Westword Photo Illustration

Audio By Carbonatix

One hundred years ago this spring, Denver elected Ben Stapleton as its mayor. Few voters knew that Stapleton was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. It was the start of a skillful march to power across Colorado that would soon lead to the election of a Klan governor, a Klan-dominated state legislature and two KKK-backed U.S. Senators. Most public officials declined to speak out against the group; one who did was Denver’s top prosecutor, a conservative Republican who viewed the Klan as a criminal conspiracy.

The following is an excerpt from GANGBUSTER: One Man’s Battle Against Crime, Corruption, and the Klan, a nonfiction account of the exploits of Philip Sidney Van Cise (1884-1969). Elected as Denver’s district attorney in 1920, Van Cise used electronic surveillance and other cutting-edge methods to expose a corrupt city administration and dismantle an organized-crime ring that had been thriving in Denver for years. His successful prosecution of crime boss Lou “The Fixer” Blonger and his crew of confidence men emboldened him to launch an undercover operation against an even greater threat: the Ku Klux Klan.

Originally a white supremacist group that emerged in the Deep South during Reconstruction, the KKK was revived in Georgia in 1915 as a secret fraternal organization and spread across the country after World War I, attracting millions of followers by capitalizing on white Protestant fears about immigrants, Blacks, Jews and Catholics. Under the leadership of physician John Galen Locke, the Colorado Klan grew rapidly, becoming one of the most powerful state chapters in the nation. Alternately courted and attacked by the Klan, Van Cise fought the KKK takeover and set in motion a series of criminal investigations, press exposés and scandals that would result in the collapse of the KKK’s influence in Colorado less than four years after the election of Stapleton.

Courtesy of the Van Cise family

In the spring of 1923, the political talk among Denver’s leading citizens tended to revolve around one consuming question: Who was going to run the city? The Blonger trial had exposed the stench of corruption permeating Mayor Dewey Bailey’s administration. A reckoning seemed to be at hand, an opportunity to clean house, to break with Denver’s tradition of phony reforms and pliable leaders and restore confidence in local government. But Bailey was forging ahead with plans to pursue a second term, and the mayoral election was only six weeks away, touching off a scramble to find a candidate who could beat him and his well-funded machine.

The obvious choice was the Fighting DA. Calls for Van Cise to declare his candidacy began even before the Blonger trial was over. A clip-out “membership application” appeared in newspapers, inviting readers to join the Van Cise for Mayor Club. On the evening of March 30, scarcely 48 hours after the jury returned its guilty verdict, Van Cise hosted a gathering of fifty friends and supporters, many of them prepared to get the campaign in motion as soon as he gave the word.

But Van Cise had other ideas. A cartoon on the front page of the next day’s Denver Post depicted the DA being offered a ticket to the mayor’s office on a golden platter; the caption read, IT DIDN’T TEMPT HIM VERY LONG. Van Cise released a statement declaring that not only was he not running for mayor, “I will not be a candidate to succeed myself in my present office.” He had unfinished business as district attorney and a four-year “contract” with the voters that he intended to honor. But after that he was done. He wouldn’t rule out a run for higher office someday, but the mayor’s job wasn’t for him.

Unlike the district attorney race, Denver’s mayoral elections were nonpartisan; a person needed only a hundred signatures on a petition to run for mayor, and no candidate could rely on party affiliation to carry the day. Calling the Bailey administration “a disgrace to American government,” Van Cise urged the five challengers already in contention to “select one of their number to make the race and definitely concentrate the opposition to Bailey into one real army. If all they want is cheap notoriety, they will all stay in the race and go down to an inglorious defeat.”

Van Cise threw his support to Mark Skinner, a Democrat and former state senator who was being touted as the “fusion candidate,” capable of uniting business, labor and reform interests. But Skinner’s campaign lasted only two weeks before he was forced to withdraw. The city charter required that a mayoral candidate must have lived and paid taxes in Denver for five years; Skinner, formerly of Colorado Springs, had been an official resident of the Mile High City for only four years. With the petition deadline for new candidates only hours away, Skinner’s backers hustled to find a suitable replacement.

The new fusion candidate was George Carlson, a man after Van Cise’s own heart. He had been a district attorney in Fort Collins, known for cracking down on gambling and graft. He had also been Colorado’s first dry governor, overseeing the implementation of the state’s early prohibition law in 1915-16. With less than three weeks to go before the election, Van Cise went on the stump for Carlson, praising him as a fighter, a doer of deeds, “a he-man who knows how to enforce the law.”

But some elements of the anti-Bailey forces did not warm to Carlson, a Republican known for his hostility to the labor movement. Progressives, union leaders and Governor William Sweet, a Democrat, drifted toward the other major contender in the race, Benjamin Franklin Stapleton. Fifty-three years old, bland and pragmatic, Stapleton was nobody’s idea of a he-man, but he was well-connected in Denver political circles. He had allies in the Democratic machine as well as among the bankers on Seventeenth Street and the leaders of the city’s ethnic neighborhoods. Born in Kentucky, he’d moved to Denver as a young man and served in the Spanish-American War. He never quite got his law practice off the ground, but he’d held various city jobs under Mayor Robert “Bunco Bob” Speer, including justice of the peace and police magistrate. In 1915 he’d been appointed as Denver postmaster, a much-coveted federal sinecure. In the mayoral campaign, he stressed his knowledge of police operations and city government in general. He promised to put together a businesslike, efficient, nonpartisan administration.

“He was a nonentity,” recalled Charles Ginsberg, a politically active Denver attorney who initially supported Stapleton, in an oral history given many years later. “He was a police judge that nobody knew or cared about. He was just a name. There was nothing against him and nothing for him.”

“Any attempt to stir up racial or religious prejudices or religious intolerance is contrary to our constitution and therefore un-American.”

Yet Ginsberg and a few other reformers feared that Stapleton wasn’t quite as nonpartisan as he claimed to be. He was a joiner and a Mason, and there was talk that in his youth he’d joined the American Protective Association, an anti-Catholic secret society, and that he might be tied to the Ku Klux Klan. Crime and corruption were undeniably the top issues in the election, but the growing influence of the Klan across the state was also a concern – so much so that Ginsberg and Phil Hornbein, another prominent attorney, urged Stapleton to issue a statement denouncing racial bigotry. The candidate complied. Although the statement didn’t mention the Klan, everybody knew what group he was talking about.

“True Americanism needs no mask or disguise,” Stapleton declared. “Any attempt to stir up racial or religious prejudices or religious intolerance is contrary to our constitution and therefore un-American.”

The race was a close one. The city had a ranked-choice voting system that allowed voters to select their first, second and third choices among the eight mayoral candidates on the ballot. Bailey drew the most first-choice votes, but Stapleton fared better in total numbers, pulling ahead of Bailey by 6,000 votes out of nearly 70,000 cast. Carlson finished a distant third.

Among contemporary observers, Stapleton’s narrow victory was largely credited to his ties to the Democratic machine, but other forces were at work, too. The deciding factor may have been the grassroots, get-out-the-vote campaigning on his behalf by an organization the candidate never acknowledged. The concerns about what Stapleton really stood for were well-founded. He was a longtime friend of John Galen Locke, the eccentric Grand Dragon of Colorado’s Ku Klux Klan, and Stapleton had been issued Klan membership No. 1128 – a number low enough to suggest that his KKK initiation had occurred long before he declared his candidacy. Nor was he the only closeted Klansman in the mayor’s race. Although Van Cise didn’t know it, the man he’d supported at the outset, Mark Skinner, held membership No. 1108, his name entered just a page ahead of Stapleton’s in the official Klan roster.

Formally, the Colorado Klan hadn’t endorsed any candidate, recognizing that its public support could be a liability for the office seeker. It was still operating from the shadows. But that was about to change. Days after the election, a single Klansman in robe and hood posed on the steps of Denver’s City Hall, one arm raised in salute. The photo ran in the KKK’s national magazine, The Imperial Night-Hawk, and there was no mistaking its meaning. The Klan had arrived at the seat of Denver government, and it was settling in nicely.

Ben Stapleton was elected mayor of Denver with the Klan’s help.

City of Denver

Stapleton’s election as mayor came just over two years after the Klan had established its first foothold in the state. In 1921 the national leader, Imperial Wizard Joseph Simmons, came to Denver at the invitation of Leo Kennedy, a former American Protective Association leader, to meet with like-minded businessmen who were interested in starting a local klavern. Simmons gave his pitch in a private gathering at the Brown Palace and ended up enrolling several enthusiasts on the spot.

By most measures, Colorado was an unlikely venue for the racist, anti-immigrant agenda Simmons was peddling. The state had no deep-rooted history of racial violence – nothing that approached the systematic oppression in the South, certainly, or the 1921 race massacre in Tulsa, which left hundreds dead and leveled an entire Black neighborhood. Blacks represented less than two percent of Colorado’s population, and they tended to be better-educated and have a higher degree of home ownership than Blacks in the Northeast or the South. Denver’s population was overwhelmingly white and born in America, yet fully half of the residents had at least one parent who was born in another country. Roughly one out of seven Denverites was Catholic, and thriving Catholic parishes could be found across the state.

But Colorado proved to be surprisingly fertile ground for the Klan. The Centennial State didn’t have the South’s legacy of slavery, but its own brief on race relations was hardly bloodless, from the 1864 slaughter of hundreds of Arapaho and Cheyenne women and children, an atrocity that became known as the Sand Creek Massacre, to an 1880 anti-Chinese riot in Denver, to the scores of people executed without benefit of trial by frontier lynch mobs. (The “court of Judge Lynch” remained open decades after the frontier closed; one of the most repugnant murders occurred in 1905, when Preston Porter Jr., a fifteen-year-old Black railroad worker accused of raping and killing a twelve-year-old white girl, was chained to an iron stake outside the eastern plains town of Limon and burned alive in front of a crowd of 300, including numerous newspaper reporters.) Denver’s white citizens may have considered themselves less prejudiced than their benighted relatives in the Jim Crow South, but a color line ran through the town, segregating housing and schools, theaters and swimming pools, restaurants and parks. Discrimination against Catholics and Jews was less pervasive but still significant, keeping them clustered in ethnic neighborhoods and almost completely absent from the ranks of judges, councilmen, or other positions of authority.

The fault lines of racism and religious bigotry were already there, waiting to be exploited. Yet it’s doubtful that the Colorado Klan would have amounted to much without the canny and opportunistic leadership of its chief. Over the course of three years, Locke transformed the Colorado Realm into one of the most politically powerful Klan organizations in the country, second only to Indiana in per capita support – and second to none in the degree to which it controlled state government.

John Galen Locke helped engineer the Klan takeover of local and state government.

Denver Post Collection/History Colorado/Accession No 86.296.2998

Accounts differ as to whether Locke attended that first meeting with Simmons. He was an early convert, in any case, and firmly in charge of the Denver klavern by the time he appeared before a grand jury in 1922 and denied being a Klansman. On May 14, 1923, he was appointed Grand Dragon of the Colorado Realm. Pompous, melodramatic, a showman-cum-dealmaker in the tradition of Phineas T. Barnum and Niccolò Macchiavelli, he was the perfect choice to head an organization that relied on theatrics, lies, and misdirection to further its aims.

Born in 1871 in New York City, Locke was the oldest son of a surgeon, Charles Earl Locke, who’d fought for the Union during the Civil War. In 1888 Charles Locke moved his family and his practice to Denver. Both father and son enlisted in the Colorado Volunteers during the Spanish-American War; Charles was wounded in battle in Manila, while his son never saw combat.

J.G. Locke studied medicine at various schools and finally received his medical degree in 1904. He chose to pursue homeopathy, at a time when so-called “natural” remedies were falling out of favor with the medical establishment. For the rest of his career, he remained an outsider in Denver professional circles – scorned by the local medical society as a borderline quack, adored with almost cultlike fervor by his patients for his homemade potions, compassion, and modest fees.

His rogue medical practice was probably the least exotic thing about Locke. Short, round, tipping the scale at 250 pounds, he had the physique of a bullfrog but a shrill squawk for a voice, supposedly the result of damage to his larynx from a brawl in his youth. His fans considered him a mesmerizing orator just the same. He had a fondness for well-tailored suits that hid his rotundity, for diamond jewelry and military regalia. He rode around town in a red Pierce-Arrow that had a family coat of arms emblazoned on its doors, like a generalissimo’s staff car. He loved to hunt, toted a .44 most of the time, and was reputed to be a champion knife thrower.

Locke had an office and surgery downtown on Glenarm Place, next door to the Denver Athletic Club, that also served as his residence and Klan headquarters. The place was like something out of a Lon Chaney movie, decorated with displays of armor, antique weapons and animal heads. Locke kept more than two dozen guns and several crates of ammunition in a vault in the basement and more firearms in a chest upstairs. Behind a hidden door was a throne room where, flanked by hooded flunkies and his dogs, a Dalmatian and two Great Danes, he met with Klan supplicants. One reporter who visited him had the impression that Locke “was living in the Middle Ages, that he was sort of a romantic man.”

A 1918 biographical sketch describes Locke as an Elk, an Episcopalian and “a prominent figure in Masonic circles.” Yet whether he ever believed in the KKK’s teachings remains an open question. His personal conduct was greatly at odds with the Klan’s anti-Catholic stance. No matter how volubly he might denounce Catholics at meetings or dress down subordinates for fraternizing with them, he had many Italian-Americans as patients, and he employed two Catholic sisters as secretaries and nursing assistants. After his death, stories would surface that he had dissuaded his more rabid followers from acts of violence against Catholic targets, including a scheme to blow up the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, the Denver diocese’s lavish French Gothic mother church in the heart of the city. Locke told the plotters that the diocese would simply collect insurance on the loss and build an even grander temple.

In his writings, Locke described Jews, Catholics, and Blacks – or, as he put it, “the exploiter, the moral tyrant and the usurper,” respectively – as the enemies of white civilization. Yet he also urged a certain degree of moderation in battling those enemies. He had seen what had happened in other states, such as Texas and California, where Klan vigilante actions quickly spiraled out of control, leading to raids and indictments and pariah status for the organization. Locke was interested in broadening the Colorado Klan’s reach and its power, not marginalizing it by catering to its most militant true believers.

To accomplish this, Locke focused on recruitment and feel-good media events. Klansmen teased the press with bits of theater, showing up unexpectedly in their finest robes at funerals or church services and offering a donation. When a prominent Denver restaurateur died, a plane dropped white carnations on the funeral procession, each one affixed to a red ribbon bearing the words KU KLUX KLAN. When famed evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson came to Denver on a lecture tour, the Klan “kidnapped” her and pledged its protection. When acts of intimidation came to light, such as the threatening letters sent to a Capitol Hill janitor and NAACP leader George Gross, they were disavowed – blamed on stolen stationery or some other handy excuse. These were all preliminaries, signs that the Klan was biding its time and awaiting its moment.

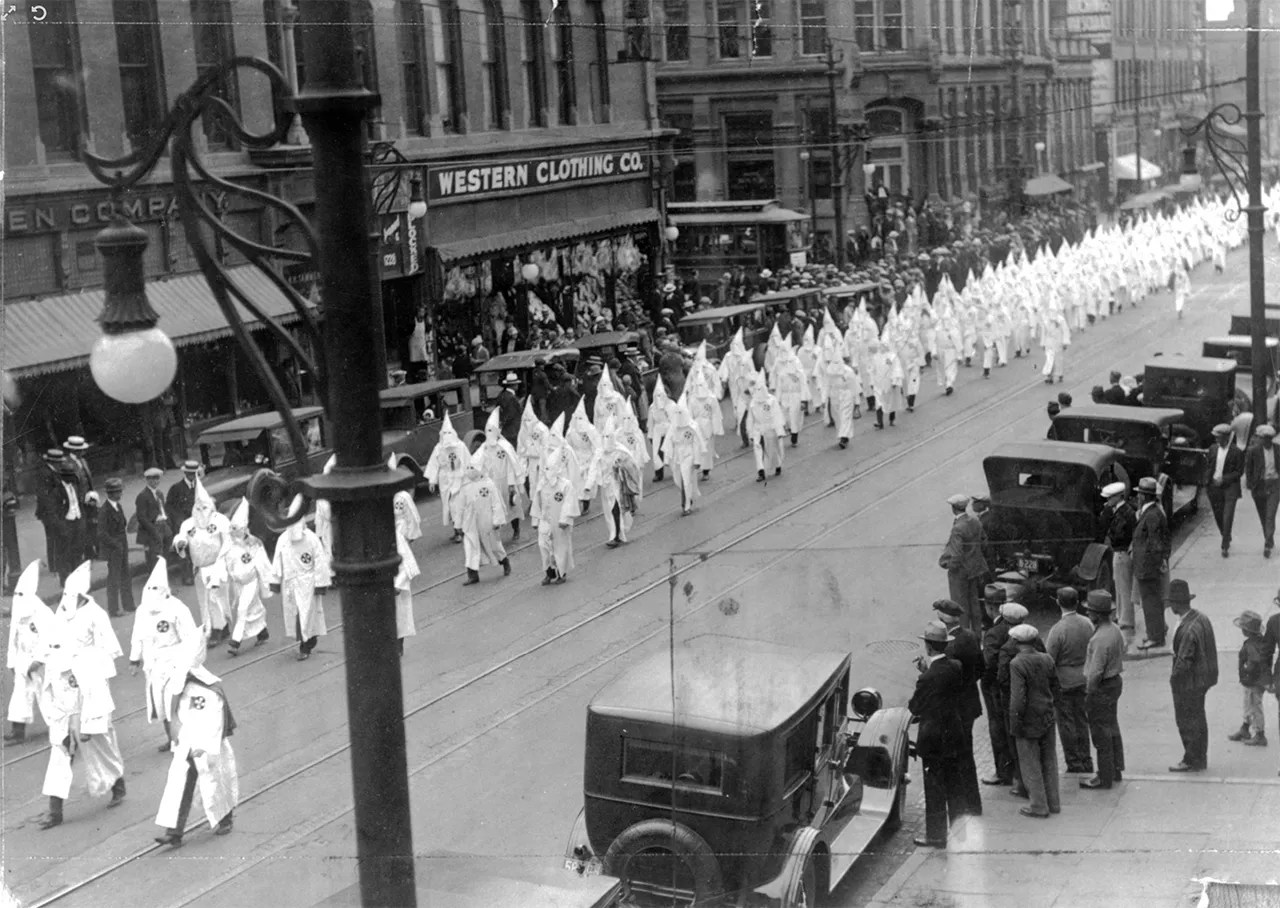

Klansmen paraded through downtown Denver on May 31, 1926.

Denver Public Library Special Collections/Call Number X-21543

Six weeks after the election of Mayor Stapleton, handbills appeared around town announcing an upcoming lecture at the City Auditorium that would explain what the Ku Klux Klan was all about. The speaker, George C. Minor, was a paid apologist for the Klan, one of several Protestant ministers who went around the country defending the organization. The news caused an uproar. Not only had the new administration seen fit to rent out a city facility to the Klan, but placards announcing the event had been affixed to the doors of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, as well as to the doors of several other churches and synagogues, a clear provocation.

The day before the lecture, Stapleton met with one delegation of concerned citizens after another, demanding that he cancel the event. They included Catholic and Jewish leaders, representatives of the NAACP, and attorney Phil Hornbein, who reminded Stapleton of his campaign pledge renouncing bigotry and secret organizations. Governor Sweet sent a telegram: “No possible good and much harm will result from this meeting.” Stapleton waffled but ultimately insisted that the show must go on. The Klan was entitled to present its views, he said, as long as it didn’t attack any other race or creed.

The free lecture was slated to start at 8:30 p.m. on June 27. The auditorium quickly filled with an estimated 4,000 people, a mix of Kluxers, anti-Kluxers, and the curious. After a brief organ recital, Minor took the stage. He began by daring the crowd to send him packing: “If there is a single man in the audience who does not wish to hear what I have to say, let him rise to his feet, and I will withdraw.”

Several people stood up: a Black minister, a little girl, two Catholic priests from the cathedral. The priests had been chaplains during the war and were dressed in their Army uniforms. One of them, Father Francis Walsh, began to explain that he objected to the “invitation” he’d received, plastered on his church door. Applause broke out; others jeered and hissed.

Minor tried to quiet down the hecklers. Rice Means, Stapleton’s newly appointed manager of safety, announced that the meeting was over and ordered the audience to disperse. Amid grumblings and boos, the place quickly emptied. The Invisible Empire had tried to emerge from the shadows, but the moment wasn’t right yet; the best the group could hope for was to be seen as free-speech martyrs, muzzled by intolerant papists. But the wheel was about to turn. A few months later it would be the other side struggling to make itself heard, drowned out by a mob of Klansmen, under the direction of Grand Dragon Locke.

A poster for a Ku Klux Klan picnic at Lakeside.

Courtesy Van Cise Family

The flap at the auditorium did not go unnoticed at the district attorney’s office. The Klan was part of the unfinished business Van Cise was determined to clear away in his last eighteen months in office. He could see more troub le looming, now that Stapleton had revealed his Klan sympathies. Who knew how many cops, city officials, judges and state legislators were secretly Klansmen, too?

In his darker moments, Van Cise wondered if he had cleared out a rat’s nest at City Hall, only to see it replaced with something much worse. He talked to his deputy DA, Ken Robinson, about ways of investigating the Klan, or at least getting a handle on the identities of its leaders. The district attorney soon had five undercover operatives – a mix of volunteers and trained investigators, none of them known to each other – keeping tabs on Klan meetings. They staked out meeting halls and wrote down license plates, tried to infiltrate the meetings when possible. It was not all that different from shadowing Blonger and his friends – except that the number of persons of interest seemed to double every few weeks.

The Klan was spreading faster than a flu bug. Membership surged so rapidly in 1924 that the organization was in a perpetual hunt for larger meeting spaces. They had started out at a mortuary operated by one of their members, then relocated to a series of fraternal meeting halls downtown, each of them a short walk from Locke’s office. Then, as summer approached, they began to gather al fresco on top of Ruby Hill, a popular sledding area in southwest Denver, and South Table Mountain outside of Golden, a mesa at the edge of the foothills that offered an expansive view of downtown Denver. Locals called it Castle Mountain because of a blockish butte at the mesa’s northwest end.

A Ku Klux Klan gathering on South Table Mountain in Golden.

Denver Public Library Special Collections, Call Number X-21546

The downtown meetings had typically drawn a few hundred people. Monday nights on Castle Mountain were attended by as many as 8,000 people, their cars clogging West Colfax between Denver and Golden and jamming the exit road to the mesa for hours. Just a few months earlier, the Klan had been content to boast that it was “10,000 strong in Denver.” Now it claimed to have 50,000 members across Colorado, half of them in Denver. Those figures were inflated, but thousands of Kluxers on a plateau every week called for further investigation.

The Klan attempted to impose hush-hush security at its meetings, posting guards at the entrance, demanding membership cards or secret handshakes. When a reporter from the Denver Express was spotted staking out the Knights of Pythias Hall, studying Klansmen as they emerged, a Denver police officer was dispatched to run him off. But the Klan was outgrowing its anonymity. A special ceremony on May 13, 1924, marking the first anniversary of the charter granted to the Colorado Realm, featured remarks by Locke, Denver police chief William Candlish, city attorney Rice Means, prominent restaurateur Gano Senter, Denver District Judge Clarence Morley and several others, all identified in the program by name and some by title as well, including the Exalted Cyclops, the Grand Kludd, the Grand Klokard and the “Klaliff-elect Klan No. 1,” who happened to be Morley. When put on the spot in public forums, Means and Morley still denied being Klansmen, while Mayor Stapleton avoided answering questions about the Klan altogether. Yet here they were – in the official program, on the speakers’ platform, shuffling to and from Locke’s office, exhorting the multitudes from the mountaintop. The Klan wasn’t hiding in the shadows anymore.

The gatherings on Castle Mountain were grand spectacles. A Klan marching band played patriotic tunes and religious ballads. Preachers gave hellfire speeches while crosses blazed. An honor guard on horseback fired guns into the air. The white-robed throngs, which skewed young and boisterous, whistled and cheered and sang along. His squeaky voice amplified electronically, Locke played ringmaster, introducing one speaker after another, cracking jokes, fulsomely praising generous donors and berating the Klan’s enemies, updating his knights on the Empire’s relentless march to power. The Grand Dragon was an emotional, effective speaker, but one of Van Cise’s spies, Robert Maiden, thought the crowd reaction was less spontaneous than it seemed, right down to the prolonged outbursts of applause that appeared to originate somewhere near the platform and surge through the crowd like an electric current. Locke always seemed to be on the verge of a startling announcement, hinting about some looming, game-changing development that never came to fruition but sent the faithful into a frenzy anyway.

From what Maiden could see, it was just rabble-rousing, plain and simple.

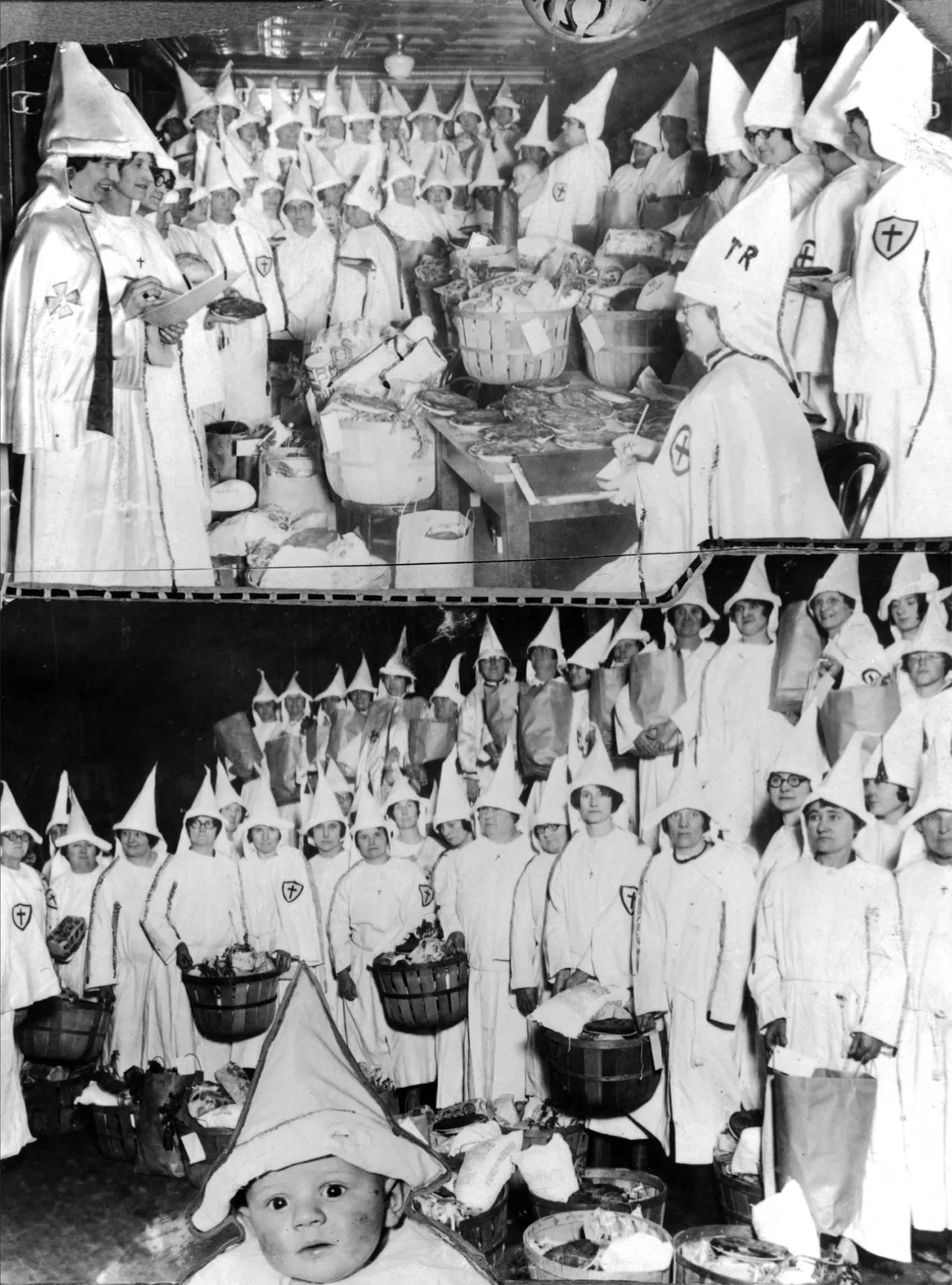

Klan mothers gather to educate the next generation.

Special Collections/Call #X-21540/Denver Public Library

The Klan came into its own that August, stunning the state’s political establishment with its grassroots organizing, its coordination, its unexpected numbers. At the Republican county assembly held at the city auditorium, representatives from neighborhood caucuses gathered to select delegates to the state convention and designate primary candidates. Roughly two-thirds of the assembled representatives were Klansmen, recognizable to each other by the white carnations they wore in their lapels. Klan police officers stationed at the doors tried to bar reporters and non-delegates, including several veteran party leaders. Locke directed the proceedings from the mayor’s box while Rice Means acted as floor leader. They effortlessly pushed through an all-Klan ticket of candidates, led by Morley for governor and Means for U.S. Senator, backed by a state delegation dominated by Klansmen. To cap it all off, Means then obtained overwhelming approval of his hand-picked list of delegates to the state convention without revealing who any of them were; most of those present had no idea who would be representing them at the convention.

Van Cise made several attempts to protest the hijacking of his party. “If we don’t get fair play, it’s going to split the party wide open,” he said.

He was hissed and shouted down.

A week after that, nearly 80,000 Denverites voted in the mayoral recall election, the largest turnout in the city’s history. The recall had been spurred by protests over Stapleton’s pro-Klan appointments, but Stapleton easily trounced his challenger, Dewey Bailey, by 31,000 votes, five times the margin of Bailey’s defeat in the mayoral election of 1923. The incumbent had carried every district in the city; Bailey’s only show of strength was in the Jewish neighborhoods on the westside. Stapleton released a terse statement saying that he felt “inspired” that the citizens of Denver had twice shown their confidence in him. Locke gave his first substantial interview to the Denver Post, gloating over the returns and leaving no doubt about the mayor’s true affiliations: “The Klan had charge of the campaign and election of Mayor Stapleton, and is entitled to credit for his overwhelming victory.”

The Grand Dragon likened his humming machine to the crackerjack efficiency and discipline of the U.S. Army. He spoke disdainfully of the district attorney, who had leaked spy reports to the Denver Express right before the recall election in a last-ditch effort to expose Stapleton’s kowtowing to the Klan. It hadn’t made any difference.

“We know – that is, I know – that today Phil Van Cise is trying to organize a committee of one hundred prominent or near-prominent men to fight the Klan in the coming campaign,” Locke told the reporter. “I know the name of each man who is taken into Phil’s organization. I know he peddled the Klan stuff to a newspaper, and I know he is very foolish to hate the Klan…I’d just like Van Cise to know that we know what he is doing.”

Locke was well-informed. After watching the Klan steamroll the opposition at the county assembly, Van Cise was scrambling to organize an alternative slate of Republican candidates before the primary election. He had enlisted a hundred business leaders and attorneys to sponsor the effort and was hastily recruiting candidates. Post reporter Forbes Parkhill, who was one of those persuaded to run for a seat in the state legislature, dubbed it the Visible Government ticket – a slate of public-minded citizens whose intentions and affiliations were clearly known, unlike the clandestine candidates of the Invisible Empire.

Van Cise organized a strategy meeting with his backers one evening at the westside courthouse. He invited fifty people to attend. Fearful that some might be scared off if their names were disclosed too soon, he avoided any public announcement of th e meeting. But Locke’s spy network was at least as good, if not better, than the one Van Cise had keeping tabs on the Grand Dragon. The night of the meeting, approximately 300 Klansmen gathered on the lawn outside the courthouse. They formed a line on both sides of the sidewalk. They called out the names of the arriving guests and discouraged several from entering the building. A hearty two dozen of Van Cise’s supporters ignored the taunts and attended the meeting. The group adjourned around ten, after deciding that the Visible Government ticket would hold several public rallies in the days leading up to the primary, including a major presentation at the City Auditorium.

Van Cise emerged from the courthouse around midnight. A scatter of Kluxers still lingered on the lawn, evidently waiting for him. His path to his car took him through a gauntlet of them. They bumped and shoved him, cursed him, swatted at him. That they didn’t do more was probably because of the brightly lit fire station next door. The fire department had not fallen to the Klan as completely as the police, and that night the station was staffed by Catholics and other anti-Klan employees.

Van Cise made it to his Ford. The Klansmen piled into their cars, waited for him to pull away, then followed. Van Cise felt like a grand marshal leading a parade. Instead of driving home, through the relatively empty streets of Capitol Hill, he headed downtown, the Kluxers in hot pursuit.

He had not gone far when he saw a water truck ahead, lumbering toward a hydrant. He slammed on the accelerator and squeezed into the shrinking space between the truck and the curb, then whipped around a corner. Behind him, he heard a crash and screams. Two cars remained on his tail. He took several sharp turns, pulled over on a deserted street, and proceeded on foot, creeping through alleys and hopping fences until he was home.

The next morning he phoned Locke.

“I am carrying a .45,” he said, “and I’ve run from your gang for the last time. When I shoot, I shoot to kill.”

He carried the pistol in a shoulder holster for months. A year or so later, he had a confidential conversation with a Klansman who claimed to have been one of his pack of pursuers that night. The man said that the group had planned to kidnap him and castrate him, but the presence of the Catholic firemen had made them hesitate. They figured they would have better luck catching up with him on the streets. Then the water truck got in the way, he said, “and your damned Ford was too fast.”

Alan Prendergast

From GANGBUSTER, by Alan Prendergast, reprinted with permission from Kensington Books. Copyright 2023.

At 6 p.m. on Friday, March 31, Tattered Cover will present author Alan Prendergast discussing GANGBUSTER: One Man’s Battle Against Crime, Corruption, and the Klan with Westword editor Patricia Calhoun at the store at 2526 East Colfax Avenue. Admission is free; learn more at tatteredcover.com.