Fox31/YouTube

Audio By Carbonatix

Over the last six months, Aurora Mayor Mike Coffman has traveled to three cities, including two in Texas, to learn more about how other communities are managing homelessness.

Coffman’s first stop was in April at the Springs Rescue Mission in Colorado Springs. In September, Aurora City Councilmember Juan Marcano, a Democrat, arranged a fact-finding trip to Houston that Coffman joined, as did other metro Denver officials. And then in early October, fellow Aurora City Councilmember Dustin Zvonek, a Republican, led a trip to Haven for Hope in San Antonio; Coffman went along on that, too.

Since being elected mayor of Aurora in November 2019, Coffman, a Republican and former U.S. Representative, has taken a keen interest in homelessness, a problem that many metro mayors have historically viewed as a Denver-only issue.

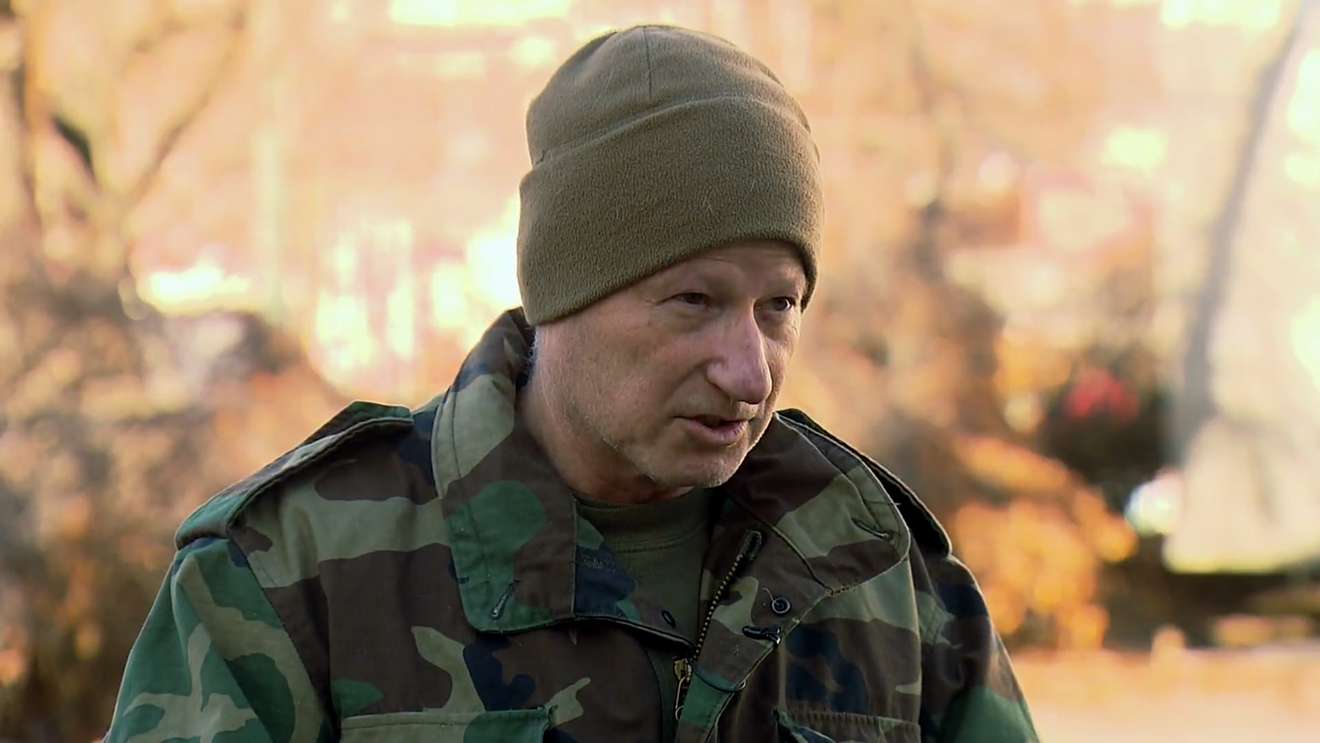

In late December 2020, just a few months after Coffman first floated the idea of establishing a camping ban in Aurora, he went undercover as “Homeless Mike.” Living on the streets of Denver, the former U.S. Marine slept under a tarp in an encampment, and also utilized the regional shelter system.

Coffman kept his mission largely a secret, but told CBS4 reporter Shaun Boyd what he was doing. Boyd interviewed Coffman before and after his stint on the street, and CBS4 filmed him while he was staying in an encampment.

“These encampments are not a product of an economy under COVID. They are not a product of rental rates, housing. They are a product of a drug culture,” Coffman told Boyd in the CBS4 story. The people he met in the encampments were not living outdoors because of a lack of shelter, he added: “Absolutely not. It is a lifestyle choice, and it is a very dangerous lifestyle choice.”

Coffman’s mission drew significant criticism from Democrats on Aurora City Council, as well as homeless service providers and other metro officials.

“While Mayor Coffman may have had initial purposeful intentions…you cannot just dip your toe in and out of poverty or homelessness. Homelessness is not a vacation for these individuals,” Eva Henry, an Adams County commissioner, said after the Homeless Mike story aired.

Mayor Mike Coffman went undercover as “Homeless Mike.”

CBS4

But Coffman has continued to study the issue of homelessness, as well as take action in Aurora. In March, he finally pushed the camping-ban proposal through council. And then the next month, he visited Springs Rescue Mission, which takes a different approach from the “housing-first” model that’s becoming popular in many cities.

Housing-first focuses on getting a person experiencing homelessness housed first, and then encourages that individual to deal with other challenges, such as getting a job or handling health and additional issues. In contrast, some service providers and governments require that people get jobs or get sober before providing much help, in what is sometimes categorized as a “work-first” approach.

“I think that the Colorado Springs program doesn’t take federal money, so they don’t have to adhere to a housing-first model,” says Coffman.

According to Coffman, the Springs Rescue Mission campus has multiple tiers: one for people wanting to access services and another one for people not interested in accessing services and only looking to obtain emergency resources. These two sections are located next to each other, so that people in the second tier might be motivated after seeing people in the first. A third tier offers a work-training program.

“They actually have a catering service that was pretty well-renowned in the Colorado Springs area, and people learned significant culinary skills in the program,” Coffman says.

In September, Coffman and other local officials visited Houston, which has garnered national praise for its housing-first approach to homelessness and was featured in a June New York Times article.

“What I was really impressed about was their ability to work with a single strategy and bring everybody on board – the city government, the county government, the nonprofits that are involved in homeless issues,” Coffman says. “They weren’t duplicating effort. They were very focused in a unified direction, and that was incredibly impressive.”

But Coffman was “disappointed” when he learned that Houston’s metric of success “was how many people after the 24 months [of housing] reapplied for services,” he recalls.

“They were pretty defensive about it. Their metric of success, that’s not a bad metric. But I think it would’ve been really nice to know that this is the disposition of people after 24 months. It kind of struck me as strange not to have that data, and to push back that it’s not relevant. I think that it is relevant,” Coffman says. For example, he adds, he’d like to know how many people were accessing addiction services.

Aurora has found that homelessness is not confined to Denver city limits.

Conor McCormick-Cavanagh

Then, earlier this month Coffman joined the trip to Haven for Hope in San Antonio.

“It’s a 22-acre campus with sort of separated parts for people just seeking emergency services from people in what they call transition who are accessing services, and then families in a separate part,” Coffman says. “I think what was impressive about it was to have the partners, people, other nonprofits co-located on the campus. Addiction recovery was right on the campus, a food bank was on the campus, medical services were on the campus. They were also not just available for people who were experiencing homelessness and were going there for that reason, but also for low-income individuals who were there accessing services.”

The Haven for Hope model – having all services on one campus – appeals to Coffman, he says. He also likes the element of having incentives for people to engage with services, a model that he saw in Colorado Springs.

“The San Antonio model has families experiencing homelessness on the campus, and I prefer the Colorado Springs model that partners with another nonprofit to provide temporary housing and services at a different location that exclusively serves families,” he notes.

Although he hasn’t visited them, Coffman has also looked at how other cities, such as Salt Lake City, are dealing with homelessness. And he’s studied programs closer to home.

In Aurora, Coffman is particularly impressed with Ready to Work, which puts homeless individuals to work while paying them and providing low-cost dormitory housing and case management. Run by the nonprofit organization Bridge House, it has space for fifty individuals, who pay up to one-third of their salaries on room and board.

“I think it’s a pretty good program,” Coffman says, noting that participants have to be sober and receive support in maintaining sobriety. “You have to work at least twenty hours from day one.”

Coffman is now working to incorporate elements from various programs into Aurora’s plan for homelessness resolutions.

“We have a mix of housing-first and work-first programs in the City of Aurora that are active or in the planning/development stages,” he explains. He also wants to build a homelessness services campus on land the city owns off East 32nd Avenue and Chambers Road; its potential price tag is estimated at $50 to $70 million.

“I will be pushing that the new campus that we are moving forward with aligns to a work-first approach,” he says. “It will provide emergency services for everyone, but we will focus our resources on those who want to change their behavior.”

But he also acknowledges that the city has a moral obligation to take care of people with severe mental issues or those “who are never going to want to participate in a program to get more stable.” A housing-first approach may be necessary in these situations, he says.

But first, there’s more studying to be done.