Photo by J. Knight

Audio By Carbonatix

On February 27, 2009, less than two months shy of its 150th anniversary, the Rocky Mountain News published its final edition, bringing to an end one of the country’s last great newspaper wars and changing the journalism landscape in Denver forever.

In the ten years since, John Temple, the paper’s editor, publisher and president at the time of its closure, has worked on a fascinating series of endeavors. He was the founding editor and general manager of Honolulu Civil Beat, a news service funded by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar that Temple is proud to say is still going strong; served as president of audience and products for First Look Media, another Omidyar venture; and spent time as managing editor of the Washington Post. He’s also made his mark in academia – as a senior fellow in the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships program at Stanford University, and in his current gig as overseer of editorial projects and more for the Investigative Reporting Program at the University of California Berkeley. And, as if that’s not enough, he’s the chairman of Amuse Labs, a software firm whose signature product is a platform for digital crossword puzzles used by publications such as the Washington Post and the New Yorker.

Still, Temple hasn’t forgotten about Denver. He’s on the advisory committee of the Colorado Media Project, a University of Denver initiative intended to help conceive a new model for journalism during a period of tremendous upheaval. And early next month, he plans to return to the city for a Rocky reunion that will bring together survivors of what he calls “a very painful, very disappointing experience, and certainly the most traumatic professional episode of my life.”

Temple expands on this acknowledgment below in his own words, culled from a wide-ranging conversation. The topics he tackles include a joint operating agreement, or JOA, that linked the business operations of the Rocky and the Denver Post, its longtime rival, under the umbrella of the Denver Newspaper Agency; his initial optimism that the Rocky could survive; how the paper’s tabloid format undermined its chances despite its popularity with readers; the differing incentives of Dean Singleton, the Post‘s owner, and that of E.W. Scripps, parent company of the Rocky; the first major sign of doom; a survival mission inspired by the way the Las Vegas Sun was once inserted into the Las Vegas Review-Journal; the reasons a buyer for the Rocky couldn’t be found; impressive achievements as the curtain was about to drop; and the tremendous impact of the shutdown on Rocky employees and everyone in their immediate circle.

In addition, Temple weighs in on the decline of the Post in recent years, complete with some especially harsh words for Alden Global Capital, its vampiric hedge fund owner, and suggests that the death of traditional newspapers might actually be good for journalism in general. But he begins by reflecting on what went down a decade ago.

Former Rocky Mountain News reporter Lynn Bartels surrounded by press after the announcement that the paper would be closing.

Photo by J. Knight

“It feels very fresh and it feels like a long time ago. It feels like both. I still feel very close to the people I worked with at the Rocky. So much has happened since then to me personally and in the industry that it’s really receding into the past. But that obviously depends on which part you think about. If you think about the traumatic ending of the Rocky, that’s one thing. But I was there for seventeen years, and when I think about all we were able to do as a group and as a team, that’s a different thing. It’s complicated emotionally.

“The war really ended in 2001, when the JOA was formed. After that, we were in a different state, I think. But we always tried to do the best journalism we could. I think the Rocky was, in many ways, ahead of its time, and we did fantastic work that I’m still proud of to this day.

“In terms of my optimism, I’m an optimistic person. But we also clearly had the loyalty of the audience on our side. The Post had similar research. People in Colorado, but particularly people in the metro area and along the Front Range, liked the Rocky more. They had more affection and loyalty to the Rocky than to the Post, and it was for reasons that were really humbling to a journalist.

“The tabloid format of the Rocky was much more reader-friendly than the Post‘s broadsheet, just like an Android or an iPhone are more friendly than sitting at a desktop computer. And from an editorial-quality standpoint, and from a reader-relationship standpoint, I felt there were good reasons to be optimistic, too. But at the time, the tabloid format ultimately proved to be a total barrier for the Rocky from an economic standpoint.

“Both publications were under the JOA, and they were largely dependent on print advertising – and that put the Rocky at a disadvantage, because of the size of the page. A full-page ad in the Rocky was seventy inches, and a full-page ad in the Post was 120 or 126 inches. That meant the same ad in the Post made much more, and that applied to the JOA generally. When the Post sold a full-page ad, the Denver Newspaper Agency made more money. So effectively, the format that had to survive had to be the print format that was better at producing ad revenue – and that was the broadsheet.

“You can say the demise of the Rocky was due in part to the lack of imagination and the sort of courage of us as leaders doing radical things. For example, we had two websites that diluted and duplicated. We produced a lot of duplicative costs by doing that. And it made no sense to run a broadsheet Monday through Saturday. Historically, 50 percent of the advertising revenue in a week was on Sunday. That’s when you needed the larger page format to make more revenue. But that’s all water under the bridge. The fact of the matter is, the Rocky‘s format was a great strength for the reader and a great detriment to ad revenue. And that meant the broadsheet would win.

“Dean Singleton had a great reason to stay in Colorado and own the Post – to stay in the market. And Scripps didn’t. Scripps had a reason not to be in the market. They saw the losses that were ahead of them, and Dean followed his own strategy. The result was the demise of the Rocky.

“If you remember, 2008 was a very difficult economic year – but that was the year I started a political website called redblueamerica.com. I ran it out of the Rocky, but we were actually a dispersed team. I had people all over the country working on it. It was a national web initiative by Scripps that was based on work I’d done in 2006 and 2007 to prepare for it. Scripps invested a serious amount of money in it, and we hired a team and launched in 2008. But maybe four months later, I was notified by Scripps that I needed to shut it down because the economic conditions were worsening so drastically and they were pulling back from all newspaper ventures. That’s when I knew things were very, very serious.

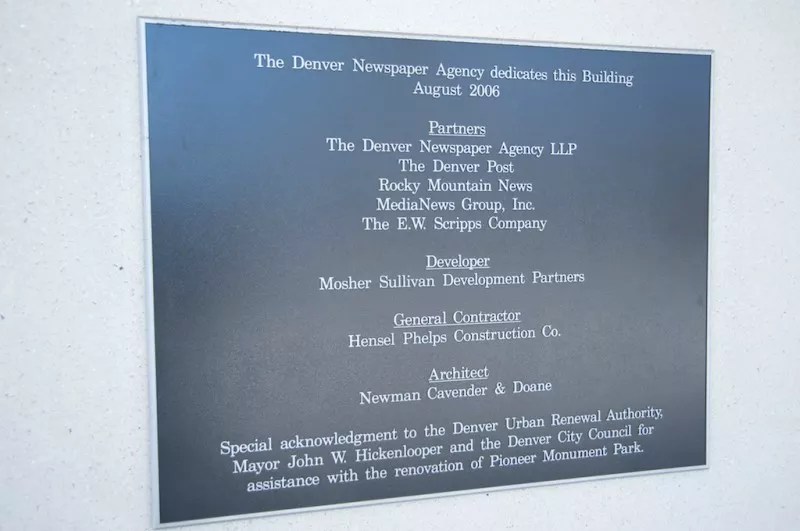

A sign in the former Denver Post headquarters building that lists the various partners in the joint operating agreement.

Photo by J. Knight

“That was probably the first serious blow, and I can tell you, it’s never fun shutting down something like that – even a website that we’d started only four or five months previously. I’d put a lot of work into creating that, so it was a bad experience.

“Seeing what the world looked like, we knew the model wasn’t working in Denver. And I don’t know if this has ever been reported, but I took a trip to Las Vegas and spent a day at the Las Vegas Sun to evaluate if there was a model based on Las Vegas where we could keep the two newspapers alive by inserting some version of the Rocky into the Post – creating a better product by sort of integrating the two. They would be separate but together. I spent the day in Las Vegas exploring this with the people there. So that was another indication that we were looking for a solution.

“Then, when the paper was put up for sale [in December 2008], I knew it was incredibly serious. There were only a few outcomes possible. A sale, which could be good, but it would have more likely been bad, because we would probably have had to cut dramatically. Or closure. Or status quo, because they backed off – but I knew status quo wasn’t a long-term solution.

“I did have to work with a broker to provide a lot of information about the Rocky and its situation and what made it special to potential buyers. And I knew the challenges that buyers saw in that particular deal. Fundamentally, the challenge was that it was a 50-50 partnership, which means you’d be buying into something that you couldn’t control. And most investors don’t want to buy something they can’t control. That was a serious problem. We needed a dominant partner, and because of the JOA, there wasn’t one.

“There was one buyer who thought he could make it work. But you have to remember, there were three players in this. There was Scripps, there was Dean Singleton, and there was the prospective buyer. You didn’t just have to deal with Scripps. You also had to deal with Dean – and I don’t think that was a realistic possibility. There were days I thought something might happen, but it didn’t.

“In the meantime, because the sale had been made public, we began holding weekly meetings in the newsroom to make sure the staff had as much information about the situation as possible. Even if I had no information, I would rather take questions and make sure we were talking. That was tough. But one thing I’ve always tried to do in my career, whether times were good or bad, was to focus on the journalism. And that was an incredible time. We’d had the Democratic convention in Denver, and that was a high point for the Rocky Mountain News. It was an incredible effort by our team, and all the coverage leading up to it. We had a reporter in Iowa, M. E. Sprengelmeyer, who was blogging for the web in a way I thought was really interesting and that people weren’t really doing in 2008. We just thought, fuck it. We still have access to this printing press, and we can still publish online, so let’s go for it. If we were going to go down, we were going to go down swinging.

“We were also working on a major project that was one reason why we were able to have what I think was an incredible final edition. In the fall of 2008, I was planning the 150th anniversary of the Rocky Mountain News, which was the first newspaper in Colorado. William Byers, the founder of the Rocky, was really one of the people who created Colorado. We wanted to do a lot of things around our anniversary, so by that fall, we were prepping for publication six months later. I knew that maybe we wouldn’t get there, but I knew it was better to be working on it and understand more about our history.

“The other thing we did was decide to do a documentary about ourselves. We had Sonya Doctorian, a great member of our photo team, who had a master’s degree in documentary filmmaking, and we decided to make it and publish it whether we were sold or closed, just to show a newspaper going through the process, how it affected the staff and what the news organization meant to the community and to its readers. We knew that I might not be the editor when it came out because, as the editor and publisher, I was clearly the person a new editor would potentially fire. So we needed to publish it while I was still employed. That meant publishing it immediately upon the announcement.

“I also gave Max Potter from 5280 complete access to do a story about what was happening. I said, ‘There are a few meetings you can’t be at – but have at it.’ I wanted an independent person to capture what I thought was important. He ultimately thought something different was important. But I thought the newspaper had a unique relationship with the community and that capturing it independently would be really valuable both from understanding a local news organization and understanding what the Rocky had been in the community.

“As the announcement got closer, those were really tough days. One thing you learn when you go through a sale or the closure of an organization is how it’s not just about the people who work there. Of course, there are people behind the newsroom, people in pre-press and advertising and delivery and circulation – people all over the product. And for most journalists, at least part of their identity is tied up in their job. But what I didn’t realize was that the identity of their family was tied up in their job, too.

“There were mothers and fathers proud of a daughter working for a newspaper and proud of the community contribution their child was making. And there were spouses who had health-care issues, there were children who were about to go to college. The list goes on and on. The ripple effect is so much larger than the 200-odd people who were ultimately going to lose their job. It’s huge. And the people in the newsroom weren’t just experiencing the trauma and loss themselves. They were caring for loved ones who were experiencing it, too.

“The people who worked at the Rocky were committed, and they had a certain kind of ethos. The Rocky was very unlike other newspapers. When people were hired, I would give them a one-page sheet that I literally called ‘The Essence of Rockyness,’ because I wanted them to understand that this was a news organization with certain values and a certain character. It wasn’t a generic news organization, and I wanted them to understand what made the Rocky the Rocky.

“There was a commitment on my part to them. We were a sort of family, and since the Rocky closed, I’ve tried to help people get good employment. I continue to be a reference for people ten years later. Just the other day, I received an email from a person who’d worked at the Rocky asking me to be a reference on a job.

“But for me, it’s taken me years to really understand how traumatic it was. It was a very painful, very disappointing experience, and certainly the most traumatic professional episode of my life. It’s something I don’t wish upon anybody. It lives with me to this day. There’s no question about that.

A recent photo of John Temple.

“When I was a kid, I clipped my lip, and sometimes I can feel where it happened. I bite my lip because the wound is still there. I use that analogy for the Rocky. The wound of the experience of the Rocky is still with me. I still feel it. It’s affected my career and it’s affected how I feel about things – sometimes in good ways, but other times in very bad, painful ways.

“When the Rocky closed in 2009, I don’t believe anybody imagined that we would be where we are today – and where the Post would be today. The Post was very profitable, and I certainly think Dean Singleton believed the Post would continue to be very profitable as the only newspaper in Denver. But I don’t think anybody believed that for it to keep being profitable, it would have to be gutted and become a ghost of itself. I think it’s just devastating.

“I was incredibly impressed by the insurrection at the Post last year. I really appreciate the courage of what the people did there. I don’t mean to say the people working at the Post today aren’t trying to do their best. I’m sure they’re approaching their job the way we did at the Rocky in the final days. But it’s incredibly depressing what’s happening to the Post and Media News Group. I think all of us, as leaders in the newspaper industry, bear some responsibility for the failure of the industry. And now that I’m outside the industry, I look at it and think, why would anybody with technical chops join the newspaper industry? What a foolish decision. I mean, come on. Why would you be in tech and work at any newspaper except the Washington Post or the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal or, prospectively, the L.A. Times? I just don’t see it. It’s very depressing. I think it has big consequences for us as a country. And I don’t know the answer.

“I don’t believe the future is newspapers. I just don’t believe that’s how people are going to consume information. But I don’t think Alden Global Capital thinks of the Post as a newspaper. They think of it as a cash register, a financial machine, an instrument to make money. They have no interest in the reader. Their point is to suck the thing dry and abandon it. And in some ways, the sooner that happens the better, because then new properties can come up. We’re kind of in a forest fire, and after a fire, the grass grows very quickly and all kinds of new growth occurs. I think in some markets, the owner is literally lighting the fire – reaping anything they can suck out of the newspaper.

“I’m not saying all newspaper properties and all newspaper owners are operating that way. But clearly, Alden Global Capital is. And afterward, there’s going to be something different.

“We’re holding a reunion of people who worked at the Rocky. It’s going to be on March 9, and we’re going to mark the 160th anniversary of the Rocky Mountain News and the ten-year anniversary of the closing. It will be an opportunity to see old friends and remember people we’ve lost, because some of our staff has died in the meantime. But I’m really looking forward to it, and I’ve been thinking a lot about it. It’s sad on one level. But I’m really lucky I’m able to do it and that I’ll be able to reunite with my former colleagues. We went through so much together.”