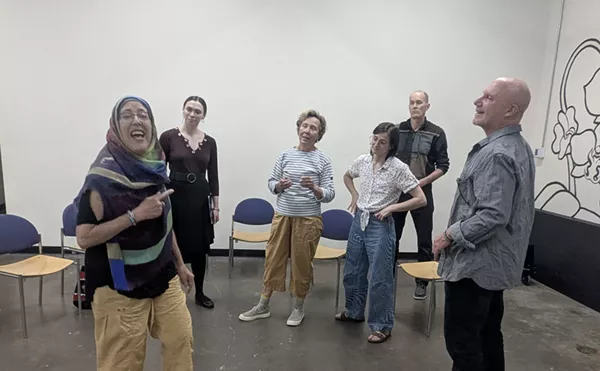

Suddenly, one of the camp's officers, who's playing the merchant who's indebted to Shylock, rises from the audience and steps uninvited into the scene. As the prisoner reaches the end of Shylock's moving speech, he locks eyes with his imposing adversary. Then, to the eerie accompaniment of real-life train whistles echoing outside the LIDA Project's garage-turned-theater, the doomed man pointedly asks the commandant, "If you wrong us, shall we not revenge?"

That's just one of several chilling moments in The Merchant of Auschwitz, director Brian Freeland's engrossing adaptation of the Bard's problematic comedy. Poignant though it is, however, Shylock's bitter rant is also one of the few scenes in which Shakespeare's crackling dialogue can be both heard and understood: Several of the performers employ obtrusive, thick German accents or rush their lines in the heat of battle. But while audience members unfamiliar with Shakespeare's original might initially find Freeland's approach difficult to follow, the ninety-minute intermission-less show gradually proves a riveting, unforgettable version of a play better known for its anti-Semitic overtones than for its theme about outward appearance and inner beauty.

In fact, from the moment theatergoers enter the intimate performance space, they're reminded of the play's anti-Semitic aspects. After being greeted at the box office by a German-speaking woman sporting a white blouse, black skirt and buzz cut, spectators are compelled to make a discomforting decision: Should they sit in padded black-and-red chairs located underneath a large Nazi flag or take a seat on one of the rough-hewn pine bunks that line two of the theater's other walls? (Scene designer Jason Humphry's innovative, haunting set so deliberately blurs the boundaries between performance and audience that even a trip to the restroom means walking just inches away from a bleak alcove where the prisoner-actors are milling about.)

Following an announcement by the friendly box-office fraulein, several bare lightbulbs hanging from the rafters slowly dim and we're introduced to Antonio (Josh Hartwell), a Venetian merchant in desperate need of money. Moved by his friend's melancholy, the dashing Bassanio (Jim Miller) solicits Shylock (Nils Ivan Swanson) for a loan of some 3,000 ducats. But instead of merely importuning the wealthy Jew for cash, Bassanio, Antonio and a few Nazi henchmen kick, punch and spit on Shylock until, lying in a heap on the floor with his fingers outstretched toward Antonio's withdrawn boot, he agrees to loan them the money--on one condition: If the debt isn't satisfied by an agreed-upon time, Shylock is entitled to remove from Antonio a "pound of flesh" (which the Jew interprets as his foe's still-beating heart) as payment.

We're quickly transported to Belmont (scene changes are indicated by a prisoner who walks about with makeshift titles scrawled on placards), where Bassanio's beloved, Portia (Tara M.E. Thompson), lives. Speaking in a slow Southern drawl, the blond bombshell interviews a couple of supposedly loquacious lovers portrayed by a single tortured young woman (Sara Casperson) who's barely able to speak her lines. Her reticence--abetted by Portia's flirting--only exacerbates the Nazis' ire. A few scenes later, Shylock's daughter, Jessica (Lisa Mumpton), is forced to betray her father by donning a swastika armband, and the prisoners' collective despair soon reaches its nadir: Jessica is viciously assaulted by her boyfriend, Lorenzo (Paul Cure), and his SS thugs moments before Shylock gets his comeuppance in the play's famous trial scene.

Throughout the gripping drama, Freeland orchestrates several intriguing juxtapositions of action and dialogue, beginning with the antics of a street clown, Launcelot (Steven Brown), whose hand-puppet routines take on new meaning when performed against the backdrop of a concentration-camp setting. Similarly, as Bassanio explains his dicey financial predicament to Portia, Miller extends one arm in the direction of the prisoners' alcove and the other toward the seated Nazis (including Antonio), saying he has "engag'd my friend to his mere enemy/To feed my means." It's a marvelously staged episode that, much like Shylock's discovery that his "own flesh and blood" has forsaken him, beautifully weaves together the production's many fragments--fiction and history, oppression and rebellion, false face and immutable reality--into a whole that's overwhelmingly greater than the sum of its parts.

But even though he's mostly faithful to Shakespeare's story, some of Freeland's choices seem ill-advised. His decision to change Jessica and Lorenzo's post-trial "love scene"--which Shakespeare used to give the play a happy ending--into the pre-trial assault may not have been necessary, considering his already radical reinterpretation of the play. In fact, the scene, left at the end as originally written, might serve as a postscript to Shylock's extreme punishment, adding another layer of commentary when Jessica falls in love with the same Nazi who helped brutalize her father. And, given that the show is apparently being performed for a German audience, it seems incongruous--and makes it hard to understand the dialogue--when the actors maintain foreign accents even though they are, in effect, speaking their own language. Freeland may have been attempting to implicate Americans by making his characters strain to speak our language, but rendering Portia (she of the "quality of mercy is not strained" speech) as an ugly, crass American broadcasts enough of a message about our country's political shortcomings, both past and present.

Even so, Freeland's effort--well-acted by his splendid ensemble cast of performers--is eminently worth seeing, if for no other reason than that the talented director is virtually the only person around with the skill, intelligence and guts to turn his radical vision into a convincing, shattering reality. The production's few rough edges are simply part and parcel of a rugged theatrical landscape that most other directors, fixed in rigid routine, are reluctant to artfully explore.

The Merchant of Auschwitz, through May 30 at the LIDA Project Experimental Theatre, 80 South Cherokee Street, 303-282-0466.