Glenn Cuerden

Audio By Carbonatix

For a man concerned with gravity, Dave YÅ«st carries himself light as a feather, floating through his exhibit at the Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art like a water glider, moving from one painting to the next with an explanation for each detail.

The lines applied in his paintings contrast directly with the excited, erratic trajectory of the artist’s oeuvre. They are catenary curves – the form that a chain, string or cable assumes when supported on two ends under its own weight. Not exactly parabola, as Galileo once examined, but close to it – similar to a telephone wire or a jumping rope. They’ve been YÅ«st’s focus for 23 years, as seen in his Inclusion series, which is on display along with a retrospective collection of his paintings and prints at the Kirkland through October 1.

Born in 1939 in Wichita, YÅ«st studied aeronautical engineering and architecture at Wichita State University and Kansas State University before realizing that he wanted to pursue art full-time. He was introduced to painting at age twelve, when he spent a summer studying art with a family friend, the renowned Swedish pointillist Birger Sandzén. (The Sandzén Memorial Gallery also loaned works for the Kirkland’s current exhibition, supplementing the museum’s permanent collection of YÅ«st pieces.)

YÅ«st earned a BFA from the University of Kansas in 1963, shortly followed by an MFA from the University of Oregon in 1969. During his graduate studies, he began to teach in the art department at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, where he and his studio currently reside, and continued his tenure for 47 years before leaving the position in 2012.

Will you step up to support Westword this year?

At Westword, we’re small and scrappy — and we make the most of every dollar from our supporters. Right now, we’re $23,000 away from reaching our December 31 goal of $50,000. If you’ve ever learned something new, stayed informed, or felt more connected because of Westword, now’s the time to give back.

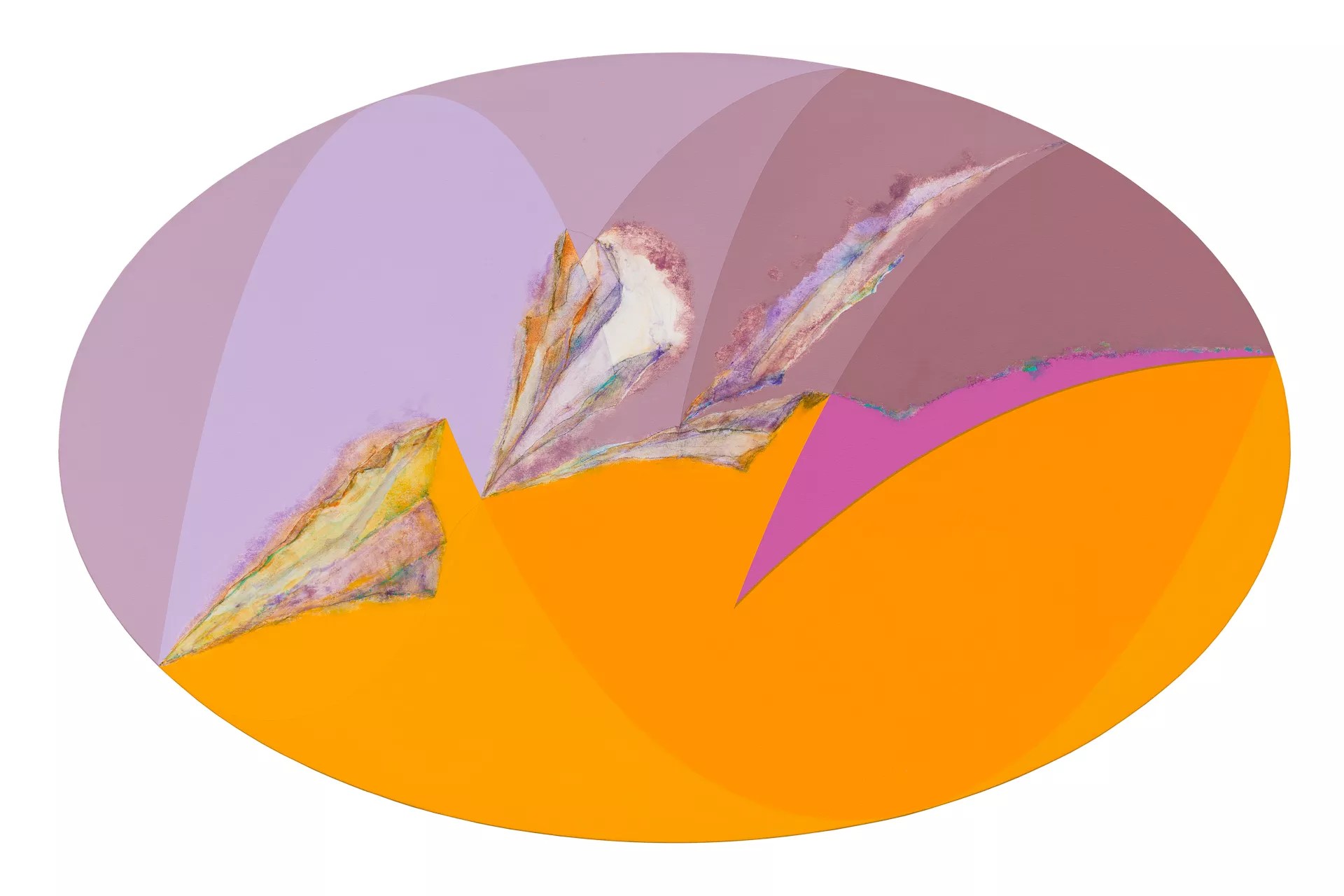

One of Yūst’s elliptical paintings, “Chromaxiologic Inclusion w/ 5 Catenary curves # 6/17.”

The Kirkland

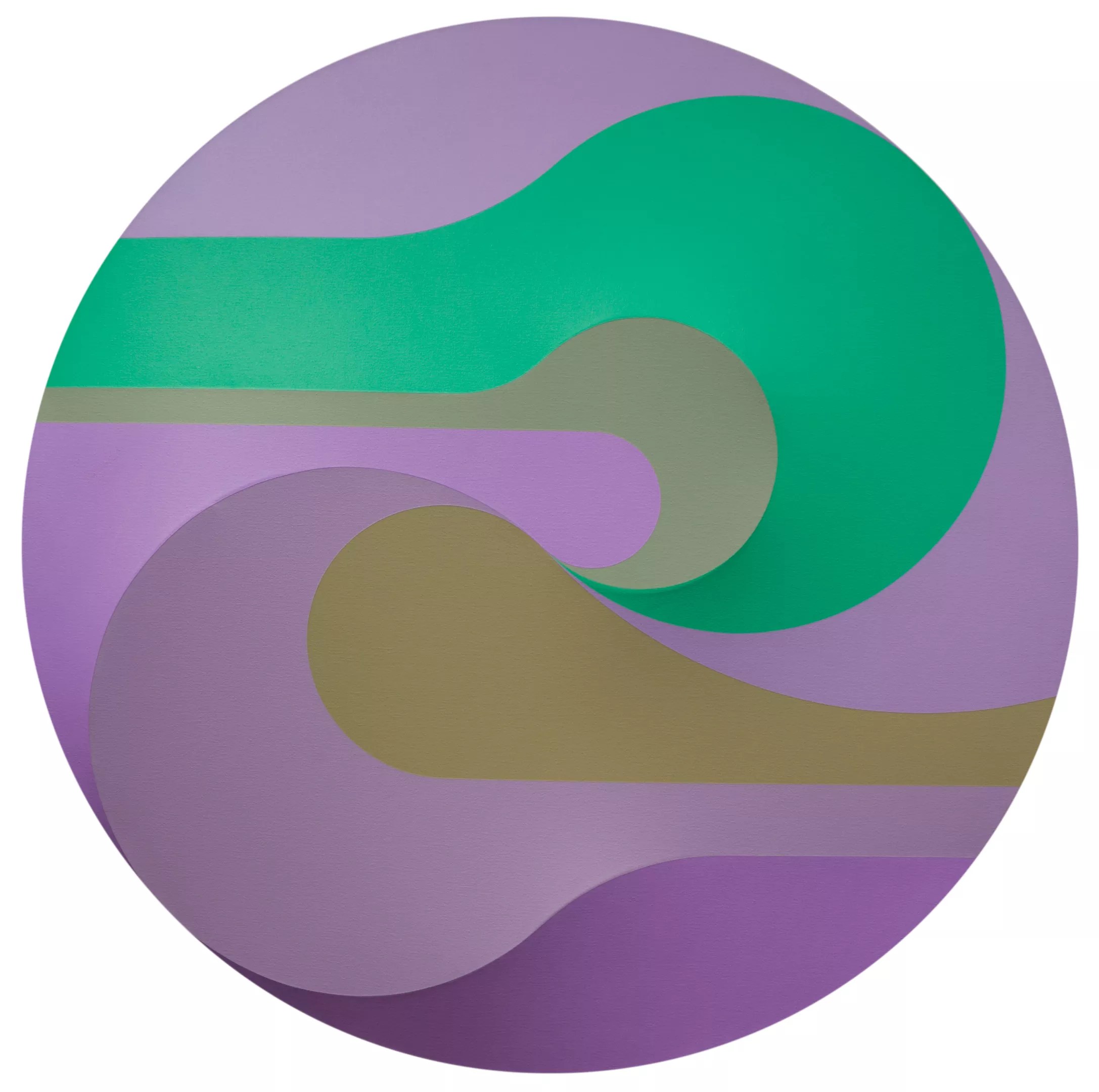

The Kirkland exhibition, Evidence of Gravity and Other Works, was co-curated by the museum’s founding director, Hugh Grant, and deputy curator Christopher Herron. YÅ«st’s earlier work, displayed in a retrospective containing seven compositions from 1967 to 1988, is characterized by an interest in shape and symmetry that grew from graduate school. In his studies, YÅ«st says, bilateral symmetry was something to be avoided, so he went with something different, skating around the rules. Shapes are scaled, reflected, rotated and translated across circular canvases until they are to YÅ«st’s taste, almost as if he were solving an equation.

The artist is “trying to search for an interesting solution to this mix of geometry and biomorphic shapes,” he explains. “It is this dichotomy of trying to resolve organic shapes along with geometry that has been an underlying theme of my painting since the late ’50s.”

Indeed, equations take on a large role in YÅ«st’s process. His sketchbooks contain line after line of algebra in search of angles, curvatures and points along a vector, demonstrating the precision with which he approaches his work. His earlier compositions are done on rectangular canvases, where he developed the biomorphic abstractions seen in the circular and, from 2006 to 2019, elliptical canvases of his later years.

The impressive architecture behind the canvas is an often unrecognized feat of YÅ«st’s compositions. Since moving toward circular and elliptical canvases, he has designed and perfected his own technique, founded on his history of building model airplanes, to create three-dimensional canvases, stretched across an intricate construction of hundreds of pieces of uniquely measured, cut and glued plywood. The Kirkland ensures that ingenuity is not ignored, carving out space behind the wall of “Circular Composition #60” to highlight the artist’s structure.

“I had an exhibition in 1975 at the Denver Art Museum, and there were a number of three-dimensional paintings,” YÅ«st recalls, “and someone who oversaw the gallery space told me that people would come in and bomb through the whole gallery until they came upon one painting that I had, suspended in front of a piece of plexiglass mirror, where they could see the backside reflected. And once they saw that, they would go back through the whole exhibition again, really slowly, processing what they saw in the reflection.”

“Circular Composition #60” is displayed in the museum with the back canvas stretcher viewable.

The Kirkland

YÅ«st’s exposure to Spanish architect Antonin Gaudí’s use of catenary arches during a visit to Europe in 2000 sparked his interest in the technique. The only force acting upon the curve is gravity, hence the exhibition’s name. Unlike the curves of his earlier works, which were based on the curve of a circle, YÅ«st achieves catenary curves by hanging metal ball chains (which work far better than string, he says) in front of the canvas.

The design of each painting, of course, starts much earlier, as seen in one of YÅ«st’s sketchbooks displayed at the entrance to the portion of the gallery with his recent works. A sketch may be reiterated dozens of times before assuming the proper synthesis of geometric and biomorphic shapes central to YÅ«st’s recent style.

He terms his experiments with color “chromaxiologic” – “chroma” meaning color and “axiology” referring to “color value judgments.” In line with the geometric-biomorphic design, Yust’s works combine solid swaths, often in a broken gradient between several catenaries, with striking watercolors interrupting the strict geometry, reminiscent of natural landscapes. The paint is applied horizontally, similar to the technique of abstract painter Vance Kirkland, the museum’s namesake.

“CATENARY CURVE Inclusion #1,” Yūst’s first painting made with catenary curves.

The Kirkland

Another word that has taken on a pronounced significance for YÅ«st is “inclusion.” It became the title of his most recent series after he took to heart a quote by architect Robert Venturi, referring to architecture, that reads, “It must embody the difficult unity of inclusion rather than the easy unity of exclusion. More is not less.” This idea took on meaning for Yüst in his painting.

“Before I read that article,” he says, “I don’t think any of my paintings had any more than five or six colors, and I thought, ‘I need to find a different way of dealing with these other things, including rather than getting a resolution by simplification and exclusion.'”

How does he know when he is done? “You could ask: ‘How do you know you’re in love?'” responds YÅ«st. “I’m not sure I know the answer. Somehow things begin to fall together. Another way I could talk about it would be to say I try to paint myself out of the painting. When I get to the point where I can’t think of anything else to do, and I’ve not just made it different, I’ve made it better, then I know.”

YÅ«st will be giving a talk at the Kirkland on Wednesday, September 13, to speak more about his process and history as one of the most prominent artists in Colorado. His exhibition will run alongside the Kirkland’s permanent collection until October 1, after which they will join the other fifteen canvases that YÅ«st has stretched in his studio – perhaps evidence themselves of more to come.

Evidence of Gravity and Other Works is open through October 1; An Evening With Dave YÅ«st, 6 to 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, September 13. Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art, 1201 Bannock Street, kirklandmuseum.org.