Audio By Carbonatix

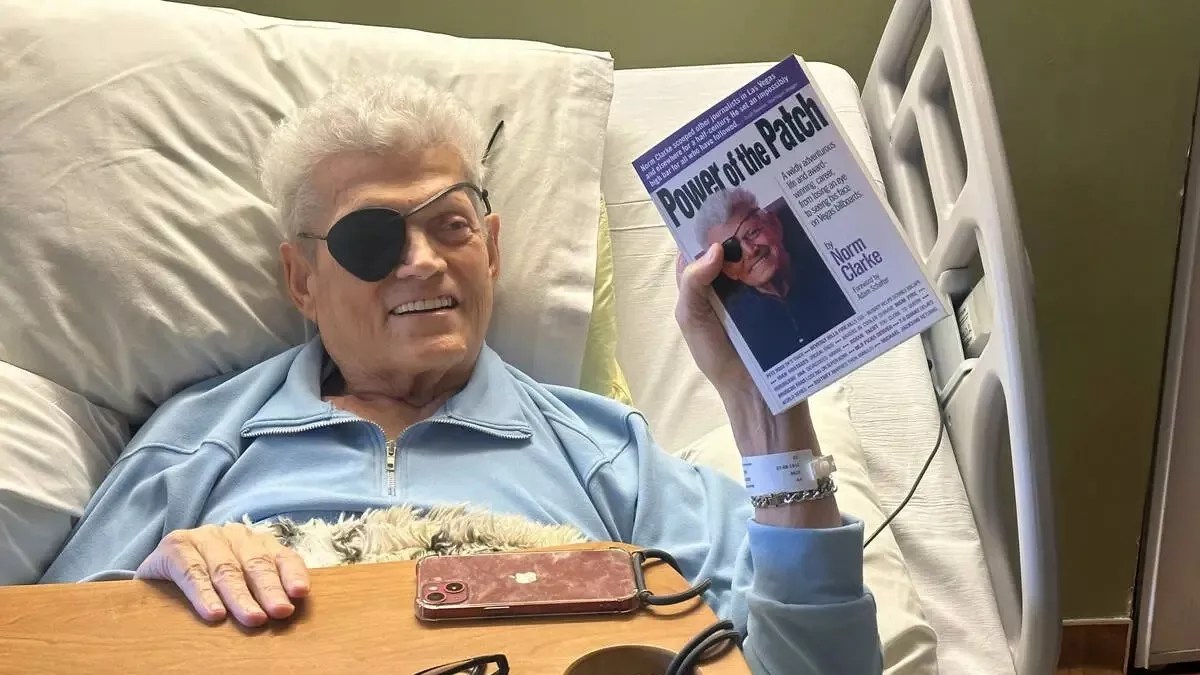

Norm Clarke, a journalist with a trademark eyepatch whose colorful career included a lengthy stint in Denver as a sportswriter and on-the-town columnist, died in Las Vegas on March 20. He was 82. But he lived long enough to see a copy of The Power of the Patch, a memoir that he spent the last eight years writing, detailing more than ten times that span filled with fun, frolic and much more than a dash of spice.

David McReynolds, who knew Clarke for more than forty years, partnered with him in publishing the tome and is honoring his friend’s wishes in regard to distributing it.

“The book is only available one way, and that’s for free,” McReynolds notes. “Anyone who writes our email address” – books@powerofthepatch.com – “will get the book for free. They just have to pay the shipping. The idea is to get it into as many people’s hands as possible – and we also plan on giving it to journalism schools. Norm’s hope was to inspire more people to go into journalism and have as wonderful a life as he did.”

Andrew Hudson, the namesake of Andrew Hudson’s Job List and another longtime Clarke pal, isn’t surprised by the giveaway, since he saw Clarke as an extremely generous soul. “One thing I’m finding from seeing stuff on social media and talking to different people about Norm is how many best friends he had,” he says.

Hudson was among the last people to see Clarke before his passing. Clarke had lived in Las Vegas since 1999, when he was lured away from his columnist gig at the now-defunct Rocky Mountain News by an offer from the Las Vegas Review-Journal. But Hudson reveals that Clarke, who’d been fighting cancer for nearly a quarter-century, was planning to relocate to an assisted living facility in Denver. Hudson had volunteered to stop by Vegas on the way back from a previously scheduled trip to San Diego to load some of Clarke’s belongings into his truck and carry them back to Colorado. But this plan was nixed after Clarke fell in his Las Vegas home and doctors discovered that his cancer had metastasized into his hip. Shortly thereafter, he was placed in hospice care, and Hudson visited him there. Hudson estimates that he left Clarke’s bedside at around 9:30 p.m. on March 19; Clarke passed away at 5:30 a.m. the next morning.

Days earlier, however, Clarke got a chance to hold a physical copy of his book, which he’d raced to complete even as his health was failing. Once Clarke wrapped up the tale, McReynolds gave its text to a printer who was able to assemble the package in just 24 hours – and Hudson thinks that once Clarke saw the final product, he knew it was time to let go.

“He was so excited to get it done,” Hudson says, “and after he got the book, he basically went to sleep and never woke up again.”

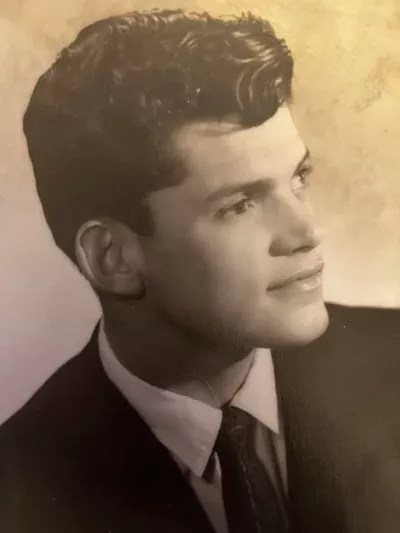

Norm Clarke’s 1960 high school graduation photo.

Courtesy of Andrew Hudson

As the Review-Journal‘s obituary makes clear, Clarke had plenty of obstacles to overcome. He was born in tiny Terry, Montana, in 1942, and during his childhood there, his eye was injured by a suspender that snapped loose. Several years later, the eye had turned “purplish-red,” the Review-Journal divulges, and a family doctor suggested that it be removed, in part because cancer ran in Clarke’s family. Hence, the eyepatch, which became his visual identifier.

“One of the themes of the book is how good things can come out of bad things,” McReynolds says. “His eye was taken out when he was ten, but that didn’t stop him. He had an amazing life.”

By his early teens, Clarke was delivering the local newspaper, the Miles City Star. He subsequently graduated to writing sports articles for the weekly Terry Tribune before shifting to the Helena Independent Record and the Billings Gazette, where he became a sportswriter.

The big leagues soon came calling: While still in his early twenties, Clarke was hired by the Associated Press and assigned to cover the Cincinnati Reds during their glorious Big Red Machine period; the squad won consecutive World Series in 1975 and 1976. Stints with the AP in San Diego and Los Angeles followed – but in 1984, he made the jump to the Rocky Mountain News. His biggest coup for the paper was breaking the news that Denver had landed a Major League Baseball expansion team, which became the Colorado Rockies.

In 1996, Clarke moved to the news department and starting writing what was often shorthanded as a gossip column – not that he ever would have used that term.

“He would say what he repeated wasn’t gossip,” Hudson points out, “because he would try his hardest to make sure it was true – which is a tribute to his journalistic skills. I can’t name a time when he got something wrong, but if he did, he was devastated, because he always wanted to get it right.”

Adds Hudson: “This was back in an era of journalism in Denver that doesn’t exist anymore. I remember picking up a Rocky Mountain News when my parents passed away, and even though it was, like, a Wednesday edition, it was 200 pages long, and they had a columnist for DIA, a religion columnist, a society columnist, a real estate columnist, a suburban columnist. There was just an insatiable desire from the public for that level of coverage.”

Clarke wasn’t alone in providing tidbits and chatter about the famous and infamous of Denver. Notable area columnists specializing in dish included Dick Kreck, Bill Husted, James Meadow and Penny Parker. Hudson, who worked in the public-relations field and served as a spokesperson for Denver Mayor Wellington Webb in the 1990s, recalls that the sense of competition between staffers at the Rocky and the Denver Post in that era was fierce.

“I’ve heard stories that if you were a reporter and you got scooped by the other paper, you had to walk through the newsroom and people would be booing and hissing you,” he says. “That’s how cutthroat it was. But that didn’t happen very often to Norm. He was Haley’s Comet. He was unique, he was different. His light just shined.”

That proved to be the case in Las Vegas as well. He was credited with plenty of in-print revelations at the Review-Journal – about, for instance, Britney Spears’s 2004 marriage, which lasted 55 hours, and Michael Jackson’s secret move to Sin City two years later. Along the way, he became nearly as big a star to denizens of the Strip as the luminaries he covered. Hudson recalls going to one show with Clarke, and during the curtain call, the entire cast donned eyepatches in tribute to him.

Norm Clarke with a copy of his memoir, The Power of the Patch, as seen in a photo taken days before his death.

Courtesy of Andrew Hudson

For the most part, Clarke’s readership didn’t know about his various medical issues. He was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2001, but managed to remain on the job at the Review-Journal until 2016 – and he subsequently returned to journalism via a news agency called Vegas Stats & Information Network.

After that gig ended, Clarke focused on his book and a website called Norm Clarke’s Vegas Diary. But he was able to spend more time with family and friends; he shared this past Christmas with Hudson’s family.

“He was just an amazing guy,” McReynolds says. “A totally kind, wonderful man whose memory was great right until the end. He was the type of guy who never met someone he didn’t know. If you were introduced to him at dinner, by the time you were finished eating, you were his friend. He was one of those guys.”

“God put him on this earth to be a journalist, because he was just so good at it,” Hudson adds. “The word that keeps coming to mind when I think about being his friend is ‘lucky.’ I just feel so lucky to have had someone like him in my life.”

Clarke’s survivors include his wife, Cara, brothers Jeff and Newell, and sister Nancy. Services are pending.