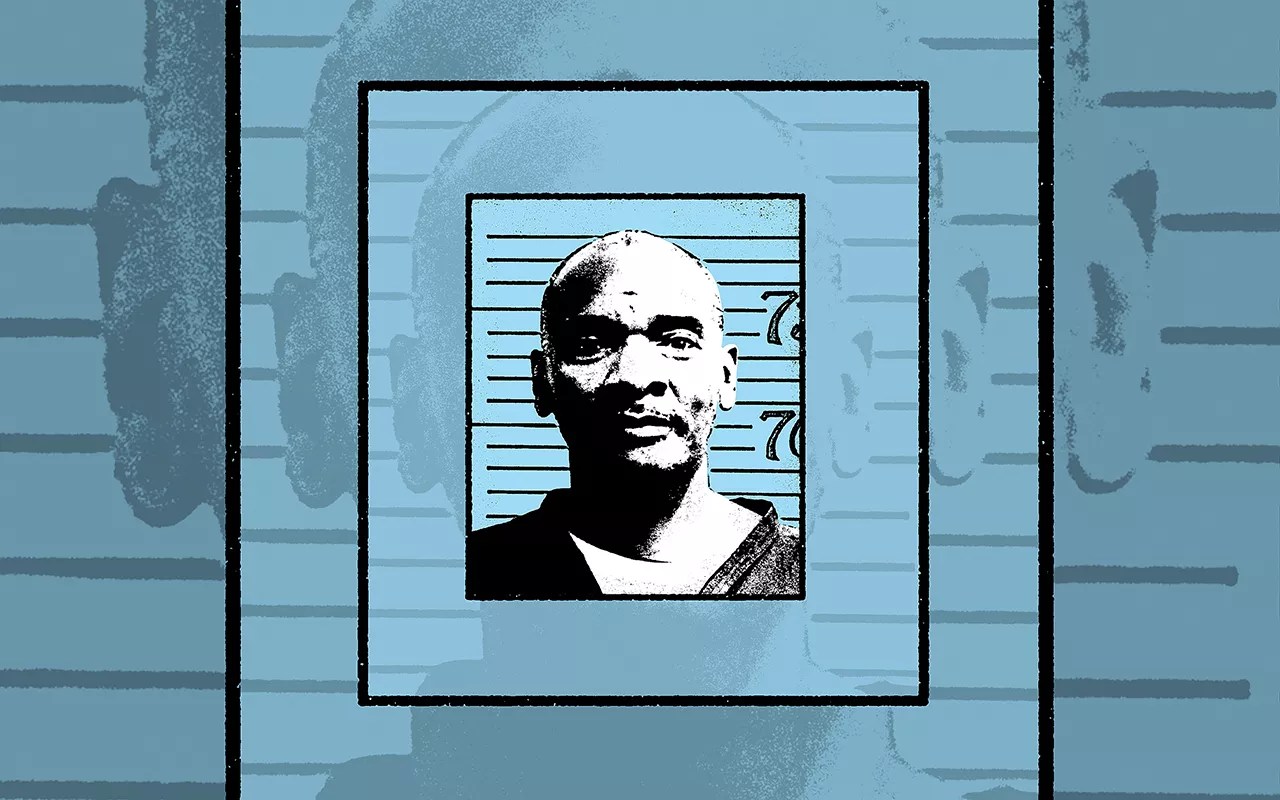

CDOC/Westword photo illustration

Audio By Carbonatix

Freddie Glenn is nervous. He sits tensely in a small room at the Fremont Correctional Facility, gazing into a monitor at the faces of the three Colorado Parole Board members who are conducting this virtual meeting and hold his fate in their hands. This is Glenn’s fourth parole hearing in thirteen years, and he’s finding it every bit as difficult as his first one.

The questions are always the same. They want to know his date of birth and his inmate number. Then they want him to account for things that happened nearly half a century ago. They want him to explain his role in three murders that occurred over a twelve-day period in 1975, three killings so random and pointless that they left hard-nosed cops and prosecutors shaking their heads in disbelief. “There was no rhyme or reason for what happened,” concluded Judge Hunter Hardeman, who presided over Glenn’s trial.

But Glenn is expected to offer reasons, the how and the why. So he begins: “I was seventeen years old when I came to Colorado Springs. I did everything right. I got a job at Fort Carson. I had an apartment. I had a car. I had never been in trouble in my life. I got involved with two guys…I wish I had never met them.”

It’s an old story, one Glenn has told many times. But not always the same way.

“There was no rhyme or reason for what happened.”

Glenn will turn 66 in a few weeks. He is by no means the oldest inmate in the Colorado Department of Corrections, but his 47 years behind bars make him the second-longest-serving prisoner in the system. He has been eligible for parole since 2006, but in his case, the possibility of being released from prison has remained an entirely theoretical concept, like the possibility of travel to another galaxy.

The problem isn’t his behavior behind bars. Glenn is considered a model prisoner; he’s taken every rehabilitative program available to him, studied everything from carpentry to the habits of successful people, and has mentored many other inmates. He’s had no disciplinary write-ups in decades, prompting parole board member Darlene Alcala to remark, “You’ve done your time well.” Yet his application for parole has been denied again and again.

What matters is what happened back in the summer of ’75, when Glenn and the two guys he wishes he’d never met, Michael Corbett and Larry Dunn, embarked on a crime spree that terrorized Colorado Springs, a horror show with a shifting cast of participants that was eventually linked to at least five deaths. One man was shot in the head for the spare change in his pocket. Another was bayoneted in a ten-dollar drug deal. Those killings were soon followed by what would become the most infamous of the lot: the abduction, rape and murder of Karen Grammer, an eighteen-year-old restaurant worker – and the younger sister of a then-unknown actor, Kelsey Grammer.

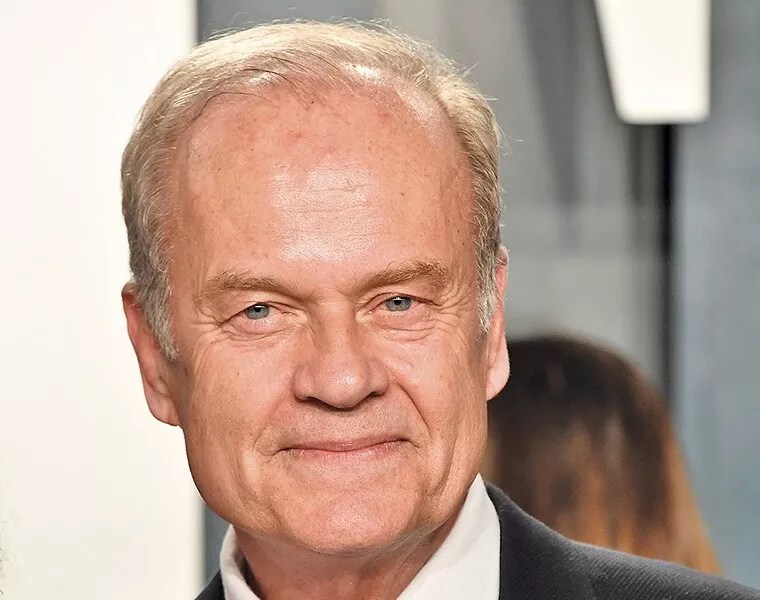

Grammer’s subsequent success in sitcoms and movies has cast a national spotlight on his sister’s violent death. The tabloid press has followed closely as Grammer has addressed the parole board, either by video or email, each time that Glenn, convicted of her murder, is up for release. The Frasier star has called Glenn a butcher and a monster. He has also declared that he forgives Glenn but doesn’t want to see him released. “To give that a blessing would be a betrayal of my sister’s life,” he said in 2014.

Whether Grammer weighed in on Glenn’s most recent hearing is unknown; the parole board now treats all victim testimony and statements as confidential and excludes them from the “public” component of the hearing. (Grammer didn’t respond to a request for comment.) But having a celebrity adamantly opposed to his release can’t help Glenn’s chances. He’s stuck in an endless loop, even as the facts of the case and his particular role in the killings become more muddled with age. Glenn has outlived his two principal co-defendants, as well as the detective who broke the case and the district attorney who prosecuted him. What he can’t outlive is his life sentence, even if it does include a hypothetical prospect of parole.

His supporters maintain that Glenn was not directly involved in any of the murders for which he is serving time, that he was essentially a pawn of two highly lethal, manipulative predators. After all these years, there are several versions of the story to choose from, compounded by slipshod reporting. None of those accounts absolve Glenn, but they do raise a difficult question for the parole board, wrestling with one of the oldest cases on its books: How long is long enough?

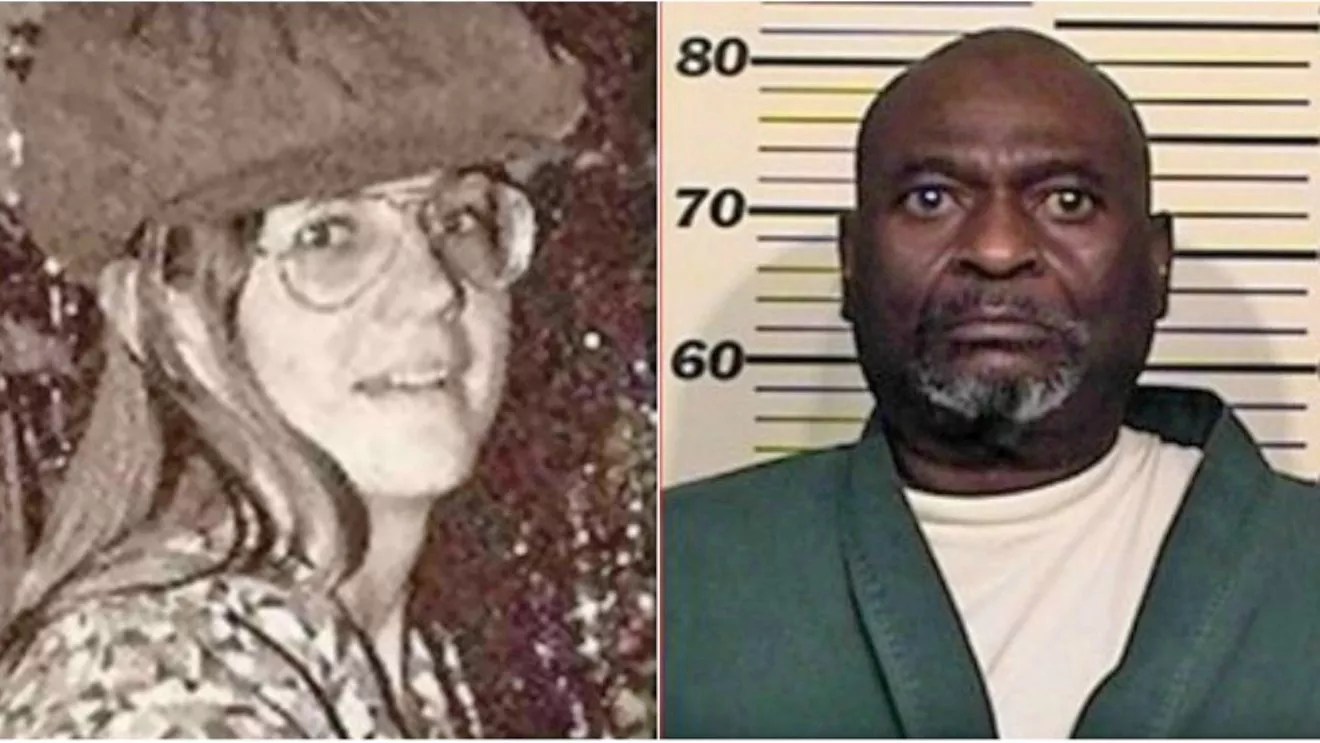

Karen Grammer was the third victim in a series of 1975 murders in a killing spree led by Michael Corbett.

Murdepedia/CDOC

Freddie Lee Glenn arrived in Colorado Springs in the fall of 1974, fleeing what he would later describe as an abusive situation at home in St. Petersburg, Florida. His father drank and beat his mother. Seventeen-year-old Freddie tried to protect her and got beat himself. His father declared that Freddie had to go or he would kick them all out, including Freddie’s mom and his sisters. Freddie went.

He had an aunt who worked in food services at Fort Carson. He stayed with her a few weeks, then found a civilian job at the base and moved into an apartment house that was full of Fort Carson people, including GIs not much older than Glenn. The fact that Glenn had his own car, a white Oldsmobile, made him a popular fellow; many of the soldiers couldn’t afford their own wheels and were often dead broke.

Glenn began hanging out with Michael Corbett and Larry Dunn, two of the Army guys he met in the apartment house. Corbett was nineteen and seemed to have a fascination with violence; Dunn was in his thirties and had been to Vietnam – where, it was said, he’d seen things that messed with his head. Glenn gave them rides in his Olds, got high with them. “It started out okay,” he later recalled. “Just young guys smoking weed, playing music.”

But one night Corbett and Dunn began talking about wanting to pull a robbery to alleviate their chronic lack of funds, and needing transportation to make the robbery happen. After drinking some wine, smoking some weed and taking two hits of LSD, Glenn agreed to drive them. He took them to the Four Seasons Motor Inn. He stayed in the car while Corbett and Dunn strolled across the parking lot.

Glenn was surprised when they returned not with the motel’s receipts, but with a 29-year-old man named Daniel Van Lone. A cook at the motel, Van Lone had been getting into his car when Dunn ordered him at gunpoint to come with them. They put him in Glenn’s car and blindfolded him with a scarf provided by Glenn. Van Lone had only fifty cents on him.

“Did you ever hear of anybody dying over fifty cents?” Dunn asked him.

“Yes,” Van Lone replied.

They took him to an isolated road. Glenn stayed in the car. Corbett and Dunn forced Van Lone to lie on the ground. Corbett killed him with a single shot to the head. He would later brag that he “blew a dude’s brains out” because the man could identify him.

Eight days later, Corbett was approached by another nineteen-year-old soldier, Winford Profitt, who was looking to buy ten dollars’ worth of marijuana. Corbett arranged to meet him at Memorial Park. Glenn drove him there and remained in the car while Corbett went into the park. Corbett later admitted to stabbing Profitt to death because, he said, he wanted to know what it felt like to kill someone with a bayonet.

Three days after Profitt’s murder, on June 30, 1975, Glenn partied well into the evening on wine, weed and acid. A friend who dropped by recalled that Glenn “just seemed like he wanted to get super high.” Or maybe he was preparing himself for another chauffeuring expedition. This time his passengers were Dunn and another soldier, Eric McLeod, who were intent on knocking over the Red Lobster on Academy Boulevard that night. But once at the restaurant, McLeod and Dunn lost their nerve. Instead, Dunn abducted Karen Grammer, who was waiting outside the Red Lobster for her boyfriend to get off work. Fearful that she might be able to identify them, the two men took her to Glenn’s car at gunpoint and told him to take off.

Glenn stayed in the car with Grammer while Dunn and McLeod robbed a 7-Eleven, emerging with $60 in cash and some cheap jewelry. They then went to McLeod’s apartment, where Grammer was repeatedly sexually assaulted. Although she pleaded for her life, the three men took her in Glenn’s Olds to a dark alley, where she was stabbed in the throat, back and hand. She managed to stagger to a nearby trailer park, where her body was found the next morning.

Glenn distanced himself from Corbett and Dunn after that night and soon moved out of the apartment house. But the crimes didn’t stay unsolved for long – largely because Corbett went on killing people and bragging about it. Three weeks after Grammer’s murder, Corbett shot Winslow Watson III in the face over a stolen loaf of bread. A few weeks after that, he was arrested and charged with a shotgun slaying at a bar. He was suspected but not charged in several other high-profile crimes. Pressure was brought to bear on Larry Dunn, who struck a deal for immunity in exchange for testifying against Corbett and Glenn.

Glenn, too, was offered a plea bargain if he would testify against Corbett; the deal would have landed him a ten-year prison sentence. But Glenn claimed to be deathly afraid of Corbett – that was why, he insisted, he’d continued to drive for him after the first robbery went bad – and didn’t want to enter the prison system branded as a snitch. So Dunn became the star witness against the others, despite having participated in the murder of Van Lone and the abduction and rape of Grammer. Based largely on Dunn’s testimony, Glenn was convicted of killing Grammer. (Glenn’s attorney would later acknowledge that he had “handled very few criminal cases” and mainly represented personal injury clients.) Both Corbett and Glenn received death sentences. McLeod pleaded guilty to rape and armed robbery and got fifteen to twenty years.

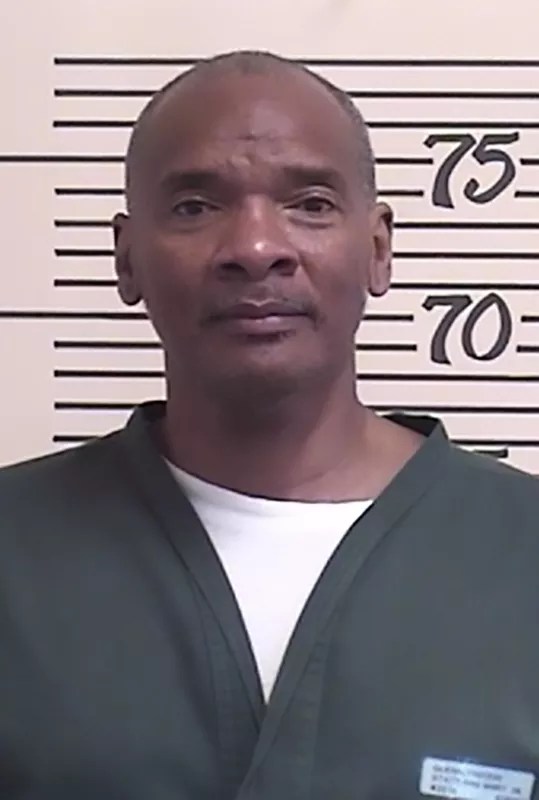

Freddie Glenn was sentenced to life in prison.

CDOC

In 1978, Colorado’s death penalty was declared unconstitutional, and the spree killers were resentenced. Glenn received three ten-year-to-life consecutive sentences for the murders of Van Lone, Profitt and Grammer – which, under the sentencing scheme in place at the time, meant that he would be eligible for parole after serving thirty years. (The 1978 ban removed seven inmates from death row; in 1979, state lawmakers reinstated the death penalty, though only one execution took place in the next four decades before the penalty was abolished in 2020.)

From the outset, Glenn maintained that he hadn’t killed anyone, that he was just “the dummy with the car” who waited in the Olds while the others committed horrible crimes. He was never charged with the rape of Grammer and denied stabbing her. But under Colorado’s felony murder law, someone who participated in a felony – by, say, driving a car to a robbery – could be found just as guilty of a resulting death as the person who actually did the killing. (Last year the law was changed; it now limits the sentence to that for second-degree murder rather than first-degree.) And the absence of a sex-crime conviction didn’t deter the Department of Corrections from classifying Glenn as a sex offender, complicating his life inside.

In prison, Michael Corbett converted to Islam and changed his name to Hasani Chinangwa. He wrote letters supporting Glenn’s version of events, taking sole responsibility for the Van Lone and Profitt murders and accusing Dunn of killing Grammer. He died of kidney failure in 2019, still serving multiple life sentences. Dunn had died several years earlier in a Louisiana prison. Now only Glenn remains to tell the tale.

But the tale keeps evolving. When Glenn first appeared before the parole board, in 2009, he had some testy exchanges with the panel about what his role had been in the murders. When he came back five years later, he had decided to take the advice of a clemency consultant, who urged him to take the blame for Grammer’s killing because that was what the board needed to hear. After the hearing, Glenn wrote a letter to Kelsey Grammer, saying that he was ashamed of his performance and wanted to explain “what really happened.”

“I apologized to you for the loss of your sister during my hearing, and I meant every word of it from my heart,” he wrote. “I am so sorry that you have had to live with that pain and hatred for me. … Had I cooperated and saved myself and told them Larry Dunn killed your sister and testified against Michael Corbett, I would not be in prison today. Larry Dunn took the life of your sister and was actively involved in the other two murders.”

The contradictions in Glenn’s story were on display again at his latest hearing. “I stabbed Ms. Grammer,” he told the boardmembers. “I accept full responsibility and hold myself accountable for the death of Ms. Grammer. I do.”

But then he went on to equivocate, noting that the felony murder law made him “as guilty as the person who committed the murder.” That prompted the boardmembers to press him to be more specific about what he did or didn’t do.

“I do have some concerns about his minimization of his crimes,” said board chair J.R. Hall, a retired deputy sheriff. “I would like to hear him take ownership of the crime.”

“I would like to hear him take ownership of the crime.”

“The police report says you killed Ms. Grammer and that she was raped by the three of you,” observed boardmember Alcala. “We want to know what you take responsibility for. What was your part?”

Glenn was adamant. He didn’t take part in any rape. As for the killing, he explained that Dunn was supposed to let Grammer go. Dunn took her out of the car, he said, and was trying to untie her hands; he asked Glenn to get out and help him. And then, looking back into that abyss, Glenn faltered.

“There was a struggle,” he said. “There was a panic…I don’t remember stabbing Karen Grammer. We were on acid. We were high…but I accept responsibility.”

On other phases of the examination, Glenn fared well. He had done everything he could to try to make up for the damage he’d caused, he said. He had helped other inmates turn their lives around. He had many letters of support. He had family, a home, a job waiting for him in Florida. And he had a few questions of his own. “What purpose would be served by further incarcerating me?” he asked. “Why should I be exempt from receiving a second chance?”

In Colorado, a state prisoner seeking parole who is convicted of a violent crime must undergo what is known as a “full-board review,” a process that actually requires participation by only four of the nine parole board members. The record of Glenn’s hearing this fall was submitted to a fourth boardmember. After deliberation, the board decided that he had “untreated criminogenic needs” and denied his parole.

He can apply again in five years.

Kelsey Grammer has said he forgives Freddie Glenn for his sister’s murder but doesn’t want to see him released.

Getty Images/Frazer Harrison

Whatever consolation the board’s decision might have been to the victims’ families, it was crushing news to Glenn’s surviving siblings and other supporters, including the woman he calls his fiancée, Belinda Gardner.

Glenn met Gardner in 1975, when Gardner was fifteen. They got to know each other in the narrow window of time when Glenn was breaking away from Corbett and Dunn, before his arrest. She has stood by him ever since. “I have been a wife to him as much as I could be to someone who is incarcerated,” she says.

That includes weathering the parole hearings. Gardner fled the room during Glenn’s 2017 hearing, frustrated by what she regards as a lack of fairness in the process. She did not attend the latest hearing. “I don’t see that there is anything he could do that would make a difference,” she says. “I feel like there’s a red stamp on his record that says ‘Never Parole.’ I feel like Kelsey Grammer’s weight on this is heavier than it should be.”

Glenn may have shifted his story for the board in hopes of telling them what they want to hear, but Gardner believes what he has always told her – that he didn’t kill Karen Grammer. It fits with the person she’s known for nearly five decades, the scared kid who didn’t know how to get out of a bad situation. The one who was represented by a personal injury lawyer in a capital case. The one who was convicted on the word of a co-defendant and was later advised to take the rap for something he didn’t do.

“Freddie is not a killer,” she says. “He’s not a butcher. He was a good young man who got caught up with some very bad people. He has helped a lot of people get parole. He can’t do it for himself, but he’s helped many people get out of prison over the past 47 years.”