My dentist hits the button and slowly brings the chair back to vertical.

"All right," he says. "We're done. How ya doing?"

I nod, say something about being okay, all good, splendid. "Really done?" I ask. "That was..." Gross. Annoying. Disturbing. Double-gross. "...not so bad."

He smiles, turns half away from me and starts cleaning up and rearranging his instruments. "Okay," he says. "Do you smoke?"

I admit that I do.

"Don't," he informs me. "Hold off as long as you can. No pointy foods. No nachos." He continues on. The list of don'ts is brief but fairly conclusive. No booze, no hot beverages, no cigarettes — my three-legged pyramid. I will collect some more don'ts off the computer later. No spitting. No coughing. No food that isn't mushy, soft pap — so, essentially, no food.

The gut stitches he's put in me are dissolvable; I have about six days to go before they disappear. I start my internal stopwatch. One hundred and forty-four hours. Eight thousand, six hundred and forty minutes. I shake his hand. In all seriousness, he's an awesome dentist. We've done a lot of work together — me and him and my dumb, soft, Irish teeth. He's never hurt me once. I trust him so much that I don't even whine for the Oxycodone scrip.

Still, I am a bad patient. I light up a cigarette as soon as I'm out of sight of his front door, my jaw packed with bloody, salty, wet gauze. I'd been in the chair for almost three hours — I need it. I tell myself that I'll just have the one, smoking carefully, then lay off.

I light my second about twenty minutes later, having held out as long as I could. In the car, I spit out the first wad of gauze. I can feel the ends of the stitches with my tongue, like little hairs. But I have to stop: No poking at the affected area with your tongue, that was another one of the rules. I put in a fresh plug of gauze and taste blood in the back of my throat. It makes me want a steak real bad.

At home, I ration the smokes. I drink a lot of water. I manage about 24 hours of my new diet of nothing by eating just ice cream, but by the next morning, I am beginning to lose my mind. I've dreamt about food like I haven't since I was working for a living, back when I was poor and had only visions of sashimi and baklava to sustain me. For breakfast, I have water, then green tea, boiled, steeped and left to cool until it is the temperature of the blood that still seeps from the wound in my mouth that I can't stop tonguing. I want a cheeseburger. I would steal for a plate of corned beef hash and murder for a breakfast burrito. Already, I am difficult to be around because (I am told) I keep looking at people as though I'm ready to take a bite out of them, like I am mentally breaking them down into chops and loins and ribs.

It is at about the 36-hour mark that Laura comes up with the first suggestion that doesn't make me want to hit something: soup. How could soup possibly hurt you? she asks.

"Nothing hot," I tell her. "No noodles. Nothing that requires chewing. Nothing that's going to get stuck in an open wound."

But still, I'm thinking...

Forty-eight hours. Sixty. Desperate, sneaking a pierogi from the kitchen, something goes wrong. I can feel one of the stitches pop loose, a lump of puckered skin move. I panic. I don't believe in God, but I start talking to somebody — bargaining, threatening, saying, "Just let this be okay. I'll be good. Nothing but mashed potatoes and water. It's been (check watch) sixty hours and twelve minutes. Maybe I'm healed." I've known mouth pain before. Abscessed tooth, broken teeth. I've had my jaw broken (once) and dislocated (twice), and never got it properly fixed. I know from pain and know to fear it like wrath, like vengeance. I am terrified for about a half-hour, expecting the rush of lightning in my jaw, tensed up for it. Then, for another hour, I am wary. The pain doesn't come. After that, because I'm stupid, I feel impervious. Immortal.

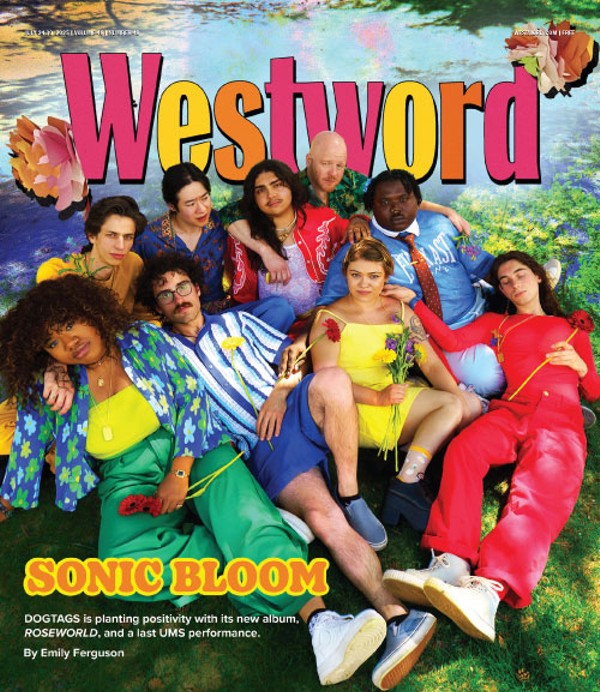

Soup. The next day, I head to a strip mall on West Alameda, home to some of my favorite places on earth. It is old, ugly, battered and rattletrap — and I love it. I want to live here. I want to pitch a tent on the asphalt and eat shumai and cha sui bao three meals a day. And pho. Lots of pho.

Inside Pho 99, there are more fish than people — fish in tanks by the door, on the counter, by the register. This is a simple space — comfortable and open and bright, friendly but not much more than functional. People come to Pho 99 to eat, nothing more. Which is fine, because eating is exactly what's on my mind. Pretty much the only thing on my mind.

The pho tai gan comes with a jungle tangle of greenery on the side — limes and jalapeños, mint on the stem and purple basil that I can smell even before I fold the leaves and tear them, bean sprouts (yuck) and Vietnamese sawleaf herb. Inside the big bowl are noodles (of course) and green onion (of course), white onions sliced razor-thin, sliced beef and tendon. I swallow most things whole, like a snake, and chew the rest carefully. The broth isn't sweet like some of the broths you find at other pho places; it doesn't have the cloying lick of cinnamon and star anise that some of those places offer instead of a more honest and savory complexity. This is working-class pho — plain, straightforward, serious. And it's salty with beef juice because the meats are done in the traditional way — added raw, cooked by the heat of the scalding broth like Vietnamese robata. I don't think I've ever finished an entire bowl of pho before.

And then I order more: pho ga nac, essentially chicken noodle soup. This broth is lighter, brighter, with almost a vegetable note. It does not have the bloody sincerity of the beef, but it makes for an excellent dessert.

I feel good when I'm done. I feel fed. More important, I feel no pain. I walk out probing the healing gash in my gum with the tip of my tongue, counting the puckered holes, the little rat-tail ends of the stitches that are still there. I am halfway to better, seventy-odd hours in.

And the next day, I'm right back at Pho 99. The staff (all two of them) are watching TV behind the counter, and they wave me into a seat at a small table set with disposable chopsticks, pho spoons, a napkin dispenser and six kinds of condiments. I take a menu. I know I can't eat rice, which kills the com dia and com tam side of the menu (including the simple, perfect broken rice with lemongrass chicken that I've had before, as well as the fried rice with shrimp, grilled pork and Chinese sausage), and should probably avoid the appetizers, too (egg rolls are too crunchy, spring rolls too chewy, grilled sausage in rice paper too...sausagey). I flip to the back page. Pickled plum soda. Soda with egg yolk and condensed milk (which is not quite as nasty as it sounds). Soybean milk. Must be tough to find the nipples on those little beans, I think.

I flip back to the appetizers, and when the waiter comes to my table, I order chao tom anyway: shrimp paste, molded into a patty, seared and sliced and served with vegetables, peanut sauce, noodles and dry rice paper rounds that have to be soaked for a DIY spring roll. I order bun bo Hue — Hue-style noodle soup with fat, snaky udon-like rice noodles, pork hock, steamed pork, chewy tendon and a big, lumpy knuckle of fatty meat, a beef shank, floating at the bottom for flavor. And even though I've been off coffee for six months (another doctor's orders, diligently obeyed until now), I order a Vietnamese coffee, iced, heavy on the sweetened condensed milk. This is all wrong. This could be very bad for me. But I hate being told what I can't do. And if I'm going to pay for this meal later, I might as well go down fat and happy. I might as well enjoy myself first to temper the possibility of later suffering.

The chao tom is excellent, squishy under my good teeth and flavored like the packet of magic powder that comes with ramen soup. I make four rolls out of it, all ugly and lumpy things, but functional, like Pho 99's dining room. The bun bo Hue is an acquired taste, but one that I acquired long ago — the broth greasy with fat and reddish with tomato and chile. My beef shank still has whiskery hairs on it, which I appreciate: They show that this is the real thing. The soup is served with a kind of Asian salsa of chopped herbs, greens and dried onions that cuts the heaviness of the broth with a vegetable cleanness. I spend 45 minutes shoveling soup and shrimp paste into my smile, drinking coffee sweet as a kiss, thick as honey, until I feel jittery and lightheaded.

I am a terrible patient and a stupid, stupid man. I get that. I can't do right even when it's in my own best interest, even when doing right means good health, the abeyance of pain, bland and boring safety. Doing wrong is just too much fun — occasionally delicious, never dull. Doing wrong has gotten me a lot of places, has worked out well for me so far. And as I stand to pay the ridiculously small bill for my ridiculously large meal, I make another deal with whoever's listening: Let me get through this and, starting right now, I will be good. I will follow doctor's orders. I will be on my best behavior.

Right outside the door, I light a cigarette.

Okay, starting tonight I will be good. I promise.