Tahvory Bunting@Denver Image Photography

Audio By Carbonatix

Erin Parisi walks with purpose – and she has one. Parisi is over halfway to becoming the first openly transgender athlete to climb to the highest point on all seven continents, a feat called the Seven Summits that was pioneered by Dick Bass in 1985. She’s already summited Africa’s Mount Kilimanjaro, Australia’s Mount Kosciuszko, Europe’s Mount Elbrus and South America’s Mount Aconcagua.

Parisi sets a steady pace up the trail to Pass Creek Lake, which is nestled in the mountains of the San Isabel National Forest near Salida. A neon-green Sweet Cow baseball cap is strapped atop her 85-liter Osprey pack. Despite the trail’s steep grade, she refuses to set down her pack and pauses only briefly to catch her breath.

If all had gone as planned, Parisi would be ascending to far greater heights this summer. Her original itinerary called for climbing Alaska’s famed Mount Denali, the highest mountain in North America, with a summit elevation of 20,310 feet. The trip, which wound up being postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, had been scheduled for June, to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the first Pride march, on June 28, 1970.

Although her plans are on pause, Parisi remains committed to conquering the highest peaks on each continent.

“I never thought I would try to climb the Seven Summits,” she admits. “I’d climbed Kilimanjaro for fun shortly before I transitioned, but I never had my eyes set on these big mountains. You know, I’m happy just being outdoors. These big mountains are very much a different thing for me, and the reason I’m climbing them is very much for the trans community. We need to see trans people proud of who they are and willing to be seen.

“These mountains are metaphorically where the world can’t push you into the shadows anymore. You’re standing on the highest points of the world saying, ‘I’m not hiding.'”

Despite this summer’s setbacks, Parisi is still climbing. This backpacking trip isn’t purely recreational: Parisi is already training for 2021. She has her sights set on the highest peak in the world, Mount Everest, which juts 29,035 feet into the Himalayan sky.

Erin Parisi at Pass Creek Lake near Salida.

Sage Marshall

Parisi grew up in Clarence, New York, a suburb of Buffalo that she describes as the epitome of “picket-fence suburbia.” It was a place that Parisi, who has three brothers and one sister, long sought to leave. The only vacations the family took were road trips to camping areas in the Alleghenies, where Parisi was able to run free, explore the woods and jump in lakes.

She struggled with her gender identity from a young age. The only trans person she knew was a member of the Protestant church that her family attended. Peggy was an older woman who had transitioned later in life. “The cool high school kids had a tradition of egging her house every year on Labor Day. It was really nasty,” remembers Parisi, who’s now 43. “I always just kind of disappeared.”

High school was an especially difficult time for Parisi, who recalls a blur of drugs and alcohol. She played defensive end and fullback on her high school football team. Her teammates were unaware of her true identity – and gave her reason to wonder if she might have to live in the closet her whole life. “I was in the locker room, playing football with the guys, and I heard the talk,” she recalls. “I heard how funny it was if somebody was a trans person. I heard the jokes about ‘pulling up your dress or panties.'”

Contemporary culture was rife with stereotypes. For instance, Ace Ventura: Pet Detective had a decidedly anti-trans message. “Ace Ventura taught me that if I was seen and somebody made physical contact with me, everyone in the room would puke,” she says, referring to a scene where a transgender character is forced to expose herself to a room full of cops, and every one of them who’d kissed her without knowing she was trans begins to vomit.

Parisi also cringed at Silence of the Lambs, which won eight Academy Awards in 1992. The main plot of the horror film revolves around a character named “Buffalo Bill,” who murders women in an attempt to wear their skin.

Parisi’s Aunt Beth, a member of the LGBTQ+ community, was a role model. She watched out for Parisi early on and played a significant role in developing her love for the outdoors. Beth lived in Santa Fe and took her niece to the Rocky Mountains of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado, where the two of them skied, hiked and enjoyed nature; she also took her to Canada for similar adventures. Besides simply inspiring Parisi to get outside, Beth showed her something far more important – that the outdoors could serve as a valuable outlet for self-meditation and healing.

After attending the State University of New York at Buffalo, where she studied business and economics, Parisi knew she had to get away.

“There was a narrative from when I was a kid that once people transitioned, they move away, cut ties and start over,” she explains. “The idea was just to blend in and not be seen, heard or talked about at all. You can’t do that if you’re keeping ties to your family.

“Look at the nameless graves in New York City, where they’ve been burying homeless victims of COVID,” she continues. “They’re buried alongside people whose families rejected them and didn’t take them back after they died in the AIDs epidemic. Their families said, ‘Not only in life, but in death, we don’t want you back.'”

“These mountains are metaphorically where the world can’t push you into the shadows anymore.”

Denver seemed to have all the goods: It was a bigger city, had resources and health care for trans people, an established LGBTQ+ community and, of course, a close proximity to the Rocky Mountains. Parisi moved to Colorado in 2002.

Her Aunt Beth joined her in exploring her new home, while also making sure that she knew what she was doing in the backcountry. She signed Parisi up for her first avalanche safety class.

Parisi tried a hodgepodge of outdoor activities, from water sports like kayaking to skiing. While her interest in some sports fell off, she developed lasting passions for mountaineering, mountain biking and backcountry skiing – all pursuits that allowed her to explore the mountains she’d fallen for.

“What I like about mountains is the variation you see going from the base to the summit,” she says, noting that you can explore a variety of ecosystems, from the desert to high-alpine tundra, in a matter of hours. “The more you explore, the more you realize the differences as you cross one ecosystem to another.”

As she tackled more and more local peaks, Parisi’s gaze drifted toward more distant horizons. Since she hadn’t traveled much as a child, one of the things that especially appealed to her about mountaineering was that it allowed her to experience unfamiliar landscapes and cultures.

“You can do two things in the mountains, which are really cool,” says Parisi. “You can escape and let your thoughts run, and you can build friendships that are bigger than friendships.”

But there’s also something intangible about Parisi’s love of the outdoors. “It’s like strawberries,” she explains. “It’s hard to say exactly why you like them so much – you just do.”

Erin Parisi on Mount Aconcagua.

Manuel DiLenardo

Although Parisi was already considering transitioning when she moved to Denver, she continued living in the closet for twelve years. Her friends were unaware of her identity, and she witnessed the unfiltered attitudes some had about transgender people.

“You’re on a golf course with four guys, and all they talk about, I swear, is how one man resembles a woman,” she says. “I was one of the four. What does that do to me, listening to that kind of language? It makes me not want to be seen.

“I was always afraid of who I was,” she adds. “I had the American dream, but it just wasn’t me. It wasn’t my narrative. Ultimately, you can’t run from yourself.”

One of the reasons Parisi was able to reach this conclusion was the countless hours she spent on the trail and skiing in the backcountry, where she had time and space for introspection. But the outdoors is also a highly gendered space, and Parisi was uncomfortable with the gender dynamics she’d encountered from her first day at summer camp to the last day she was climbing at a local crag before transitioning.

When Parisi finally decided to come out six years ago, she spent two months traveling the United States looking for another place to relocate – one where people wouldn’t know her history. She considered moving to a bigger city, even New York.

But she couldn’t stomach leaving the place that had become home, especially because it would mean giving up the mountains.

“I just said, ‘You know what? Fuck that. If I’ve got to relocate, I’ve got to relocate. But I’m coming out in Denver,'” recalls Parisi. “One by one, as I came out to people, they were accepting and started recognizing my pronouns.”

Still, Parisi faced setbacks.

Cory Weeks is happy for his cousin.

Courtesy Cory Weeks

“People would see you, especially in the smaller suburbs of Denver, and they would pull their kids away from you or something,” she says. “It hits you right in the heart.”

During her transition, Parisi initially tried to “run from one closet into the other,” she says, going from looking like a man to looking like a woman with as little time in between as possible. She’s all for gender fluidity and supports people’s right to express their gender and sexuality however they desire. But for her – and often for other trans people her age – “the narrative is to not be seen and not be heard.”

In her day-to-day life, Parisi doesn’t tell people she’s trans. She works as a portfolio manager for a telecommunications company and manages its real estate assets in rural areas, where her “safety depends on being able to come and go unnoticed, without giving up too much information,” she says.

Parisi had been married, but the marriage fell apart during her transition.

To come out to her father, Parisi flew to California, where he now lives. The day she planned on telling him her true identity, he got into an argument with her about gay marriage. Parisi hesitated and waited until the next day, when she came out just before getting on her flight home.

The minute she landed at Denver International Airport, she got a call from her father, who told her he accepted her and supported her for who she was. Parisi also received a better-than-expected response from most of the other family members she talked with.

“I ended up being the one who was wrong. I implied to my family that they wouldn’t accept me. That’s what I thought of their level of tolerance, and I missed the mark,” she says.

“When Erin came out, everyone was surprised. My immediate reaction was just feeling sad that she had to carry that around with her for so long,” remembers Cory Weeks, a cousin who identifies as gay. “I was also really happy and relieved for her to take that step. For me and most of my wider family, Erin was the first trans person we knew well.”

But Parisi’s challenges weren’t over.

Erin Parisi at Low Camp on Mount Aconcagua.

Manuel DiLenardo

Mountaineering while trans brings a whole new set of obstacles to an already intensely challenging activity. On her best day, Parisi is seen as a solo female traveler; on her worst, she’s regarded negatively as a trans female traveler.

In February 2018, Parisi went on her first real mountaineering trip after transitioning. She targeted the summit of 7,319-foot Mount Kosciuszko in the Snowy Mountains of Australia, a place she considered to be fairly socially progressive. The trip was a huge success. Parisi notched the first of her Seven Summits after coming out as trans, boosting her confidence in her ability to continue. “It was everything I needed,” she says. “It was an escape from my divorce and the first time I had my new passport – and it was working. The whole thing was amazing.”

Stoked by that success, Parisi planned to head to Tanzania several weeks later, to again climb the 19,340-foot Mount Kilimanjaro – this time presenting as a woman. Back in Denver in the interim, disaster struck. She went to a taco shop near her house and left her beloved dog outside. While she was inside, a group of strangers took her dog and put it in their car, then began berating Parisi when she returned for leaving her dog – which had often joined her climbing fourteeners – in the cold. Parisi’s dead name, the term for the name a transgender person used before they transitioned, was still on her dog’s collar. One of the strangers made the connection.

“These drunk college guys started attacking me for being trans and going into how shitty my life is and how terrible I’m treating my dog. They argued I didn’t have any self-worth as a trans person, but with uglier words,” she recalls.

They then started beating her up. Parisi ran home as fast as she could and immediately called the police and the taco shop. But by then, the offenders had fled, and the authorities were unable to locate them. No charges could be filed.

The experience shook Parisi and increased her anxiety about her upcoming trip. Tanzania has barbaric laws concerning the LGBTQ+ community, which Human Rights Watch has repeatedly decried. Moreover, Parisi was planning to climb with guides she’d used on the same climb years before, when she still presented as a man.

She wound up telling the guides that the man – her past self – who’d referred her to them was her cousin. She was startled when they remembered an old nickname they’d used for her on the original trip.

“It’s almost counterintuitive,” she says. “Here I am wanting to stand on the highest mountains and tell the world I’m not afraid to be who I am, and then I go to places like Tanzania and realize it’s still not a possibility.”

Still, Parisi had her sights set on climbing out of the shadows, even if it meant going to a place marked by intolerance toward members of the LGBTQ+ community. She boarded the flight to Tanzania two days after being attacked minutes from her home.

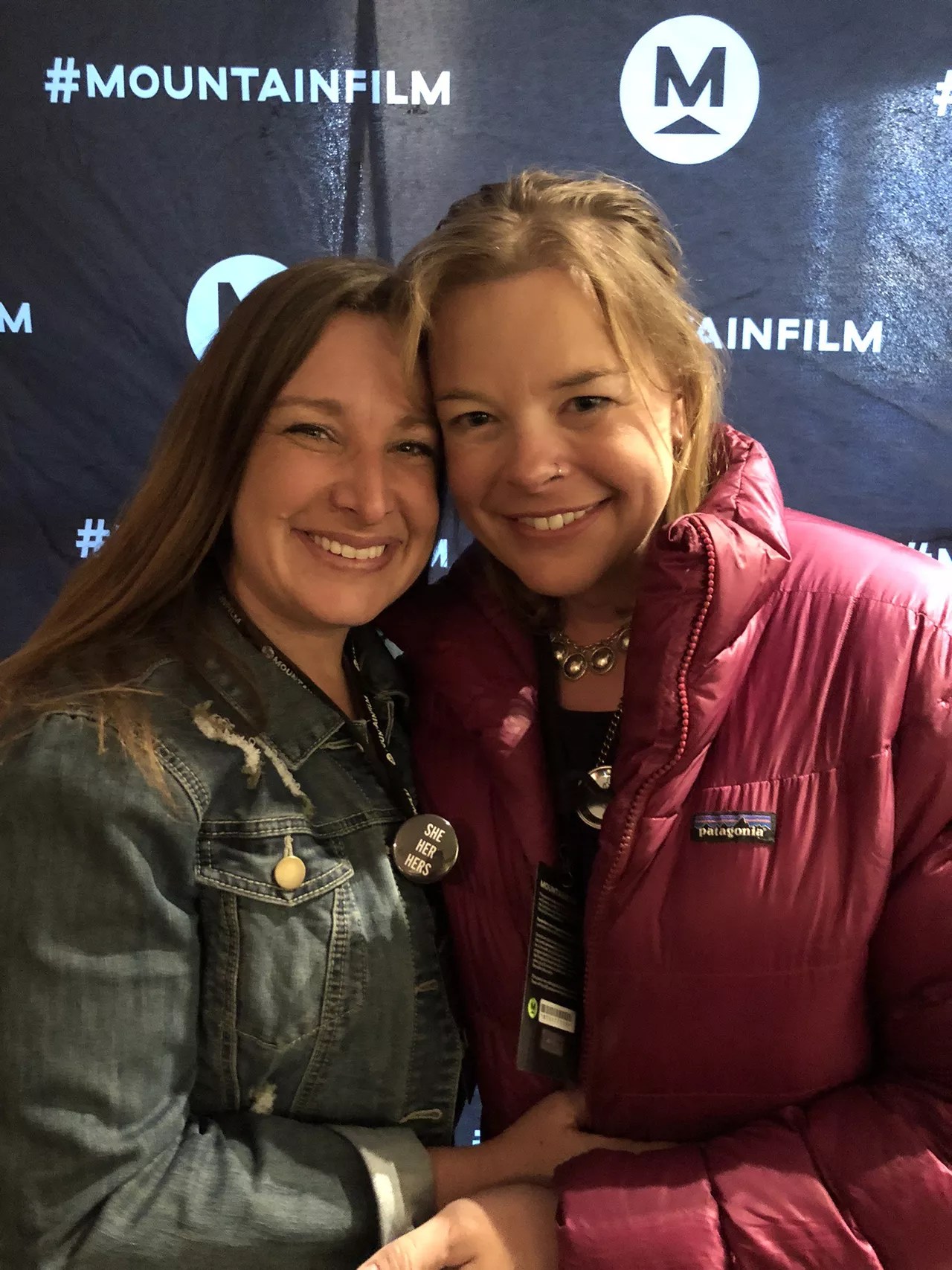

Erin Parisi and her partner, Allison, who is also on the TranSending board.

Brianna TItone

“There was a time when it was kind of like a ‘fuck you’ to the world,” says Parisi of the start of her quest to climb the Seven Summits. “It was like, you don’t want to see me and don’t want to hear from me, but the more I climbed and the more support I got from cis and trans people around the world, the more I realize I’m doing this for and with a community.”

In April 2018, Parisi decided to further support that community by founding TranSending 7, a nonprofit “dedicated to the advancement of transgender rights throughout all aspects of society by promoting athletics as a platform of transgender awareness and inclusion.”

A lot of the discussion about trans rights in sports has centered on team sports, she notes, and there hasn’t been a broader discussion about trans inclusion in outdoor sports. TranSending 7’s inaugural goal is to see Parisi to the tops of the highest peaks on each continent – but its mission doesn’t end there.

“I want to spark a discussion around outdoor sports. We need visibility,” Parisi says. “What would it take for a trans person to sail around the world solo or climb the Dawn Wall?”

“We need somebody to stand on the highest place in the world and say, ‘Here I am.’”

Although TranSending 7 has yet to find other trans athletes to sponsor, the nonprofit’s board is already packed with local trans advocates. Emma Shinn, the chairperson of the board, is one of the few openly trans Marines; she’s supported Parisi and her nonprofit from the start. In July, state lawmaker Brianna Titone became TranSending 7’s newest boardmember. When she was elected as a state representative in 2018, Titone became Colorado’s first transgender legislator. An Arvada resident, she was following in the footsteps of Joanne Conte, a transgender Arvada City Council member in the early ’90s who was the subject of a Westword cover story.

Before being elected, Titone told Westword, “Times are really changing, and I think that this is the time where people are seeing that marginalized people are productive members of society. We’re no different than anybody else. Our identity really doesn’t matter; we just want to be productive members of society and help make the place better. We exist.”

The third boardmember is Allison, Parisi’s current partner (the couple asked that her full name be withheld over concerns for the family’s safety). Allison and Parisi are parents to eight-year-old Alyx, whom Parisi is looking forward to taking on her first backpacking trip.

“I’m a cis white chick. I didn’t know anything about trans people or know anyone who was trans before I met Erin,” says Allison, who manages communications for TranSending 7.

“The media has a habit of celebrating trans lives when we’re killed,” says Parisi. “We don’t tend to celebrate stories of living trans people. Families, friends and support networks need to see that happening instead of death, homelessness, shame and stigma.”

In addition to TranSending 7, Parisi works with other nonprofits such as Venture Out Project, an organization that works to make the outdoors accessible for LGBTQ+ youth. Parisi has also become heavily involved with the American Alpine Club, the nation’s foremost climbing and mountaineering organization. “I believe nature should be an even playing field for all,” says Heidi McDowell, AAC’s events director. “The reality is that it’s not. The outdoor industry at large has had on rose-colored glasses about this truth.

“A big part of rectifying this is uplifting the voices and stories of people like Parisi who are doing incredible, cutting-edge things. Summiting the Seven Summits is a huge marker of achievement for anybody in the climbing industry,” she continues. “Parisi’s attempt to be the first transgender athlete to do so really sets an example for others who may have been feeling marginalized to look up to and say, ‘Oh, there’s somebody like me who’s doing this incredible thing. Maybe I can get outside and go climbing, too.'”

Representative Brianna Titone is on the board of TranSending 7.

Brianna Titone

Despite relentless rain and casual sexism from her guides, who thankfully didn’t connect the dots to her prior identity, Parisi successfully summited Kilimanjaro on March 8, 2018 – International Women’s Day. That June, she went on to summit Mount Elbrus in the Chechnya region of Russia, another area known for its intolerance and persecution of queer and trans people.

On her next trip, Parisi took a trans flag to the top of Argentina’s Aconcagua, the highest peak in South America – and anywhere outside of the Himalayas.

“When you start climbing high, you start really challenging yourself and realize how strong you are or aren’t,” says Parisi. “The reason I continue to mountaineer now is very much because I thought I would lose it.”

There is no more infamous challenge than Mount Everest, which was first summited by Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hillary in 1953. Their group included Jan Morris, the expedition’s media runner, when she still presented as a man. Embedded with the team, she climbed 17,900 feet to a base camp. While she didn’t attempt to summit the mountain, she played a pivotal role as the journalist who relayed the news of Norgay and Hillary’s success to the rest of the world.

In Parisi’s eyes, Everest has had a trans history from the beginning, even if it’s one that’s little acknowledged.

Morris transitioned nineteen years after the expedition and went on to become a well-known writer. “It altered my life so much,” Morris said of the Everest trip in a recent New York Times feature. “And now I’m the only surviving member of the expedition, and I miss them all.”

Since that initial ascent, over 4,000 people have reached the very top of the highest peak in the world – but none of them have been openly transgender. Parisi seeks to change that.

“I’m sad that it hasn’t been done before,” she says. “We need somebody to do it. We need somebody to stand on the highest place in the world and say, ‘Here I am.'”

TranSending 7 is in the midst of a fundraising push that would give Parisi the financial resources to make this dream a reality. But the COVID-19 pandemic has brought added complications, and next year’s climbing season is still up in the air. But if anyone can climb Everest in 2021, Parisi wants to be that person.

“I think the world is ready to feel those stories of recovery, resilience and healing,” she says, “and 2021 is hopefully going to be about that.”

“I came out, and in a lot of ways, I freed myself when I did.”

In the meantime, she’s continuing to take treks – and take them seriously. While the trip to Pass Creek Lake is relatively insignificant, Parisi still pays close attention to planning and execution. She arrives at the trailhead with photos of the trail from AllTrails and a bulky Garmin Inreach satellite communicator. Beyond those, she’s packed only the barest of necessities, which include a compact bag of ready-to-eat food and an Outdoor Research bivy, a type of minimalist shelter that Parisi describes as akin to sleeping in a big trash bag.

“One thing in our daily lives that’s impacted by her mountaineering background is her ability to risk-assess and plan ahead,” Allison says of her partner. “That carries over to every aspect of our lives. Erin is risk-averse. She’s not willing to put herself or her loved ones in harm’s way for any reason.”

In the run-up to a big climb, Parisi usually completes several high-interval workouts at Orangetheory Fitness every day and trains at a local climbing gym. She supplements these workouts with functional training in the field – hiking and mountain biking. She prefers the less-traveled trails, she says, and has an affinity for the wilderness experience.

If she doesn’t have time to make it to the mountains, she’ll load her backpack with weight and climb the stairs at Red Rocks Amphitheatre.

Erin Parisi hiking on Pass Creek Trail.

Sage Marshall

The topography of the Seven Summits is etched across Parisi’s body; the coordinates of each of the four summits she’s accomplished are tattooed on the corresponding parts of her body. On one of her calves is the tattoo of a birdcage, but the birds are standing outside of it, alongside colorful flowers. Across her back is the striking image of a battle-weary knight in shining armor. The knight is a woman.

“I came out, and in a lot of ways, I freed myself when I did,” Parisi says.

While the San Isabel National Forest is in Colorado, Mount Everest doesn’t seem so far away. Parisi is usually upbeat, cheerful and quick to smile, even on the hardest parts of the Pass Creek Trail. But when she talks about Everest, her tone shifts, displaying the deep passion and focus that has made her a world-class mountaineer. She’s nervous about the altitude of Everest, a mountain that is littered with the corpses of some of the more than 300 people who’ve died on the way to the summit, but she’s determined to finish her mission.

“In my life, climbing these mountains is about resilience,” Parisi says. “I was beaten down and lost some things in my life, but still, I kept climbing.

“What’s important to me is bringing what’s on the inside out. That’s what I’m trying to do here. You shouldn’t be afraid to own your story and write your narrative. You should write the story that you have inside of you, not the narrative you think the world wants you to live.”

Parisi continues to write her story – not only with her advocacy, but with her actions, as she climbs the tallest mountains in the world.

“I love reaching the summit,” she says. “You suffer on a lot on those big mountains – any summit, even. Then you hit that top point, and you’ve pushed yourself through it. You’re exhausted, and you’re still only halfway there, but you hit the high point. It’s euphoric. To get yourself there, you almost have to put yourself in a trance to push through so much pain, but then it all goes away when you’re up there celebrating with your crew.”