"We've been at one phase of a drought or another over the past seventeen or eighteen years," notes Bart Miller of Boulder-based Western Resource Advocates. "And many scientists say we're at a new normal as far as snowpack and drought conditions [go]."

As the director of the Healthy Rivers program for WRA, Miller stresses that fire danger is only one side effect of water shortages in Colorado — a reality exemplified by the early peak of the Colorado River this season.

"Some of the related impacts of when rivers reach their peak are things like low flows and temperature in the water," he points out. "Low flows usually mean higher temperatures, and that means more stress on fish. Anglers are concerned about what things like that will mean at the end of the summer, when the flows are even lower. And low flows also make it harder for communities to meet their water-quality requirements. If you're discharging water from a water treatment plant, high flows are good, because they dilute what's coming out of these facilities. And, of course, higher temperatures and drier soils mean a much more increased chance of fire danger."

For most communities, Miller acknowledges, "a drier year is not that big of a deal. Many communities have ground water and water storage that can make up for it." But that's not the situation in which Colorado and much of the West currently finds itself, as indicated by what's going on at Lake Powell, which Miller describes as "a storage bucket for the upper Colorado River basin." As of this week, the Lake Powell Water Database notes that the water level is down 13.69 feet from this time a year ago and is just 53.26 percent of what's known as "full pool."

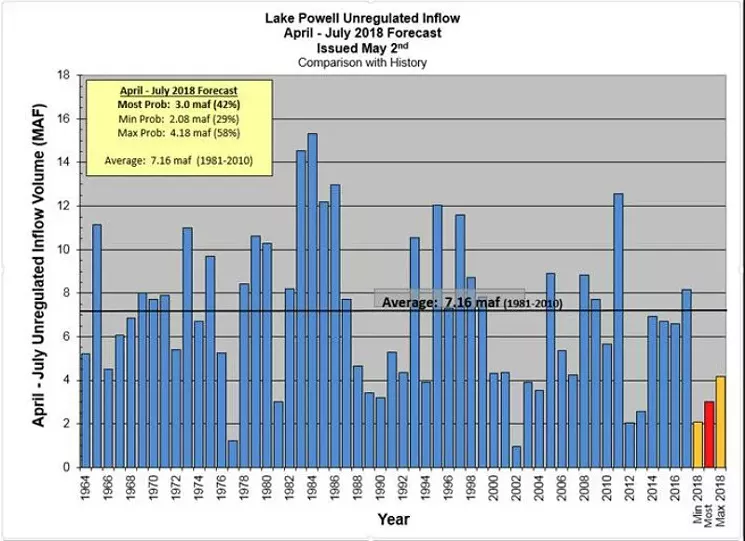

Such scenarios have been all too common in recent decades. The following graphic shows that water levels at Lake Powell have been below average in twelve of the past twenty years.

According to this graphic, the unregulated inflow volume at Lake Powell has been below average for twelve of the past twenty years.

According to Miller, such figures are even more dire than they seem at first blush.

"When people look at flows or snowpack as compared to average, they usually use the most recent thirty-year average," he says. "But because the last seventeen or eighteen years or so have mostly been below average, that thirty-year average has dropped. What used to be average is now a lower marker, so the point of measurement is even lower. Something that's 90 percent of average now used to be 80 or 85 percent of average."

Such developments haven't escaped the notice of analysts at the state level, as evidenced by the Colorado Water Plan, released in 2015 and accessible below. The report "set out some objectives or metrics on where the state should head on water," Miller allows. "But one of the critical things we're dealing with now is how to fund that plan."

The amount of money needed is enormous — an estimated $20 billion for water supply, water infrastructure, recreation and the environment over the next thirty years. Fortunately, though, the funds aren't required in one lump sum, and they will be supplied by a multiplicity of sources.

"What's clear is that a big part of the plan is already going to happen," Miller emphasizes. "For large cities that have the need for additional water, they have programs and projects that are pretty much funded; they have the means to do this. But there's a subset of elements in the water plan that really don't have funding, and that goes back to stream health across the state. There hasn't historically been much funding to secure stream health, so in the two and a half years since the plan came out, river-basin groups and stakeholder groups have been meeting to talk about what their watershed groups need: how to deal with temperatures in certain places or how to deal with the flow. Farmers and ranchers have been at the table, too, and they've helped come up with game plans about what we need to do. But coming up with a list of projects is the first step. Having the resources to do those things over the years is the next one."

A smoke plume from the 416 fire as seen from the Hermosa Creek Campground.

National Wildfire Coordinating Group via Inciweb

Money has started trickling in, Miller stresses: "From the middle of 2017 to the middle of 2018, the state's water conservation board has put almost $25 million toward implementing the plan. But because the board's funding comes down through severance taxes on oil and gas, the amount varies as to how much of that activity is happening, and the projections for the taxes have been coming in very low — they've been bouncing around zero. So it's a variable and unreliable source of funding, and one chapter of the water plan talks about the need for a different funding source that would be reliable over the long term. There are discussions going on now to figure that out — not just for the next year or two, but also to look at what kind of other revenues might be available."

Another risk: Cash for improving stream health could be de-prioritized in favor of funds to fight conflagrations like the 416 Fire, which has grown to such a degree that Governor John Hickenlooper, senators Michael Bennet and Cory Gardner and Representative Scott Tipton will visit the Durango area on Friday, June 15, for an update on the battle. But in Miller's view, anything that can be done to address current water issues is a positive.

"Water is the most essential element in Colorado," he says. "It's important that we figure out how to secure our future, and that means putting resources toward it: money, people and energy."

Click to read the 2015 Colorado Water Plan.