Michael Roberts

Audio By Carbonatix

For nearly five years, Denver has waited to try out a new method to prevent drug overdoses in the city – offering designated spaces for people to use illegal substances under the supervision of medical professionals.

That wait will continue (indefinitely), as the legislative fight for these “overdose prevention centers” suffered a major blow on Monday.

The state’s Interim Opioid Committee rejected a proposed bill to allow a center in the Mile High City. Legislators voted down a similar bill in April, but proponents and opponents joined forces to draft this new version. Representative Chris deGruy Kennedy, the bill’s sponsor, says he was “very close” to getting enough support to pass it through the committee, but Governor Jared Polis threw a wrench into his plans by telling legislators he would veto the bill if it ever made it to his desk.

“This was the one path that I saw that was going to get the job done,” deGruy Kennedy says. “Given the governor’s very clear words, if this version of the bill is not going to get his signature, there’s not another version of the bill that is.”

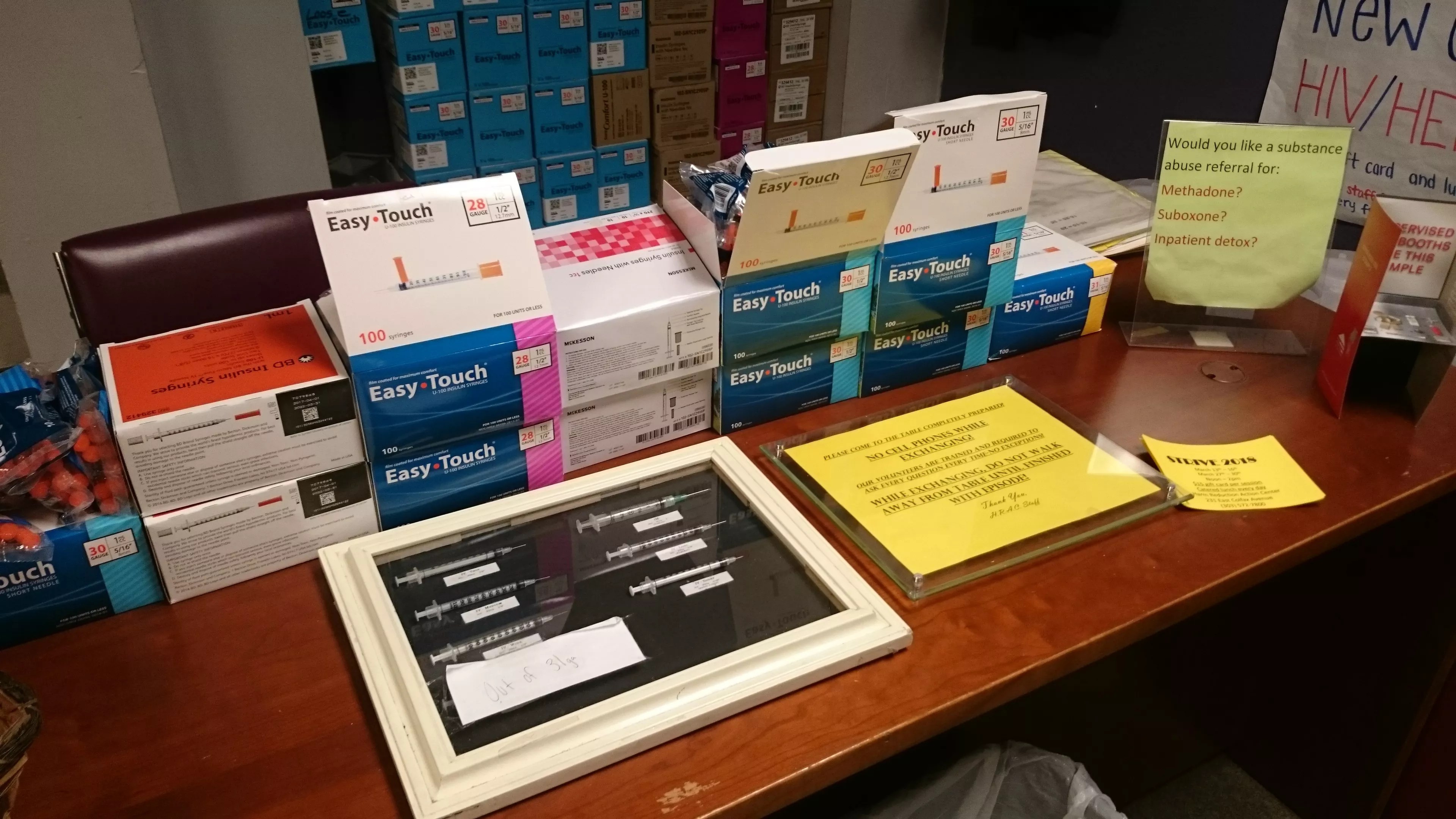

Advocates call overdose prevention centers a realistic approach to drug addiction, keeping users as safe as possible until they’re ready to quit. In addition to emergency medical care, they would offer sterile drug equipment and connections to counseling and other treatments.

Nearly 200 overdose prevention centers currently operate in fourteen countries, including two in New York City. No overdose deaths have been reported in any of them, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Still, critics view the centers as hurting surrounding communities and enabling drug abuse.

While experts testifying to the legislature said there is no evidence showing that the centers cause crime in surrounding areas, there is also nothing to suggest that they increase the likelihood of drug users seeking treatment. Because of this, opponents argue that money for overdose prevention centers would be better spent on treatment and programs intended to stop drug use, not just mitigate the dangers.

“Governor Polis has been clear with Coloradans and the legislature that he is opposed to these drug use sites,” says Conor Cahill, a Polis spokesperson. “He looks forward to continuing to work with the legislature to get people help for substance use disorders, end the scourge of fentanyl, and crack down on drug dealers.”

Denver City Council passed an ordinance authorizing the creation of an overdose prevention site back in 2018, but it can’t open the center unless state law changes to allow municipalities to do so.

That change looks unlikely now.

Individual legislators could always reintroduce the failed bill during next year’s legislative session, but deGruy Kennedy says he has no intention of doing so, as it ultimately needs the governor’s approval to become law – and Polis isn’t budging.

“It’s not going to happen within the immediate near term,” says deGruy Kennedy. “If I wasn’t able to win over the governor with all of the research I shared this summer, I’m not sure exactly what’s going to change his mind. … My assessment is that, for the governor, this was more about politics than anything. And I don’t know that that’s going to change in the next three years.”

Legislators voted 4-6 against the overdose prevention bill on Monday, with two Democrats joining the committee’s four Republicans in opposition. Senator Kyle Mullica was one of the deciding Democratic “no” votes both Monday and in April, when his Senate committee killed the bill after it passed the House.

Mullica has repeatedly raised concerns about whether prevention centers would be able to help the most people possible with the amount of resources they’d require. He worked with deGruy Kennedy on many amendments to the newest bill, including limiting it to only permit a center in Denver instead of all Colorado cities, but he was still worried about how to address any potential negative impacts the center could have on the surrounding community.

“You couple those concerns with the fact that other leaders had concerns, and it just wasn’t at a place where I could support it,” Mullica says. “That’s our job when the governor chimes in and says something: We listen and work with him. But it wasn’t just the governor who had concerns.”

Representative Mary Young – the only other Democrat to vote against the bill on Monday – said during the meeting that she supports overdose prevention centers but voted “no” because of pushback from her constituents. Mullica says he heard objections from constituents, community leaders and Denver Mayor Mike Johnston.

A Johnston spokesperson tells Westword that the mayor “does not believe that supervised injection sites are the right step for Denver in this moment” and is “focused on expanding access to substance misuse services to help Denverites get back on their feet.”

There’s a lot of work to do to get there: Last year, 1,799 people died from an overdose in Colorado, including 453 people in Denver, according to state data. Colorado had 1,881 fatal overdoses in 2021 – a record high for the state and nearly double the number of overdose deaths just three years prior.

As she faces these issues firsthand, Harm Reduction Action Center Executive Director Lisa Raville says she is “incredibly disappointed” in the bill’s failure. HRAC offers drug users sterile needles, fentanyl testing strips, free Narcan and referrals into recovery, and harm reduction organizations throughout the state have fought for the ability to become overdose prevention centers.

“They will never treat or incarcerate their way out of an unregulated and toxic drug supply. Ever,” Raville says. “People are dying, and dying publicly, and the governor knows it. It doesn’t have to be like this.”