Jim Sears

Audio By Carbonatix

It’s a long journey to get to outer space, but Boulder scientist Jim Sears is now one step closer to realizing his dream of seeing his space-ready oven cooking away on the International Space Station. In August, his SATED (safe appliance, tidy, efficient and delicious) oven was named runner-up in the final phase of NASA’s Deep Space Food Challenge.

We’ve been covering Sears and his SATED oven’s space journey for over a year. As one of NASA’s Centennial Challenges, the Deep Space Food Challenge encourages the invention of food technologies that will help feed people in multi-year deep space exploration and extraplanetary habitation. Past participants included companies that built autonomous self-sustaining greenhouses, developed edible mushroom proteins and demonstrated how carbon dioxide could be converted into alcohol to feed edible yeast to make proteins, fats and carbohydrates.

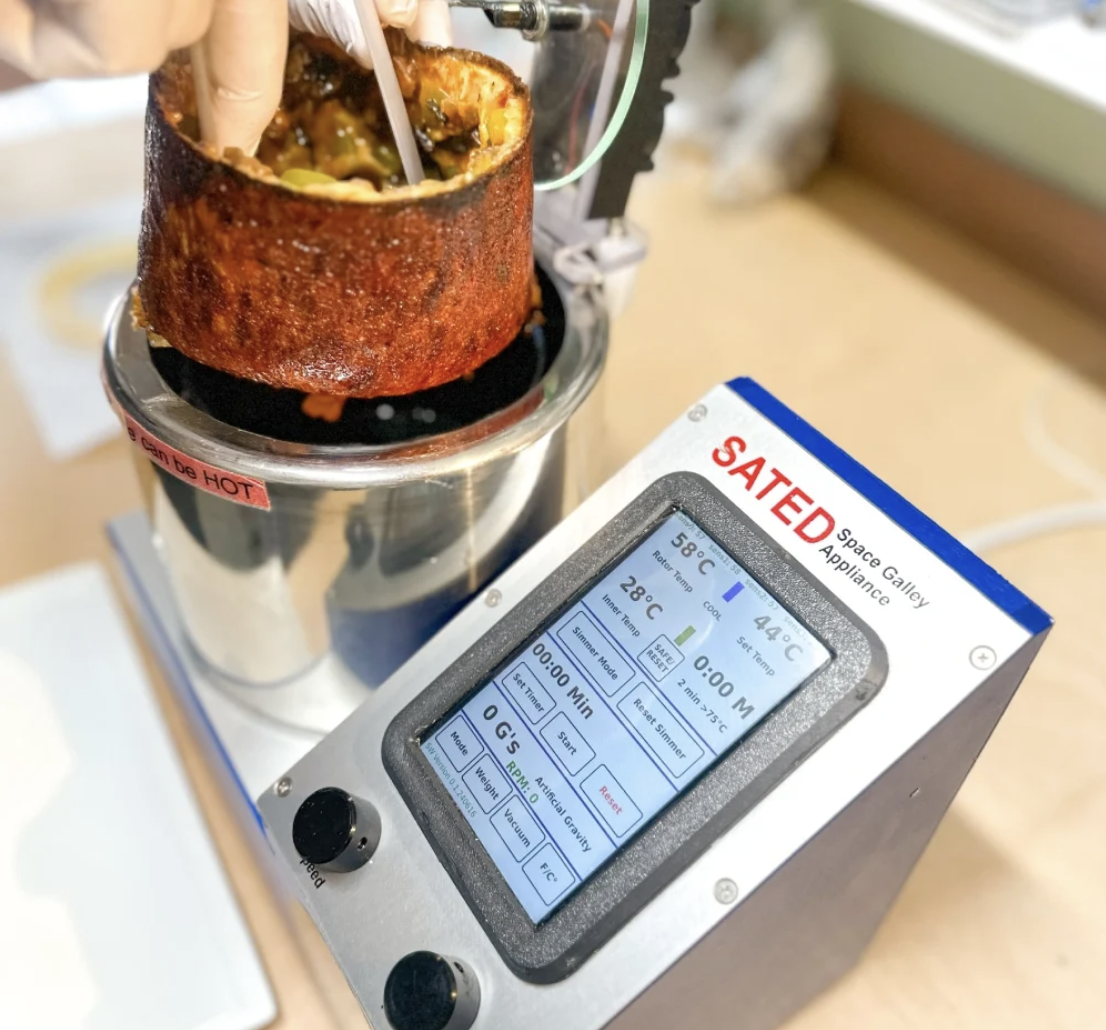

SATED, Sears’s one-man company, was the only entry that tackled cooking in space – a tricky problem considering that astronauts operate in highly flammable environments constrained in tight spaces with little to no gravity. The SATED oven cooks food in a spinning cylinder, creating its own artificial gravity through centrifugal force, which pushes the food up against walls heated by ceramic heaters. The technology is groundbreaking, and SATED was chosen as one of eleven Phase 2 finalists that could participate in the last and final Phase 3.

Phase 2 judges evaluated the technologies in controlled laboratory environments; Phase 3 is about real-world testing. NASA partnered with Ohio State University to recruit undergraduate student “Simunauts” to simulate the ISS crew working inside a Pilot Plant, which was “built to simulate what a research facility would look and operate like in a deep space environment,” according to NASA.

Jim Sears, center, on stage accepting the runner-up award with his family.

Jim Sears

There were only a few months to prepare for Phase 3, so Sears focused his time on refining the oven to its next logical iteration. That included upgrading the analog interface to a digital display, making the oven slightly larger, swapping out custom parts for professionally machined components, improving its watertight seal and adding a simmer mode. In mid-June, he packed his bags and two of his SATED ovens and flew to Columbus, Ohio.

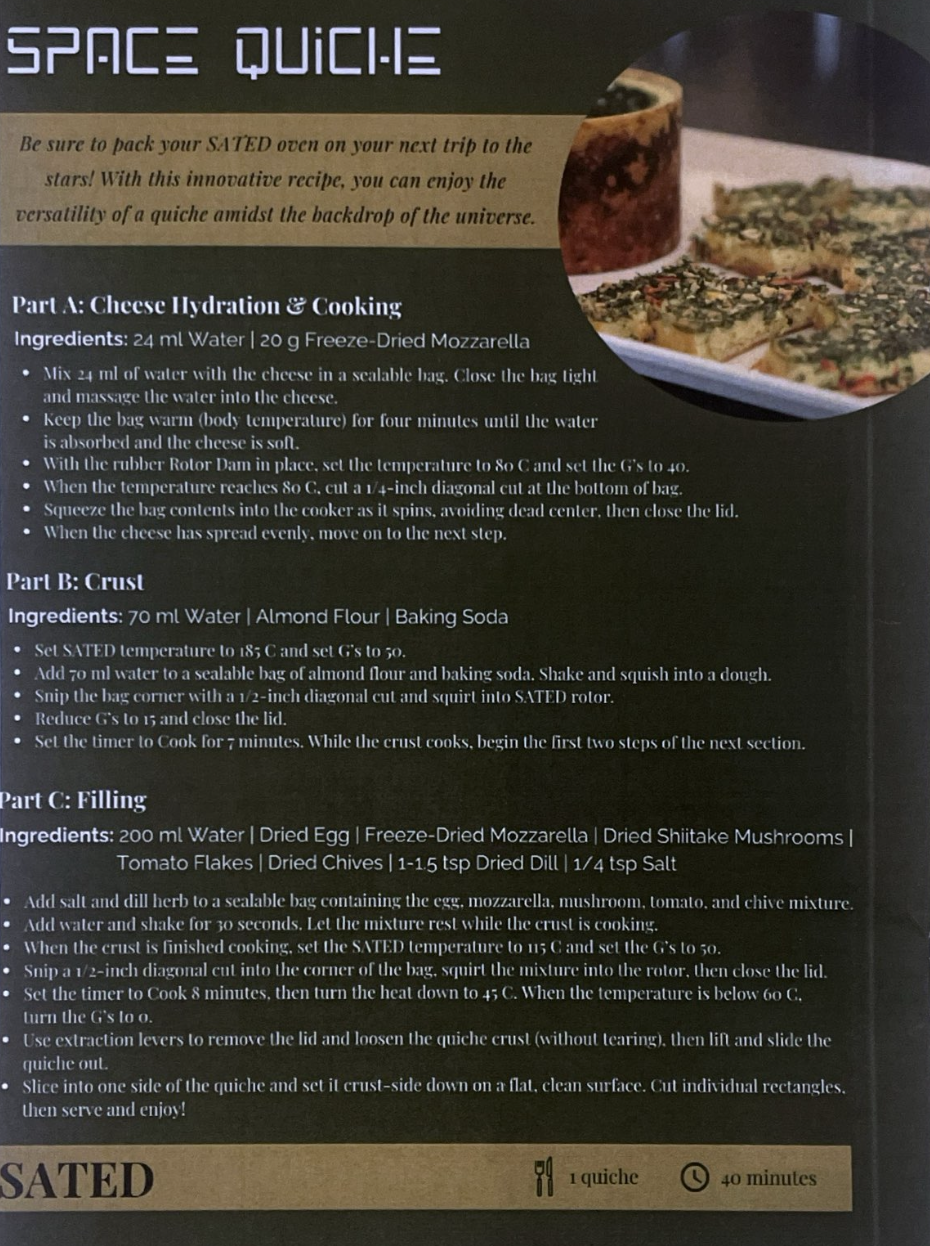

He was given two days to debrief and train his Simunauts. He gave them a one-page recipe for his space quiche, an almond-crusted quiche with freeze-dried mozzarella, shiitake mushrooms, tomatoes, chives and dill. It reads a little differently than a normal cookbook recipe, with instructions to “set the temperature to 80 C and set the G’s to 40. … Squeeze the bag contents into the cooker as it spins, avoiding the dead center, then close the lid.”

The idea was that “someone who has never touched the machine could read these test procedures and learn how to operate the machine,” explains Sears. “So I went, trained them on the test procedure, and then I had to go home.” He continued to provide remote troubleshooting and technical support for his crew, just like Mission Control would in real life. On July 15 and 16, the four-person Simunaut crew made space quiche for a panel of fifty taste-testers who graded aroma, mouthfeel, taste, etc., on a hedonic scale from one to nine.

“I thought it was great! But some of the taste-testers thought it was a big meh. … I think they must be used to tasting some really good gourmet food,” laughs Sears. But he had one big fan: ISS director Robyn Gatens. “She was eating the quiche during safety testing when I wasn’t there and reportedly said, ‘This quiche is delicious!’ She also told me the same when we later met at the symposium.

The recipe for Space Quiche.

Jim Sears

“The space pizza is better than the quiche,” he notes. But there were technical reasons for choosing the quiche: Space pizza is slightly harder to cook, and there was a possibility the wheat flour wouldn’t have passed the microbial testing requirements.

In addition to taste, Phase 3 participants were evaluated on “acceptability and safety of the production process and resulting food, inputs/outputs in relation to quantity of food produced, nutritional quality and water use, reliability of the food production technology, and stability of the input products and food outputs,” according to NASA.

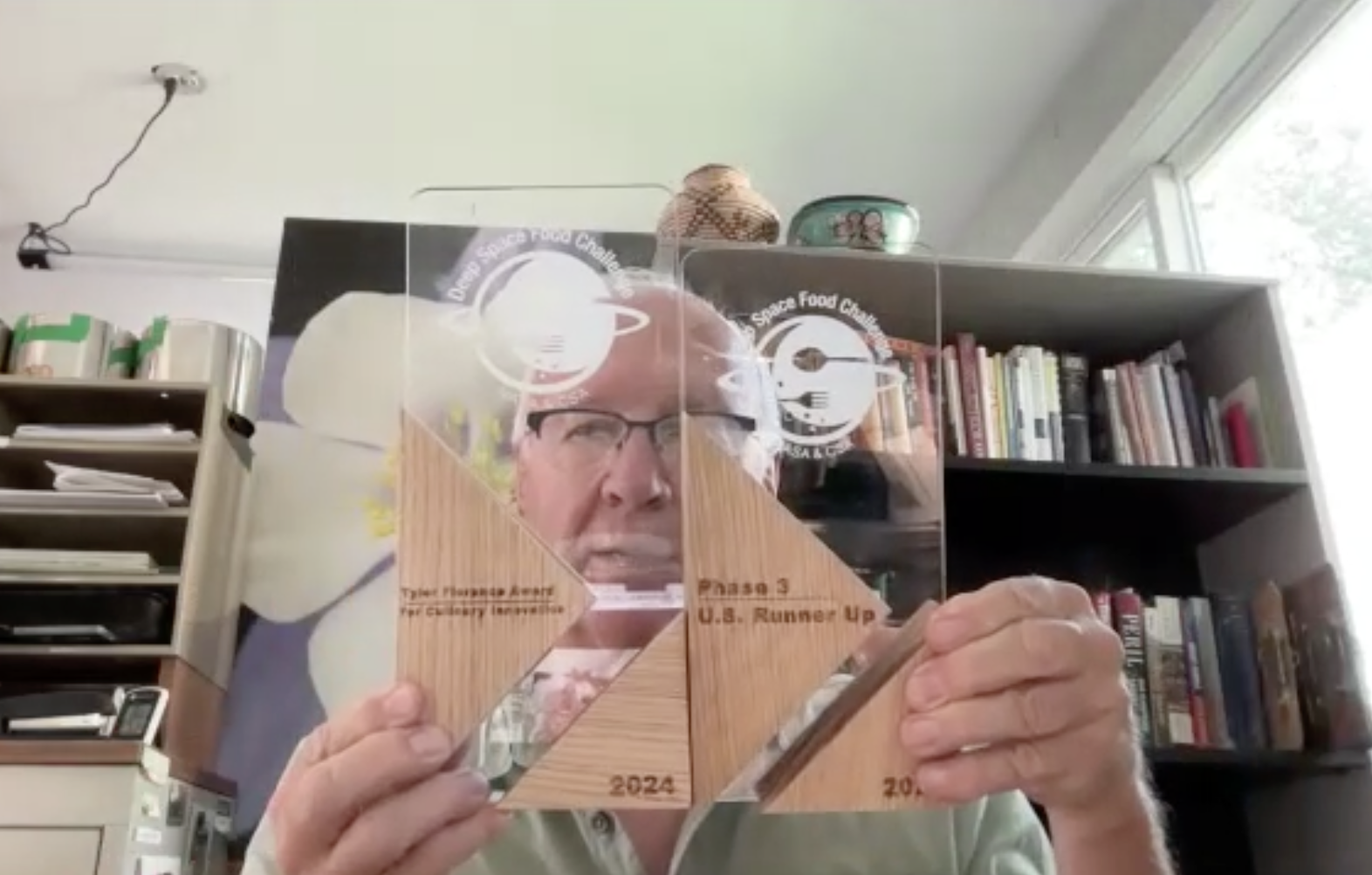

About a month later, in mid-August, Sears and his family flew back to Columbus to attend the symposium and awards ceremony. It was a whirlwind two days of networking with the commercial space industry, space pizza demonstrations and tasting, and attending and giving industry talks. It wasn’t until the last thirty minutes of the two days of programming that the winner was announced: It was Interstellar Labs, which develops advanced bioregenerative greenhouses. Sears and his SATED oven were named runner-up.

“I made peace with it right away, because this whole process has been a win for me,” Sears says. “I’ve just really had a huge amount of satisfaction and pleasure just from the process over the last few years of getting here. So this has been a great thing to do, and working with [NASA] and just doing everything to a T. It’s been great.”

Jim Sears holding his two awards.

Helen Xu

SATED was also the winner of the Tyler Florence Award for Culinary Innovation. When we chatted, Sears held up his two awards and said, “Here’s my runner-up award, here’s Tyler’s. And you know, Tyler’s is bigger and I actually appreciate it more because I mean, having an award for culinary innovation – that’s what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to make the best appliance possible, so I was delighted to get this.”

In fact, Sears is taking a SATED oven to Tyler Florence in San Francisco so the celebrity chef can experiment and develop space recipes. Sears will be doing the same with the José Andrés group, taking a SATED oven to senior director of research and development Charisse Grey, whom he met through the Deep Space Food Challenge.

“I’m Japanese, from Hawaii,’ Grey says in a Longer Tables blog post, “and I work with José, of course, so my mind immediately goes to rice, which means, if you have stock and freeze-dried vegetables and protein, you might be able to successfully make paella! … We’re really getting to understand the parameters of cooking in zero gravity, understanding what’s possible, and pushing culinary boundaries as a result. It’s food in the final frontier, and we’ve only just scratched the surface.”

Along with $250,000 in prize money, this type of exposure is exactly what Sears and SATED need. Getting runner-up or even winning the Deep Space Food Challenge comes with no guarantees or expedited path to the International Space Station. There’s continued work to make the technology space-compliant; as a next step, Sears is looking to get SATED on a zero-gravity flight so he can test out the process end to end, including ingredient injection, airborne particulate control and applying spices, all in a zero-gravity environment.

Then either NASA or the ISS National Laboratory has to approve the project with an estimated 18 to 24 months of engineering, manufacturing, certification and waiting in line before the SATED oven could make it onto the ISS. Additionally, the Johnson Space Center Food Lab, the ultimate gatekeepers of astronauts’ diets, would need to approve the SATED oven for regular use.

So Sears and SATED need a lot of attention, money and time to succeed, which is why Sears is looking forward to partnering with Florence and Andrés to develop recipes. Those partnerships can lead to grants and sponsorship money, educate politicians and government officials about his technology, and bring a broader awareness of the possibilities of cooking in space. The more space quiches, space pizzas and space cakes made and consumed on Earth, the higher the possibility that one day they’ll be consumed by astronauts, giving them a small taste of home while they’re in outer space.