Escuela Tlatelolco was born out of the Chicano civil-rights movement. Gonzales, who grew up in the barrios of Denver and attended Manual High School, originally pursued a career in boxing, and at one point was ranked among the top three featherweight fighters in the world by The Ring magazine. But over the years, his passion shifted toward activism and the arts (his 1969 poem “I Am Joaquin” served as a rallying cry for the Chicano movement.). He became the chair of the Denver-based Crusade for Justice, which fought for Mexican-American political, social and economic rights, then in 1971 started Escuela Tlatelolco at 1571 Downing Street, right by Crusade headquarters.

Tlatelolco was a center for arts and education in the Aztec Empire, as well as a plaza in Mexico City where hundreds of student demonstrators were massacred by the government in 1968; Escuela Tlatelolco seemed the perfect name for a school whose mission was guaranteeing a quality education for Latino students while specifically incorporating into the curriculum a focus on cultural heritage and social justice.

"The school had a profound mission: to provide quality education with an emphasis on cultural identity and social responsibility," says Jesse Ogas, who has served on Escuela's board of trustees for thirteen years. "It taught students to learn about their ancestors and culture, and why to be proud of that."

The school quickly gained national prominence, drawing benefactors from all over the country and eventually growing to offer K-12 instruction. It was doing well enough that in 1995, it bought its current home at 2949 Federal Boulevard from St. Dominic's for $610,000. But running Escuela Tlatelolco there proved challenging, and in 2004 the board decided to contract with Denver Public Schools. "At the time, we thought it would be a great partnership," says Ogas. Many loyal and longtime donors disagreed, however; they viewed the deal as selling out and withdrew their support.

Then in 2014, after Tlatelolco failed to meet district performance standards for multiple years, the DPS and the school came to a mutual agreement to end the contract at the end of the 2015-16 school year.

Many at Escuela Tlatelolco view DPS's assessment of the school's performance as unfair. "When you are taking children who flunked out of other DPS schools and are reading at a third-grade level in eighth grade, you don't teach them overnight," says Ogas. Camila Lara, the current chair of the board, is actually an Escuela alumna. "The school means a lot to me," she says. "I had a lot of challenges with public high school, and probably wouldn't have ever finished. The Escuela was kind of my savior."

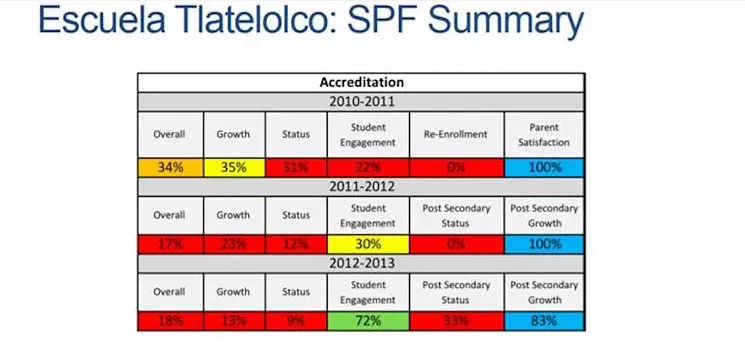

A graphic of Escuela Tlatelolco's SPF Summary given to the school board in Novemeber 2013, the year before the contract ended.

Denver Public Schools

But Alex Renteria, a spokesman for DPS, points to the school's consistently dismal scores in the district's yearly School Performance Framework in student achievement and lack of progress over time. (The only standard that Escuela Tlatelolco consistently met or exceeded was parent engagement and satisfaction.) "We hold ourselves and our schools to a high standard," says Renteria.

Ogas and Lara believe there are other, more significant measures by which the success of the school should be judged. "Since its inception, we've graduated more than 7,000 people," Ogas says. "Of those, 72 percent go on to post-secondary education, and many receive their bachelor's, master's and even doctoral degrees."

After the loss of so many benefactors, losing the district's funding as well was a hard blow. Escuela Tlatelolco had a large deficit at the end of the 2016-17 school year, and the board decided there was no way for the organization behind the school to recover unless the school building was sold. The 21,000-square-foot structure is located in what is today prime Highland real estate, and the board has put it on the market for $3.95 million.

On July 1, Escuela Tlatelolco officially announced its closure. Last year, the school served 145 students between kindergarten and twelfth grade; the school's principal, Nita Gonzales, and the board are now working with families to help transition those students to other DPS schools for the fall. Nita is the daughter of Corky Gonzales, who passed away in 2005.

The Denver Public Library branch at 1498 Irving Street is named for the late activist — but his legacy reaches far beyond that. The news of the school's closure was emotional not just for Coloradans, but for Chicano and Latino activist groups across the Southwest that viewed Escuela Tlatelolco as a bastion of the Chicano movement. "The announcement caught a lot of people by surprise," says Debra J.T. Padilla, who runs the Los Angeles-based SPARC (Social and Public Art Resource Center), a nonprofit started by Chicana artist and activist Judy Baca. "There are not many agencies that serve as a beacon for history like the Escuela did."

Both Padilla and Ogas say they're optimistic about the future of Escuela Tlatelolco. "Though it’s heartbreaking, it’s also a time for reflection to look at the next chapter of Escuela Tlatelolco," says Ogas. "Our next steps will be to 1) sell the building, 2) settle our financial obligations and 3) take a deep breath and look toward what the future holds."

Ogas is confident that the ideals Escuela Tlatelolco stood for will continue to exist, in some shape or form. The board has already been in discussions about possibly merging with local Latino organization Servicios de la Raza, becoming a charter school, or even transitioning to a college scholarship fund.

"We are focusing on sustainability," says Lara, "but the outcome may not be the same as it was." Over its 46-year history, she points out, Escuela Tlatelolco went through many changes. Whatever happens next, she is sure the organization will continue to meet the needs of the community it set out to serve.

Tony Garcia, executive artistic director at El Centro Su Teatro, voiced hope for Escuela Tlatelolco in an epilogue he wrote for the school: "One thing our community is good at is rising from the ashes," he said. "I have no doubt that we...will adapt and be revived. We will create a new home for our children and our community."