Conor McCormick-Cavanagh

Audio By Carbonatix

According to a new report, Denver is among cities in the United States with the most gentrification by neighborhood – and this isn’t a recent trend. The Mile High metro is the only area to rank in the top seven by this measure each decade for a half-century.

“Displaced by Design” was published under the auspices of the Washington, D.C.-based National Community Reinvestment Coalition, a network representing more than 700 nonprofit community development and finance organizations that seeks to “increase the flow of private capital into traditionally underserved communities.” And while gentrification happens in many parts of the country, Bruce Mitchell, NCRC’s lead researcher and the author of the study, notes that Denver stands out among all of the areas he analyzed.

“Denver has been a consistent city that has appeared on the list since the 1970s,” Mitchell says. “When we look at Denver from the 1970s and 1980s, we find a downtown core area that’s undergone gentrification, and it’s spread outside that core since then. Gentrification has been particularly intensive in Denver over the long term.”

For the latest survey, Mitchell points out, “we wanted to use a longer time frame and look at how gentrification has been impacting major cities over the past fifty years. We took data from 1970 to 2020 to see which neighborhoods in cities had been impacted the most by gentrification.”

Overall, he continues, “we found that gentrification is kind of rare. Only about 15 percent of urban neighborhoods have been impacted by gentrification. But where it does occur, it can be really concentrated and have a great deal of effect.”

The NCRC found gentrification was most evident “in major cities with a dynamic economy that have a downtown core area that is undergoing revitalization.” This description neatly fits Denver, which experienced significant growth over the period in question owing to a wide range of factors, including the construction of Coors Field, the development of nearby neighborhoods, and a commercial boom following the state’s legalization of recreational marijuana.

Nationwide, gentrification often results in what Mitchell describes as “a racial turnover in Black-majority neighborhoods.” He estimates that there are now at least 261,000 fewer Black people living in neighborhoods where that demographic was the majority in the 1970s, with total displacement of the group potentially reaching a half-million across the country. By sheer numbers, Denver contributed a relatively small portion of this amount – around 8,000 displaced Black residents, Mitchell says. But that represents well over 10 percent of the 62,785 Black people living in Denver in 2023, as counted by the U.S. Census Bureau, and involves a wide swath of the city.

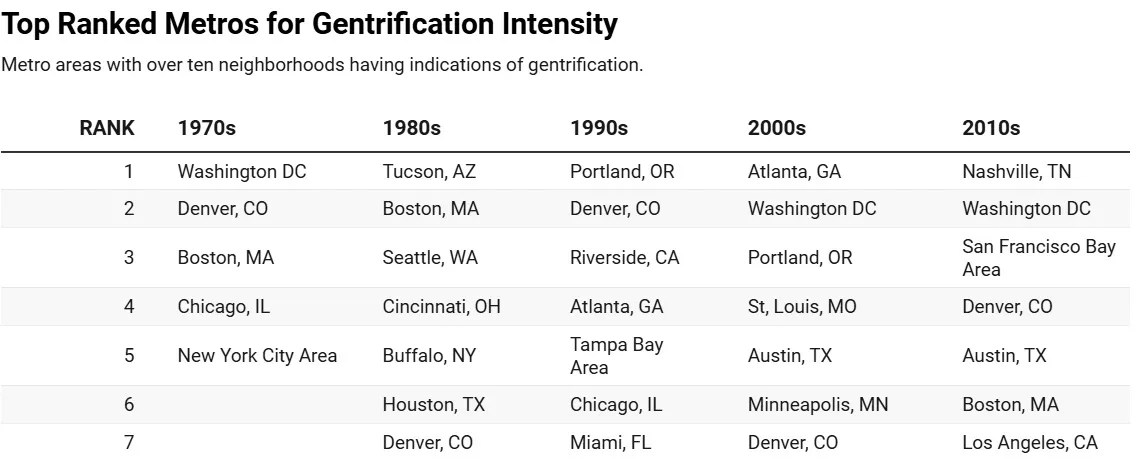

Such changes led to Denver’s high rankings on the NCRC’s roster of metro areas with a minimum of ten neighborhoods undergoing gentrification. As the chart below indicates, Denver is the only American city to meet this standard each of the five last decades, ranking second in the 1970s and 1990s, seventh in the 1980s and 2000s, and fourth in the 2010s.

The facts and figures behind the “Displaced by Design” rankings are graphically depicted by way of a fascinating and very user-friendly interactive map. The NCRC’s Jad Edlebi, who created the map, uses North Capitol Hill, also known as Uptown, as an example of how statistics are used to determine whether gentrification is happening in a given neighborhood.

Gentrification in North Capitol Hill

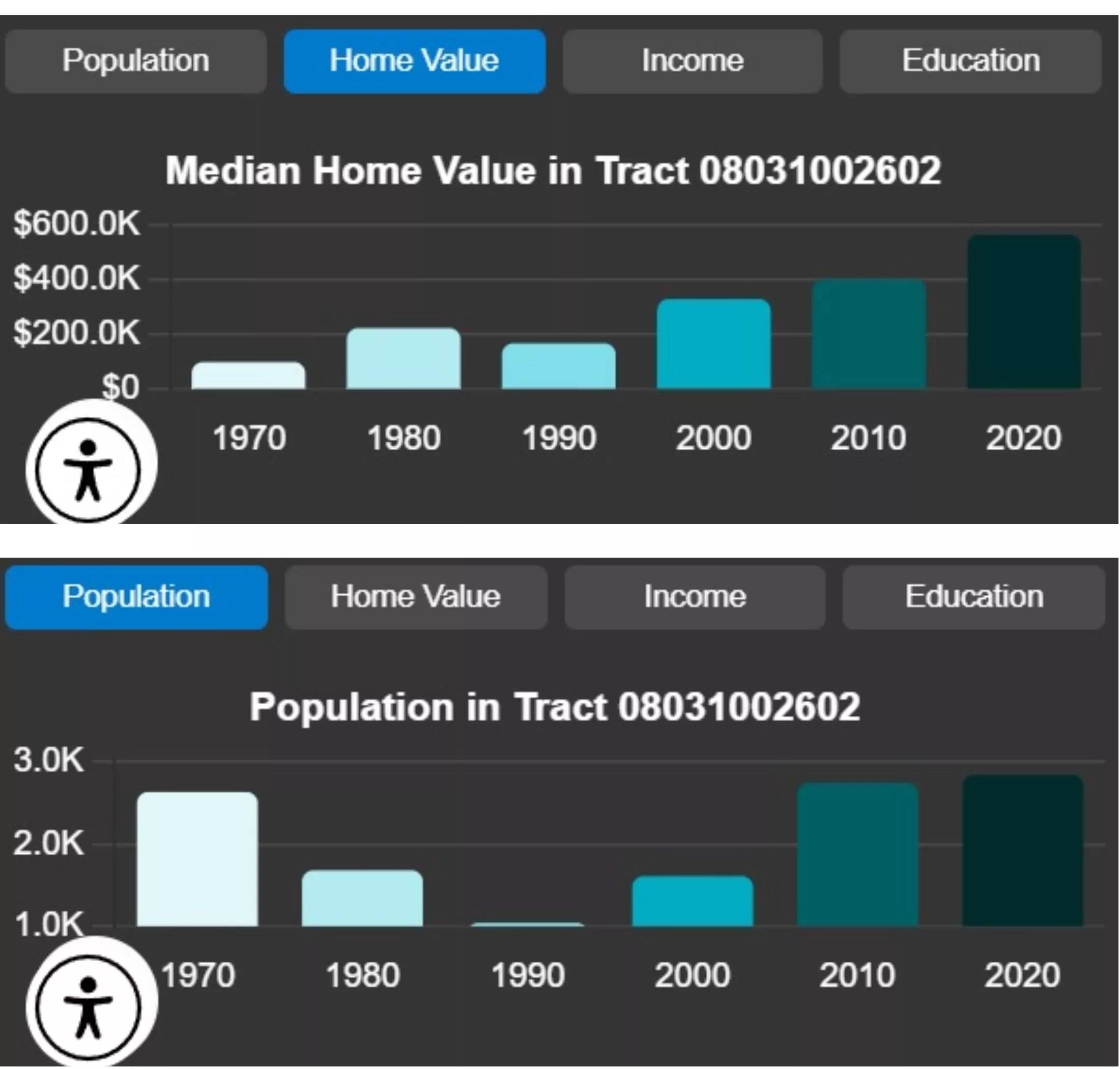

“When we notice the median home value of a census tract is below the 40th percentile, we deem an area eligible for gentrification,” Edlebi explains. “At the beginning of the 1980s, we determined that the economic conditions in North Capitol Hill were right for gentrification – and by the end of that decade, we saw median home value had increased above the 60th percentile. And we could already tell that there was a sizable increase between 1970 and 1980, because median home values more than doubled.”

This boost tailed off in the years that followed, only to be subsequently supersized, according to Edlebi. “North Capitol Hill actually gentrified twice – in the 1980s and 2000s. So in both the 1970s and the 1990s, we saw gentrification occurring, both times related to home values. But we also had a median income increase in the 1990s, and there are a lot of other scatter effects.”

Edlebi’s graphics show how deep the changes in North Capitol Hill run. The top item shows that median home values in the neighborhood were well below $200,000 in the 1970s, only to leap over that line in the 1980s. Median home values dipped a bit in the 1990s, but the second bout of gentrification pushed the price much higher in the 2000s, with the rise continuing in the 2010s. At the same time, as seen in the lower graphic, the population of the neighborhood dipped from nearly 3,000 in the 1970s to under 2,000 in the 1980s, and barely 1,000 in the 1990s. But gentrification 2.0 reversed matters, and by 2020, the population had exceeded the 1970s high-water mark.

According to NCRC, the median income of North Capitol Hill dwellers went on a similar ride, barely clearing $20,000 per annum from the 1970s to the 1990s before jumping up over the next twenty years; by 2020, it was nearly $100,000. Meanwhile, the number of folks in North Capitol Hill with a four-year college degree or more climbed steadily from the 1970s (around 10 percent) to 2020 (just shy of 80 percent).

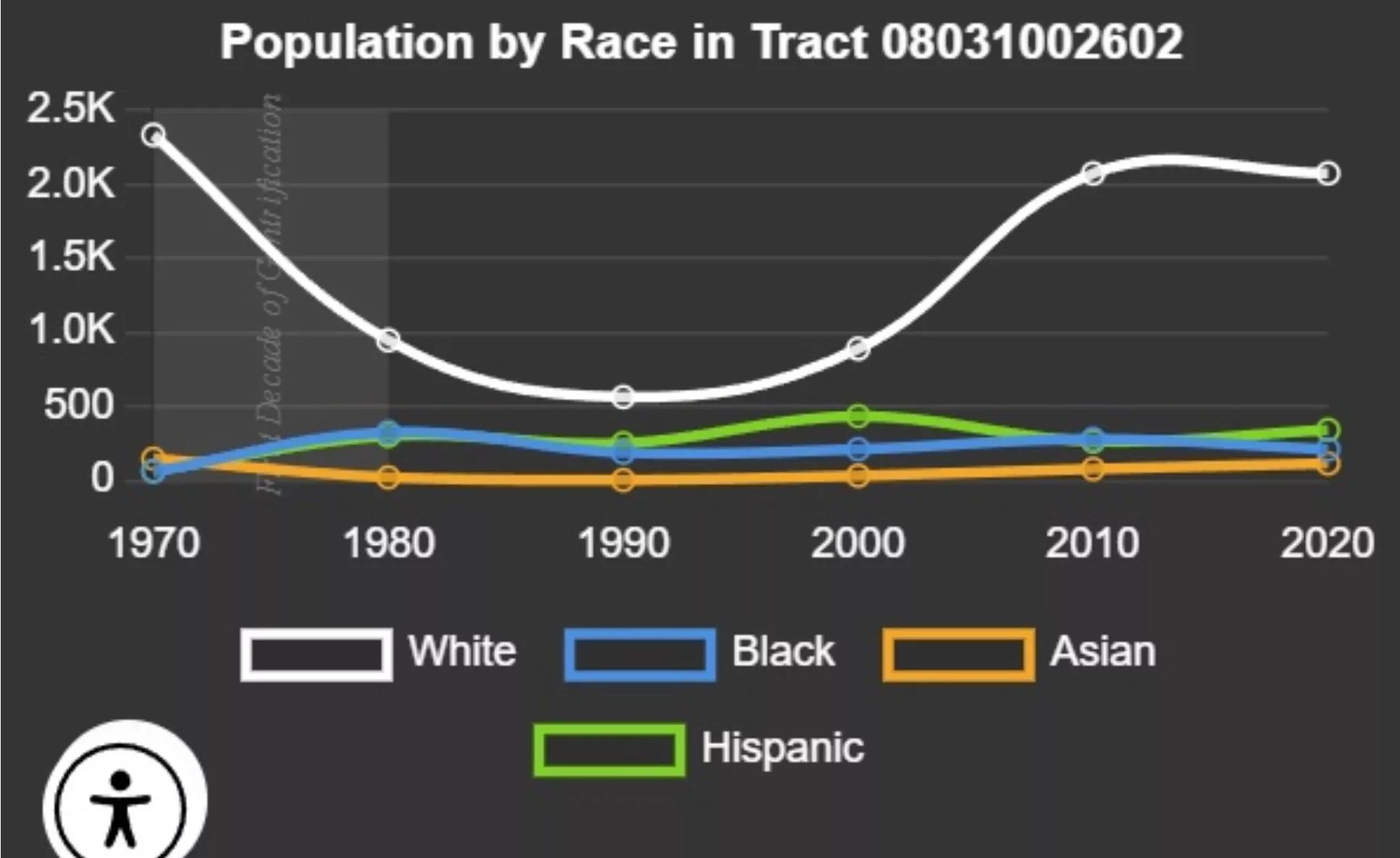

These changes were accompanied by radical demographic shifts. The map’s population-by-race graphic for North Capitol Hill shows that white residents left the neighborhood in large numbers from 1970 to 1990. But by 2020, they dwarfed other groups, whose modest populations tended to fall slightly or remain more or less static.

What Causes Gentrification in Denver?

As for the causes of gentrification, Mitchell divides them into two main categories: “My sense is that during the early time period, it was more organic, driven by individuals going into areas where property values were low but they had value because they were close to amenities like parks and the vibrancy of urban life. So they moved into those houses and rehabilitated them. But gentrification can also occur in a less organic way, where it’s more developer-driven. That’s when developers establish that areas of the city are ripe for this sort of revitalization and launch redevelopment on a massive scale. And I suspect that’s what’s been happening in Denver in recent decades.”

In such scenarios, Mitchell supports “policy measures to do something about this, particularly when gentrification is developer-driven and city planners are working with developers on this sort of change. It’s really crucial that the incumbent residents be fully involved in that process, and neighborhood organizations be fully involved in that process, too. Some of the things that can be done are homestead exemptions, so people living there aren’t priced out of the neighborhood, and there’s some accounting for affordable housing.”

Under these circumstances, Mitchell believes, “the people living in the neighborhood can participate in some of the good things that gentrification can bring – because gentrification can be very inequitable in the way people are impacted. The neighborhood may benefit the people moving in, but it can really be a detriment to people who have lived there and might have been renters, but are then priced out of the market.”