sheriff tracked down a woman seeking an abortion by using hundreds of the AI-enabled cameras.

City council voted down a two-year, $666,000 contract extension with Flock in May. However, Johnston signed a $498,500 contract extension for Flock in early August that, according to most of the speakers at the Wednesday town hall, was intentionally shy of a $500,000 contract review threshold that would have required council action. The contract pulls money from the city’s general fund despite a tight 2026 budget.

On Wednesday, Mayor Johnston announced that he had negotiated a new, more limited contract with Flock cameras. Under the agreement, data collected from Flock surveillance — including license plate numbers and AI-cataloged details like dents and colors — can only be accessed by the Denver Police Department. If that data is shared with federal agencies or other outside parties, Flock will face a $100,000 fine per instance and a potential contract nullification, according to the mayor’s office.

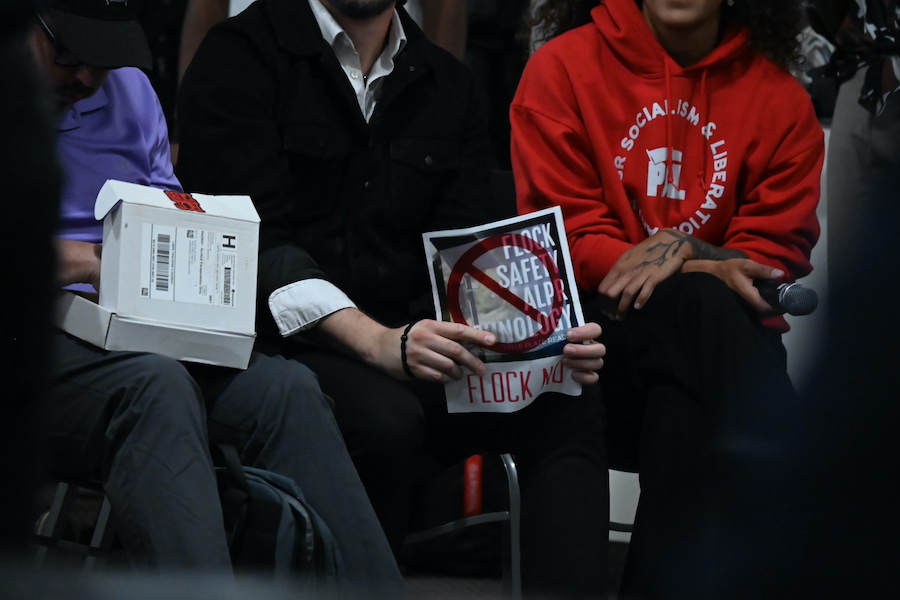

That wasn’t enough for opponents like the Denver Party for Socialism and Liberation, ACLU of Colorado, Newman McNulty law firm, Denver Task Force to Reimagine Policing and Public Safety and Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition, which had already scheduled the town hall when Johnston announced the renegotiation. Along with leaders of five Registered Neighborhood Organizations (RNOs) from Denver’s Whittier, East Colfax, Villa Park and other neighborhoods, activists demanded that the mayor shut off the Flock cameras completely, adding that they don’t trust him to keep their data safe at a time when they’re exceptionally afraid of the federal government.

Bennito L. Kelty

At least 500 people attended the town hall, according to the hosting venue in north Denver. The large turnout was driven in part by the presence of YouTuber Louis Rossmann, who has 2.5 million subscribers and makes tech videos about taxpayer-funded AI surveillance. One man there, Joshua Culver, told Westword he drove from Iowa to follow Rossmann’s coverage of the event and with hopes of curtailing the use of Flock cameras and similar technology in other states.

During the nearly two-hour event, city councilmembers, activists from the Denver PSL and ACLU as well as RNO leaders explained their fears of AI-powered surveillance and their anger with the mayor’s tactics. Tim Hoffman, Johnston’s director of policy, had the unenviable task at the town hall of defending the mayor’s commitment to Flock cameras.

Hoffman repeated that the new agreement’s terms restricted outside access to collected data as much as possible. He stressed that the Denver Police Department “as of now, is the only agency in the country that has access” to Denver’s Flock data. He also made the point several times that DPD can only look at resident data if their car is stolen or involved in a crime.

“Yes, there are pictures being taken at these 111 locations of the camera,” Hoffman said. “But they are not being searched by anybody unless your car is suspected of being either stolen or involved in another crime. So there is a difference between the mass surveillance where everyone is being watched all the time and the data being passively collected.”

According to the mayor’s office, Flock cameras have “helped Denver Police recover 39 firearms, make 352 arrests, recover more than 250 stolen vehicles and resulted in the capture of individuals suspected of sexual assault, murder, and fatal hit-and-runs” since 2024. Hoffman repeated those data points at the town hall, but several times throughout the night, Hoffman could barely finish a sentence as people kept interrupting him. Audience members yelled out “liar,” “recall” and “shame.” Some crowd members said the mayor was acting like a king, and one person even shouted “Luigi the mayor,” referring to Luigi Magione, the man who killed a healthcare CEO last December.

Councilwomen Parady and Serena Gutierrez-Gonzales, who both represent the city at-large, had to repeatedly intervene to calm down the crowd and ask them to let Hoffman speak. Along with Councilwoman Shontel Lewis, who represents north Denver, Parady and Gutierrez-Gonzalez were there to answer audience questions and voice their opposition to Flock cameras.

John McKinney, president of the East Colfax Neighborhood Association, called Johnston a “fucking pussy” for not debating Flock cameras in a public forum, a message that got uproarious applause and cheering. Lewis, in a nod to the No Kings protest on Saturday, October 18, said that Johnston signing contracts with Flock without City Council approval is “king shit.” Lewis and Johnston previously spoke about Flock cameras in a Central Park town hall together in September, and while they disagreed about keeping them, Lewis’s arguments were much more toned down last month than they were on Wednesday.

“It’s important for you all to identify the kings in the castle in the cities in which you all live,” Lewis said. “And the mayor is one of those.”

Bennito L. Kelty

Strong Council Opposition

Parady had the most to say in opposition to the cameras. She talked about how Denver’s Flock camera data was accessible to other jurisdictions nationwide until July, something the public wasn’t told.

According to the ACLU of Colorado, logs attained through a public records request showed Denver’s Flock cameras were “accessed” over 1,400 times by ICE, but Hoffman explained that activists were misunderstanding that number. He argued that nothing proves that those instances led to an arrest for a civil immigration violation, stressing that this happened when Denver was on a national network, which it left on Wednesday.

“The vast majority, if not all of those 1,400 searches, were another jurisdiction, almost always out of state, who were essentially doing a Google search of all Flock systems nationwide,” Hoffman explained. “There is no evidence to suggest that any of those 1,400 led to a positive hit in Denver of a license plate.”

However, the lack of transparency in how Denver data is stored speaks poorly of Flock, according to Parady.

“Flock put us on [the national network] without any permission and without telling us, and we decided this company is so trustworthy, we’re going to do a little handshake deal with them,” she argued. “I am not okay with it.”

Parady’s opposition was also driven by a fear of AI-powered surveillance. She’s “certain” Flock Safety sold the data of Denver drivers to companies that train similar AI surveillance tools, and she worries that “past repressive regimes didn’t have anything like this,” she said. According to Parady, Flock cameras have data on everyone who has ever driven in Denver during the past year and a half.

“We’re using this tool to train everybody else’s tools to track us…that’s the real value of our data,” she said. “I am legitimately, absolutely terrified by the state of AI surveillance.”

Bennito L. Kelty

Data giant Palantir has also come under fire in Denver because of its contracts with ICE; the company’s headquarters are located in Cherry Creek.

Gutierrez-Gonzales was upset that Johnston went around the council and a Flock task force they sent up in May, and then again to renegotiate the deal announced on Wednesday.

“I don’t want to shove something through. I don’t want to force people into something they don’t want to do,” she said. “The reality is that this technology is going to continue to exist, and it is upon us on city council and the mayor’s office to protect everybody in this city from that technology.”

West Denver Councilwoman Flor Alvidrez had a similar message in a statement she released on Wednesday, October 22, saying she was “tired of seeing major public safety decisions made behind the council’s back. Extending Flock again without a vote undermines democratic oversight and public trust.”

Councilman Kevin Flynn, who represents southwest Denver and is on the Flock camera task force, is the only councilmember to publicly support Johnston’s new contract, saying “I’ve been asking for strong guardrails around use of this technology, and this new structure provides them” in a Wednesday statement from the mayor’s office.

“The system has already proved its worth in solving crimes around the city,” Flynn said. “We can boost safety while ensuring the data is restricted.”

The RNOs represented at the town hall echoed disgruntled councilmembers. Kathy Sandoval, a member of the Villa Park Neighborhood Association, said that her RNO obtained a map of Flock cameras showing they are disproportionately located in Denver’s Hispanic west side neighborhoods.

“There is so much lack of transparency in this whole process,” she said. “The track record that you have does not build trust. This is an invasive surveillance practice.”