Frederick Police Department/YouTube

Audio By Carbonatix

You’ve got to admire Axon Enterprise, the weapons and technology firm based in Scottsdale, Arizona, for its skill in cornering a market. Axon started out in 1993 as AIR TASER (the name is an acronym for Thomas A. Swift’s Electric Rifle) before becoming TASER International, the company that made its non-lethal electroshock weapons ubiquitous in police departments around the globe. It soon expanded its offerings to include body cameras and in-car cameras for police officers, along with drones, license-plate scanners, and software solutions for evidence and records management.

Axon’s most controversial new offering, Draft One, made its Colorado debut in May 2024 at the Frederick Police Department in Weld County, one of the first agencies to adopt the technology; it’s now spreading through police departments across the state and around the country. Draft One uses OpenAI’s GPT-4o to take transcribed audio from Axon’s body cameras and auto-generate police report drafts for officers, who then review the draft, fill in some blanks, and check it for accuracy before pasting the final report (the AI draft is forever deleted) into the department’s records management system.

According to an Axon spokesperson, the AI training model was calibrated to remove creativity or embellishments that have cropped up in other AI uses. Legal and civil rights experts, however, are suspicious of using artificial intelligence in the criminal justice system, where AI hallucinations have already gotten attorneys in hot water, as when MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell’s lawyers filed a motion with nearly defective citations pulled from AI; they were subsequently fined.

Front Range law enforcement agencies that have adopted Draft One include Fort Collins and Colorado Springs, as well as the Arvada, Aurora, Boulder, Lakewood and Westminster police departments. The Denver Police Department has looked into the technology, but “at this point is not pursuing any adoption or purchase of the technology,” according to a DPD spokesperson.

Departments that use the technology praise its streamlining of the report-writing process, saying it frees up 30 to 40 percent of an officer’s time. As for errors, the software has an option that calls for AI to insert a nonsensical sentence that the officer must catch and delete before filing the report to prove it’s been read carefully – but not every department keeps this feature turned on. Arvada and Westminster police have disabled it, for example, but the Frederick and Wheat Ridge departments use the option.

Still, the concept is fairly dystopian. “Do you remember the vision of RoboCop from the ’80s and there’s this one cop with all the cyborg technology?” asks Dave Maass, director of investigations for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital civil liberties watchdog. “The entire concept of policing is now just Axon machinery with a little bit of police officer flesh in there. Axon is offering virtual reality training systems for police officers. When a police officer gets in the car, the car’s got inside and outside cameras from Axon. The officer himself is wearing an Axon body camera that’s recording the whole incident. His firearm is an Axon TASER. He’s got an Axon automated license-plate reader, maybe he’s got Axon drones. After the incident, Axon Evidence is managing all of the evidence, the Axon system is writing the police reports, the Axon system is keeping track of all of the cameras and their camera networks.”

Ian Farrell, an associate professor at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law, wonders what documents were used to train Axon’s AI narrative assistant. “The AI generates something that it thinks it wants you to have,” he says. “In a police report, that may be more likely to be inculpating than exculpating. If there are any sort of embedded problems in police reports that it’s being trained on, those will be reflected in the output of the AI.”

“We prioritize ongoing development of our products without the use of customer data whenever possible,” an Axon spokesperson responds, then acknowledges that there is a voluntary program through which agencies can share content with Axon to help develop new products, while declining to share specifics.

Potential pitfalls in this technological adoption by police agencies are easy to conjure. How does AI distinguish a suspect saying “yeah” in acknowledgement of what an officer’s saying versus admitting to an allegation? How does it identify an idiom like “That’s the bomb?” Can AI catch sarcasm in a statement like, “Yeah right, I killed him?”

Because the initial AI draft created by Draft One is not retained, who’s to blame if the police report contains a blatant error?

“At Frederick PD, draft reports generated by Draft One are thoroughly reviewed and edited by the reporting officer to ensure the accuracy of both the situation and the dialogue,” says Renae Lehr, director of communications and engagement for Frederick, the first department to use Draft One.

“There is no way that an officer can directly submit a Draft One report into our records management system,” says Aurora public information officer Matthew Longshore. “What typically happens is the officer copies the Draft One, pastes that into a Word document, makes the necessary changes, revisions, clarifications, updates, etc., and then transfers that report into our records management system.”

“Every report is still 100 percent the responsibility of each officer who authors it,” says Dionne Waugh, the public information officer for the Boulder Police Department. “Regardless of whether an officer uses Draft One when they write a report, they are responsible for the content within it.”

“Any nuances such as sarcasm, interpretation of statements, or contextual details are assessed and edited by the officer prior to submission,” says Sergeant Bob Younger of the Fort Collins Police Department.

AI in Action

The Arvada Police Department offered a chance to see Draft One in action.

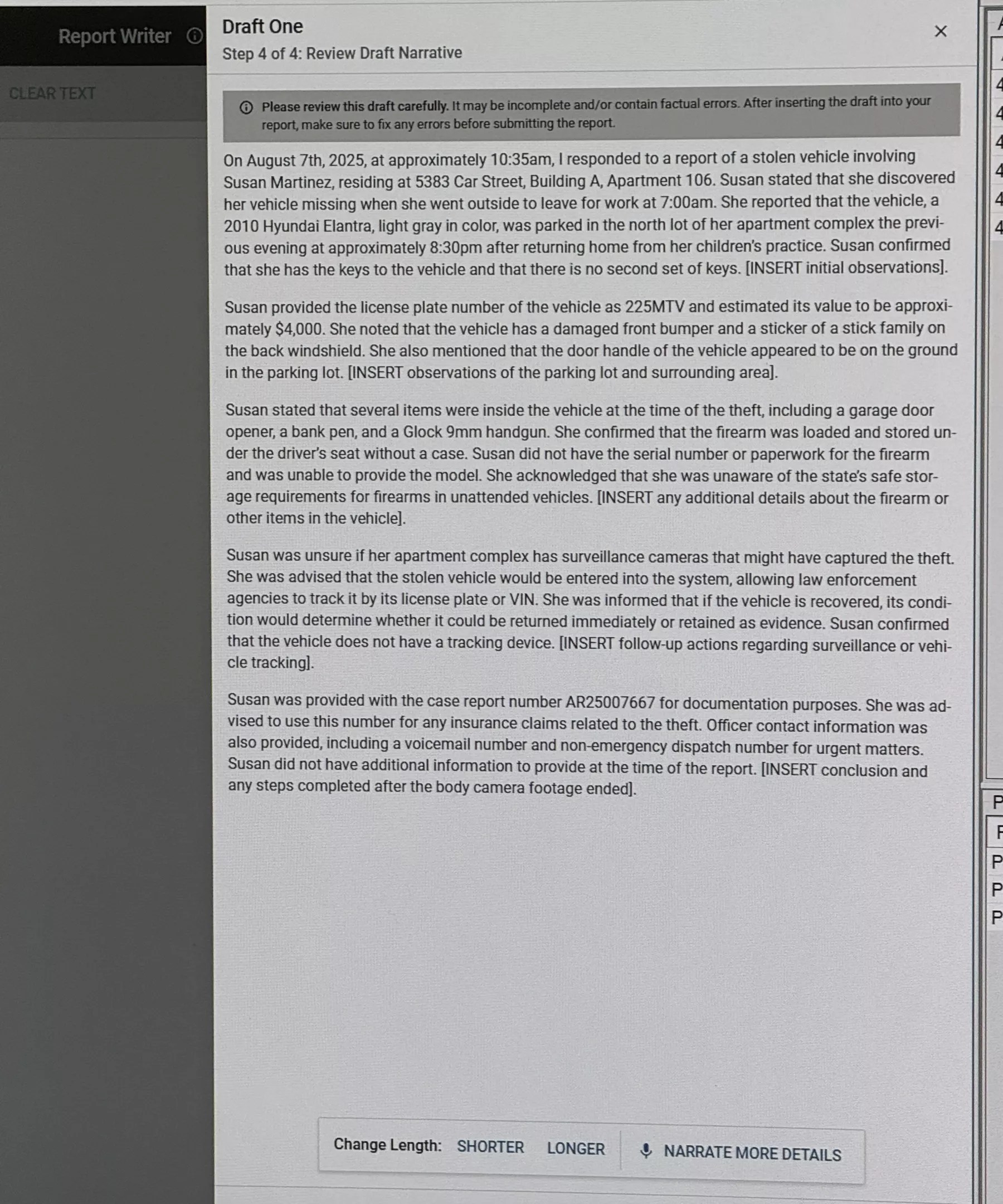

Officer Craig Smith provided a demonstration of the technology, with a department intern calling in to report a stolen vehicle – a common call for service, Smith said, requiring a basic police report. Smith’s interaction with the “victim” took seven and a half minutes. Within about five minutes of Smith switching off and docking his body camera, the Axon software kicked out a draft of the police report.

Each paragraph ended with a bracketed instruction, like “[INSERT observations of the parking lot and surrounding area].” The text cannot be copied out of the Notepad-like interface until those brackets are removed by the officer, Smith said. He had some immediate changes: the formatting of dates and the time, and the series of elements when describing a vehicle. Still, he had the report edited to his satisfaction within ten minutes.

Draft One’s initial draft of a police report for a staged demonstration of the technology.

Brendan Joel Kelley

Draft One wasn’t perfect – the “victim” had spelled out her fake name as M-A-R-T-I-N-E-S but AI put it down as “Martinez.” Also, she’d specified that she’d left a vape pen plugged into the stolen vehicle; Draft One wrote it was a “bank pen.” Smith caught the mistakes, though.

According to the Arvada Police Department, the final report remains the officer’s full responsibility. And Chase Amos, the PIO for the department, tells Westword that Draft One has increased report writing efficiency by 50 to 60 percent.

In some instances, Amos says, Draft One reports seem to err in favor of suspects. “If Craig is arresting someone and he says, ‘Eff you, I’m going to kill your whole family, go to hell, I hope you die,’ Draft One will say ‘So-and-so was upset that they were being arrested.'”

But some reviews of the technology have questioned its supposed efficiency – Draft One’s main selling point. After the Anchorage Police Department did a ninety-day trial last fall, it chose not to keep the technology. “We were hoping that it would be providing significant time savings for our officers, but we did not find that to be the case,” a deputy chief told municipal lawmakers.

A study published in a criminology journal last year determined much the same thing, announcing “Artificial Intelligence Does Not Improve Police Report Writing Speed.”

The Prosecuting Attorney’s Office in King County, Washington, which includes Seattle, issued a notice to law enforcement agencies in the region that it would not accept any police report narratives created with AI. Among its concerns about Axon’s process: “It does

not

keep a draft of what it produces or what the officer fixed/added. It alone decides what parts of the audio are unintelligible. It has ‘hallucinations’ (errors) both large and small. It does not track its rate of errors, or how many errors an officer fixed in prior drafts. While an officer is required to edit the narrative and assert under penalty of perjury that it is accurate, some of the errors are so small that they will be missed in review.”

The proverbial jury is still out as to whether Draft One should have a place in today’s criminal justice system. “My concerns are that we’re going to have freaking MechaHitler in the police report,” says Maass, referring to Elon Musk’s AI system Grok, which went full Nazi this summer, calling itself MechaHitler, praising Hitler and spewing anti-Semitic insults on X.com. “Ultimately, we just don’t know. This is totally untested technology that is really messing things up in the real world.”