Erika Krouse

Audio By Carbonatix

You know all my tricks by now, but it doesn’t matter. Give me twenty minutes alone with you, and you’ll still tell me all your secrets.

This line is near the end of Colorado writer Erika Krouse‘s memoir, Tell Me Everything: The Story of a Private Investigation, but it’s also at the beginning, so quoting it is no spoiler. The sentiment is part and parcel of the entire work, as a matter of fact: This is a book that’s all about spilling the tea, Krouse’s included. And Colorado’s, too – specifically, the mess at the University of Colorado Boulder campus surrounding its gang-rape “recruiting scandal” of the early 2000s.

Colorado readers will recognize a lot from the book, which mentions things that only those accustomed to the rarefied air of mile-high elevation will understand: beetle-kill, Frozen Dead Guy Days, Blucifer and so on. But there are a few references that Krouse says she can’t officially confirm or deny. Actual names, specific events, updates on any of the book’s subjects, things like that. “You know: lawyers,” Krouse says.

And Krouse knows lawyers. Most of Tell Me Everything is about her work for one, dubbed Grayson, who pulled her out of a series of temp jobs to go work for him as a private investigator. Krouse was at this point a successful 33-year-old writer who was also – not coincidentally – working paycheck to paycheck to survive. “Everyone believes in this myth of the writer,” Krouse says. “I believed it, too.” She describes getting a book published as a “Hail Mary”: One shot, and if you make it to publication, you’re golden. People will line up at your door with fistfuls of money, asking you to write or read for them. But that doesn’t happen.

“I was destitute,” Krouse writes in Tell Me Everything. And “the year before, I’d had a short story published in the New Yorker. My collection of stories [Come Up and See Me Sometime] had come out with a major New York publisher. My book won a prize Toni Morrison had won ten years before.” Still, as the book opens in fall 2002, Krouse was doing data entry, and people were calling her “the new Linda.”

Names, again. Names are big in Tell Me Everything, not only because most have been changed, but also because they mean something. They carry power. The memoir may be a Colorado child through and through, but one that’s been cautiously clad in a windbreaker of altered nomenclature to protect both victim and perpetrator, parties both responsible and terrifyingly not so much. But if Krouse has done her due diligence – and she clearly has here – she’s also made it not so tough to connect the dots. Neither the name of the university nor the foothills town in which it sits are specified, but its landmarks – the Flatirons, the JonBenét Ramsey house, Chautauqua, Illegal Pete’s, etc. – all get name-dropped, just in case you forget what and where we’re talking about.

“The law is so gray,” Krouse says. “There’s not a yes or no about anything in terms of what I could use and what I couldn’t. It’s very random-feeling. We went through a legal review that was very long. Every word was examined. I wasn’t used to that. I was used to writing fiction.”

Flatiron Books

Still, she wanted to be careful not to re-victimize anyone. “One of my biggest concerns throughout was the privacy and the safety of the survivors. I didn’t want there to be any problems for them. They had too many when it was going on. Death threats and harassment,” Krouse recalls. “I realized there was a limit to how much I could keep them private, since this is such a public case. But one thing I’ve learned is that people can sometimes be outed by association. If I use a perpetrator’s name, there’s a chance some damage could splash back on the survivors or the town or the university, and so for those reasons, I left them out of the book. I wanted to make sure I was doing all I could do.”

Krouse admits that this gesture is largely just that; it’s not like so much was changed for the book that you can’t suss out the true identities of those involved. Especially readers who recall well all the media coverage of the case in Colorado some fifteen to twenty years ago.

So, no, Krouse may not have been able to name CU Coach Gary Barnett, but it’s simple enough to deduce that he’s Coach Wade Riggs, the man at the center of the recruiting part of the rape scandal, someone who didn’t necessarily invent the bad system but inherited it and rolled with it and blithely defended it to the bitter end. The unnamed female CU president is clearly Betsy Hoffman, who was not up to the unfortunate task of dealing with both the Barnett scandal and also Professor Ward Churchill’s muck-up of 9/11 commentary and Native American identity claims. Her Chaucer defense of the use of the term “cunt” as it was casually and cruelly applied to a female CU player was only one of the many reasons for her departure to less challenging pastures. That player is named Nina in the book, but is clearly kicker Katie Hnida, who notably broke barriers for women’s participation in sports only to be rewarded with abuse and the continued accusation of bringing the “Curse of Katie” down on the beleaguered Colorado Buffalo team in the years since. Perhaps most important is Simone, the pseudonym of the woman at the center of the case to which Krouse became connected, the case around which this book centers: a real-world survivor who heroically came forward and spoke out and fought like hell for what was right almost two decades before #MeToo.

These are names Colorado has heard before, but perhaps not for a while. It’s especially good to be reminded of the actions of Coach Barnett, who emerged from the conflagration largely unscathed. After supporting a system that abused women for the sake of attracting athletes. After dismissing Katie Hnida’s sexual assault and general abuse by offhandedly saying, “It was obvious Katie was not very good. She was awful. You know what guys do? They respect your ability. You can be ninety years old, but if you can go out and play, they’ll respect you. Katie was not only a girl, she was terrible. Okay? There’s no other way to say it.”

Barnett was temporarily suspended, apparently more for losing a string of games in spectacular fashion (the book recalls one game that the Buffs lost 70-3) than for any action on his part, and was eventually bought out of his contract in 2005. In 2019, he was inducted into the CU Athletic Hall of Fame, and Tell Me Everything points out that he “forgave everyone that had wronged him while he was a coach.”

Big of him. But really, it was obvious that Coach Barnett was not a very good person. He was awful. You know what people do? They pay attention to what you do and what you say. Barnett was not only a misogynist, he was terrible. Okay? There’s no other way to say it.

Imitation isn’t flattery – it’s protection…tear a mimic free from her disguise and you’ll find only inner flesh, viscera, a heart emptying its last blood into the dirt. She will die, and be eaten. Unless she learns how to rip off your disguise first.

There’s something about Krouse’s face that she thinks makes people open up in ways they don’t intend, can’t even really help, to unleash their secrets, their past, their worries, their dreams – all of the things that we do to hide behind the false visage of fine-ness that we want to project to the world. “Something in my face,” she writes in Tell Me Everything, “bore the shape of a key, or a steel table on which to lay something heavy.” Krouse talks a lot about her face and her history in her memoir, how both have been broken in different ways, how both bring her to this space in which she went from successful writer to private investigator and became embroiled, gumshoe-style, in a case about rape and the systemic abuse of women in college football.

It’s not just the friendly geography of her face. “During this period of masking, people have still opened up to me, even though half my face was covered,” Krouse says. “But there’s a longing that most people have to be seen and understood and heard. For most people, their face is like a mask that pushes away; some of us have the opposite. The sort of face that absorbs.”

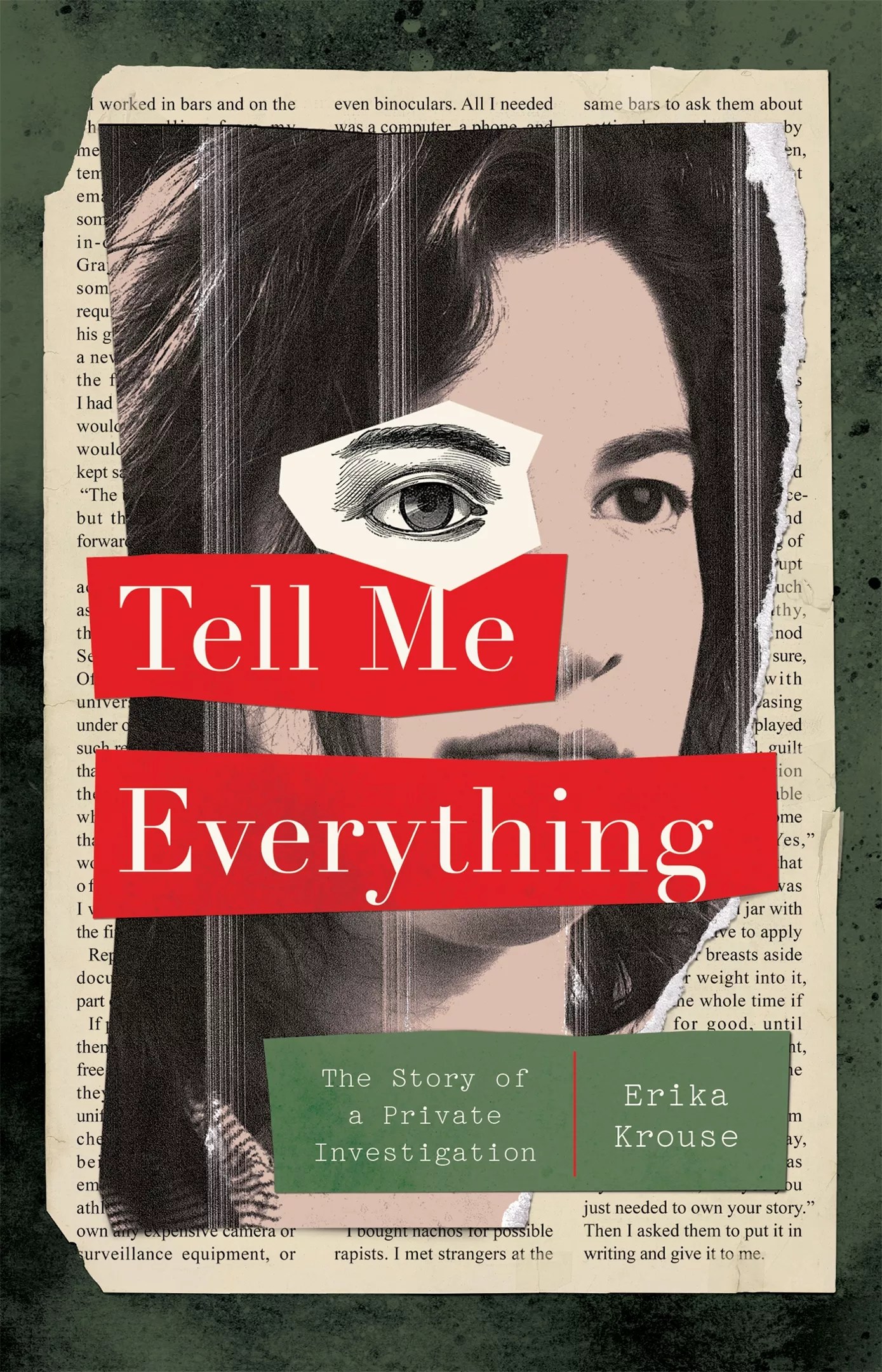

For a book that’s so much about faces, it’s notable that Tell Me Everything‘s book jacket is peculiarly absent of any traditional author photo. But it’s there nonetheless: The graphic on the cover is actually based on a photo of Krouse, taken back in the early 2000s, sometime around the same time as the attack that she’d later spend so many years with, working to help bring justice. It makes some sense that she’d be a part of the cover of a book in which her own trauma is also such an integral part.

How did Krouse come up with the idea of dovetailing her own personal history of abuse with this much larger and more public example? “I didn’t want to,” Krouse says, and laughs. “I wanted to write about the case. These exceptionally brave women. They wanted to change things, and were willing to risk their own safety and their own sanity to change things for everyone else. Things weren’t going to change for them; the worst had already happened to them. So they were doing this incredibly altruistic thing. For me to hide and pretend like this was a completely external thing and had nothing to do with my life or my experiences, that would have been really cowardly.”

Not that it was easy to do. “I thought about writing this book for a long time. I wrote a few drafts of the proposal,” Krouse recalls, “and my agent kept kicking it back to me and saying, ‘You know, if you’re going to write a memoir, you kind of have to be in the book.’ So finally I decided there was no way around it. I had to jump in with both feet.”

In developing the book, Krouse encountered some pushback, everything from complaints to outright bullying that she chooses not to detail. “But it made me consider the greater good,” she says. “I had to decide it was a better thing to make a couple of people feel bad about their misdeeds while showcasing this lawsuit that made all of us safer, that really changed law.”

What Nietzsche didn’t mention is how easy it is for the abyss to disguise itself.

Krouse doesn’t do private investigation work anymore. “I was trying to figure out who I was in that job,” she says. “I became something that when I looked into the mirror, I didn’t like.” In the book, she writes that she’d become “a manipulator, a liar, an information thief, an agoraphobe, an intruder, a panic-ridden insomniac, a depressive, an exploiter, an avenger, and nearly a suicide…I’ve never been able to reconcile the two realities – the good I did versus the person I became to do it.”

So Krouse un-became that person, or at least works at it. She hung up her metaphoric fedora on her equally metaphoric hat rack in the noir office with the stenciled, glass-windowed door that she never had. “I love that idea that a writer can just choose to go back to writing, like that’s a thing,” Krouse says, and laughs. “Let’s just dispel that right away.” But she talks about teaching at Lighthouse Writers Workshop, and loving that, and editing for other writers, which she says fills much of her time very happily. She also has the back half of her two-book deal to fulfill, another short story collection, and a novel planned beyond that. “My immediate future looks a lot like my recent past,” she says. “I feel fortunate to have a professional life that I finally love.”

In the end, Krouse’s Tell Me Everything is a beautiful piece of prose about some very ugly things. It’s reflective and incisive in all the right ways, the ways you’d want them to be were you at a bar sharing some appetizers and drinking a couple of beers with an acquaintance to whom you’re spilling your guts just because she has that kind of face. And it sheds light on a lot of issues in national academia and the superstructure of college sports and the culture of sexual assault that too often go hand in hand with both.

If you doubt that relationship, doubt that it’s still continuing today, doubt that this book is relevant in 2023? All you need to consider is this: The story contained within is nonfiction. It’s history, provable and immutable, and it’s about rape, about the violent sexual assault of women and the system that protected and perpetuated it. But if you research it, most people – not all, and certainly not Erika Krouse – still just refer to it as the “Colorado Recruiting Scandal.”

Why? That’s something America needs to ask, something we need to collectively face, the central question Erika Krouse is posing. It’s okay. You can tell me. We’re just talking here.

Erika Krouse’s Tell Me Everything just won the 2023 Colorado Book Award in creative nonfiction; this story was originally published in March 2022.