Courtesy of Clayton Early Learning

Audio By Carbonatix

Parks and open-space advocates – including former Denver mayor Wellington Webb – were dismayed to learn that the now-shuttered Park Hill Golf Club will be sold to developers. The current owner is set to close a deal with Westside Investment Partners on July 11.

Neither side has announced particular development plans. The deal is wrapped up in a mess of pending litigation between the city and golf club operator Arcis Golf, and the land is currently subject to a conservation easement agreed to in 1997 that prohibits development. Still, advocates fear that the move could turn 155 acres of rolling green grass into housing complexes, office buildings and retail space.

The land that makes up Park Hill Golf Club is part of the George W. Clayton Trust, which is managed by Clayton Early Learning – a nonprofit that isn’t in the business of golf, open space or real estate, but serves low-income children and is a well-regarded preschool and educational research institute. And it’s on the hunt for more funds.

According to a statement sent to Westword by Charlotte Brantley, outgoing president and CEO of Clayton Early Learning, the 501(c)(3) “was and is in a very strong financial position.” Nonetheless, Clayton abruptly closed its second Educare Denver Center in June 2017 for financial reasons. Brantley says that Clayton Early Learning needs to sell the golf course in order to maximize its assets; it had been receiving just $700,000 annually in rental income for the golf course land.

“While the sale of the property will result in a substantial increase in the size of our assets, we first must use the proceeds to replace the $700,000 per year we were receiving in rental income for the property. … If only to keep up with inflation, our investment related to this asset of the Trust needs to generate approximately $1,000,000 annually,” according to Brantley.

Local open-space advocate and retired lawyer Woody Garnsey doesn’t buy that Clayton really needs to or should sell to developers. “When Clayton needed money in 1997,” he says, “they were very willing and interested in receiving $2,000,000 in exchange for relinquishing development rights forever.” (That easement is technically permanent, although the city can decide to lift it.) “Now, in an act of sellers’ remorse, they want to undo that entire deal.”

The fascinating history of the sticky situation in which Clayton Early Learning now finds itself goes back to 1899, when a wealthy Denver businessman and civic leader named George W. Clayton was found dead at his desk. To his family’s surprise, he left the vast majority of his approximately $2 million estate (over $40 million in today’s dollars) to the City of Denver. According to an information sheet written for the National Register of Historic Places, the trust was “to be devoted solely and exclusively to the founding, establishing, and forever maintaining a permanent college…[for] poor white male orphan children.”

Builders lay the foundation of Clayton College.

Courtesy of Clayton Early Learning

Clayton’s wife and son had already passed away, but one of his surviving brothers, a legal heir, was shocked to find that he wouldn’t get his due chunk of the estate. Thomas Clayton sued the will’s executors for $400,000, arguing that “the education of orphans was not a recognized public charity in Colorado.” (Notably, Mary Lathrop, one of the first women elected to the American Bar Association, wrote the briefs for the defense of the will. The suit was eventually settled in favor of the Clayton estate, a novel and widely lauded victory for both white male orphans and female attorneys. The victory was somewhat stifled for Lathrop, however, since she never recovered the legal fees she was owed.)

The city, meanwhile, set to work executing George Clayton’s will, and in 1911 finished construction of a school campus set on a twenty-acre tract of land at 32nd Avenue (now Martin Luther King Boulevard) and Colorado Boulevard. A collection of stone and brick buildings with red roofing in the Renaissance Revival style, it was an upscale orphanage for its time. Denver Municipal Facts wrote that the campus was a “marvel of beauty” that was “well worth a visit.”

Clayton College for Boys officially began admitting orphan boys in 1911 and quickly increased enrollment until it leveled out at about sixty boys each year. As they are with Clayton Early College’s extensive operations today, costs were comparatively high. Clayton College aimed to provide more than the standard orphanage; George Clayton had written that the boys “shall be instructed in such various branches of sound education as will tend to make them useful citizens and honorable members of society.” Of course, Clayton had also established rather selective criteria for who got to receive that instruction: white males of “reputable parentage” who were born in Colorado, in need of help, and whose fathers were deceased.

Clayton College’s campus opened its doors in 1911 as a home and school for “poor white male orphan children.

Courtesy of Clayton Early Learning

Clayton College served approximately 600 boys between 1911 and 1957, at which point a study by the Child Welfare League of America found that the College “continued to operate in a way typical of the 1890s and not in accordance to modern good practice in children’s institutions.” In 1969, courts liberalized some of the restrictions of Clayton’s will, opening the orphanage to children of any race and gender whose parents were unable to care adequately for them for a wider variety of reasons. Eventually, the school no longer saw a need for the residential component of its services, and shifted its focus to researching early education statewide. It also established an advocacy and policy program.

Clayton Early Learning still fulfills an amended version of George Clayton’s mission to educate the underprivileged, serving 590 children from birth to three years old last year, nearly all of whom qualified for Head Start funding. According to Clayton Early Learning, 57 percent of children who attend its Educare Denver School live in single-parent households, 35 percent speak Spanish as their first language, and more than 95 percent qualify for free and reduced lunch.

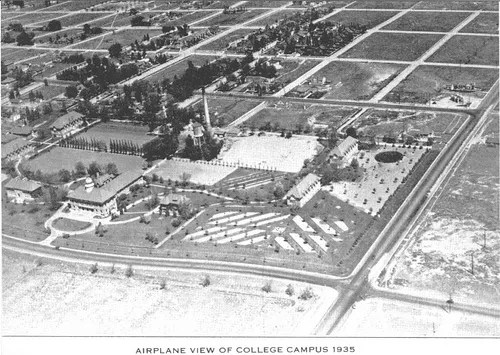

Originally a dairy farm, Park Hill Golf Club opened in 1932.

Courtesy of Clayton Early Learning

That school still occupies the historic Clayton College campus, where eight of the nine original buildings stand. The campus, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, sits just a few blocks southwest of the Park Hill Golf Club. Originally a dairy farm that was a separate part of Clayton’s estate, the land gave the first boys in the program the opportunity to receive agricultural instruction, but it now operates separately from the school.

According to records from Denver Public Library, in 1932 the farm was converted into the Park Hill Golf Club, which housed a city-owned eighteen-hole golf club, clubhouse and swanky restaurant open to the public; the land remained in the trust. In 1985, that trust was transferred from the city to Clayton Early Learning itself, which leased the course to manager Arcis Golf.

The golf course remained in operation until last year, when the city exercised an easement on the 25 northeastern acres for stormwater drainage. However, Clayton has been interested in selling the land since at least late 2016. According to Clayton Early Learning, it expected Arcis not to renew its lease, and organized a community meeting to invite public comments on the future of the golf course. But according to Garnsey, “It became clear that the basic premise was put forward in the first meeting that the land was going to have to be sold and bring $24 million to Clayton.”

When Garnsey learned that the land was subject to a conservation easement, he and neighbors began organizing to prompt the city and Clayton to abide by its terms. In the fall of 2017, though, the city and Clayton reached a complicated agreement that would allow the city to buy and develop half the land. After Arcis Golf sued to maintain its right to buy the land, that agreement was put on hold, and although litigation is still pending, Garnsey says it’s not clear whether any party involved has shown an interest in retaining the land for a golf course or a future park.

Clayton Early Learning confirmed, however, that the conservation easement would stay in place even if the sale goes through, and Denver City Council would have to agree to remove it.

Westside Investment Partners, which is trying to buy the property from Clayton Early Learning, is the same company poised to redevelop the historic Loretto Heights campus in southwest Denver into an affordable housing complex.