Audio By Carbonatix

Denver talk-radio legend Jay Marvin, who died on January 31 at age seventy, was one of the most courageous people I’ve had the honor of meeting. But the way he navigated his broadcasting career is only part of the reason he retains a special place in my heart.

Yes, Marvin remained stubbornly true to himself while behind the microphone, standing as a rare promoter of progressive values in a medium that has become a bastion of conservative thoughts and opinions. But his true character was revealed by his long battle with health problems, which prematurely ended his career but failed to squelch his restless imagination.

“Double Trouble,” a profile published by Westword in March 1998, tells Marvin’s origin story. He was born in Los Angeles but grew up in conservative Orange County, where he relocated when he was four or five. The move was precipitated by the split of his father, a talent agent whose clients included actors Valerie Harper, John Savage, Martin Sheen and Sally Kellerman, from his mother, who later was employed by an upscale chain of fashion stores. She soon remarried, but her new husband, a building contractor whom Marvin referred to as “Pol Pot,” did not become his dream dad. “My stepfather spent every waking hour telling me how stupid I was,” he recalled.

By the time he was a sophomore in high school, Marvin was heavily into self-medication. “You name the drug and I did it,” he recalled. “I even snorted heroin. And I drank. I’d do things like going to the dinner table on acid, because I couldn’t handle my family. In short, I was just very hostile and didn’t fit in – and I hated my household. My mission in life was to get out of there.”

Radio salved these wounds. He fell in love with the medium as a kid, thanks to the likes of the late Bob Crane, who was a disc jockey for KNX-AM in L.A. before he starred in Hogan’s Heroes, and his perspective broadened further in the early years of his adolescence after he was given a shortwave radio strong enough to pick up Radio Havana. “I fell in love with Cuba and Marxism,” he pointed out. “I was probably the only thirteen-year-old in Orange County who could raise his hand in class and tell you who the finance minister of Cuba was.”

In 1973, Marvin made a demo tape that landed him a gig playing country music at a station in Del Rio, Texas. But the job was only a pit stop; he skipped from one lousy position to another throughout the decade. Around this time, he married a woman as dedicated to substance abuse as he was, and although the relationship produced a daughter, Rachel, who was among the loves of his life, he didn’t find wedded bliss until betrothal number two. His second wife, Mary, became Marvin’s rock for the rest of his life.

At Mary’s insistence, Marvin gave up drugs and sought medical treatment. While living in Salt Lake City, where he’d moved in 1986, he was diagnosed as bipolar at what he called a “Dickensian” facility run by the State of Utah. But his troubles weren’t over. “They never got the doses right,” he recalled. “Some days my eyes would be like headlights, and other days I’d be drooling. Going through that taught me what a fucking crime health care in this country is.”

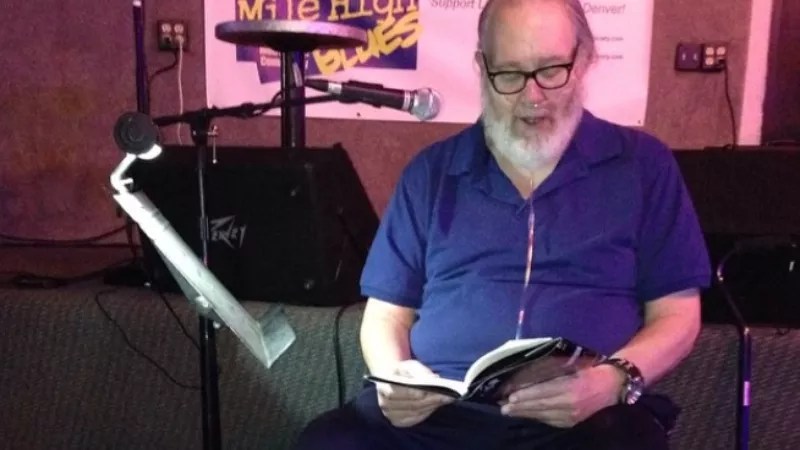

A promotional photo of Jay Marvin during his years with WLS in Chicago.

Courtesy of Mary Marvin

When Marvin moved to Florida in 1988, two significant changes occurred: He found a doctor who hit upon a prescription cocktail that didn’t completely erase his individuality, and he ventured into talk radio for the first time at tiny WKTN-AM, in the St. Petersburg-Tampa are in Florida. From there, he moved to nearby station WFLA-AM before making the leap to the big leagues: WLS in Chicago, whose signal could be heard in 38 states. His style, which combined jeremiads against post-Reagan Republicanism with ribald humor and filter-free anecdotes from his rebellious past, made him either a hero or a pariah, depending on who was listening, and that suited him fine.

When Marvin left WLS in 1996 to take a position at KHOW in Denver, rumors circulated that he had been fired, but he insisted that wasn’t so. He said he left on his own after WLS was sold to ABC, a network owned by the Walt Disney Company, which he charged with censoring controversial hosts. And while his radio approach proved to be as divisive in Denver as it had been in Chicago, he built a fiercely loyal fan base that followed him from KHOW to AM-760, a sibling station that employed a format dubbed “progressive talk.”

Then, in late February 2009, Marvin’s health took a precipitous downturn. He initially thought he had a case of the flu, but after several days of suffering, he entered the hospital and had his gallbladder removed. His severe pain remained, however, and after he was readmitted, doctors discovered that he was suffering from hepatitis – the kind associated with Budd-Chiari syndrome, a liver-related ailment generally caused by blocked veins.

To make matters worse, Marvin’s medical team discovered a large growth along his spine, in the vicinity of the T7 and T8 vertebrae. In an attempt to discover its makeup, they ordered a surgical biopsy that required them “to make incisions of three inches in front, three inches in back and an inch on his side,” Mary told Westword a few months later. They also had to collapse one of his lungs, leading to an extended stay in intensive care. “Synchronizing lungs after one of them has been collapsed can sometimes be tricky,” she explained.

Tests revealed that the mass was an anaerobic infection – one capable of growing without oxygen. In addition, Marvin had “osteomyelitis and discitis, which means there was an infection between the bone and the disc and the spine,” Mary said. “The T7 vertebrae crumbled or collapsed and was pushing on the spinal column at a 40-degree angle.”

An operation to address these issues was delayed as a result of the infection, leaving Marvin in limbo, and by the time physicians were able to move forward, a great deal of permanent damage had been done. Well over a year after those early flu-like symptoms, Marvin formally said goodbye to AM-760.

During the months that followed, Marvin’s ongoing issues pushed him to the edge. “I found him unconscious,” Mary wrote in an e-mail we quoted in a March 2011 post. “The paramedics couldn’t get a blood pressure, and his heart rate was 35.”

Marvin lingered in critical condition for several days, and even after he stabilized physically, Mary continued, “he was so depressed because of his chronic pain and no longer being able to work, he took at least 170 1mg Xanax. The doctors said the only reason he lived was because of the massive amounts of medicine he has had to take over the last two years.”

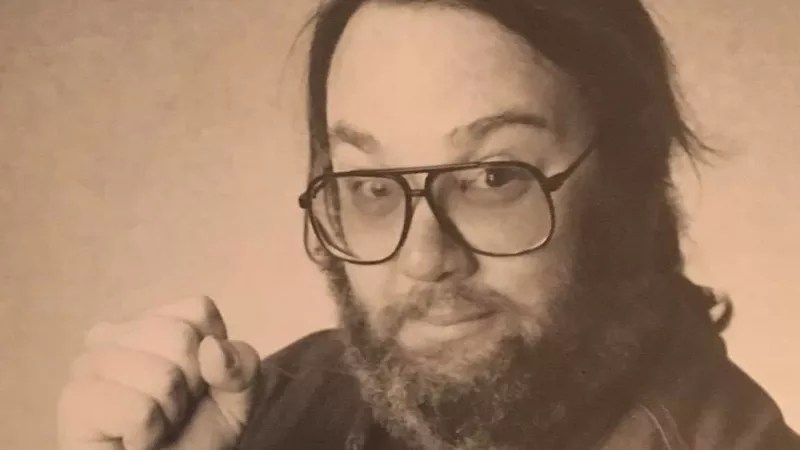

A photo shared on Twitter by David Sirota, left, for whom Jay Marvin served as a mentor and inspiration.

In a poignant note of his own, Marvin praised Mary and several doctors and staffers at Porter Adventist Hospital “for helping to save my life?”

Yes, the question mark was part of his message.

“No job after 36 years, chronic back pain, not knowing where I fit it in at 58 or what I’m supposed to do with my life, now that I can’t work,” he added.

Fortunately, he found purpose in poetry and, especially, painting. His artworks – a sampling of which can be seen on Instagram and Twitter pages – may be formally primitive, but they overflow with colorfully rendered emotions. “I’m an outsider artist, so I’m untrained,” he said in a 2015 interview before a local art show. “I just deal with life and try to make people smile. I love dogs, so I paint a lot of dogs. I paint angels that reflect death. It’s all about life and death.”

During that conversation, Marvin admitted that years had passed since he’d last tuned in to talk radio. The format “once was an entertainment medium, and you could do anything and everything,” he said. “But it turned harshly political and has become injurious to the country – so I’m glad I’m not a part of it anymore. Who’d want to do talk radio for four hours a day or night and only talk politics? I wouldn’t.”

Still, Marvin’s broadcasts have influenced many communicators from the generation that succeeded him, including David Sirota, who filled Marvin’s AM-760 slot after he stepped aside and went on to launch investigative-news website The Lever and also earn an Academy Award nomination for the star-studded Netflix offering Don’t Look Up. In an online tribute, Sirota wrote that Marvin “was an extremely important figure in my life journey – a person who showed an interest in me and gave me a chance to do something I had never done: host a drive-time radio show.”

Sirota added: “Jay always reminded me that in radio, you aren’t some grandiose orator talking to thousands of people, you are just a person talking to one other person in their car. He was an inspiration to me because he took the art of broadcasting seriously, and during the rise of right-wing talk radio, he never relinquished his values: He always took the side of the powerless against the powerful. I will miss him.”

Mary Marvin has not shared any information about services or a memorial for Marvin, but her brief online salute to the man she referred to as “my wonderful, loving, brilliant, talented, funny Jay” speaks volumes. She wrote, ‘You’ll always be in my heart and I’ll love you forever.”